Lemons vs Sutton ????

A battle between Abe and Eddie led to a tirade for the ages

ByLARRY CARLSON Jun 7, 2020

When Eddie Sutton passed away Memorial Day weekend he took an oversized piece of Longhorn sports lore with him.

Sutton, after a long, long wait, was elected to the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame’s 2020 class this spring. He was a figure both cussed and discussed for many decades across a hardwood history awash with victories, controversy and no small share of competitive arrogance.

At Arkansas, he helmed superlative players and teams at a time in the late ’70s and early ’80s when the Longhorns and Razorbacks emerged suddenly with one of the better rivalries in college basketball.

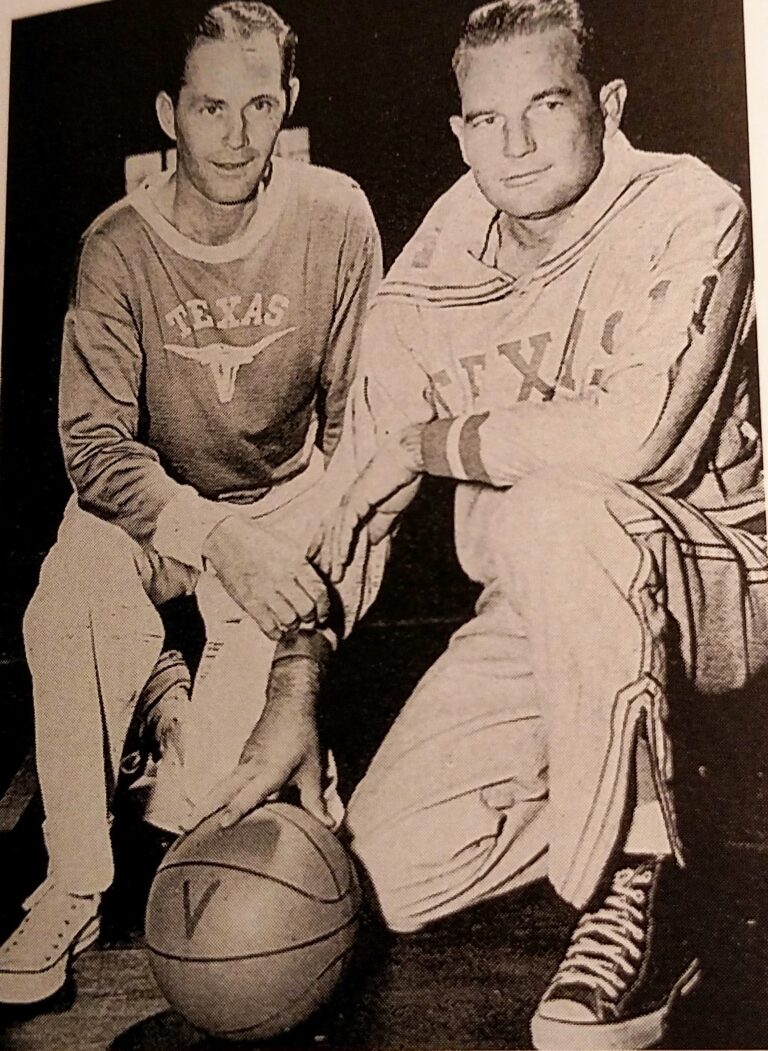

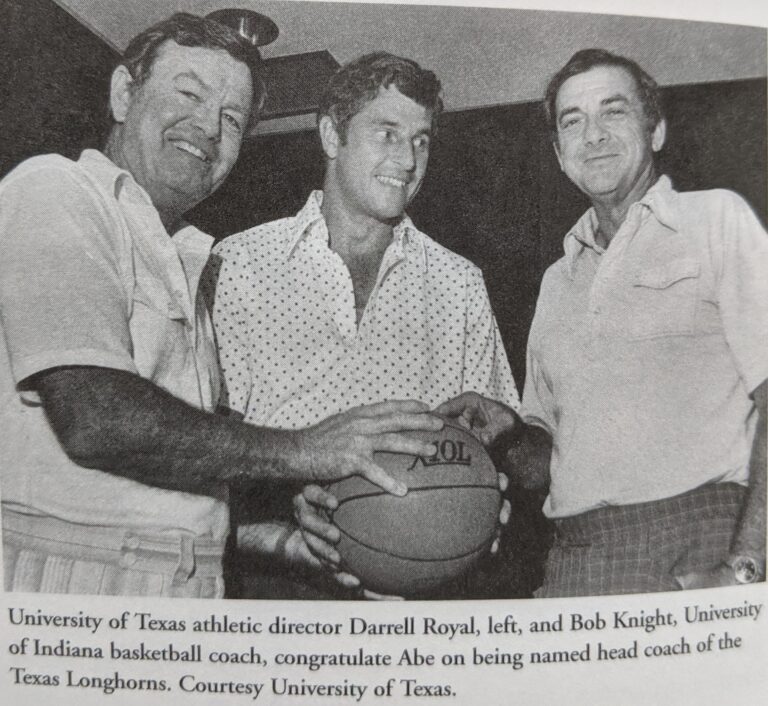

And Sutton brought out the best — and sometimes the worst — in his UT counterpart, the inimitable Abe Lemons.

Go to 9:00 mark for a short excerpt on the Lemons vs. Texas confrontation

One incident stands above all others from the series.

It was the all-time postgame tirade by a University of Texas coach. Maybe by any coach in any sport.

Coach Mike Gundy- The Mullet

Mike Gundy’s long ago “I’m a Man” rant hardly registers in comparison. Even though Oklahoma State’s Gundy does, indeed, have the dead eyes of a would-be serial killer, his laughable “I’m 40!” rant was less than manly, fired not at a combatant or an enemy fan base but at a female reporter who asked a legitimate question.

But when Lemons, known for homespun humor and wiseacre witticisms, went on a full-blast rant eons ago in Austin, he was doing some loud, full-speed railing against one of the winningest coaches in America, his arch-rival in the old Southwest Conference.

To put an exclamation point on the five-minute post-game soliloquy, he would sarcastically berate one of the game officials. It should have been an instant classic. Viral nirvana. But nobody had a cell phone handy.

It was early 1979, now more than 41 years ago.

“If (Sutton) ever says another [expletive] thing to one of my players, I’ll knock his ass off,” Lemons hissed to those of us in the media pool after the latest edition of a rousing battle between top-20 teams.

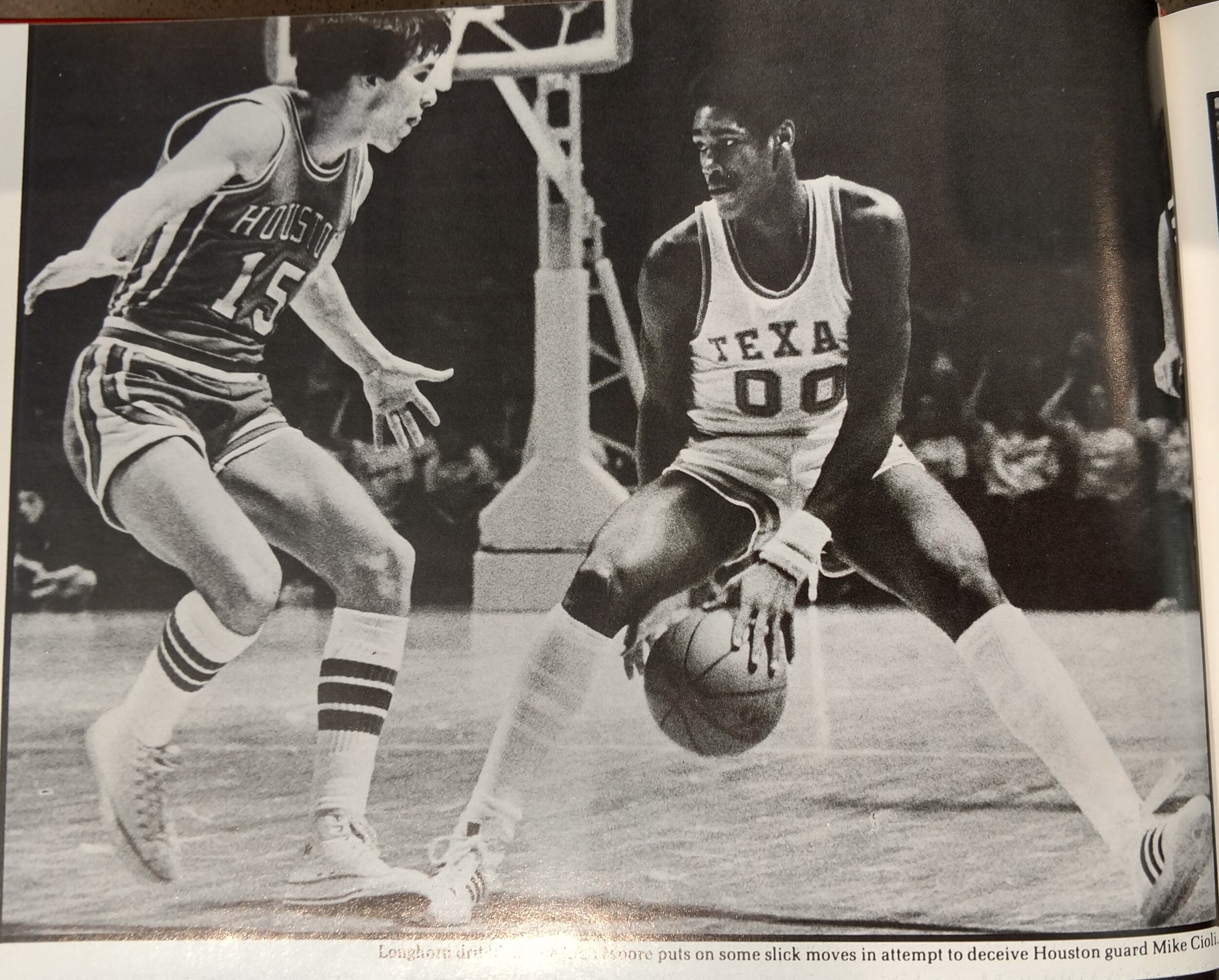

Lemons was referencing Sutton’s response to Texas guard John Moore’s attempt to draw a charge as the last few seconds of the half elapsed with the Hogs bringing the ball up near mid-court.

Sutton had said something to Moore as they left the floor.

The beginning of Lemons’ blistering verbal blast came barely an hour after Abe and Eddie had been restrained by their players from a potential fist-fight as the two top-20 teams headed for the locker rooms, a surprise gut-punch to everyone who saw it.

I had just popped up from the courtside media tables to stretch my legs and grab a Coke. What for the players and coaches should have been a brisk walk en route to some quick strategy adjustments had erupted into the sight of grown men in suits yelling at each other, then with arms flailing, immediately being held back by their startled assistants and young troops.

Lemons, 56, and Sutton, 42, had looked like a middle-aged mayhem version of a hyped-up weigh-in for a Vegas prizefight.

“He called (Moore) a dirty player and that’s not the way to play the game” Lemons vented in post-game remarks, voice rising and neck veins pulsating.

“That’s not his business.”

Then Abe recounted his version of a similar ploy by a Hog player a month earlier — in what would be a huge Longhorn victory over a top-10 team in hostile Fayetteville — that had apparently been condoned by Sutton.

When they do it, Abe complained, “that’s cute.”

Allow this writer a brief timeout.

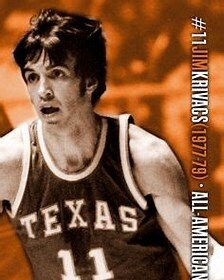

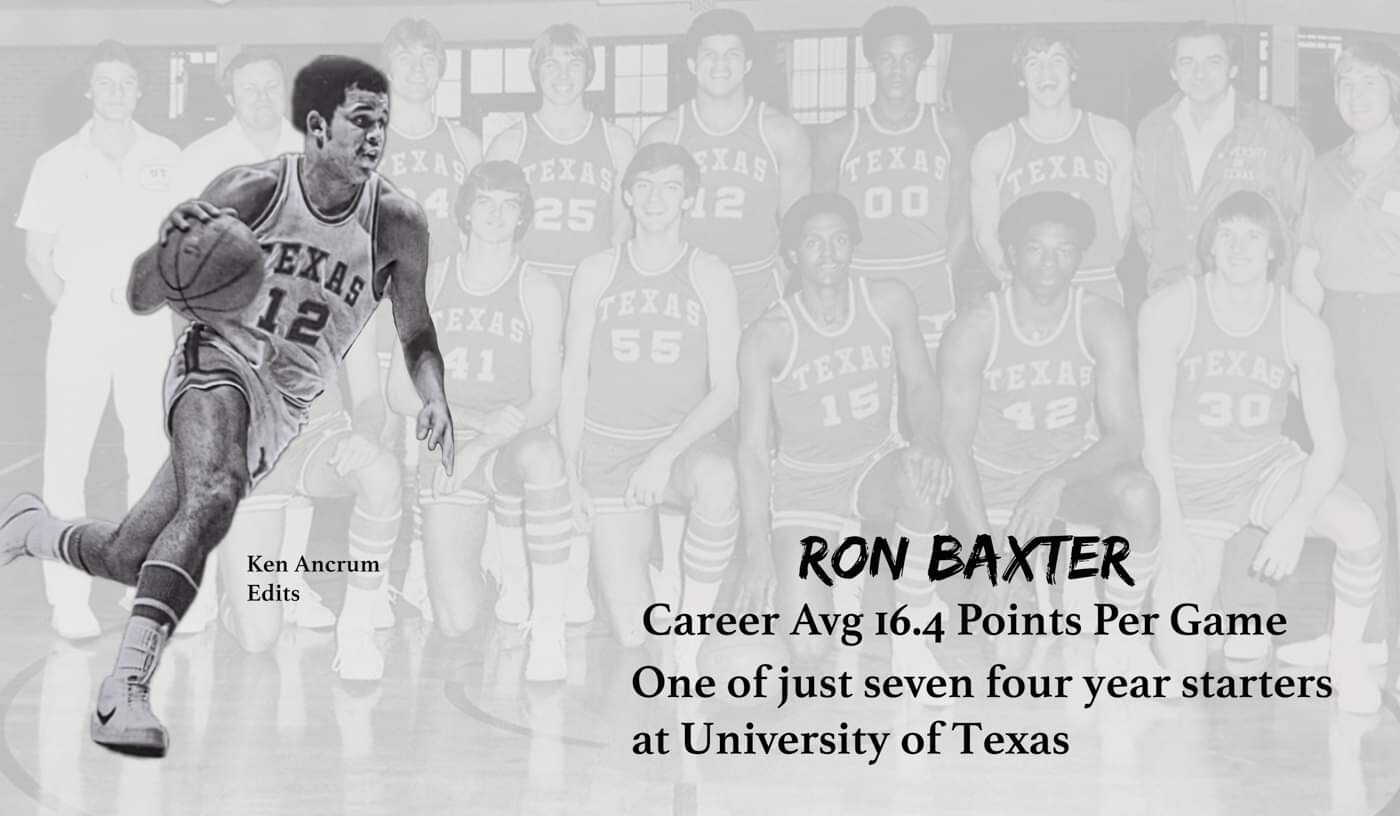

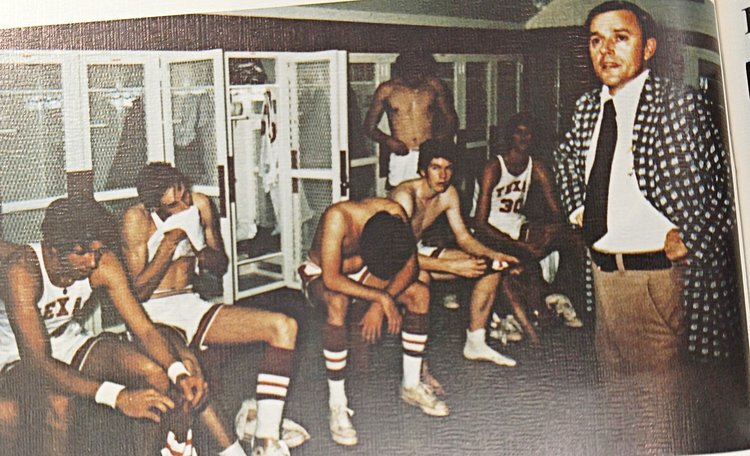

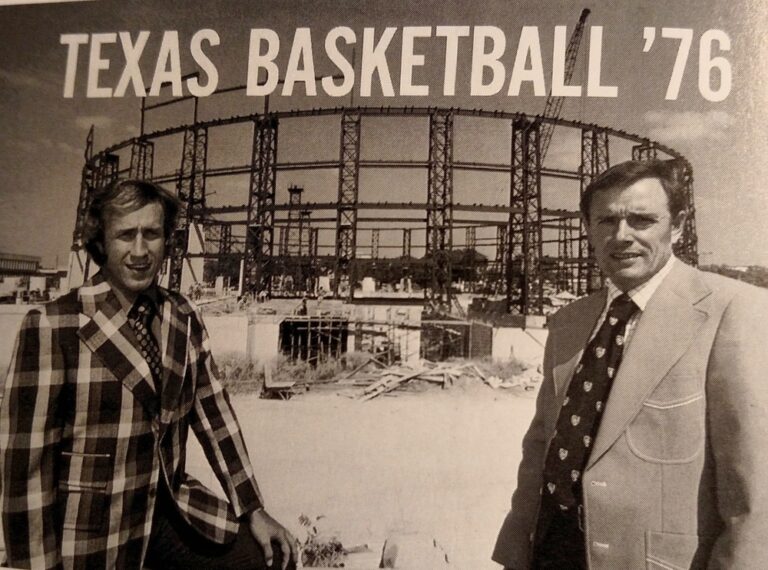

I was a 25-year-old sportscaster for Austin’s KVET radio, on the job for my second year. Covering every home game, I had not yet experienced a Texas basketball loss. Having opened the new Erwin center in the late autumn of ’77, Lemons’ Longhorns ticked off 24 straight wins at home over the span of almost two full seasons. Behind a plucky squad paced by Moore, sharpshooting Jim Krivacs and the redoubtable 6-foot-4-inch forward, Ron Baxter, UT’s prize accomplishments in that streak included the ’78 takedown of a Razorback machine that featured “the triplets” — Sidney Moncrief, Marvin Delph and Ron Brewer — who would lead the team to the Final Four that spring.

Through blowouts and narrow escapes, Texas had been invincible in the home that fans called “the Super Drum.”

In our postgame sessions with Abe, we had grown used to Abe’s victory cigars and his penchant for pontificating about a wide-ranging array of subjects, much like an early version of the quirky Mike Leach. Nobody really had to ask questions. Abe held court. We in the media just rolled tape or scribbled quickly, sometimes laughing with him. But he could be sour and surly, though he had always been victorious. Usually, he was good-natured, in a smartass way. Always, he was entertaining.

Abe was certainly sharp and on the attack, if looking weary, after the visiting Porkers pulled away and beat Lemons’ Longhorns, 68-58 on the first day of February 1979, ending the lengthy streak. His post-game analysis started with his reaction about Sutton’s exchange with Moore (The Arkansas coach shared with reporters that he only told Moore “he was too good of a player to be doing ‘that kind of thing'”).

“If (Sutton) ever says another [expletive] thing to my player, I’ll knock his ass off. And you can put that in the paper. If he EVER jumps on one of my players… I’ll liquidate his ass. And I’ve told him that,” Abe seethed.

“He’s a chicken [expletive]. And you can write that in there, too,” Lemons continued, rolling. “He’s got no cause to be talking about my player. If the referees can’t see it… what the hell is it to him?”

Then, in defense of his flinty players, came the chicken-fried verbal uppercut that stuck with everyone in the room.

“If he ever says another thing to ’em, I’ll tear his Sunday clothes.”

Most members of the media were now trembling with pent-up laughter. It was like the first time you heard your grandpa cussing a blue streak at a recalcitrant door hinge. Instead of bursting out in laughter, we stared at our shoes or notepads, microphones still going.

Abe had said his piece now, though, and knew his audience.

“Otherwise… it was a bad game, ” Lemons drawled, smirking. With the bomb now defused, everybody laughed.

“We didn’t play well anyway. When you play bad, you’re not supposed to win.”

Then Lemons basically shrugged off his first home loss in two seasons, noting that Texas had ended a home streak owned by Arkansas and now the Hogs had done the same to UT. And he said something that would prove prescient in another month when Texas and Arkansas would share a court again at the conference tourney.

Abe said his team could never allow the Razorbacks — still featuring Moncrief, now alongside a pair of Ozark Mountain peaks, 6-foot-11-inch center Steve Schall and 6-foot-10-inch forward Scott Hastings — to get ahead because then they could control the tempo against the undersized Bevos. Lemons reminded us that his bunch couldn’t play with, and beat, a deeper, more physical team if the officials stood by while Arkansas “was hanging on us.”

He directed his ire at a particularly laissez-faire ref he labeled “that little guy” by providing a brief lesson in economics.

“If that one guy was gettin’ $100 a toot for his whistle, the sumbitch couldn’t buy an all-day sucker.”

That was Abe’s last jab for the session. For the next few days, KVET Radio played my reports with plenty of bleeps to mark what wasn’t considered palatable for listeners, or deemed legal by the FCC. The major newspapers across Texas managed to give readers the general idea of what UT’s salty coach had spewed.

March came and the Horns and Hogs advanced to the SWC title game at The Summit in Houston, a rubber match guaranteeing the victor an automatic NCAA slot. Arkansas grabbed an early lead and made Lemons’s prophesy sting. Sutton’s team expertly froze the ball, giving Texas a precious few possessions while hogging the ball for minutes at a time, waiting for breakthrough lay-ups, tiring UT’s depth-strapped lineup.

It’s still the strangest college basketball game I ever saw.

Arkansas won it, 39-38. Texas did get its first-ever at-large NCAA bid. But the Horns seemed worn out, mentally and physically, and fell to Oklahoma in the opening round the next week.

After advancing through several opponents, Sutton’s Hogs, aiming for a second straight Final Four appearance, were felled by a grove of Sycamores, one sturdy tree in particular, in the regional final. Larry Bird, averaging 29 points and 15 boards, led Indiana State past Arkansas en route to an eventual loss in the national championship game to Michigan State and its own star, Earvin Johnson.

So, a postscript to the Abe versus Eddie bout, more than four long decades later.

Abe Lemons died in 2002 and was buried in his native Oklahoma, two months before he would have turned 80. He had walked away from hoops a dozen years earlier.

Until this spring’s election, Sutton lived on as the only men’s college coach with 800 wins to not have been knighted by the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass.

Three years after the “I’ll tear his Sunday clothes” promise, Abe Lemons was dismissed as head coach by the Longhorns’ new athletic director, DeLoss Dodds. Lemons had brought Texas to national basketball prominence for the first time since the years immediately after World War II, but it wasn’t enough to hold down the UT power brokers who didn’t like Abe’s sass and one-liners or a perceived lack of interest in his players’ academic prowess.

He finished 5-10 against Sutton’s Hogs. Seven of UT’s losses had been by fewer than seven points.

“He should have won,” Lemons said of Sutton’s record against him. “He had better players.”

Lemons rebounded by heading back to Oklahoma City University where he had first established his reputation for building strong basketball teams. He retired in 1990 with 499 career wins and speculated that perhaps it was best that he went out just shy of a benchmark.

“People seem to like you better when you finish just short.”

Sutton took the Razorbacks to the NCAA tourney nine times in 11 seasons at Arkansas. He was rewarded in 1985 with one of the plum positions in his sport, hired as head coach at the University of Kentucky.

But the dream job turned nightmarish in just a few years.

NCAA officials said they had evidence of numerous violations so egregious that they were considering the death penalty for the Wildcats’ storied program. Sutton resigned, beating the buzzer on what seemed an all but certain termination.

Kentucky was nailed with three years of probation and a two-year ban from postseason play.

Permed hairdo still intact, Sutton sat out 18 months and moved to Stillwater, just down the lane from Abe. There, he quickly resuscitated his career and revved up Oklahoma State basketball for 16 seasons.

Thirteen times he landed OSU in the NCAA playoffs. All that, even amid an apparent battle with the bottle. The coach was sidelined by a DUI and car accident and acknowledged previous treatment at the Betty Ford Clinic.

He eventually resigned in 2006, just two wins under the magic mark of 800 career triumphs. Sean Sutton, his son, replaced him as the Cowboys’ trail boss.

But Sutton was driven by the prospect of eternal company amid the all-time greats atop basketball’s Mount Olympus. In December 2007, he took a coaching job at the University of San Francisco to ensure an 800th win.

Sutton went 6-13 in an abbreviated stay but got his landmark victory.

He retired with a stellar 804-328 record and an impressive .710 winning percentage.

All the credentials were there, but the Hall of Fame voters wouldn’t wave Sutton in, despite six appearances on the ballot. His name didn’t even make the ballot in 2016 and 2017.

Some hoops experts felt Sutton’s absence from the Hall was unfair but basketball’s closest observers strongly believed Sutton’s admission had been halted by the taint of whatever went on in Lexington. Still, a number of Sutton backers pointed out that two others with dark spots on their moral record in Bluegrass Country — Adolph Rupp and Rick Pitino — were already on pedestals in the Hall while Eddie was still scratching at the door.

Was Abe Lemons still haunting and taunting Eddie from the grave?

Finally, the seventh ballot turned lucky for the venerable Sutton on April 3. But now he’s already gone and will be posthumously inducted into the Hall of Fame, as will Kobe Bryant. The stellar 2020 class includes Tim Duncan, Kevin Garnett and Rudy Tomjanovich.

Perhaps, in closing, we should consider one more Abe Lemons observation regarding his nemesis.

An Oklahoma writer, way back in the ’90s, asked the retired coach about Sutton, at OSU, attempting to get his big 500th win. It would enable Eddie to pass up his old rival, Abe, who had shrugged off the hoopla and settled for 499.

How would it go down?

The response was a pure dash of bitter Lemons.

“He’ll probably win on a bad call,” Abe said. “That’d be my guess.”

Write to Larry Carlson at lc13@txstate.edu