Bugle and the Flag by Bill Little

BILL LITTLE COMMENTARY: THE BUGLE AND THE FLAG PETE EDMOND

May 28, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

When America was drawn into the conflict in Europe, Pete Edmond gave up his banking job to enter Officer’s Training Camp, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He left for France in April of 1918.

At first, he wrote letters every day – even if they only contained a few lines. A last letter arrived on October 24, 1918. It painted a grim picture of the war on the western front as the fate of the world hung in the balance. That was the last his family ever heard from Pete Edmond. Months later, after searching for word through the military and the Red Cross, the family received a cablegram from General Pershing himself.

On August 6, 1918, he made a personal reconnaissance of German positions in the area, covering almost two miles of ground under heavy fire. For that, he was awarded the Silver Star, the third-highest recognition in the US military.

On September 26, he was wounded, but refused to go to the rear and stayed with his men as company commander.

And then, on October 11, 1918, he was killed charging a German machine-gun position in the battle of the Argonne Forest, one of the bloodiest campaigns in the history of American warfare, where 26,000 American soldiers died.

He died fighting for his men and fighting for his country.

PETE EDMOND WWI

05.26.2014 | Bill Little Commentary

Bill Little commentary: The memorial in the stadium

By Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

The stadium was built as a memorial to all those Texans who were killed in World War I,

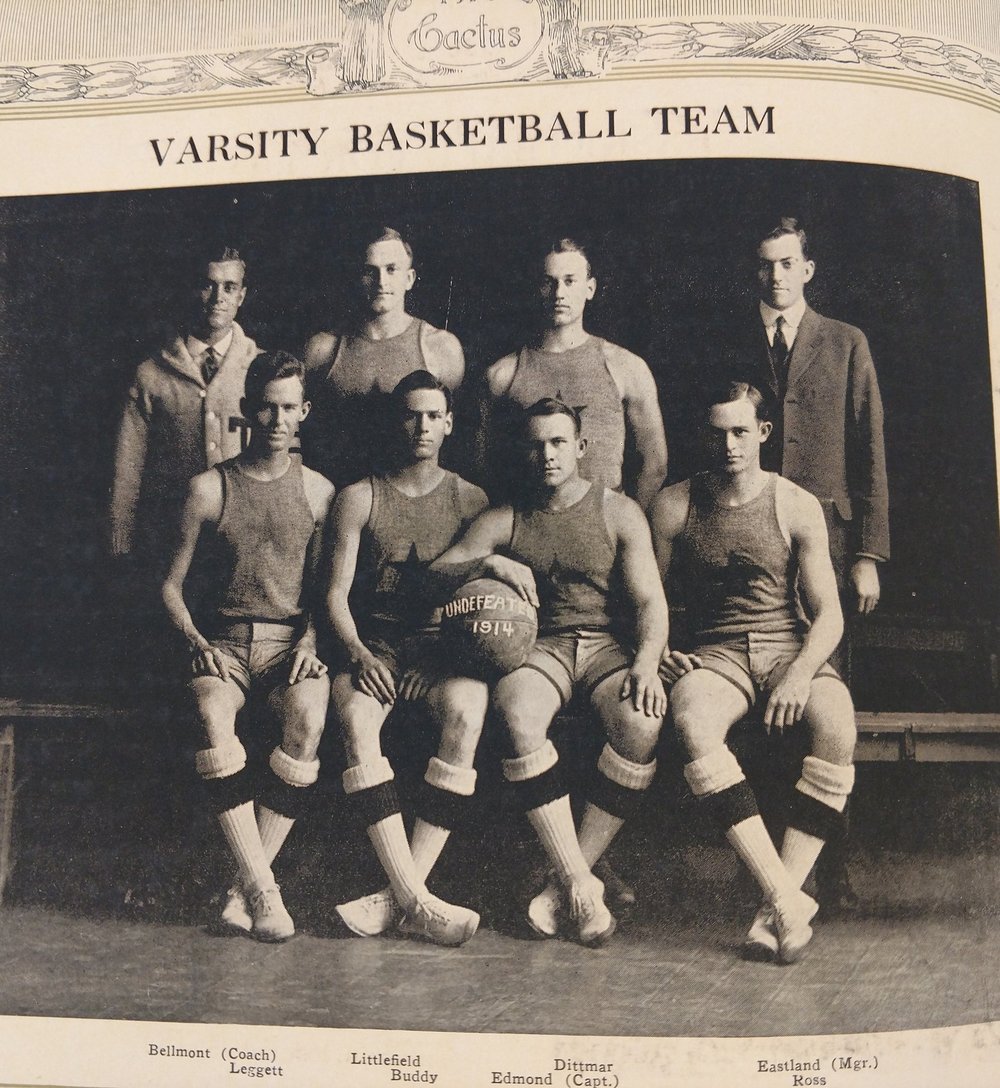

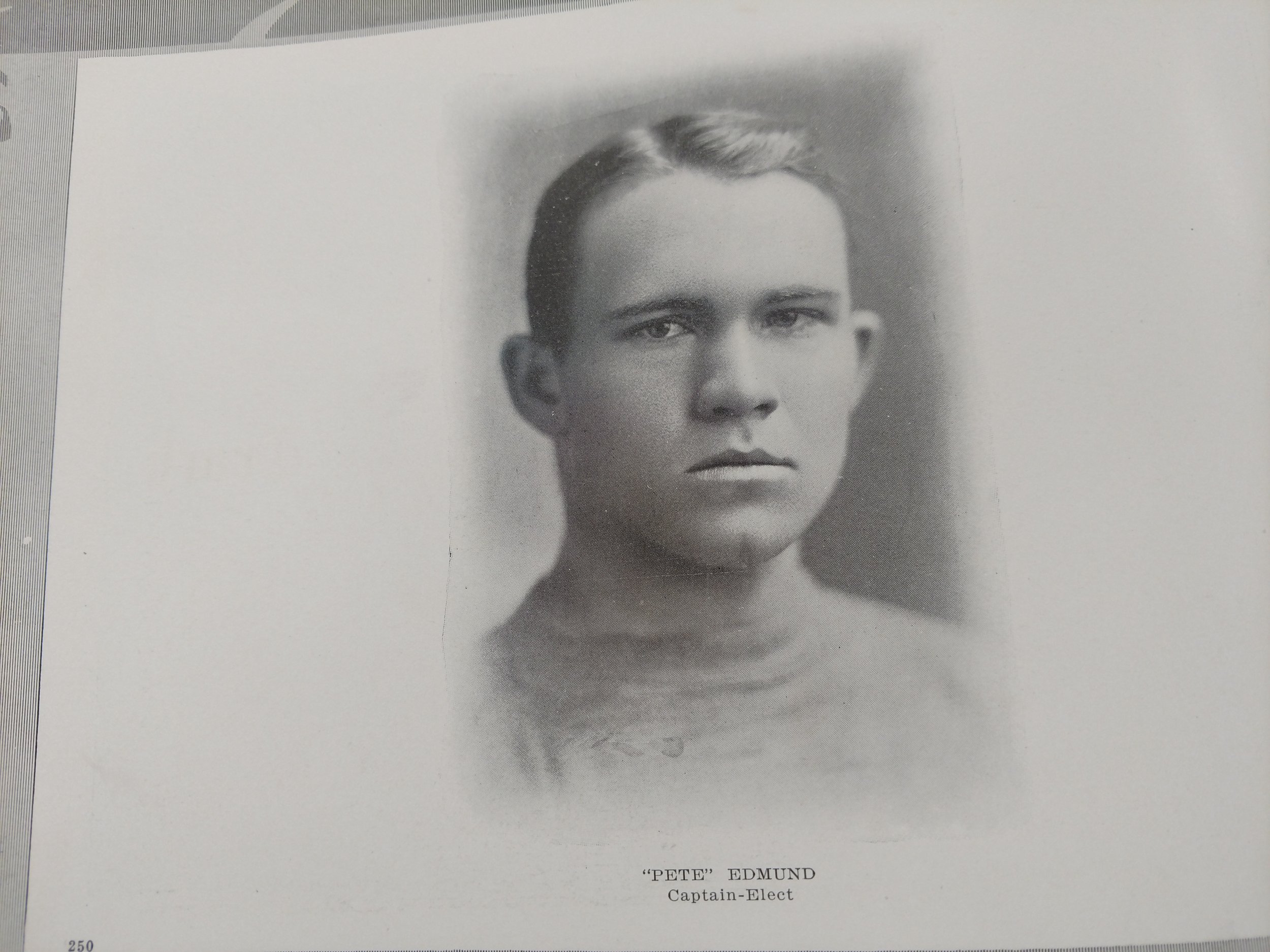

Probably the best of the former players was a multi-sport star named Pete Edmond.

The first thing I noticed in the Hall of Honor file of James A. “Pete” Edmond was a letter envelope dated Sept. 1918. It had three one-cent stamps on it and was addressed to Lieutenant James Edmond, Company G., 39th Infantry, Fourth Division, American Expeditionary Forces, France.

It had been marked “Return to Sender.”

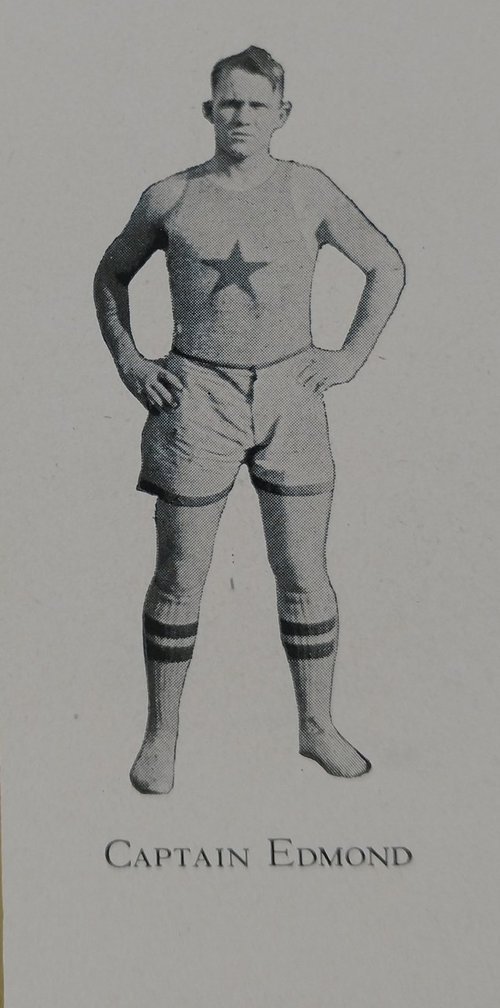

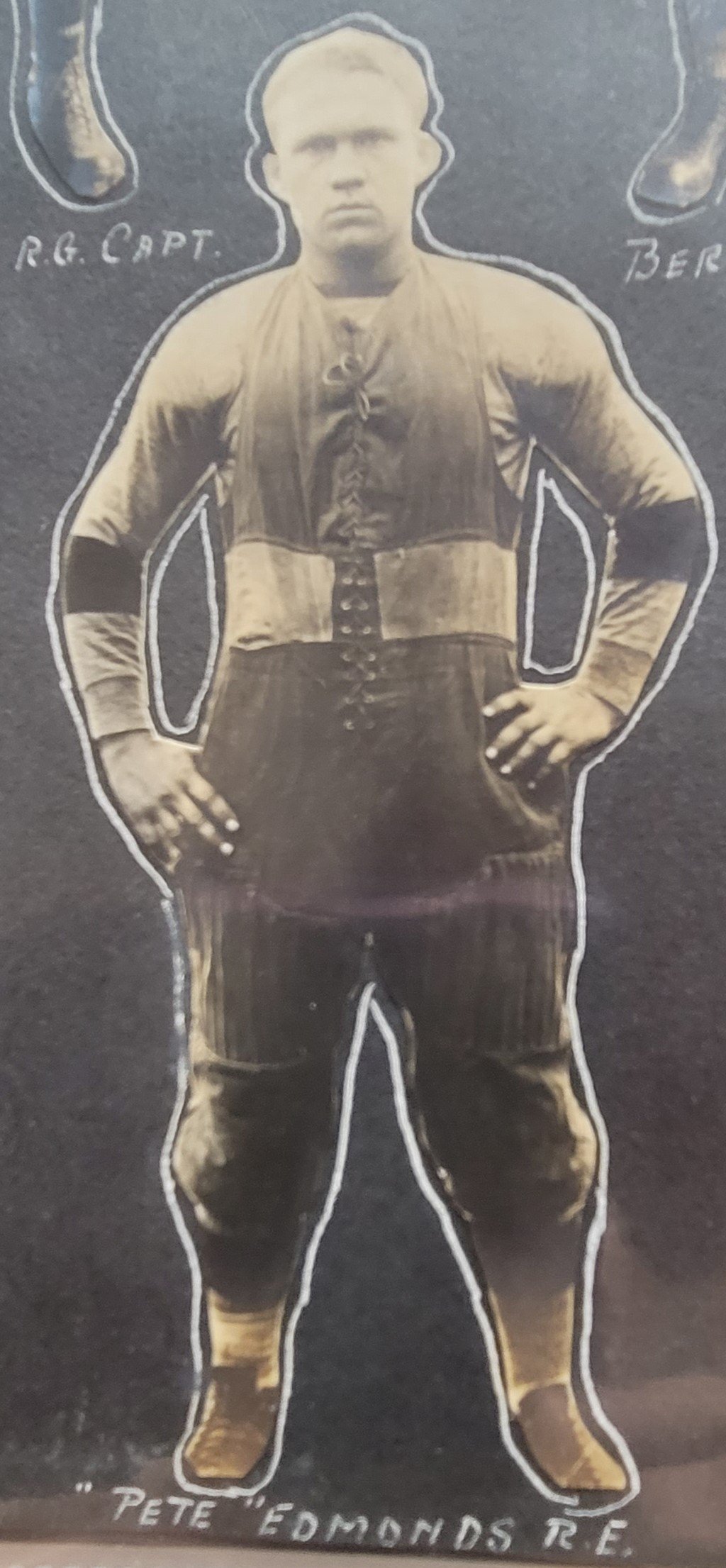

Pete Edmond was one of the greatest student-athletes in the early days of The University of Texas. From the football season of 1913 through the baseball season of 1916, he earned eleven letters: three in football and four each in basketball and baseball. He also competed in wrestling, even though it was not an official UT sport. In the classroom, he held a student assistantship in history. He was a member of the Phi Delta Theta fraternity, the Friars, and the Arrowhead.

Edmond was outstanding as a player in all sports. As an end in football, he was matched in 1913 against Notre Dame’s Knute Rockne, who would go on to become one of the most famous coaches in the history of the college game. Years after the Irish beat the Longhorns, 30-7 that season, Rockne recalled Edmond:

“I’ll never forget that player as long as I live. I played football against the best teams in the east. I played against the best in the west and against the best of other sections, but never was I forced to go up against a better wing. He was as clean as a whistle, but he played hard football…oh, how hard he did play, and I have always admired him for it.

“That was one great star in the southwest who did not get his just dues when all-American teams were picked. I can certainly vouch for that fact. He was a terror when his team was completely overwhelmed. I have often wondered what heights he achieved when playing against a traditional rival?”

In the years following his graduation from Texas, the Waco native married and found a job in the banking business in Orange, Texas. As The United States involvement in World War I deepened, Edmonds entered the U.S. Army and received a commission as a second lieutenant.

But you cannot capture on a plaque the story of Pete Edmond or the message his life sent about the combined values of patriotism, and the challenges of real war, and the philosophies of sport.

That, instead, is tucked away in that old file, where ghosts of the past march as a solemn reminder of why, on Memorial Day, we should celebrate all of these men and women and what they have done.

Pete Edmond gave up his banking job to enter Officer’s Training Camp and was commissioned as a second lieutenant assigned to the Fourth Division, 39th Infantry. He sailed for France in April 1918.

His family knew he was in Paris as America celebrated Independence Day on July 4, 1918. In the days before instant communications with cell phones and the Internet, the written word was all that a soldier and his family had.

“Only little letters of a few lines came to us,” wrote a member of his family later. “But every day, he wrote those few lines. A last letter and a rough picture came Oct. 24.”

Months later, after searching for word through the military and the Red Cross, the family received a cablegram from General Pershing himself.

“Deeply regret to inform you….” it began. It went on to describe where Edmond had been buried, in what would become the largest overseas cemetery in United States history.

Later, the family would begin to piece together the story of lieutenant Pete Edmond.

In a field “near Ferne de Filles, St. Thibaut, France,” on Aug. 6, 1918, he made a personal reconnaissance of German positions in the area, covering almost two miles of ground under heavy fire. For that, he was awarded the Silver Star, the third-highest recognition in the US military.

On Sept. 26, at Nantilles, Edmond was wounded but refused to go to the rear and stayed with his men as a company commander.

Leaders do that; we’re told.

And then, on Oct. 11, 1918, he was killed charging a German machine-gun position in the battle of the Argonne Forest, one of the bloodiest campaigns in the history of American warfare.

He died fighting for his men and fighting for his country.

One month later, on Nov. 11, the “War to End Wars” was over.

It has been almost one hundred years since Pete Edmond sailed for France, and in a sense, he is still there. His address there would be plot C, Row 37, Grave 14 in the American cemetery where the dead of the battle of the Meuse-Argonne are buried at Romagne, France.