1960’s Football- Halsell, Brame, McArthur, Talbert, Campbell, Brown, Feller, Hudson, Treadwell, Lott, Culpepper, Carlisle, Baer

1960’s T-Ring Reflections –

Glen Halsell, The Talbert’s, The Cleburne Boys, Garry Brown, Happy Feller, Jim Hudson, John Treadwell, Greg Lott, George Brucks, Duke Carlisle, and Linus Baer

Tom Harper Longhorn football mid-1960s remembers his teammates

I remember vividly our first day of 1964 Freshmen football practice and meeting for the first time my fellow teammates! We were at Clark Field & dressed in shorts, helmets, shoulder pads & football shoes! There were 50 four-year scholarship players, 25 one-year scholarship players & 10 plus walk-ons! Almost everyone was an All-Stater from 4A, 3A, 2A & even 6 man football! Wow, great memories! Tom Harper

Glen “The rolling ball of butcher knives” Halsell

Glen’s Halsell has been a free spirit his whole life. Some individuals lives beat to the sound of a different drummer but Glen’s drum sounds like no other. Glen spent a lot of time under DKR running the stadium stairs for his drum beat. But his drumbeat also made him one of the best Permian Panther and Longhorn linebackers of all time. Even though he ranks 4th behind #1 Tommy Nobis, #2 Derrick Johnson, and #3 Johnny Treadwell (Britt Hager ranks 5th), he has fallen into the Bermuda Triangle of Longhorn football history with no Longhorn honors to celebrate his accomplishments.

He is not even in the High School of fame after being named to the High School All American list and leading the Permian Panthers to a state championship in 1965. Part of the reason he has been forgotten is by his own choosing. He has chosen to live a private instead of a public life.

I believe at 75 years of age, it is time to publicly honor Glen for his accomplishments. If for no other reason, than to allow his teammates a moment of reflection. A moment for team members to vicariously celebrate their personal accomplishments in building the Permian Panther tradition embodied in Glen Halsell.

Article from the Vault 1967

Glen Halsell is one of the greatest linebackers in Longhorn football history. Halsell was only 5 feet 11 inches tall but was known as a fierce hitter and had 263 tackles in three years at Texas. In Glen’s debut his sophomore year, Royal could not wait to turn him loose against USC to knock some enemy heads together instead of those of his teammates at practice.

A stubby 200-pounder, Halsell maintained the tradition of the great Longhorn linebackers of the past. Glen said, “You sort of feel ’em behind you,” says Halsell. “Pat Culpepper, Timmy Doerr, Nobis, Edwards…Ever since I got here, the idea kept pushing me that I was filling some mighty big shoes.”

“You got to be tough,” Halsell says. “I mean, really think about it. Joel Brame is my idol. Against Rice last year he got his nose laid open to the bone, but he never came out of the game. It was so bad he’s going to need plastic surgery.” End of Vault article.

Halsell said “The hardest thing for me is playing my position,” he said. “I can’t go running off after the ball until I’m sure what’s going to happen.” Royal doesn’t seem too worried about that.

Royal said Glen was a rolling ball of butcher knives. He was so good at his skill set that he was the only defensive player that got away with throwing the pending game plan into the trash when he left the meeting. He told the coaches “that all that information just confused him. He said my game plan is to tackle the ball carrier.”

Halsell was one of the tri-captains of the ’69 national championship team.

Regardless of drumbeat, his teammates love and respect him. Most of those in the photo below have been Glen’s friends for 6 decades. I am one of them. On April 3rd, 2016, on the way to Big Bend, I stopped in Fort Davis for a short visit. We shared a few stories and laughs, and then we said goodbye with a hug that reflected our mutual respect, our common bond, and our shared experiences. As we parted ways, my belief that life has little meaning without family and friends was re-confirmed. Horns up and a big MOJO for Glen Halsell.

The Permian State Championship reunion is taking place. Glen is seated next to yours truly on the front row, and on the third row is former Congressman Mike Conaway, second from right, next to Phil Fouche.

The Story of Glen Halsell is told by author Terry Frei in his book Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming.

The three campus police cruisers Glenn Halsell could handle. The cop cars were up on the sidewalk, and lights flashed surrounding him. He, after all, had only been a gentleman and obliged the girl who asked him to deliver her back to the dormitory after the party. Also, the Longhorn linebacker made sure she didn’t have far to walk, pulling his car up over the curb, onto the sidewalk, and up onto the front steps of the dorm’s entrance.

The humorless cops and whoever called him didn’t appreciate his chivalry. He was pulled into one of the squad cars. He was in the back seat waiting figuring he could handle the wrath of the law regardless of what these flat feet decided to do with them. But all they were doing were doing was sitting and waiting.

Then Halsell’s heart damn near stopped. Suddenly he knew he was in trouble. The orange Cadillac convertible was pulling up. It was three in the morning long past bedtime in the home of Edith and Darrell Royal. Having to get out of bed and pull on clothes and go kick one of the boys in the ass wasn’t going to thrill the head coach. The cops pointed. Halsell climbed out of the safety of the cruisers back seat and got into the car with one angry football coach. Halsell was scared Sober.

Royal says “Glen what are we gonna do with you. You can’t go through life this way. Straighten yourself out! You only get so many chances in life son and you’re running out of them. Royal drove Halsell the toughest meanest damn football player on his roster back to his dorm.

End of Glen Halsell story

The THE PROTOTYPICAL DKR LONGHORN football players

Most of the players recruited in the 1960s had a similar build and character to the Cleburne Boys. Tim Doerr, David McWilliams, And Pat Culpepper represent all the qualities DKR wanted from a Football Player. All are under 200 pounds, are instinctive players, and are motivated to win. All Three knew How To Play And With Wit Their Opponent.

Pat Culpepper

David McWilliams

Tim Doerr

George Brucks

Some of the East Coast sportswriters thought Royal’s players were”slow guys with skinny legs and big butts.” But One of the Navy players in 1963 knew better. The Navy player, who played professionally, said competing against Jack Lambert in the NFL was easier than playing against Texas players. He said, “the guy in my nightmare is George Brucks from Hondo, Texas, “who weighed under 200 pounds, but “he took my head off All day long.”.

George is #66 in the pictures below.

Brucks #66

Brucks #66

Garry Brown

Many football team members received very little recognition during their four years at Texas. They only participated in practice and Spring Training, with no playing time on Saturday. Garry Brown was one of these players.

While Coach Royal was tough on his players, he also had tremendous respect for team members who competed hard at practice. Garry Brown was that kind of teammate. Unfortunately, he had never suited up for a varsity game.

Royal rewarded his patience and perseverance in the final conference game in 1964 against Texas A&M. With 2 1/2 minutes to play and the Texas victory secure, Royal told Garry Brown to go in on defense.

On A&M’s next three plays, Garry had one tackle and two assists. Then, with 30 seconds to play, Royal put Garry in the game on offense, and Garry caught a 19-yard pass followed by a 10-yard TD catch as the clock ran out. Garry said, “I was in the form of shock. My teammates were more excited than me. They were in unbridled joy. It is and was a great memory.”

HAPPY fELLER

Happy Feller, the kicker who booted the last point in the Longhorns’ 15-14 win against Arkansas in the 1969 game dubbed “The Game of the Century,” said Royal kept the players on their toes back in the day. H

HAPPY FELLER WAS AN ALL-AMERICAN IN 1970 and is in the Longhorn Hall of Honor.

Happy talking about playing for Coach Royal

“He was one of these types from that particular era that tried to keep an arm’s length between himself and the players,” Feller told Sporting News on Wednesday. “He was the type that if you had a couple of bad series, he was not opposed to pulling you out and putting in the next guy.”

“When you came in the locker room, you had to turn to the left to go to the lockers, and right there on the wall was the depth chart.” Everybody was on one of those little hooks. You looked at it every day. Royal was the type that if you didn’t hustle in practice, the next day, you’d go into the locker room, and you were No. 2 or No. 3, and somebody else was No. 1.

“I think that’s an important lesson for kids today. It’s not only important during the game in how you perform but also that you better be at your best at practice and hustle because if you’re going to loaf around out there, then when you come into the locker room the next day, you’re not going to be in that No. 1 slot. That’s the way he was. That was always his philosophy.

“The guys that really administered a lot of the discipline were all of his assistants. The last thing you wanted was a page to your room or somebody to tell you that Royal wants to see you in his office. That was the fear of God.

“One time, I got that page. There was a little restaurant in Austin called English. They were having some kind of special one weekend. It was a roundup in the spring when all the different fraternities had different events going on. They wanted me to come down to be in an ad for this food special. They had food on the table and a pitcher of beer on the table. I didn’t think anything of it when they took these pictures. Sure enough, I get a phone call from Royal’s secretary: Coach wants to see me in his office. He had that picture in the paper and asked, ‘What is this? Why in the world would you be in this ad with a pitcher of beer and a mug of beer on the table?’ I was so embarrassed. Those were the kinds of things he watched for. Needless to say, I never made that mistake again.”

Jim Hudson

Jim Hudson

From Wikipedia

Jim Hudson played at various times wide receiver, running back, defensive back and quarterback at Texas, and also returned punts. He began at Texas in 1961, and in 1962, his first year on the varsity, he played wingback and defensive back. The following year, he played defense on the team that won the 1963 National Championship. That season he led the team in interceptions and recorded five tackles in the 1964 Cotton Bowl win over #2 Navy. At the start of the 1964 season, Hudson was moved to quarterback, but he was injured before the season started and replaced by Marvin Kristynik. Hudson’s only start at quarterback came in the 2nd week against Texas Tech. He was injured on the first scoring play at the end of the first quarter and replaced by Kristynik for good. He saw little play for the rest of the season, until the 1965 Orange Bowl against #1 and National Champion Alabama. Kristynik struggled early, and Hudson was put in after a penalty turned a punt into a first down. He hit George Sauer for a 69-yard touchdown pass and helped lead Texas to victory. In the process, he attracted the attention of Jets scouts who had come to watch Crimson Tide quarterback Joe Namath.

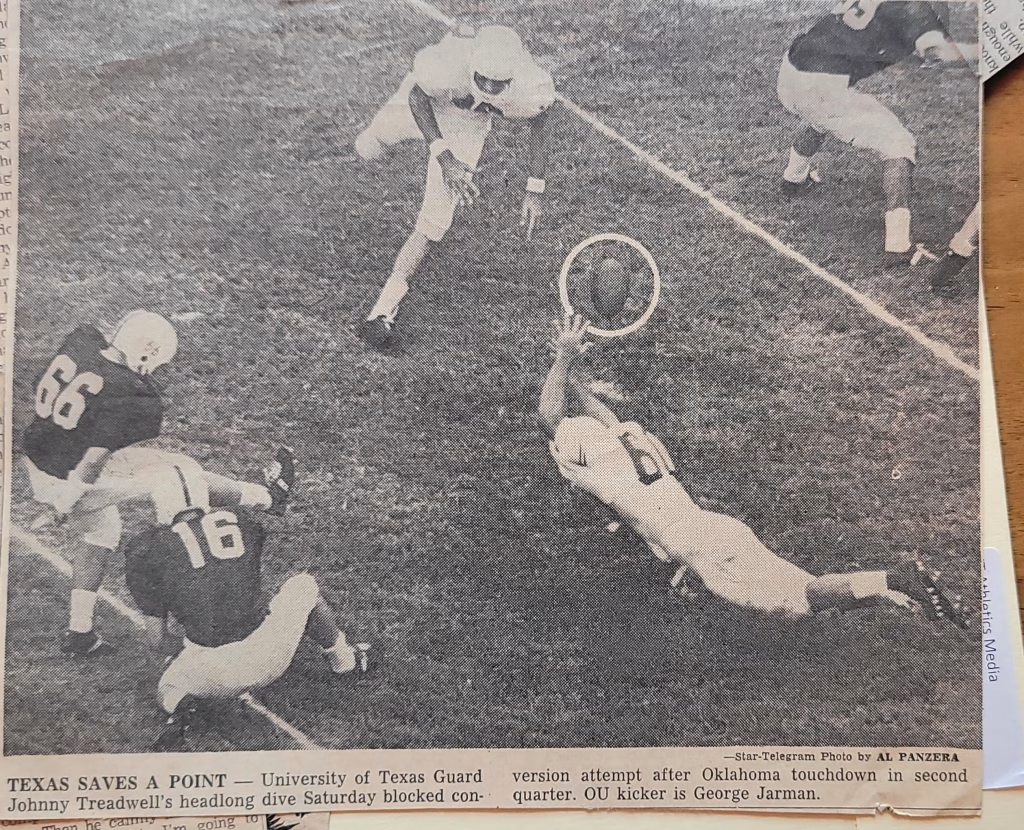

John Treadwell

His teammates called him “Stoneface” because he normally regarded conversation as wasted energy on the field. But when he did speak, people listened. Defensive coordinator Coach Campbell said John was a “crushing tackler.” “Treadwell was quiet, moody, and an introvert who psyched himself into mental readiness.” “ He just kind of starts swelling up,” said offensive line coach Russell Coffee about Treadwell’s preparation for a game.” He gets a blank stare on his face. He won’t talk to anybody.

Royal said, “The mark of a great football player is one who has his best games against a great team.” Treadwell had no bad games while at Texas,

The comments below are from Pat Culpepper’s articles in Inside Texas.

“Let’s kick their ass.” Those were the words Johnny Treadwell spoke to me before the kickoff of Longhorn games from 1961-1962. We were on either side of Eldon Moritz in 1961 and Toby Crosby in 1962. So when No. 60 Treadwell would look across at me and give me his short-to-the-point battle motto for games against Oklahoma, Arkansas, Rice, A&M, and our bowl games, I was ready.

When I told that to my wife, who did not know me during my football days at Texas, she said, “Did y’all really talk like that?”

My answer was, “To Johnny, football was war.” He was the number “60” at Texas before Tommy Nobis, before Britt Hager. Perhaps Texas fans don’t remember those days anymore or perhaps don’t care, but Treadwell’s story is worth remembering. He played at a time when the Longhorns came of age in the Southwest Conference. Darrell Royal had yet to win a bowl game at Texas. Johnny was born and raised in Austin and played High School Football at Austin High, but in his senior year, he broke his arm early in the season and was overlooked by recruiters except for West Point, who were attracted to his grade point average and recommendations by his high school coaches.

The fact is, it was a Temple DL coach who told Mike Campbell, who was the Texas defensive coordinator for Royal’s 20 years as head coach, that “the best lineman in our district is the Treadwell boy at Austin High.” Campbell sat in the Austin High School fieldhouse and watched Treadwell on preseason scrimmage films and the couple of games he played. Those were the days of 50+ plus on football scholarships, and Campbell made him an offer.

He was an end on the freshman team at Texas but had “Hammer-Hands,” as his teammates called him. That ended when he was shifted to offensive guard and also played linebacker on the 1960 varsity team. The most he weighed at Texas was 205 but he had the ability to make smashing collisions when he tackled. As a guard, he used his quickness to beat defensive players to the punch. In 1961, he began to call the signals in the defensive huddle and would add his remarks that set the stage for big plays. Those were the days when Memorial Stadium only sat 64,350, and Darrell Royal’s first sell-out came on a hot night when the No. 1 Longhorns faced Frank Broyles’ Arkansas Razorbacks, who were ranked No. 7 in the nation and were also undefeated. The year was 1962. There were no more tickets, and some Arkansas fans cut through the fence in the back of the south end zone and got on the track around the playing field. National media were there from Wednesday all the way up to the game, interviewing players at lunch at Moore Hill Hall and then attending practices. In those days, Texas was only allowed national television for the Oklahoma, A&M, and bowl games, so people to this day remember the Kern Tipps broadcast that night or treasure the fact they were in attendance.

The 1961 season had set the stage for such a game in many ways. The 5-0 Longhorns had been the nation’s No. 1 team, often beating Rice 34-7 in Austin, and then held off an SMU team on the goal line just before halftime with their old Rose Bowl team standing in the end zone yelling encouragement. Treadwell and the other Texas linebacker stacked SMU’s fullback on fourth down one yard shy of the goal line. James Saxton raced 80 yards on a counter-trap play to ignite a 27-0 Texas victory in the 2nd half. Baylor was crushed 33-7 in Austin. TCU upset Texas 6-0 to knock Texas out of the top ranking, but the Longhorns rebounded at College Station, putting a 25-0 whipping on the Aggies, and that brought on the Cotton Bowl and the Ole’ Miss Rebels under Coach Johnny Vaught. Only a 10-7 loss to LSU separated Vaught’s team from an undefeated season, and Royal, while head coach at Mississippi State and then at Texas, had never beaten the Rebels, much less won a bowl game as a coach. Period.

Click here to listen to the radio interview with Pat Culpepper after Coach Royal passed away.

In sunny, 41-degree weather in Dallas, Texas, intercepted five Ole’ Miss passes, one on which “Hammer Hands” Treadwell slugged the ball high in the air that cornerback Jerry Cook picked off, killing the Rebel’s possible fame-winning drive. Texas won 12-7, and thus the Longhorns, who ended the 1961 season as the Nation’s number 3 team, entered the 1962 season as the number one team, which set up the huge game with Arkansas on that humid night. Arkansas was averaging 34 points a game, which was unheard of in 1962. The stage was set in Austin with both teams 4-0. At the end of the third quarter, with the Razorbacks holding a 3-0 lead, they reached the Texas 5-yard line where the intense Treadwell said these words in the defensive huddle, “We’ve got them where we want them. They have run out of room. They can’t throw a long pass. They have got to come at us. Ready… Break!”

Two plays later, the Razorback fullback trued the counter on the Longhorn line and was met by Treadwell and his fellow linebacker. The ball came out, tumbling into the end zone, which Joe Dixon recovered in a mad scramble.

Treadwell #60 Culpepper #31

As if that wasn’t enough, Texas fumbled the ball at its 22-yard line, and Arkansas drove to the 12 and on fourth down. QB Billy Moore tried a sneak at the Texas right side only to be hit squarely in the chest for no gain by Treadwell. The game ended with a 90-yard drive by Texas with Treadwell at guard on 20 plays with a Longhorn touchdown for a 7-3 win.

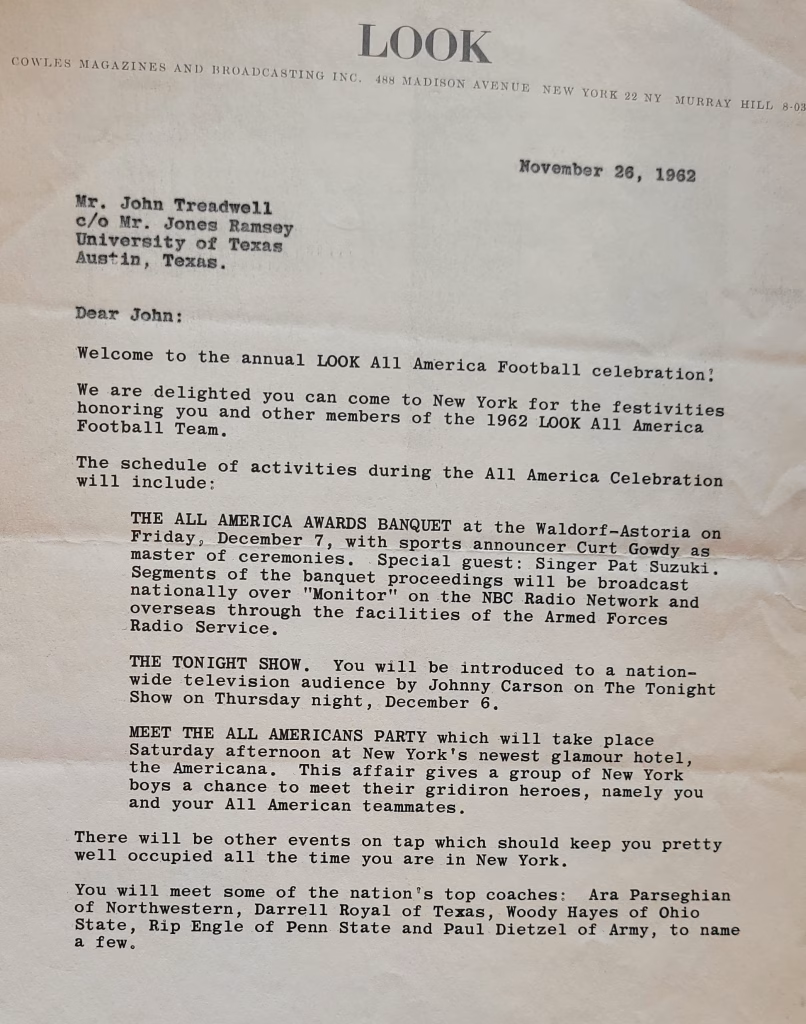

Following that season, Treadwell was named to the All-American team and met President John F. Kennedy at the Army-Navy game on his way to New York to receive his award on Ed Sullivan’s TV show. After graduating from Texas, Johnny got an agricultural degree from Texas A&M and became a Vet in Austin.

Those spring days when I would ride in his Jeep in the countryside and talk about what we wanted to accomplish in the fall were priceless. He had a great smile and loved to laugh. He married Peggy, a beautiful woman, and they made a great team in his veterinarian business. It was Peggy who attended Johnny so beautifully when dementia began to take over. The action photograph of Treadwell and the Texas defense knocking out the football on that goal line play versus Arkansas use to be in the defensive room of the Longhorns and was the only action photograph Darrell Royal had on his wall during his last days at the Baton Creek assisted living facility.

His teammates called him “chopper” for the way he got to the job alone and I was proud to call him “Johnny.” I miss him already.

Chopper

Tommy Nobis said it best: “The real number 60 was Johnny Treadwell.” God Bless his passion, courage, and friendship.

Tommy Nobis honors Johnny Treadwell

He was the best because he gave it all he had. What more can any person do? That passion rubbed off on those who played around him. There was no “faking it”. It was real and made us winners while we were at Texas.

Future Texas players will need to be so passionate and dedicated to return the Longhorns to football prominence. Johnny Treadwell helped ignite this effort and dedication in the early 1960s, which brought about Conference and National Championships in 1963 and 1969.

Hook’em,

Pat Culpepper

Article About Greg Lott And Farrah Fawcett By Pat Culpepper

Greg Lott and Farrah Fawcett Texas Longhorns

Farrah and Greg the “hippie movement begins

In later years

The Comments Below Are part of the story From Pat Culpepper’s Article In Inside Texas. Visit Inside Texas to see the whole story.

Pat Culpepper says about recruiting Greg Lott as a Longhorn assistant coach

Greg Lott had Hollywood looks, and what was important to me was outstanding speed! His career at Texas was highlighted by brilliant interception returns in big games. He also played kick returner with some success. I was long gone from the University of Texas when Danny and Greg played, but I tried to keep up with them as best I could. I must admit that during my playing days in Austin, I often picked out future “dates” from the University of Texas yearbook. Those were the days…, and it wasn’t until my senior year that I settled down my dating activity to just one girl. No, it wasn’t what you think; they were movie dates, dancing dates, or double dates with my teammates to events in Austin’s downtown or one of those great Mexican restaurants. I was not ever in the class of Greg Lott. His girlfriend was none other than what would later become Hollywood blonde bombshell Farrah Faucett!

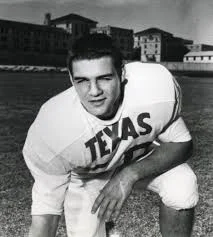

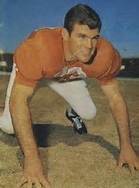

Greg, as a player

According to Greg, they were more than serious (whatever that meant) and should have been married, but Greg stayed in Texas, and Farrah went to Hollywood. She became famous with a beautiful, striking face that featured piercing green eyes framed by flowing blonde hair. Her fabulous figure in a bathing suit adorned many a teenage boy’s room and a few older “boys” as well.

Farrah died of cancer in 2009 at the age of 62, even more beautiful than she was at 22, at least from her heart. For so many, she left money and art treasures that she had earned and collected. Gregg told me that he began to see Farrah again in 1998, and they had a close relationship between their homes in Austin and Hollywood. It became a tabloid topic because she had split with actor Ryan O’Neal.

Greg Lott and Ryan O’Neal

I have found out through friends that Greg went through a difficult time in his life in the ‘70s and early ‘80s, lowlighted by two drug convictions. Hollywood looks do have their drawbacks, I suppose. Farrah left Greg $100K in her will and absolutely nothing to O’Neal. The other notable possessions she left at the University of Texas included two famous portraits of her by Andy Warhol. They were done in 1980 in Warhol’s silk screen pop-art style, which featured her bright green eyes and red, red lips. One of the portraits is involved in a case in the Los Angeles Superior Court. The problem is O’Neal claimed that Farrah gave it to him, but University of Texas attorneys claim Fawcett got the portrait back in 1998 (when she got back with Gregg) and kept it at her Malibu home until her death.

O’Neal and Fawcett had split up in February of 1997 when she found him in bed with another woman. According to O’Neal, he gave the portrait back to Fawcett because his new girlfriend told him that the picture made her “uncomfortable.” The value of the portrait is said to be estimated at $12 million, although it is insured for $600K. O’Neal claims that it is his, but there were two of these portraits, and Fawcett’s will, which insured both drawings, only mentions that she was giving them to the University of Texas Art Department. In fact, it was Gregg Lott that brought attention to the fact that one of them was missing in the first place. The trial took place in Los Angeles, and perhaps predictably, Ryan O’Neal was awarded the portrait, even though Farrah had made no indication in her will that O’Neal would get anything. So a drama of sorts ends in court, but the true love story here told to me by Greg Lott was about the “time” that he and Farrah got to spend together before she passed away.

Greg 1965 and 2014

Lott

They enjoyed their time at U.T., and many years later, there was still a spark that was alive and well. I recruited Lott to U.T., Lott falls in love with a campus sorority beauty who turns out to be a future star in Hollywood on Charlie’s Angels and a pin-up queen in the 1970s-‘80s. I’m proud of my “boy” Greg, he was faithful to the end of Farrah’s life and he always yells, “Coach Pat” when he sees me. And in her defense, Farrah did remember her school and wanted to give them her most treasured possessions and left my recruit a parting gift of lots of money…you never know.

Duke Carlisle And The Baylor Game

The Interception That Helped Save The National Championship Year.

It was a surprise to be in the game at that point because we had the substitution rule[s] [which] were evolving, so you couldn’t substitute an entire team at any time. But we were able to switch individual players when we were on offense and when we were on defense. So, I always went out of the game when we switched to defense. We fumbled the ball near Baylor’s goal line towards the end of the game, and I started to leave, and they motioned me back. So that was the only defense that I played that year – it was the end of the Baylor game.

http://www.texassports.com/news/2013/8/29/FB_0829134208.aspx?path=football

People say, “Why was that?” And the first thing that comes to mind is that I played safety for the prior two years, so from that standpoint, maybe that would make sense. That was our eighth game of the year, and Jim Hudson, who had played safety, had had a great game that day and a great season leading up to it. So it is still not explainable to this day, and [defensive coordinator] Coach [Mike] Campbell made that decision. I don’t know exactly what he was thinking, but I was in there for Baylor’s last drive. They were close enough to the goal line that we didn’t have as much field behind us to defend, so that was one of the things that made it possible to get to the ball. It was exciting – obviously, an inspiring play, and the timing made it more memorable because it was at the end of a one-touchdown game. I have tried to remind people that when we talk about it – and not trying to be overly modest – but it was an incredible achievement that our defense held that offense scoreless that entire day, and that was one of the most high-powered offenses in the nation that year. They had not been able to get a point against us. So, I have tried to keep that one play from obscuring the fact that that was a great game by our defense.

It was an unusual situation, if you think about it. I wonder if Coach Campbell ever thought to himself that if the guy had caught the ball, people would’ve said, “What on Earth were you thinking, removing that great safety?” had they completed the touchdown. It wasn’t an easy thing to figure out, but it worked out well. And yes, Jim would’ve made the play; he has told me many times that he would have.

Linus Baer- The best game in the history of Texas High School football follows

Posted: Sunday, May 1, 2016 12:01 am

By Chad Conine, guest columnist

On Nov. 29, 1963, San Antonio Brackenridge faced off against San Antonio Robert E. Lee. The nation was still in shocked disbelief over the assassination of President John F. Kennedy a week earlier. In Texas, the unthinkable horror knocked us off our feet, because it took place on our watch in Dallas. The high school football playoffs were set to begin, but football coaches, players and fans wondered whether it was permissible to return to sport.

In San Antonio, the defending state champion Brackenridge Eagles drew the Lee Volunteers in the opening round. It was too good a game for fans to pass up, and so the people of San Antonio gave themselves permission to care about football, at least for a night.

The game sold 22,000 in-demand tickets as hundreds stood in line in the cold November rain, even all night some nights, during the week leading up to the Friday-night contest. Many more who failed to obtain a ticket watched the television broadcast on WOAI. Former players recall it as the first bi-district football game ever televised in the state.

I spoke with Linus Baer, one of the key players in the unfolding drama, in his San Antonio office in early February 2015. Before we met, Baer mailed me a copy of a documentary titled simply “The Game,” produced by Gary DeLaune, a Texas Radio Hall of Fame broadcaster.

In it, DeLaune unpacks all the elements that made this game special, using interviews with Baer, Brackenridge’s Warren McVea and other members of both teams.

But I still wanted to know more about the environment in the wake of a national tragedy. Having covered high school sports in the uncertain days following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, I wanted to see whether there were parallels. It seems there was the same sense of not knowing exactly how to move on.

Baer said no one wanted to play football a week earlier, on the day of the JFK assassination. He recalled how the teams walked through a ball game on a surreal evening. But a week later, football was something people needed to hold close.

“The Lee-Brack game served as a release, an outlet for people to go to the game or watch it on TV and enjoy it,” Baer said. “Get their mind off the Kennedy assassination, give them something else to think about. I think it did that. I think that’s one of the reasons people remember it so well.”

The Lee-Brackenridge game still resonates with football fans because of a rich collection of ingredients, both between the lines and outside them.

Brackenridge had won the state championship in the state’s largest classification in 1962, defeating Borger, 30–26, in the Class 4A title game. The Eagles entered the postseason in 1963 with an 8–2 record, but with a reputation to match that of any undefeated squad. Lee boasted a 10–0 regular season, but approached the game more like an underdog.

Both teams came in with tricks up their sleeves. Brackenridge shifted star running back McVea to quarterback in order to multiply his number of touches. But Lee’s philosophy not to punt and to employ only onside kicks was the slightly more dramatic strategy.

Each of those measures influenced the game from its early stages. As I watched the grainy black-and-white film of the contest, it’s easy to see why The Game electrifies football fans.

Though the documentary includes almost the entire game, it still plays like a highlight reel. Before the dust cleared and a winner was declared, the combatants would be smiling at each other on the field, shaking their heads in disbelief at how much fun they were having. They were playing football, but they were also bringing about cultural change.

In 1963, Brackenridge was made up of mostly African-American players and a few Hispanic players, while Lee was all white. Texas was still years away from full-scale integration, and in researching this book, I heard stories of racial hostility at ball games from much later in the tumultuous 1960s.

The Lee-Brack game had it where it mattered most. The storyline was uplifting when people needed it, but the play between the lines made it legendary, and the jaw-dropping action began with the opening series.

Lee marched for a touchdown on its game-opening possession, then recovered its first onside kick attempt. Baer scored to cap the second drive, giving the Volunteers a 14–0 lead before McVea or any of the Brackenridge offensive players had touched the ball.

But the Eagles were wise to Lee’s strategy after that, recovering every onside kick attempt the rest of the way. Down 14–0, the Eagles recovered the second one and went to work digging out of a hole.

McVea’s first run of the game at once justified both teams’ strategy and showed that the early two-touchdown lead wasn’t safe. McVea scrambled around the left side of his offensive line and then darted down the sideline for a fifty-four-yard touchdown.

Lee called a timeout the first time the Volunteers saw McVea step in at quarterback, but the powwow didn’t do much good. “It was a great call for Coach (Weldon) Forren to do that,” Baer said. “To get (McVea’s) hands on the ball every play was genius, because he could do things with the football that I’d never seen anybody do before.”

McVea’s high school career made him a sought-after football recruit who received dozens of college scholarship offers. He went on to the University of Houston, where he was the Cougars’ first African-American player.

Former San Antonio high school football standouts Warren McVea (left) and Linus Baer met with members of the media during a sports luncheon in San Antonio in 2007. San Antonio Express-News file photo

Viewed retrospectively, it’s no wonder that Forren put the ball in McVea’s hands on every offensive play on that cold night at Alamo Stadium.

McVea told me that Forren pulled him aside during the week leading up to the game and said the only chance the Eagles had was to move him to quarterback. McVea, of course, was on board. Brackenridge simplified its game plan to accommodate the change in strategy.

“I only had about four or five plays,” McVea said. “That’s all we did. We ran Floyd Boone off tackle, Floyd Boone around the end, Floyd Boone up the middle, and then me around the end. That’s all we had.”

For a moment in the second half, it looked as if that would be all the Eagles needed to advance, despite the fact that Lee had taken a 34–19 lead to intermission.

Brackenridge recovered Lee’s onside kick to start the second half and began taking control of the scoreboard. McVea scored two touchdowns in the third quarter, helping the Eagles win the third quarter 14–7, marking the first period of the game in which Brackenridge gained an edge.

The Eagles went to the fourth quarter trailing 41–33 but holding the momentum.

With 74 points on the board going into the final period, the early 1960s contest became the kind of evenly-matched offensive slugfest that delights fans. It not only resonated but also grew like a big fish story.

“If everybody was at that game that said they were at the game, there was like 100,000 people there,” Baer said. “Everybody you talked to was at the game or knew somebody who was at the game and always wanted to talk about it. And it was always called ‘The Game.’ ”

The players were loving it, too.

“After the game got going, what’s so amazing about that football game is all the guys on both teams started having fun,” McVea said. “While we were out there playing, me and Linus were just laughing and saying this is like a track meet.”

The Eagles needed a stop to start the fourth quarter in order to pull even with Lee. But Brackenridge made the most crucial tactical mistake up to that point by putting the ball in Baer’s hands in the open field.

Baer rushed for 150 yards in the contest and caught two passes for 95 more yards. He finished with four rushing or receiving touchdowns, but his biggest play came on the rare occasion that either team opted to kick deep.

He hauled in the kickoff in the first minute of the fourth quarter and found a seam up the left hash mark. Baer and McVea had formed a relationship during track season, and Baer knew that the one player capable of catching him once he cranked up his engine was McVea.

Only McVea, who kicked the ball deep and served as the last line of defense, was wearing human ankle cuffs.

“(A Lee blocker) fell down and crawled over there so I wouldn’t see him,” McVea recounted. “He had a leg lock, and I couldn’t get him loose. I looked down, and the guy had his legs around me in a leg lock. I was like, ‘What is going on here, man?’ And Linus ran it back for a touchdown.

“I had a chance to get him, and the referee let it go.”

The black-and-white film from DeLaune’s documentary confirms McVea’s story, though the film is a little too grainy to identify the Lee player.

Baer’s kick-return touchdown boosted Lee’s lead to 47–33 with more than 11 minutes remaining. Brackenridge wasn’t finished, though.

McVea, perhaps still riled up from being held, answered with a 46-yard touchdown run. On the point-after attempt, he grabbed the ball on a fake kick, scrambled to his left, and threw back across the field to complete the two-point conversion pass, cutting Lee’s lead to 47–41.

Then came the Eagles’ big break as they turned the tables by recovering an onside kick.

On the ensuing drive, McVea handed to Boone, who gained a pair of key first downs, setting up McVea’s five-yard touchdown run, which tied it. McVea kicked the extra point to put Brackenridge ahead, and for the first time, it appeared as if the defending state champions might survive the battle.

McVea scored the go-ahead touchdown with more than six minutes left. If the game had been played in the early 21st century, with both defenses exhausted and quick-strike offenses sensing blood in the water, six minutes would have been a virtual eternity.

But this was 1960s football, heavy on the run, so the last half of the fourth quarter represented the final gasp of a fantastic game.

Brackenridge came close to stopping Lee when the Eagles forced the Volunteers into a third-and-seven from the Brackenridge 28-yard line. But Lee quarterback Gary Kemph dropped back, pumped once, and then threaded a pass to Eddie Markette over the middle for a 16-yard gain to the Eagles’ 12-yard line.

From there, the Volunteers plodded forward until fullback Larry Townsend plunged into the end zone from one yard out. A successful two-point conversion put Lee ahead, 55-48, with a little more than 30 seconds left.

Though only a few ticks remained, Lee definitely didn’t want McVea touching the ball too many times.

“It seemed like a whole quarter was left to me,” Baer said. “I did all the kicking. I lined up, and I was going to kick it opposite where McVea was. He lined up in the middle, so I kind of angled over this way, and he moved over this way. Then I line up over there, and he moves over that way. And I just said, ‘Ah, hell, I’ll just kick it.’

“I kick to this guy, and he laterals it back, and now I’ve got to catch (McVea).”

The Eagles did corral McVea on the kickoff. Then, on the final play, from his own 43-yard line, McVea scrambled to his right, looking for the kind of hole that had been there so often that night. McVea finished with 215 rushing yards and six touchdowns, but he couldn’t get away on his last carry.

Lee tackled McVea and grasped a 55–48 win.

The Volunteers prevailed from the underdog role, but on this night, there was no room for chest pounding. The nation had lost its leader a week earlier, and perhaps more meaningfully in the context of the game, a white school and a predominantly black school from San Antonio had won each other’s respect through a thrilling football game.

The two principal players had formed a relationship going into the contest, but it was strengthened after the memorable night. They roomed together the next summer at the Texas High School Coaches Association All-Star Game.

Baer, who went on to play college football at the University of Texas, graduated from high school having formed an unusually tight bond with an athlete from another school.

“We played basketball against each other, ran track against each other,” Baer said. “He’d call me up and ask me to go to parties. We were good friends and had a lot of respect for each other.”

San Antonio has long since had a reputation as a culturally and ethnically diverse city. An attempt to explain the reasons and roots of that distinction would fill up another book. But the players involved in the classic football clash of Nov. 29, 1963, credit that experience with playing a huge role in the city’s evolution.

“What really, I think, happened is it drew the communities closer together,” McVea said. “Robert E. Lee was kind of like the mother ship in all that stuff. They didn’t have any black players. The thing that really stood out was how the guys on the other team treated us. They treated us with a lot of respect.”

Excerpted from “The Republic of Football: Legends of the Texas High School Game,” © 2016 by Chad Conine. The book will be released in September by the University of Texas Press.

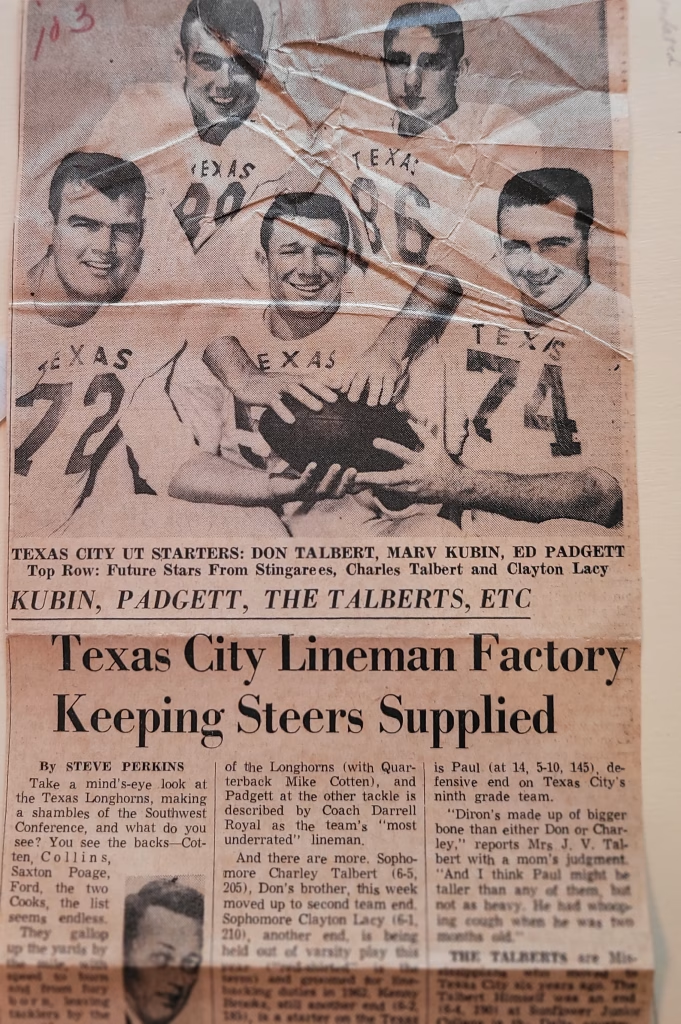

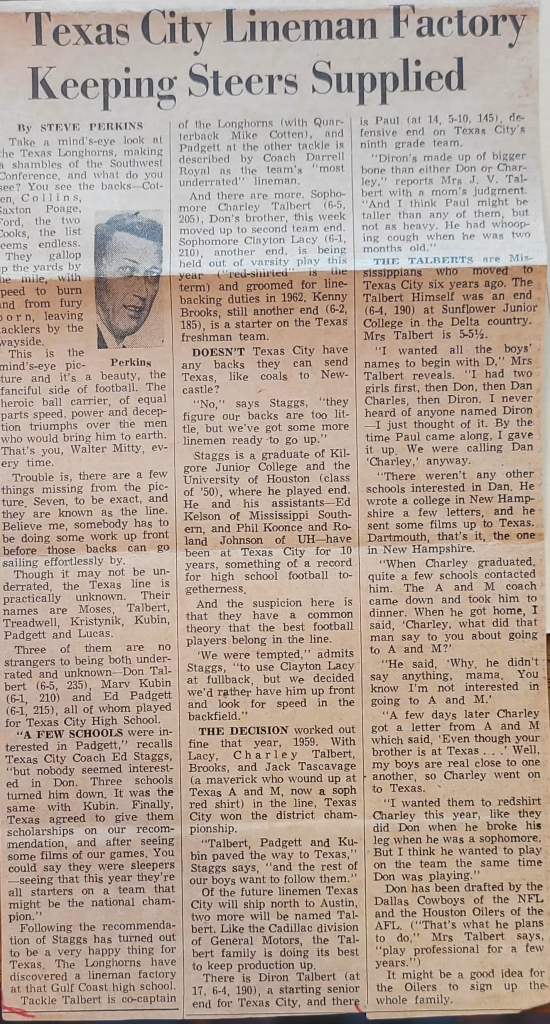

THE VARMINT BROTHERS.

Don, Charlie, and Diron Talbert Are Legends In Texas Football. Their reputation Is So Pronounced That A Pub In Austin Had A Sign That Said, “No Shoes, No Shirts, and No Talbert’s.” Hills Cafe had a sign that said “No dogs, no cats. No Talbert’s.”

The Talberts, all three in the Hall of Honor, were infamous, notorious, and rowdy, playing football games or raising hell on campus.

Assistant Athletic Director Bill Ellington told future Longhorn troublemakers, “Son, if you’re here to set a record for troublemaking, you might as well give up that quest right now. Because …you could start today and try your hardest every day to get into as much trouble as possible, but you would still never catch up with the Talbert’s.”

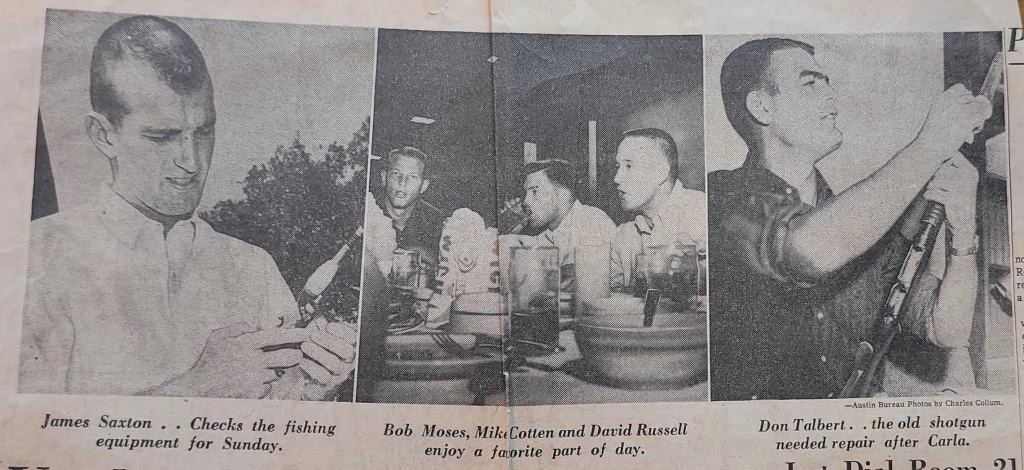

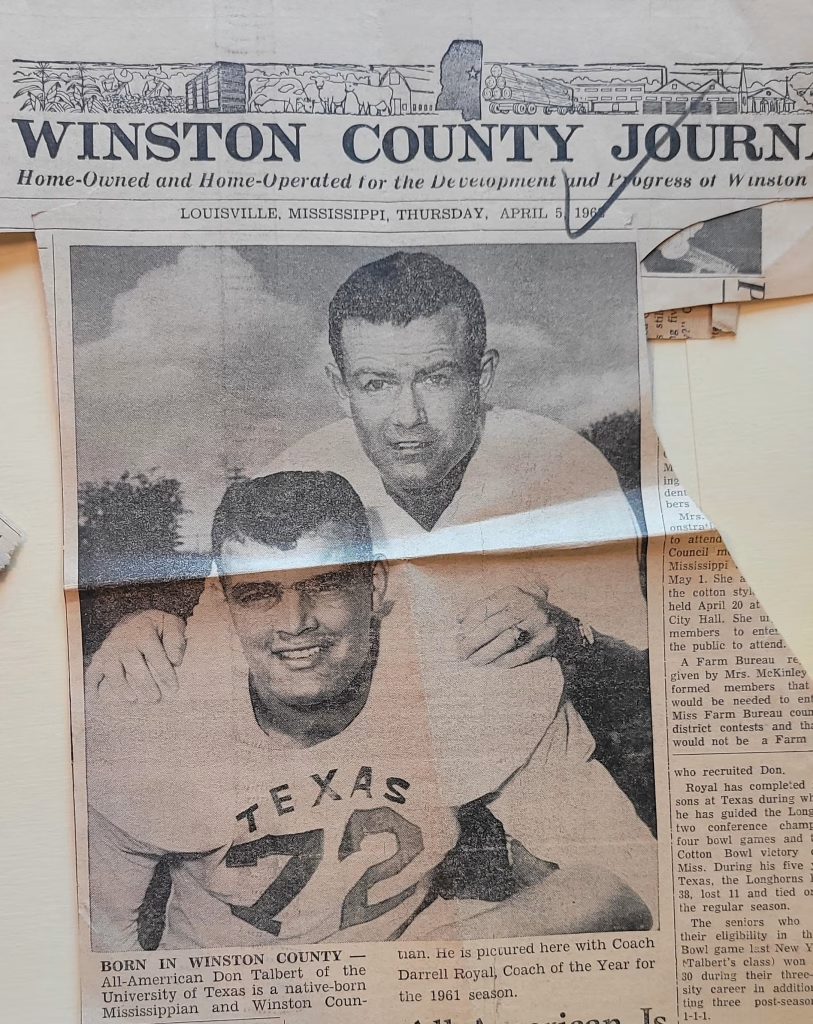

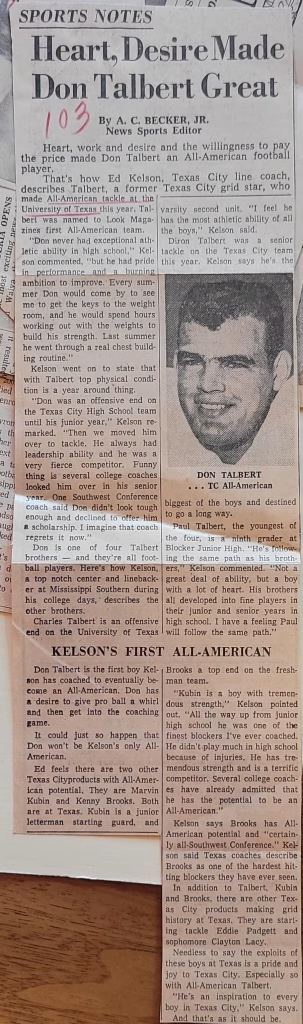

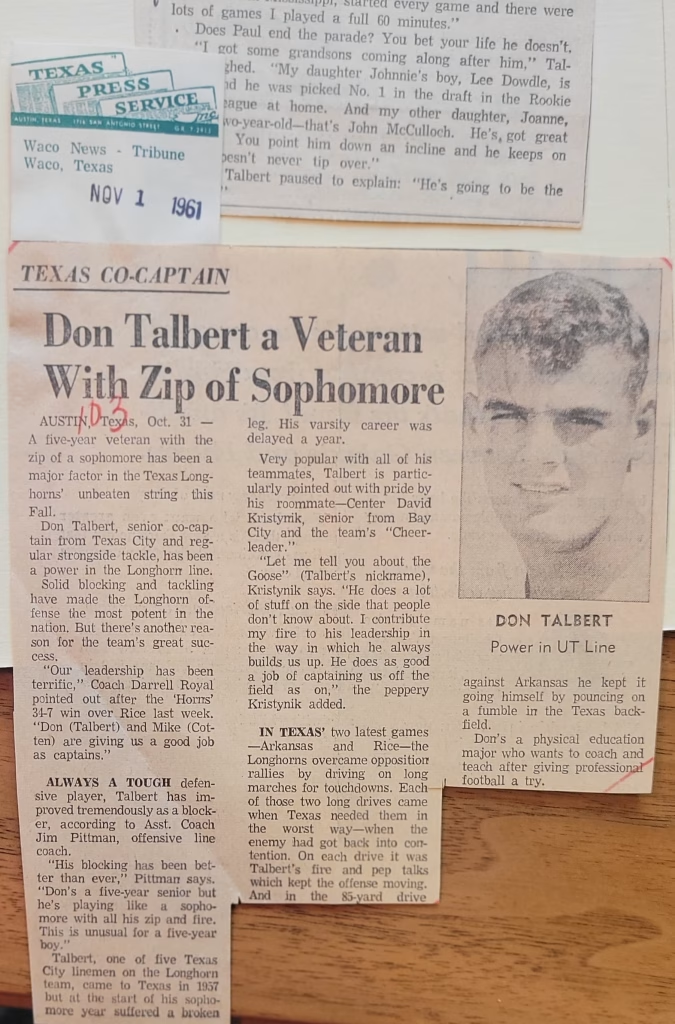

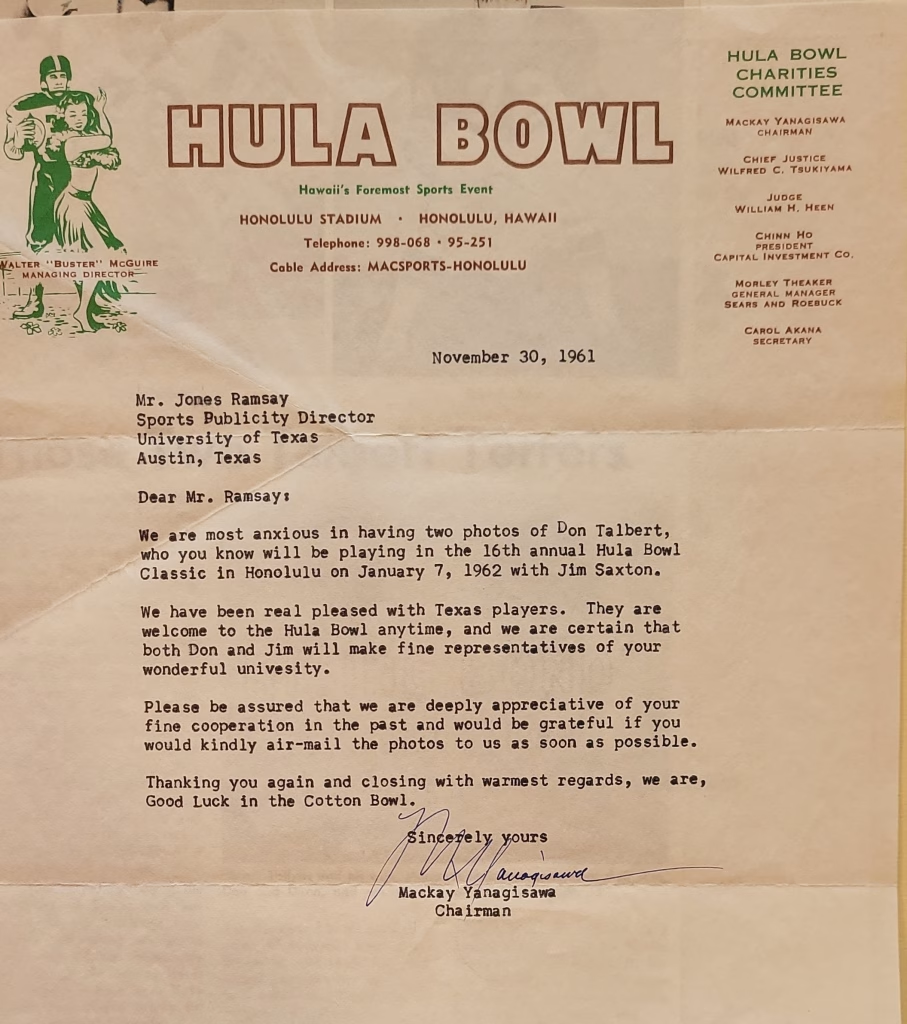

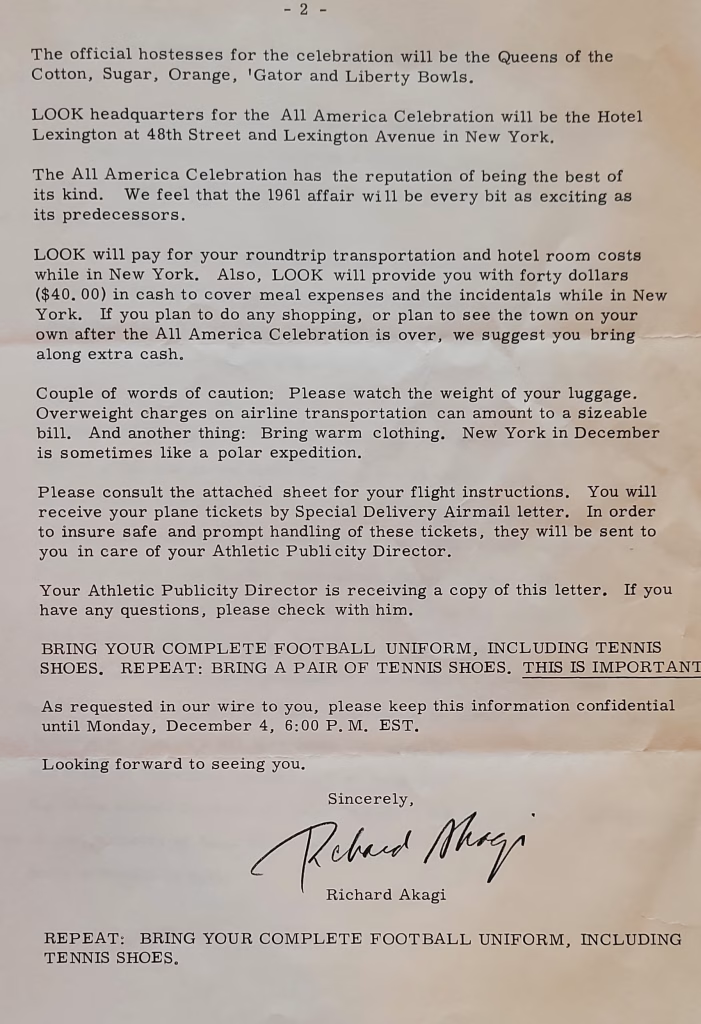

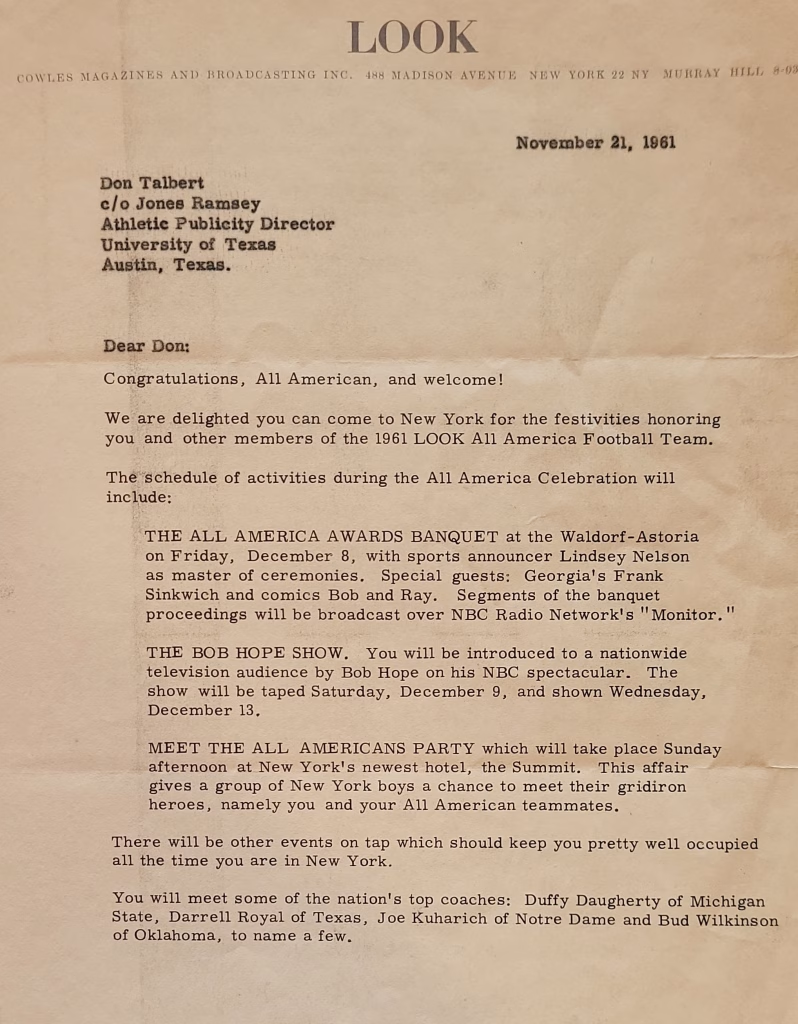

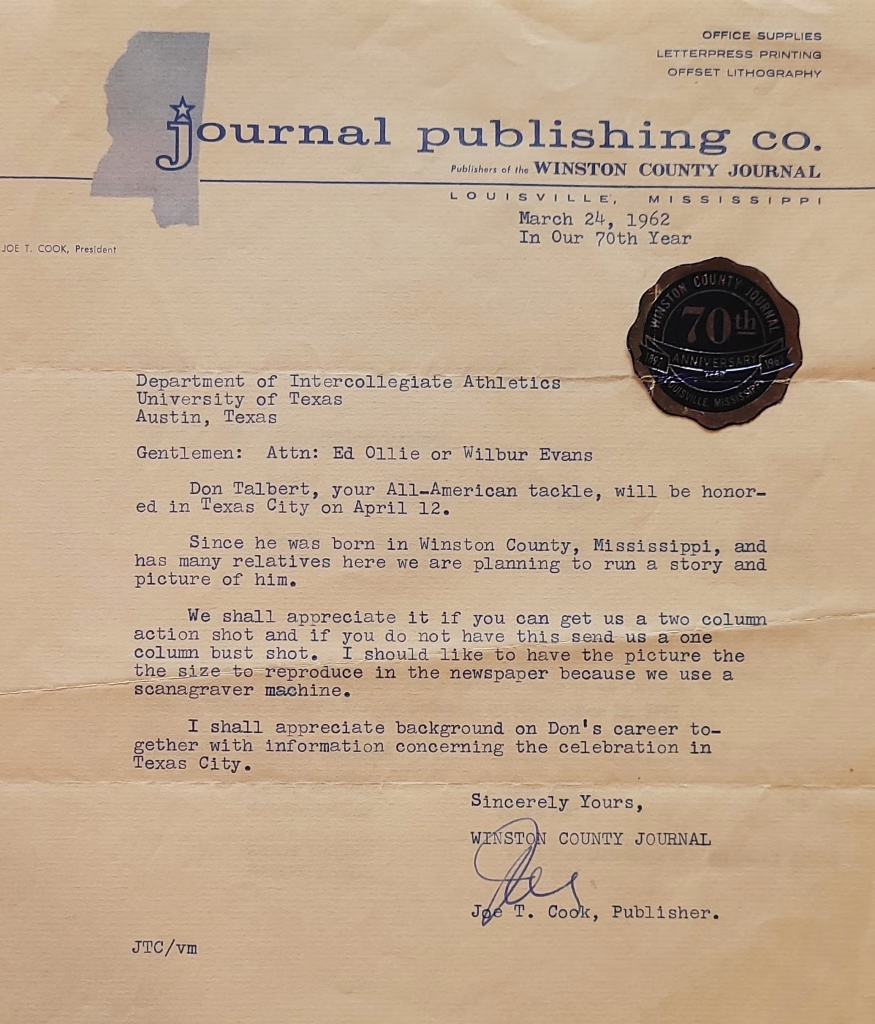

Don Talbert (1959- 1961)

Don Talbert (born March 1, 1939) was an All-American for the Texas Longhorns. He played professionally for the Dallas Cowboys, Atlanta Falcons, and New Orleans Saints. There are many hilarious stories about these three Longhorn characters. Still, since I have not received anything in writing from a teammate to confirm some of these stories, I will state that these three brothers forever changed the “dynamics” of Texas Longhorn football. Don Talbert and Joe Jamail 2015 Perhaps sometime in the future, some of their teammates will share some of the cleaner stories of the Talberts. .

In 1971, Don Talbert replaced Ralph Neely in the starting lineup. He was part of the Dallas Cowboys’ Super Bowl VI-winning team and was inducted into the Longhorn Hall of Honor in 1992.

Perhaps sometime in the future some of their teammates will share some of the cleaner stories of these great football players.

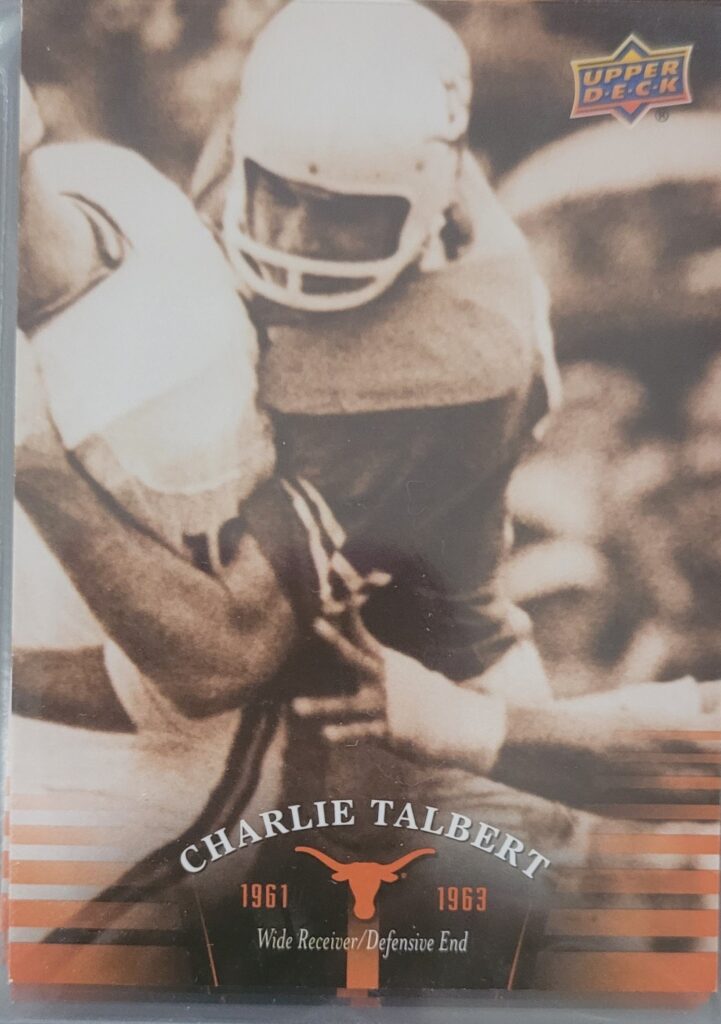

Charlie Talbert (“the modest one”- A Portion Of An Article Found On Texassports.Com About Charlie Talbert’s Induction Into HOH Is Below.

http://www.texassports.com/news/2013/8/27/FB_0827134627.aspx

Charlie Talbert – 1960

Longhorn Legends: Football Hall of Honor inductee Charlie Talbert

For a modest person who constantly played for the team and not for the individual accolades, Charlie Talbert was taken aback to hear about his selection into the Longhorn Hall of Honor.

“It is something that was unexpected,” Talbert explained. “I expected that winning the National Championship my senior year was all the recognition I needed. It is just an honor, and I am flattered to be selected into the Hall.”

Talbert is one of seven former athletes who will be inducted into the Texas Athletics’ Longhorn Hall of Honor this year for his contribution to the 1963 National Championship team and his performance on the field.

“Charlie was always great, never was in trouble of any kind, and he represented us with pride,”; commented David McWilliams, Talbert’s teammate on the ’63 squad and a former UT head coach. “When he graduated, he continued to give back to the program.”

Talbert will be joining his older brother, Don, and younger brother, Diron, in the Hall.

During a time when the forward pass was not often utilized, Talbert led the 1963 National Championship squad with 14 receptions for 188 yards and one touchdown. During the last regular season outing, Talbert caught three passes on the final Texas drive to help set up a score and seal the come-from-behind victory against Texas A&M.

He also played on the other side of the ball, serving as a defensive end. During his career, he intercepted a pass and scored a touchdown.

“The thing I remember about Charlie was how tall and skinny he was,” McWilliams recalled. “Coach put some weight on him, but the first thing you knew when you went out to practice was that he was tougher than anyone else on the field.”

“During my era, you had 11 starters that had to play seven minutes straight on offense, defense, and on special teams,” Charlie stated. “It was tiring and extremely tough during practice when you had to learn multiple positions.”

However, Charlie Talbert was not bothered by taking on such a feat. In addition to studying the football playbook, Talbert excelled in the classroom and was selected to the Southwest Conference all-academic team during his senior year.

“Coach [Darrell] Royal didn’t have to worry if Charlie was going to be around because he took care of business in the classroom and on the field,” McWilliams remarked. “That was Coach Royal’s number one thing – if you don’t take care of your business in the classroom, he wasn’t going to play you.”

photo 2022 – the Talberts are the three tall ones on the right at the Houston Touchdown Club.

After finishing his football career and graduating with a business degree, Charlie Talbert enrolled in the University of Texas Law School and earned his second degree. Upon graduation, Talbert attended the Naval Officer’s Academy and joined the Navy for three years.

After leaving the Navy, Talbert moved to Houston and became involved in the real estate business. He has been developing hotels in Houston and Austin since 1980.

As a grateful and proud member of the 2007 inducting class, Talbert credits all of his teammates and coaches for his selection.

“I have been away from the University of Texas for over 40 years now, and I always say that my team in my era all deserve to be inducted into the Hall of Honor,” Talbert said. “I was not an All-American performer and I was basically a team person, so I am extremely flattered and humbled by being selected.”

A link to Charlie’s memories about the 1963 National Championship team is captured in the link below

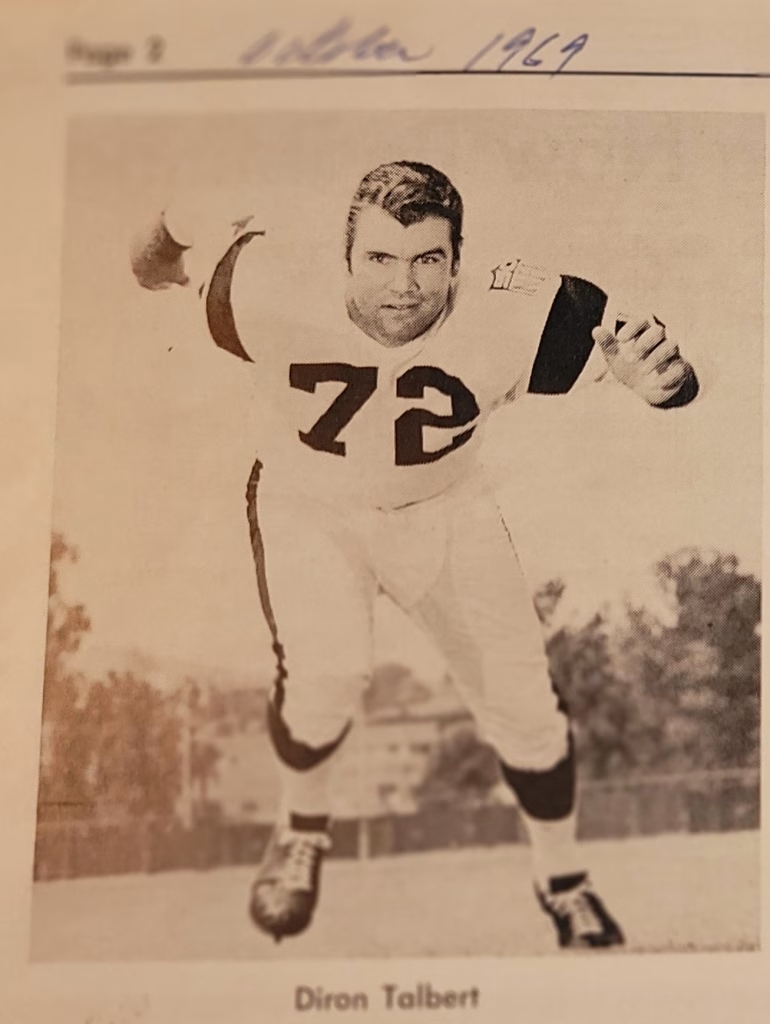

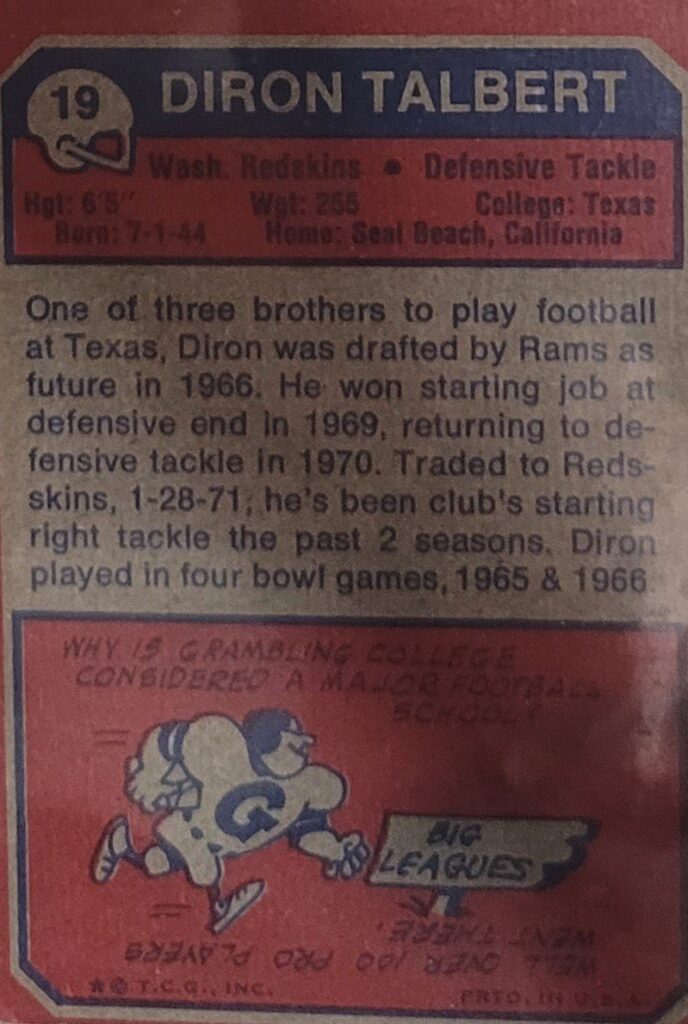

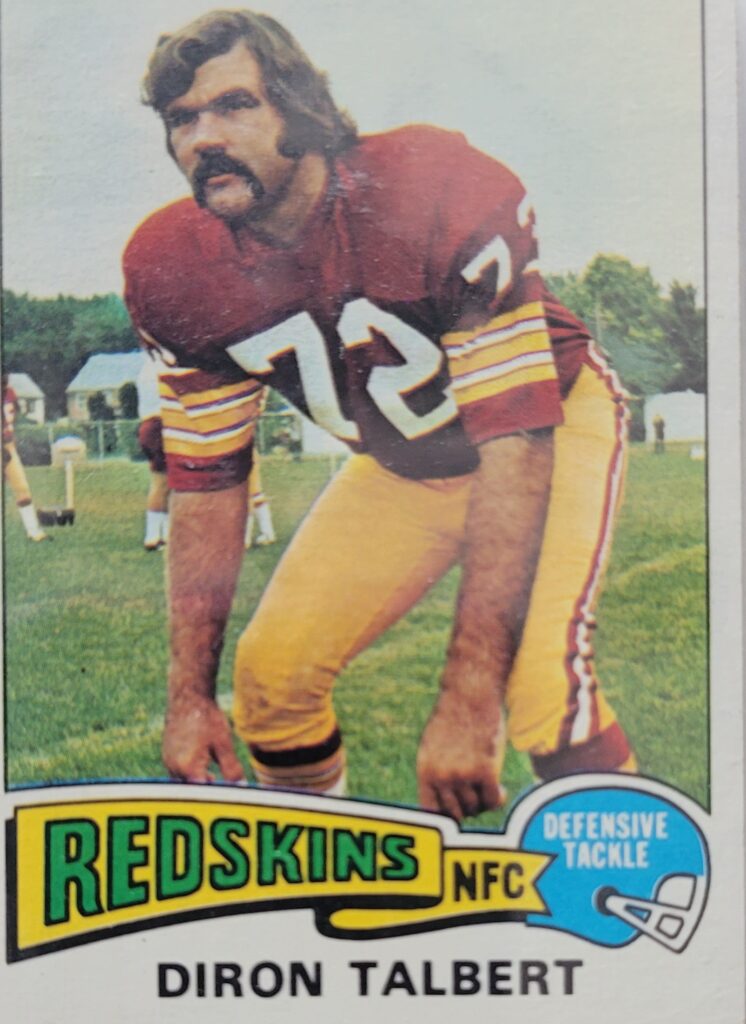

Diron Talbert Played Ball At UT, And He Was Inducted Into The Longhorn Hall Of Honor In 2005

Diron Talbert- Redskin

Diron played for the Los Angeles Rams from 1967 to 1970. In 1971 he played defensive tackle for the Washington Redskins until his retirement in 1980. It was during this period that Diron Talbert played an exciting, sometimes provocative role as part of the long-standing 1970’s rivalry between the Redskins and the Dallas Cowboys.

Mike Campbell

Diron Talbert was a key member of 1972 NFC Championship team. He played for 14 NFL seasons for a total of 186 games.

Diron’s College Priorities

Diron Talbert was very close to Defensive Coordinator Coach Campbell’s family. Close enough for Mrs. Campbell to call Diron and tell him that her son (Mike) was having an appendicitis attack and to take him from Moore-Hill Hall to the Health Center.

Unfortunately, on the way to the Health Center, a good-looking girl gets Diron’s attention, and Diron asks Mike to get out of the car. Mike has to walk the last part of the trip. I don’t believe that Mrs. Campbell was ever told this story.