1901: The strange story of Kirksville’s ‘bone doctors’

1901: The strange story of Kirksville’s ‘bone doctors’

By Gaylon Krizak

“Quod ali cibus est aliis fuat acre venenum (What is food to one person may be bitter poison to others).” —Lucretius, “De Rerum Natura”.

The whispers started early in the season; before it had even begun, in fact, for many teams (eventual national champion Michigan, for example, was five days away from its season opener against Albion). Tucked well into “Gossip of the Gridiron” — a regular and vigilant syndicated college football notes column —in the Sept. 23, 1901, edition of the Lincoln (Neb.) Evening News was an item that began: “Next Friday the (Nebraska) team will leave for Kirksville, Mo., to play the Osteopaths there. It is thought this will be one of the toughest proportions of the year. The doctors have been training since the middle of August under direction of Coach (Ernest C.) White, who made his reputation at Missouri in 1899. There are ugly rumors of professionalism in connection with this team.

No evidence was presented; no substantiation even hinted at. Yet, there it was in black and white: one of the many charges that forever dogged the team representing the American School of Osteopathy (ASO) of Kirksville, Mo., which in three short years had gone from a school with no football team to a Midwestern powerhouse. How? Depends on who was telling the story. Out of nowhere There was no NCAA in 1901. College athletics, rigorously championing a strict amateur code, had no real self-policing mechanism past the honor system. Consequently, countless stories exist of players enrolling for the semester a sport was in session, then vanishing the moment that season was done.A magazine devoted to “Northeast Missouri history and folklore,”

The Chariton Collector,framed the era this way in a Spring 1984 history of Kirksville’s “‘O’ Men”: “At this time there were no set rules to keep a team from cancelling a previously arranged game to play someone else, or just not to play at all. Other rules, such as a player’s right to play, the length of games, the size of the field, specific rules, and other decisions were argued before each contest.

An athlete could play four years at an undergraduate college before coming to ASO, and then could continue to play as long as he studied osteopathy at ASO.” That last sentence was the key to Kirksville’s argument, as well as its success. Three days after the first “Gossip of the Gridiron” accusation ran, another item appeared featuring Dean Charles M. Laughlin’s rebuttal, which read in part: “Athletes here are under the control of the faculty and no professionalism is allowed. We stick strictly to the amateur rule. To my personal knowledge, all members of our football team are regular members of the school and do not belong in any sense of the word to the professional class.” Kirksville “became a well-respected school” because of its gridiron prowess, the Chariton Collector piece hypothesized. It described the ’01 team this way: “Some of the players of the early teams were so big that they organized their own club known as the Osteopathic Beef Trust.”

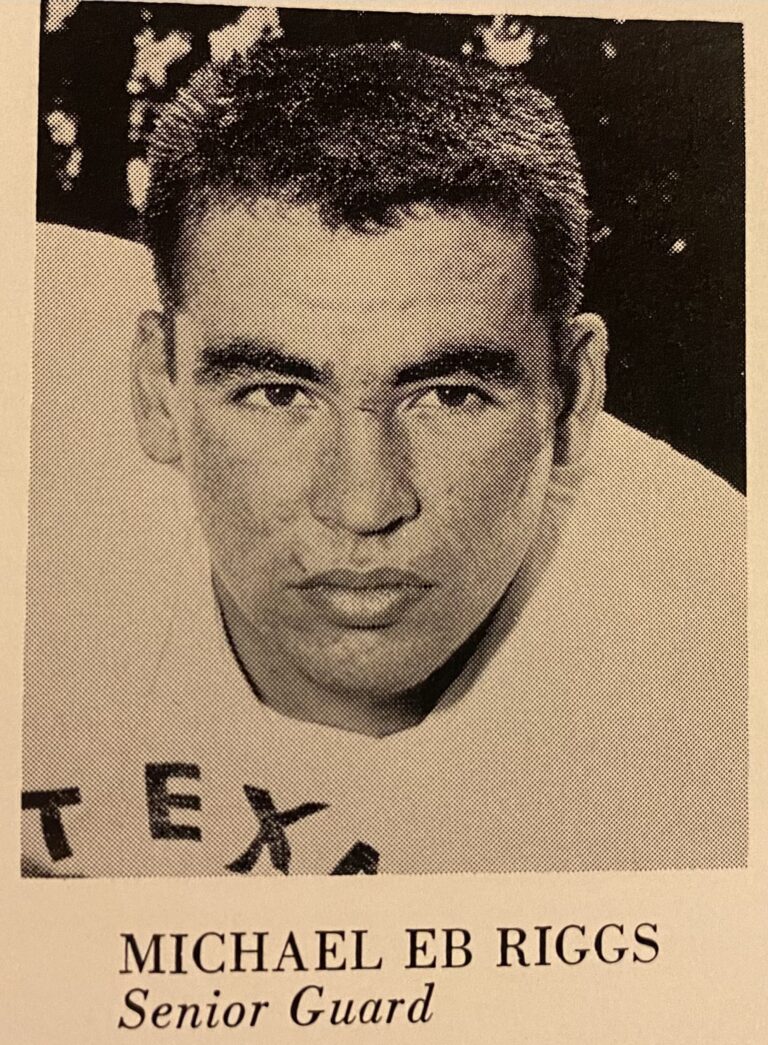

After a 3-3 start that included losses to regional heavyweights Nebraska (5-0), Kansas (17-6) and the Haskell Indian Institute (36-6), as well as a 22-5 revenge victory over Missouri, the Osteopathic Beef Trust went on a tear. Kirksville rolled to seven consecutive victories in which it shut out six opponents (allowing 6 points to Christian Brothers, Mo.) and averaged more than 38 points per game, a huge number in the iron-man, pre-forward pass era. To be sure, the opponents included the Gem City Business College, Tarkio, Ottawa (Kansas, not Canada) and Highland Park (Iowa, not suburban Dallas). But there was one big fish among the small fry, and it was with that victory that the trouble really started.

Messin’ with Texas

As the Osteopaths’ record improved, their reputation plummeted. The discord reached a head when Kirksville hosted Texas on Nov. 19. The Longhorns were playing the second of four games in what then was labeled a “northern trip.” Befitting the era, those four games were played in a span of nine days, with the visit to Kirksville coming three days after an 11-0 win at Missouri that improved UT’s record to 6-0-1.To put it mildly, the Osteopaths were anything but generous hosts, except in one regard: With the score 48-0 midway through the second half, White agreed to Texas coach Huston Thompson’s request to end the game early. Kirksville’s hurry-up style had run the ’Horns ragged; the halftime score was 36-0, with the home team five yards away from another touchdown when the half ended. Only two penalties were called in the game, neither of which was for holding. Odd, since Kirksville reportedly had been flagged for holding 12 times in one half while nipping Christian Brothers 11-6 in a tune-up for the Texas game. But little was thought of it at the time.

Instead, the Longhorns’ immediate wrath was aimed at the Kirksville students and fans. As described by Lou Maysel in his 1970 book, “Here Come the Texas Longhorns,” the Texas team boarded the train that eventually took it to Lawrence, Kan., for its next game four days later. The Longhorns, however, “found all the seats on the special coach filled with Kirksville students. They remained in their seats for the 50-mile ride to Moberly, Missouri, forcing the Texas team to stand the entire distance.”

Were the Osteopaths out of line, or were they just operating under the standards of the day in that way, too? The Chariton Collector retrospective described a scene from earlier in the ’01 season: “(The 1901 Missouri State Football Championship) and the win over Missouri were especially sweet. The previous year a trainload of about 225 supporters left for Columbia. The train, which was four cars long, was covered with the school colors of red and black.

After ASO lost 13-0, Missouri fans rushed the train and tore down the banners, carrying them triumphantly through the city streets. They also proceeded to take personal belongings of the ASO crew such as canes, hats, and trophies. As the students of ASO resisted, a general riot followed and several people were injured on both sides. During a short layover in Moberly, the engineer of the train was given an osteopathic treatment to calm his nerves and ease his tensions.

In the following days, Columbia newspapers apologized for the outrageous conduct of their fans.” No apology followed the Longhorns to Kansas. ‘Through with them’ . On Nov. 22, a day before Texas was to meet Kansas, UT athletics officials along for the trip made a stop in Kansas City. As dutifully reported in the next day’s edition of the Lincoln Evening News

— “Gossip of the Gridiron,” of course: “An impromptu meeting of the heads of athletics in Kansas, Missouri and Texas universities was held in Kansas City yesterday. It was the unanimous opinion that the Kirksville, Mo., osteopaths should be boycotted in the future. Nebraska will heartily endorse this movement and it is said Iowa will unite with Nebraska. The chief objection to the bone doctors is that they play rough, harsh football, and treat guests in an ungentlemanly manner….

”A chief source was listed as “Manager McMahon of Texas university.” This probably was team captain Marshall “Big” McMahon, since UT’s ’01 team manager was James Taylor. No matter. McMahon’s words packed far more of a wallop than the Longhorns’ on-field play had done just days earlier. McMahon claimed Kirksville had agreed upon using V.H. Bremner of Des Moines, Iowa, as an official, then reneged at game time even though UT had paid Bremner’s way to Missouri. “(Kirksville) threatened to declare the game off and deprive us of our $300 guarantee if we insisted on Bremner officiating,” McMahon said. Instead, he continued, the two coaches were used as officials.

“Then we got decidedly the worst of it,” the Evening News quoted McMahon as saying. “The crowd was so threatening that our coach did not dare to give us even what was coming to us, and once when a wrangle came up, the crowd surged into the field and threatened to mob us. On the other hand, White’s work was high handed robbery. His men were holding continually, but he could not see it, and to cap it all off he himself purposely got in the way of a play that robbed us of a chance for a touchdown, and when we protested said it was accidental.

“Texas, you bet, is through with them.”

Epilogue- A St. Louis Globe-Democrat report later confirmed the Lincoln paper’s list, saying Haskell also had joined Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, Iowa and UT in agreeing to boycott the Osteopaths, with each school reportedly leveling allegations similar to McMahon’s. ASO officials again denied any wrongdoing and said the boycott rumors were without substance. Only Haskell among those six schools ever played Kirksville again.

The Osteopaths finished the 1901 season 10-3, having outscored their opponents 359-69. And Kirksville for a couple of years found a decent supply of big-name opponents to replace the boycotters: Illinois in 1902-03, plus Wisconsin and Notre Dame in ’03. But its reputation continued to dog the program.

More than a decade after the fateful 1901 Texas-Kirksville game, UT coach Thompson (who left after the ’01 season, his second in Austin, with a 14-2-1 record) labeled the Osteopaths a team “composed of ringers from all over the country.”

The Chariton Collector piece obliquely referred to “some complications through the years” as the reason the Kirksville program went through 19 coaches in its 29-season history. After 1903, the big-name opponents were all but gone for good. Kirksville played TCU in 1920-21, but incomplete College Football Data Warehouse records indicate the program’s final quarter-century was otherwise spent taking on similarly small colleges from Missouri and surrounding states.

Since the end of the 1928 season, football fans have been deprived of such cheers as: “Oskie wow-wow! Skinny wow-wow! Osteopaths! Ribs raised, Bones set, We cure — you bet! Osteopaths!” Still, in many ways nothing needed more reconstruction than the school’s reputation. So, with football gone, the future physicians — befitting the proverb found in Luke 4:23 — healed themselves.

ASO eventually became the Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine (KCOM) as part of A.T. Still University. It is ranked by U.S. News and World Report as “one of the best medical schools in the country for rural and family medicine training.”

However loosely the term “student-athletes” fit the participants at the time, Kirksville for that can at least partially thank its early football teams: “At the turn of the century, ASO was a little-known school because the study of osteopathy was still relatively new,” the Chariton Collector piece concluded. “Athletics gave way to a stronger emphasis on study, and with the greatness of its athletic program, the emphasis on medical organization must also be as great. With the help of its intercollegiate sports program, ASO gained needed recognition. This, in turn, led to the development of ASO to KCOM and its respected reputation in medicine.”