1973 – Cotton Bowl- Alabama and Texas

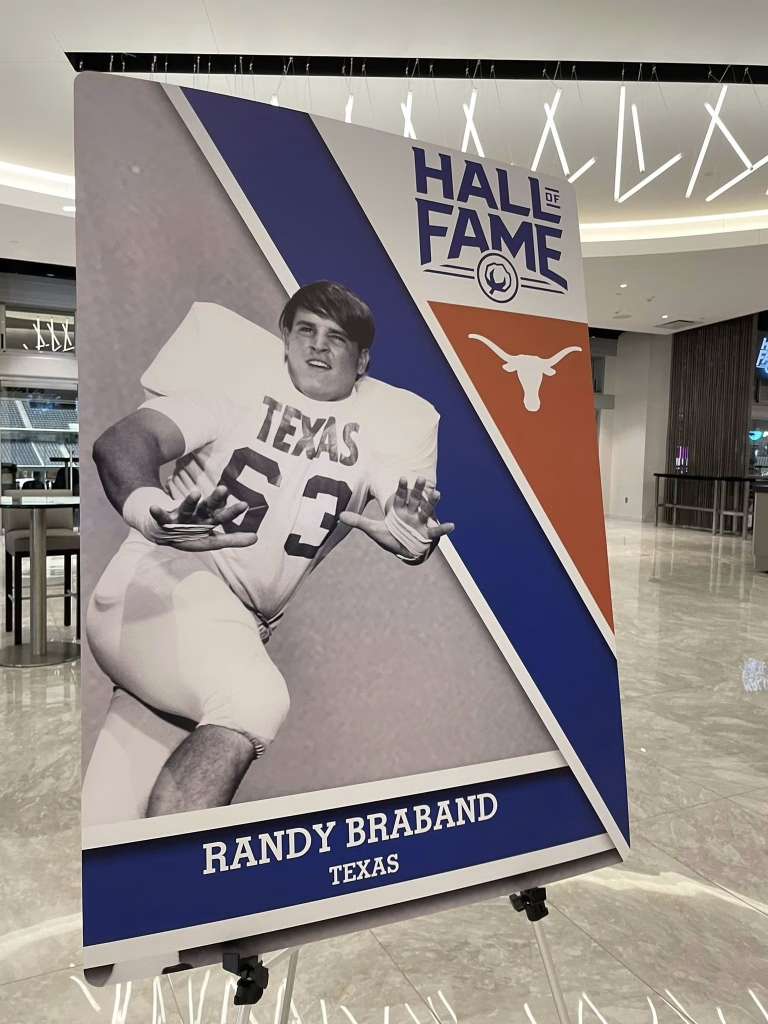

Randy Braband: Turning The Tide, Melting M&M’s

by Larry Carlson https://texaslsn.org

Randy Braband’s car had dodged a bullet, so to speak.

During a heavy overnight June rain, a hefty limb from a San Saba pecan tree in his front yard had landed in the driveway, just missing the vehicle.

I rode shotgun with Jay Arnold this drizzly morning. We motored up Highway 281 past Blanco and Johnson City to Round Mountain, then over to Llano, Cherokee and into San Saba, a speck on your map of westernmost Central Texas. It’s the birthplace of actor Tommy Lee Jones and the self-proclaimed “Pecan Capital of the World.” Uncle JW owned the barber shop on the courthouse square when I was a kid, and Uncle Johnnie B owned a cafe. My buddy Jay had been wanting to introduce me to his pal and Longhorn teammate of long ago and had asked Randy how much notice he’d need if we ever decided to cruise up for lunch. “Just gimme fifteen minutes,” had been Braband’s reply. So now, consent granted a week earlier, we were knocking on the front door.

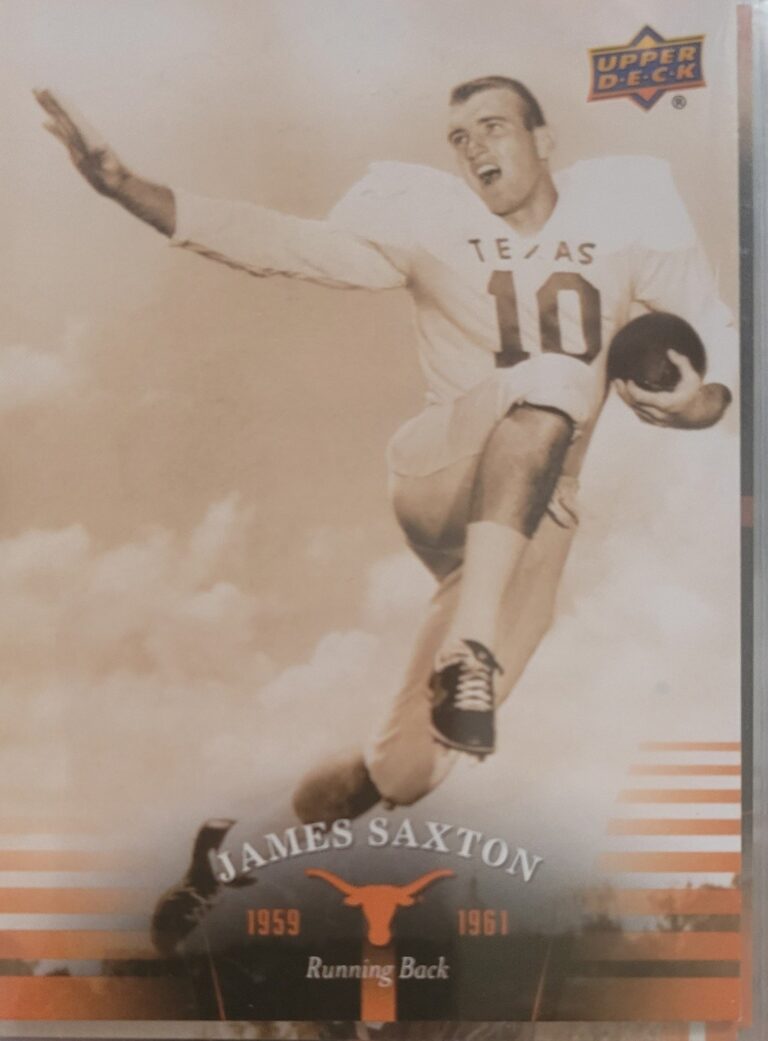

Time for a quick metaphor. More than fifty years after his last game for Alabama, Wilbur Jackson still owns the Crimson Tide record for career yards per carry, an impressive seven-point-two.

But in the closing moments of the Cotton Bowl on New Year’s Day 1973, the future first-round NFL draft pick couldn’t dodge Randy Braband on fourth-and-inches. In this case, Jackson was the tree branch in search of doing damage. Braband, number 63 in Texas burnt orange, on the last snap of his excellent Longhorn career, was the driveway. Splat.

That game, a 17-13 UT triumph and Darrell Royal’s final Cotton Bowl victory, ended a moment later, Texas able to run out the clock on Bear Bryant’s team to cap a 10-1 season for the Horns.

***

Randy Braband was inducted into The Cotton Bowl Hall of Fame’s 2025 class in May, along with the likes of Bo Jackson, Jerome Bettis and DeMeco Ryans. And on this soggy day in San Saba, Braband sported a CBHOF golf shirt, shorts, well-seasoned moccasins and a “Spring Woods Alumni Scholarship Golf Tournament” cap.

Fellow Spring Woods alumnus Roger Clemens did alright but he ain’t in the Cotton Bowl Hall. Never even made All-Conference at Texas. Braband did. Twice.

Along with former teammates Steve Worster, Cotton Speyrer and Mike Dean, Braband is one of the rare Cotton Bowl HOF members to have played in three Cotton Bowl classics. They performed during a stretch in which Longhorn football teams won the Southwest Conference and earned the prestigious Cotton invitation each season from 1968-1973.

As we drove around San Saba — it doesn’t take long but Randy wanted to check some of the surrounding roads for rain amounts and plant growth — Randy said he had truly enjoyed the three days of festivities leading up to the induction ceremonies. He told us he hung out mostly with Tony Davis, the former Nebraska running back and new inductee, and cited another inductee, Cotton Bowl Historian Charlie Fiss, for his kindness and congenial manner.

Braband, by the way, was hardly Mr. Congeniality when it came to foes from 1970-72. As a major contributor on the ’70 national champs and ringleader of the ’71 and ’72 SWC titleists, the intense middle linebacker racked up more than 200 career tackles. The Bama game, and the standing up of Jackson, served as a showcase finale. Braband had nineteen tackles versus the Tide.

As we pulled into the parking lot at Casa Del Charro for lunch, I asked Randy about some of his favorite Cotton Bowl moments, in addition to the “Wil-buuurrrr” felling. “Brad Sham asked me the same thing,” he responded, referring to the Voice of the Cowboys and the Cotton Bowl Hall of Fame master of ceremonies. “I’d say it was finally getting to eat a Fletcher’s Corny Dog,” he cracked, name-checking every State Fair-goer’s favorite artery clogger.

Randy, like Jay, is a loquacious sort, witty and colorful. He can tell some stories. Most, though, aren’t about football. He’d prefer to expound on the tomatoes he grows (and curse the fact that the wayward pecan limb did manage to clip a few plants), wax poetic about fig trees, elephant ears, date palms and verbena, and even toss out some scientific theories about how meteors and asteroids might have played a role in the formation of springs — way back in the Cretaceous Period of the Mesozoic Era — at Mill Pond Park, San Saba’s leafy public retreat from summer heat.

When I bring up a few more topics from his UT football days, Randy smiles broadly about recollections of swimming pool volleyball and swarms of girls over at Worster’s apartment, about good times in his own summer days as a page at the Texas Capitol and about an unlikely pal, Frank Erwin, Jr.

Seems that Erwin, the powerful, sometimes controversial, larger than life character who served on and chaired the UT Board of Regents, occasionally enjoyed getting to know and pal around with some Longhorn players.

One dog day of summer, the story goes, Erwin was looking for a way to enliven a humdrum afternoon. Somebody bet him he couldn’t commandeer the university’s jet by 6 pm, fly it down to Galveston for some “bid-ness,” find time to dine at Gaido’s and make it back to Austin by 11:30. Braband recalls Erwin quickly arranging to reserve the jet, making plans to meet a UT Medical Branch (Galveston) bigwig and getting the party started. Randy even got to bring along the girl he was dating at the time. The seafood, as it always is, was delicious at Gaido’s (Since 1911, as every good Texan knows). “My girlfriend and I even had a little time to walk on the seawall,” Randy laughed.

And you used to wonder how writers such as Dan Jenkins conjured up colorful stories for classics like “Semi-Tough.”

The Professor with Mountains in the background.

After lunch, Jay, Randy and I stood in the shade out by the big fallen limb, Randy still telling stories while checking his beloved tomato plants. Then a neighbor, nice fella who had attended Texas Tech, bless his heart, came over with an offer to get out the chainsaw and clean up the fallen branch. Braband said “hell, yeah,” or something to that effect but did want to tell uno mas tale. About football, actually.

It dated back to 1972 and the defensive huddle against SMU in Austin. Texas, 5-1, ranked ninth, was hosting a Mustang team, 4-2, that featured a speedy pair of running backs. Alvin Maxson and Wayne Morris, the M&M Boys, as they were billed, had homerun capabilities.

When SMU looked dangerously close to scoring a second touchdown (UT’s defense had not allowed any foe in ’72 to score two TDs), sophomore tackle Doug English, according to Braband, became hyper-animated, hyper-worried and jumpy in the defensive huddle. Braband, calling the signals, squinted but couldn’t see around English, playing against his hometown school, to communicate with the sidelines. Perhaps it was the only time Randy got blocked all day. (Writer’s note: Check the stats and you’ll see Braband with eleven tackles, DE Jay Arnold with seven).

DKR and Doug English

After yelling — to no avail — to English to get out of his sightline to the sideline, Braband did what he had to. He head-slapped the 6-5, 250-pound pup out of his way, got the signals, and called ’em.

“English was so mad, he wanted to fight ME,” Randy laughed now, remembering a bowed-up young beast. “He had originally said he was signing with SMU before he changed his mind,” Braband said, “and he didn’t want to lose to those guys. I think English made the next four tackles in their backfield.”

Braband allows another laugh and maybe a hint of a smirk, remembering the headslap heard ’round the huddle.

“Doug grew up that day.”

And the Horns limited the M&M boys and company to a puny 2.2 yards per carry on 47 attempts. Texas prevailed, 17-9.

As English came of age, the Longhorn defense was already a collection of grown-up ballers.

The “D” never did allow more than one touchdown to any of its eleven opponents. It is one of the most impressive statistics in The History of Longhorn Sports. Even in the Horns lone loss, by a misleading 27-0 count against OU, Texas stood tall against a team that had torched UT for 48 in ’71. But a blocked punt for a TD and a fumble to the Sooners at the goal in the closing minutes provided two of three touchdowns.

That ’72 Texas “D,” undoubtedly one of UT’s greatest, featured numerous All-SWC players (either in ’72, ’73 or in both years) including Braband, Arnold, English, LB Glen Gaspard and ends Malcolm Minnick and Bill Rutherford.

1973 Glen Gaspard

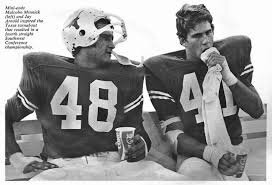

Jay Arnold, Malcolm Minnick is #48-

And now, long overdue, Randy Braband, the captain and bellcow of the crazy-good 1972 Longhorn stop ’em unit, has joined the immortals, etched forever into Cotton Bowl history.

Ask Randy what stood out most about the terrific three days that he and his guests were treated to in Dallas this spring, and he will tell you “all of it.” But one thing in particular made an impression. The tab for all the sumptuous food and fancy libations was picked up, of course. But Randy is still shaking his head over the price tag he noticed on one item. It was a cherry martini that his female guest enjoyed.

“That thing was 38 bucks,” Braband said, eyes widening.

But here’s the thing. Randy didn’t have to pay.

Unlike Wilbur Jackson on fourth and inches.

(TLSN’s Larry Carlson is a member of the Football Writers Association of America. He teaches sports media at Texas State University and lives in his hometown, San Antonio.)

1972 – Cotton Bowl- Alabama and Texas

COTTON BOWL FLASHBACK:

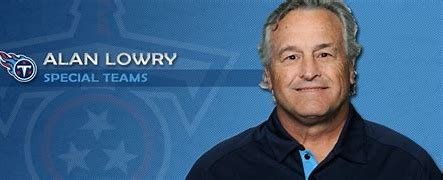

Alan Lowry And The Thin White Line

by Larry Carlson ( lc13@txstate.edu )

Written on December 15, 2022

A 1956 Western Union congratulations from Aggie Coach Bear Bryant to new Longhorn head coach Royal

Royal and The “Bear”

Alabama fans with elephant-like memories still believe Texas QB Alan Lowry was out of bounds on the winning touchdown run on New Year’s Day.

Fifty years ago, college football officiating crews did not spend thirty minutes during each game, reviewing plays and deciding whether or not to uphold or reverse calls made in real time, the whiz-bang way they went down. And for fifty years, Alabama fans with elephant-like memories still believe Texas QB Alan Lowry was out of bounds on the winning touchdown run on New Year’s Day.

It was football weather, 48 degrees, in Dallas for the Cotton Bowl game to cap the 1972 season.

Southern-fried football at its wishbone best was on the menu, with fourth-ranked Alabama and seventh-ranked Texas ready to rumble. Each team was 9-1, having won the SEC and SWC titles, respectively. UT’s lone loss had come in this same stadium, against Oklahoma in October. The Tide had been a prime national championship contender just one month earlier. But Auburn turned not one but two blocked punts into instant touchdowns in the nightmarish fourth quarter to stun Bama, 17-16, in the Iron Bowl rivalry matchup.

With teams led by college football’s two biggest marquee coaches — Bear Bryant and Darrell Royal — the Cotton Bowl would have another sellout crowd and a huge TV audience. The Tide had learned the wishbone extremely well, courtesy of DKR and his staff tutoring the Bear. He had visited Royal and Emory Bellard following the 1970 season and Bryant later hosted the UT duo in Tuscaloosa for higher education that led to Alabama’s super-successful switch to the triple option in ’71.

Royal’s team had just won its fifth-straight Southwest Conference title, its fifth consecutive ticket to the Cotton Bowl Classic. Texas sophomore fullback Roosevelt Leaks followed All-America tackle Jerry Sisemore in much the same manner that the Tide’s great Wilbur Jackson leaned on big John Hannah for running room.

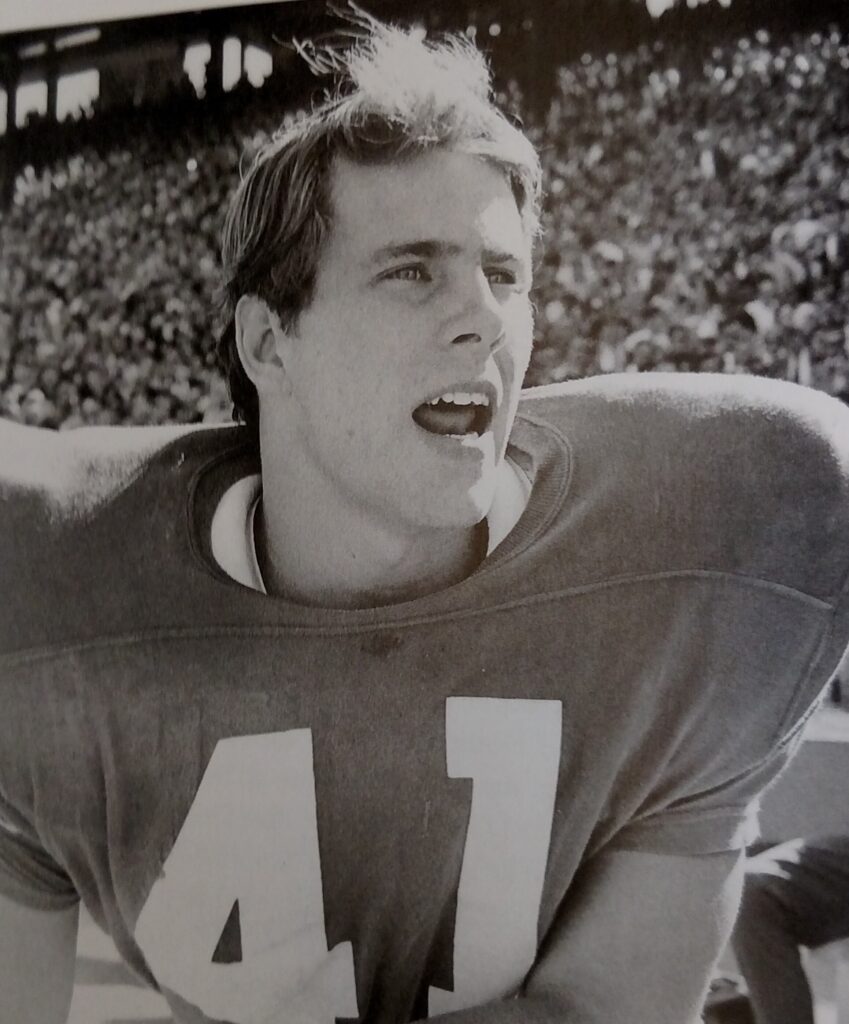

Alabama quickly built a 10-0 first quarter lead, converting two interceptions. Alan Lowry, UT’s All-SWC quarterback, just a year removed from all-conference status as a defensive back, had seldom thrown the ball all season. The Horns relied on the one-two ground game punch of Leaks and Lowry.

While millions of football fans were feeling a tad queasy on the day following New Year’s Eve revelry, Texas was fortunate to have Lowry even suited up. He had spent the previous day and night with a high fever.

“They had to keep changing the sheets because I was sweating ’em up so much,” Alan told me by phone from his home in Tennessee last year.

Texas got a Billy “Sure” Schott field goal in the second quarter after stalling at the Bama three but the Tide answered with their second FG and took a 13-3 lead to the locker room at halftime.

The second half would belong to the Burnt Orange. The magnificent Texas “D,” led by linebackers Randy Braband (19 total tackles) and Glen Gaspard along with rover Bruce Cannon, shut down Bama’s passing and successfully stymied Jackson on the ground. Port Arthur soph Terry Melancon picked off two passes and ripped a would-be TD away from a Bama receiver in the end zone.

The Leaks-and-Lowry show produced 120 yards by the former and 117 by the latter. After a three-yard Lowry TD in the third period, Texas still trailed, 13-10, with under five minutes to go. That’s when the play that still haunts Bama fans unfolded. On third-and-two from the Tide 34, Lowry faked to Leaks, then to RB Tommy Landry and took off on a wide arc down the left sideline, tip-toeing his way along the boundary, it seemed, and dashed in for UT’s first lead of the day. Television replays, then impotent as a force for reversal, hinted that the senior QB might have stepped out of bounds near the ten-yardline.

The Crimson Tide, suddenly trailing 17-13 and needing a touchdown to win, drove to the Longhorn 43 before Braband stonewalled Jackson on a do-or-die fourth and short.

Defensive end Jay Arnold fondly recalled Braband’s heroics just last week. “Randy was a steady, tough, durable linebacker who was at his finest when it was fourth down and one yard to go,” Arnold said.

“I always hoped they would run right at Randy in those situations because I knew the opposing team wouldn’t make it. Just like when he stuffed Wilbur Jackson.”

Randy Braband

Texas had won its third Cotton Bowl in five years, Royal’s final victory there. Lowry, a most resilient patient, was named the game’s Offensive MVP, and Braband took Defensive MVP honors. The Horns’ triumph lifted them to a number-three final ranking, the best since 1981, 2005, and 2009. They trailed only national champ USC and arch-rival OU.

Grousing by Bama fans who had watched on TV didn’t resonate with “the Bear,” who finished 0-3-1 against his good friend, DKR, despite his teams being favored in all four contests. “Texas deserved to win the game; they have a great team,” Bryant said.

He had displayed similar characteristics in the wake of a loss to Texas in the Orange Bowl following the ’64 season. Quarterback Joe Namath and Bama teammates thought Joe Willie had crossed the goal on fourth down before Tommy Nobis slammed the door on the team already crowned as national champs. “If you can’t score on four downs from the six…you don’t deserve to win,” shrugged the Tide’s immortal coach.

Lowry’s “wuzze in or wuzze out?” run quickly became the stuff of legends, even in its grainy film/pre-video era. One short production set the 34-yard run to Johnny Cash”s “I Walk The Line.”

But Lowry’s penchant for the big play had only begun.

In a coaching career that included five years (’77-’81) for Fred Akers at Texas and nine years as an assistant with the Dallas Cowboys, it was in the Oklahoma native’s (he was born in Miami, OK and grew up in Irving, TX) seventeen seasons with the Tennessee Titans that he earned immortality. Lowry is known as the Dr. Frankenstein who created “the Music City Miracle” that paved the way for the Titans to play in Super Bowl XXXIV.

January 2000 saw the Buffalo Bills take a 16-15 lead over Tennessee in Nashville, with just sixteen seconds to go. But the Titans made a successful handoff on the kickoff, then threw a long lateral pass and got a 75-yard streak to a, well, miraculous victory. Alan Lowry had done it again.

Fifty years later, some folks in the Yellowhammer State won’t budge on the contention that Alabama was robbed on Lowry’s tightrope act that chilly afternoon in Big D. But fifty years later, the Cotton Bowl score of 1-1-73 still reads:

Texas 17, Alabama 13.

Now 72, retired and enjoying grandkids in Franklin, TN, Alan Lowry continues to live large in Longhorn lore.