Title IX

-

Title IX changed the rules for women

-

Was the merger of the AIAW into the male-dominated NCAA worth it? 1970’s

-

The History of Title IX 1980s

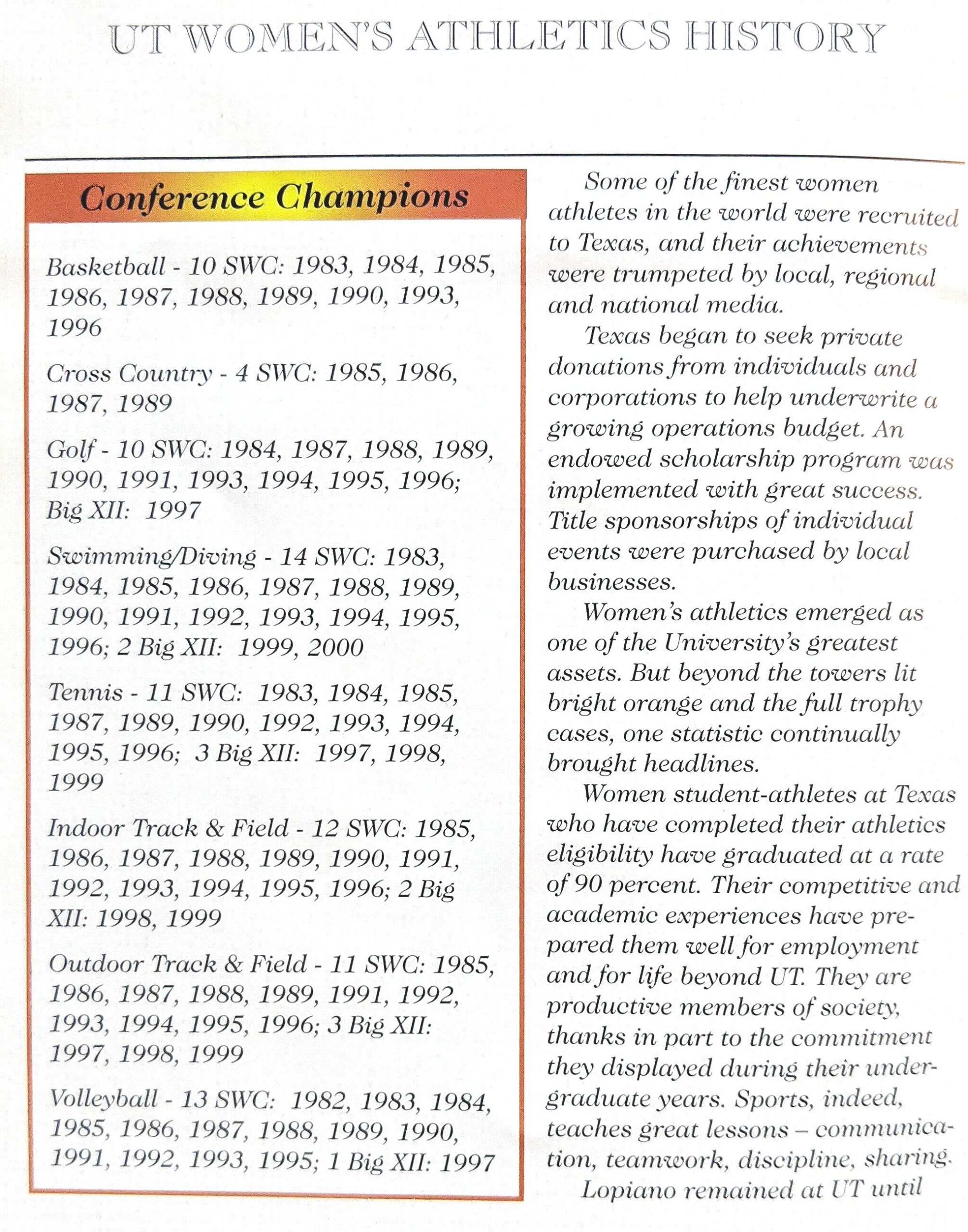

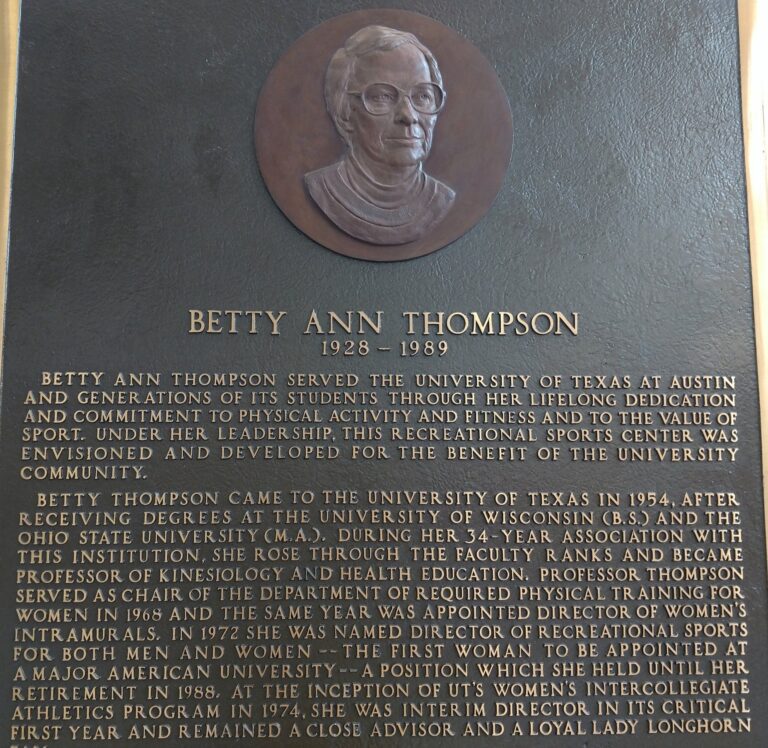

In 1966, The University of Texas women’s budget was $700; by 1983, the budget was $1,000,000 with receipts of 1,850,000 dollars.

-

1990’s

-

A Brief History of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Role in Regulating Intercollegiate Athletics By Rodney K. Smith

-

2022, 50 years later -Links to the History of Title IX

Starting in the mid-1970s, women were only limited by their capabilities, not by archaic rules that stifled the competitive spirit.

The History of Title IX

In 1966, The University of Texas women’s budget was $700; by 1983, it was $1,000,000, with receipts of $1,850,000.

http://www.titleixtexas.com/history.html

1972, President Richard Nixon signed the Title IX Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. The amendment required all universities that receive federal funds to offer equal opportunities for men and women in athletics and academics. Universities were given six years to comply with the new law.

The AIAW replaced the 1967 Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (CIAW). The organization moved forward aggressively to form a national intercollegiate women’s sports organization after Title IX’s implementation in 1971. Women assumed leadership positions as head coaches and athletic directors. The AIAW filled a need, and membership grew. Twenty-four thousand female student-athletes participated in the AIAW in 1972; the AIAW provided an alternate model for intercollegiate athletic governance- one dedicated to the educational value of athletics as a part of a more extensive educational program. The AIAW assured athletes’ rights and freedom from exploitation. The AIAW focused on students first and athletes second.

The first delegation met in 1973 at Overland Park, Kansas.

The AIAW organized and administered a complete national championship program offering 41 national championships in 19 different sports, including badminton, basketball, crew, cross country, fencing, field hockey, golf, gymnastics, lacrosse, skiing, soccer, swimming and diving, synchronized swimming,fast-pitch softball, slow-pitch softball, indoor track, outdoor track and field, tennis and volleyball.

Interestingly, The NCAA initially raised money to fight the implementation of Title IX. When faced with the threat of equality in intercollegiate athletics, the first approach of the NCAA was to attempt to limit Title IX’s application. The NCAA tried to offer its interpretation of Title IX (Acosta & Carpenter, 1985). It encouraged a narrow interpretation of the law, excluding athletic departments from the scope of Title IX. The NCAA argued that athletic departments should be excluded from compliance because they did not receive federal funds.

While the NCAA chose to fight Title IX, the AIAW started building a viable organization, and by 1979, The AIAW membership peaked at 800 colleges and universities and 100,000 student-athletes.

During its first year, the AIAW sponsored seven women’s national championships. In later years, the national championships increased to 17 in 12 different sports – cross country, field hockey, skiing, softball, tennis, gymnastics, track and field, badminton, volleyball, swimming, diving, and basketball.

From 1972 to 1982, AIAW championships were recognized as qualifying events for selection to a U.S. Olympic team, the Pan American Games, and the World University Games.

1977

Jo Ann Kurz says about her tennis coach, “Betty Sue was an excellent coach. She helped me learn doubles, and that helped my singles game. She was very patient as I developed more in my junior and senior years….”

“Significantly, I saw the change in women’s tennis with Title IX. I got a tuition waiver my first two years, then more assistance my 3rd and 4th, perhaps, a partial scholarship.”

We went from riding in Betty Sue’s Volkswagen bus to Arizona to flying to the Braniff Mixed Championships in Michigan, all because of more funding. We taught lessons for the Austin Tennis Foundation to bring money in for our team before we had enough funding to fly to team events.

Thank you for hearing pieces of my past at UT. It was a lot of work for us, and it is nice to know that the women following us have had a smoother path.”

According to the book “Life of a Coach (The Story of Pat Weis)” by Mickie Edwards, the AIAW rules stated that a female athlete could transfer freely to any university because neither scholarships nor financial assistance would be extended to the female student-athlete.

#2 Was the merger of the AIAW into the male-dominated NCAA worth it?

The question, “did the NCAA truly value women like women value women”? The answer is a conditional YES. But, of course, there were peaks and valleys along the way. Still, in conjunction with the leaders of the University administrations, the NCAA has added value to women’s sports over the last four decades.

Before ESPN and Fox Sports, UT gained exposure for women’s sports and negotiated a broadcasting agreement with the local stations KVET and KLBJ. In later years, UT learned that the only way the media would consider more exposure for collegiate women’s sports was to broadcast women’s sports to gain access to U.T. football and men’s basketball broadcast rights. Media that refused not to broadcast had no access to Texas football or basketball.

In 1979, ESPN started broadcasting intercollegiate women’s basketball, and the viewership of T.V. grew exponentially.

Not all was fair or objective for men when women gained equal rights to participate in sports.

With the advent of Title 9 and the decision to use proportionality as a tool to give women more prominence in college athletics, an alarming finding was revealed.

Title 9 challenged the college athletic world created by football, asserting that women deserved equal rights and scholarships to play sports in college. Title IX calls out the conflicting purpose of college sports. Sports for all are part of the college experience for students and should be a part of the educational purpose. Title IX said the goal of college sports activities was to provide meaningful athletic experiences for students no more or no less in degree than students involved in music, theatre, journalism, or literary college programs. Naïve analogy, yes, but in theory, college athletics was supposed to be a part of the educational experience, not a university recast in the image of big-time football.

Title IX forced college administrators to make decisions on which sports to support. Sports running a deficit were called out, and many were eliminated. It was tough for the colleges to balance finance, academics, and athletics.

Universities decided that minor sports should be reduced even though, in theory, athletic participation in college’s initial intent was to be a part of the educational process. Coaches of wrestling men’s track and men’s gymnastics blamed Title 9 for their loss of teams and athletes. Women responded that Title 9 was not to blame, but 90 players on a football roster were the culprit. If the football roster was 60, more wrestlers and runners could receive scholarships, forgetting that football created modern college athletics, leading to Title IX.

#3 The History of Title IX 1980’s

1980’s

By 1980, the AIAW renounced the “no” scholarship offer for women, but that decision came too late. Legal, commercial, and market forces decimated the AIAW membership, and the NCAA became the governing body for all men’s and women’s college sports. The Longhorn women’s athletic program disagreed with the decision to dismantle the AIAW. Stating the NCAA’s decision to disallow student-athletes in the organization’s governance and “using its financial monopoly in men’s sports to acquire women’s sports” was wrong. UT was concerned that the NCAA was too commercially driven and considered student-athletes as “investment property.” Many felt that women would not get fair representation in the male-dominated NCAA.

1981

But by 1981, the NCAA knew they had made a mistake by not supporting Title IX 100% and chose to recant their past statements and fully support women’s sports at the university level. The NCAA reasoned that if Title IX were to apply to intercollegiate sports at all levels and women were to be elevated to a status equal to men, the NCAA’s financial assets and political power would be threatened.

In “A History of Women in Sport Before Title IX,” the author Richard Bell states, “The NCAA became concerned their negotiating position as the dominant and controlling body of intercollegiate athletics was compromised.

The NCAA offered:

(a) pay all expenses for teams competing in a national championship,

(b) charge no additional membership fees for schools to add women’s programs,

(c) create financial aid, recruitment, and eligibility rules that were the same for women as for men, and finally,

(d) guarantee women more television coverage. The NCAA had earmarked three million dollars to support women’s championships.

Because of the NCAA’s wealth, political influence, and long, successful history, the AIAW eventually lost the battle to represent women athletes in college sports. The AIAW could not compete with the NCAA inducements, and the loss of membership, income, championship sponsorship, and media rights forced the AIAW to cease operations on June 30, 1982 (Festle, 1996).

The AIAW sued the NCAA for allegedly violating the Sherman Anti-Trust Act but was unsuccessful. The courts ruled that the market for women’s athletics was open for competition; therefore, no anti-trust laws had been violated (Schubert, Schubert, & Schubert-Madsen, 1991).

Resistance to the NCAA was fierce among many AIAW members. Some thought the NCAA would end women’s control over women’s athletics. Many felt that women’s sports would be considered an adjunct to the NCAA, and women would not be able to control their destiny.

In Tessa Nichols’s thesis titled ORGANIZATIONAL VALUES AND WOMEN’S SPORTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS 1918-1992, she states that Lopiano commented in an interview that football spending was an “embarrassment of riches” and that football revenues should be “shared among all the sports.”

Donna Lopiano stated in an interview for the 1983 UT Cactus that she discussed the demise of the AIAW. Here are some of her comments in bullet form:

-

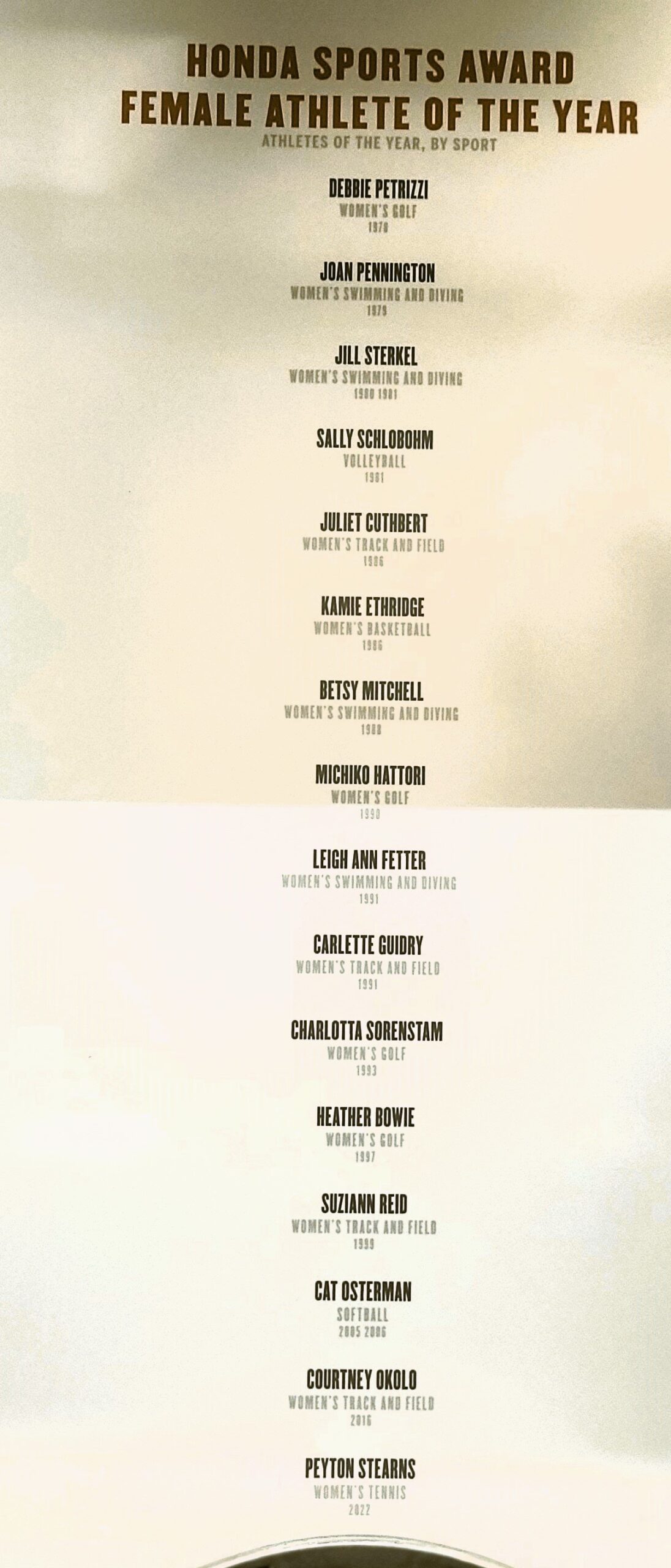

From 1982 to 1992, Texas won 61 conference championships and 15 NCAA titles.

-

Game attendance to basketball and volleyball games shot to record levels.

-

The Longhorns hosted the first sold-out NCAA Women’s Final 4 in 1987.

-

Total Performance was the rallying cry of Longhorn women’s sports. Student-athletes received total support academically, in Sports medicine, and athletically.

Life skills and career development components prepare the student-athlete for the post-college environment.

The switch from the AIAW to the NCAA cost A.D. Donna Lapiano’s department $153,000. Donna said her primary objection against the NCAA dealt with the stresses of recruiting. (Coaches did not recruit much under the direction of the AIAW.)

Lopiano said the coaches she hired knew how to build a winning program with an educational priority. She said that in 9 years, only five scholarship athletes left the program due to academics. She also said that only 50% of all general UT students graduate from U.T., but 95% of the student-athletes graduate.

Lopiano says that President Lorene Rogers was instrumental in the financial success of the women’s program. Lopiano was proud of U.T. President Rogers when she said the tower should be lit for Longhorn’s victory in women’s athletics.

She also noted that AD Darrell Royal played a vital role in women’s athletics’ successful financial health. Lopiano said that DKR did the right thing in not being pressured to fund both women’s and men’s sports because if he had, “both departments would have gone under.”

Donna Lopiano and DKR understood that the women’s program had to support itself by financially finding alternate sources of funds.

In 1983 those alternative sources of funds included $500,000 from optional student athletic taxes, $250,000 from gate receipts and program advertising, $250,000 from the option seating football program, and $850,000 from the auxiliary enterprise’s account interest.

#4 1990’s

1992

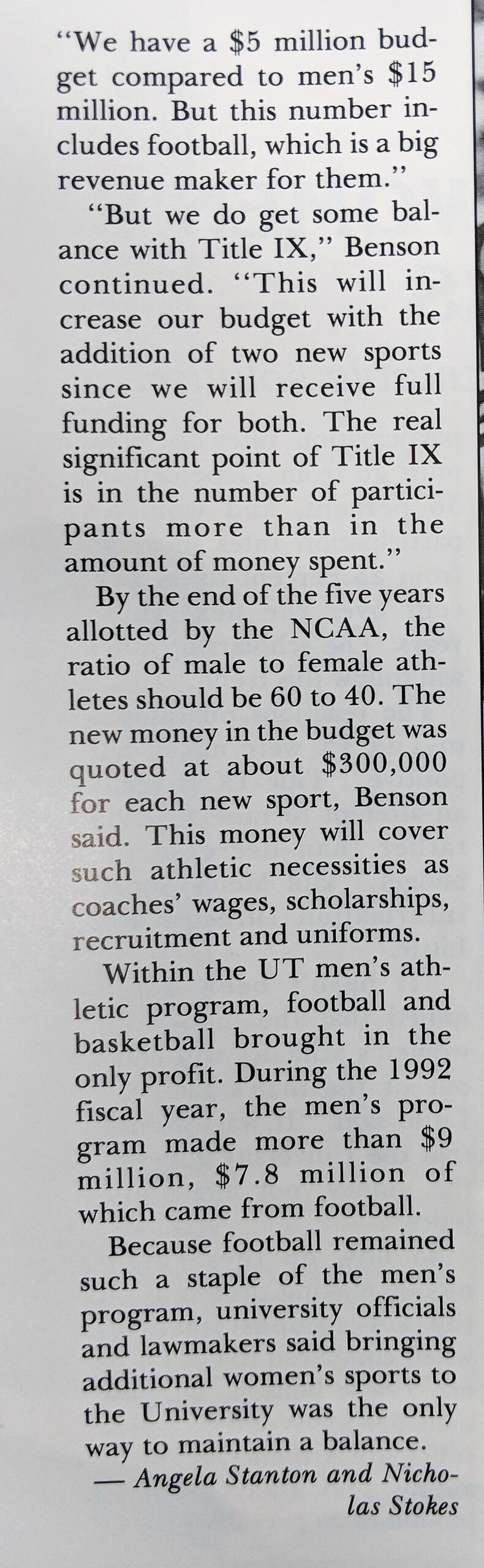

Seven female athletes filed a lawsuit against the University, charging that it had failed to comply with Title IX. Only 37% of the athletes were women, and women only received 1 million dollars of the 3.8 million budget for scholarships. Jody Conradt, executive director of the Women’s Sports Foundation and U.T. interim women’s A.D., was instrumental in settling the lawsuit by adding three women’s team sports- soccer, softball, and rowing. Texas Athletic budget was 41.2 million dollars.

1993

Jody Conradt assumes the job full-time as A.D. of the Longhorn women’s program.

Finally, in May of 1993 – 21 years after implementing Title IX- UT settled all lawsuits for non-compliance issues related to Title IX by adding women’s soccer, softball, and rowing to its list of sanctioned NCAA sports.

1999-2000

Texas women start Hall of Honor and recording Longhorn sports history

However, as late as 1999, the “gifts” from donors were a paltry $250,000. But that changed when Red McCombs had an epiphany, watching his granddaughter struggle to find an organization and facility to participate in softball. So when softball climbed to an NCAA authorized sport, he donated $3,000,000 to build the McCombs Softball Stadium;

By 1999 Sports Illustrated ranked Texas as one of the top 3 colleges for woman’s athletics.

#5 A Brief History of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Role in Regulating Intercollegiate Athletics By Rodney K. Smith

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 11 Issue 1 Fall Article 5

With some emphasis on proportionality in opportunities and equity in expenditures for coaches and other purposes in women’s sports, new options have been made available for women in intercollegiate athletics.

However, the cost of these expanded opportunities has been high, particularly given that few institutions have women’s teams that generate sufficient revenue to cover the cost of these added programs. This increase in net expenses has placed significant pressure on intercollegiate athletic programs. As a result, presidents of universities are cost-containment conscious, desiring that athletic programs be self-sufficient.

Therefore, revenue-producing male sports have to bear the weight of funding women’s sports. This, in turn, raised racial equity concerns because most of the revenue-producing male sports were made up predominantly of male student-athletes of color, who had to deliver a product that produced not only sufficient revenue to cover its expenses but also a substantial portion of the costs of gender equity and male sports that are not revenue-producing. Thus, the gender equity and television issues have mainly been economical in their impact, but they indirectly impact the role of the NCAA in governance.

Since football funding has been diverted from the NCAA to the football powerhouses, the NCAA, for the most part, has had to rely even more heavily on its revenue from the lucrative television contract for the Division I basketball championship. Heavy reliance on this funding source raises racial equity issues since student-athletes of color, particularly African-American athletes, are the source of those revenues. Thus, the NCAA’s very governance costs are covered predominantly by the efforts of these student-athletes of color. This inequity is exacerbated by the fact that schools and conferences rely heavily on revenues from the basketball tournament to fund their own institutional and conference needs.’

In 2007 the United Nations released a 44 page study titled

“Women, Gender Equality, and Sport”

“Sport provides women and girls with an alternative Avenue for participation in the social and cultural life of their communities and promotes enjoyment of freedom of expression interpersonal networks new opportunities and increased self esteem.

It also expands opportunities for education and for the development of a range of essential life skills including communication, leadership, teamwork and negotiation. Women and girls and the communities they live in all do better when they are allowed meaningful opportunity to compete in sports

Major events like the Olympics or important to women’s sports because they bring awareness to places where women’s sports have little visibility. These international tournaments make sport more accessible and makes female athletes legitimate in a way that they otherwise would not be.

To see these big brand corporate names around a well organized tournament with many cameras at the World Cup in 2015 devoted to the women’s game absolutely legitimizes it. Page 238 and 239 of the book “Loving Sports”.

#6 2022 50 years later

Links to the History of Title IX

Title IX: Top moments throughout history of women’s sports – Sports Illustrated

Sports Illustrated June 2022 Title IX anniversary cover – Sports Illustrated