Louis Jordan by Jim Carr

LOUIS JORDAN

— Jim Nicar (@JimNicar) September 10, 2018

By 1957, the Texas Longhorn football program had 64 years of history and had produced four consensus All-Americans and seven players who would later be enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame. But when the Texas Athletics Hall of Honor was created that year and inducted its inaugural class of four, the only athlete in that group was the late Louis Jordan. That’s how highly esteemed he was in the history of UT athletics over 40 years after he had graduated.

Louis Jordan was in the first class inducted into the Hall of Honor in 1957. Jordan lettered three years in track and 4 in football. Ironically, a proud German, Louis, would die from shrapnel from a German artillery shell fighting for America.

05.26.2014 | Bill Little Commentary

Bill Little commentary: The memorial in the stadium

·

By Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

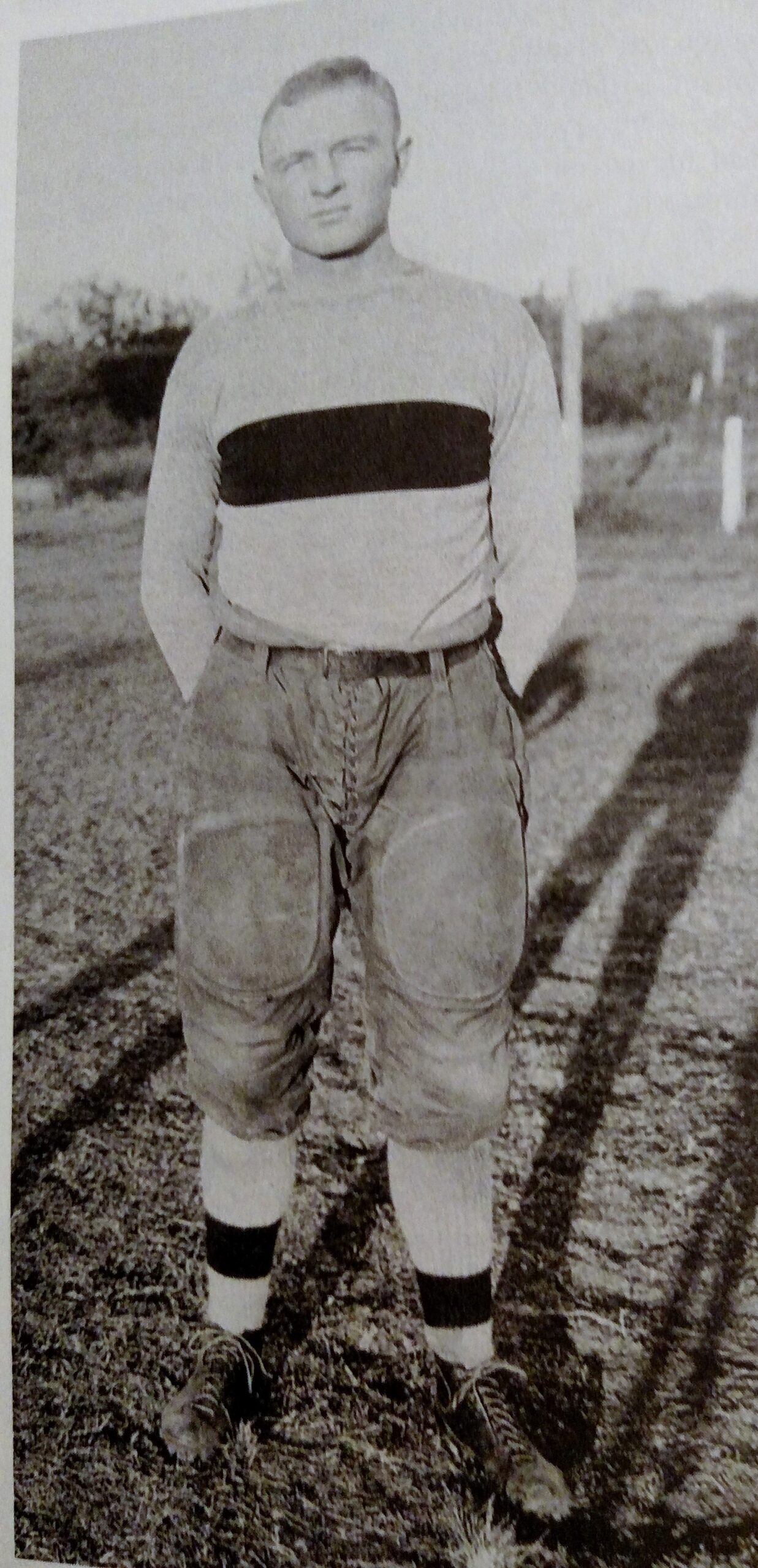

One of the most popular students at The University of Texas from 1911-1915 was a young man of German heritage from Fredericksburg, Texas, named L. J. “Louis” Jordan.

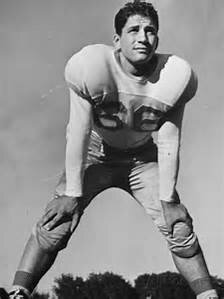

Jordan was like everybody’s big brother. He was a round-faced blond who stood over six feet tall and weighed 205 pounds, which was significant for the time. He was exactly what you would want in a player by timeless standards.

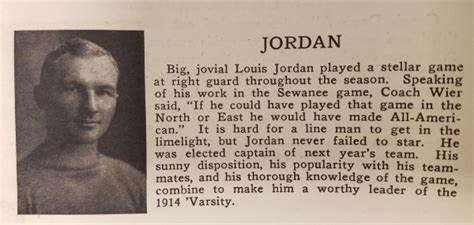

Jordan was so gentle by nature that he had to be coaxed to play football. But he became his era’s greatest lineman, offensively and defensively, when he did. He became the first Texas player to earn national recognition, earning Walter Camp second-team all-American honors in 1914. Significantly, this was when people in the East barely recognized that football was played west of the Mississippi.

Jordan made the electrical engineering honor roll every year, and he helped Texas teams post a 27-4 record during his four years, including a perfect 8-0 mark as a captain of the team in his senior season of 1914. While the Longhorns played most of their games in Austin, Dallas matters in this story. In Dallas, before a crowd of 7,500 at Gaston Field—the Texas league baseball park—Texas and Oklahoma met in what was then a showdown for power in the Southwest.

It is also notable that the game was usually played at the State fairgrounds, but horse racing had taken over the fair that day.

Oklahoma’s Hap Johnson ran the opening kickoff back 85 yards for a touchdown, and the Sooner hopes soared. In those days, opposing fans openly bet with each other, and a lot of Oklahoma money went up then. While the bets were coming, Louis Jordan gathered the Texas team around him for the ensuing kickoff.

Clyde Littlefield, one of the great Texas legends playing on the team, remembered the speech until he died.

“He told us in no mincing words, with a few cuss words in German and some in English, ‘Nobody leaves this field until we beat the hell out of them.'”

Let the record show that Texas scored 32 straight points, winning 32-7. Eleven men started the game, and the same eleven finished it, and an awful lot of Oklahoma betting money stayed in Texas.

Jordan lettered three years in track and four in football at Texas, and his athletic skill was superior to those of players of his time. But what he brought to the game is the enduring quality that every coach searches for in every player they seek and every company worth toot desires: leadership.

They inducted Louis Jordan in the first class of the Longhorn Hall of Honor 42 years ago. He was one of only four men inducted and was the only former athlete chosen.

Sadly, he was not there to get the award.

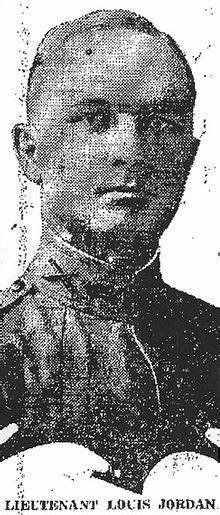

As the years go by, fewer and fewer of us remember World War II, and almost none remember World War I. Only the history books and the Internet will tell us of the Luneville Sector in France, where brave young men like Louis Jordan went to fight for that elusive dream called freedom and peace. Luneville was France’s “quiet sector,” where the French troops helped harden the young Americans for the battle with Germany. Ironically, a young man who was so proud of his German heritage would go there and die.

On March 5, 1918, Louis Jordan died in another land at another time. Legend has it that two days later, on March 7, 1918, German artillery shells suddenly turned on the “quiet sector,” one shell hit a bunker where 21 Americans were hunkered down. The dirt collapsed on the soldiers, trapping them alive.

In the confusion that followed, they say a prominent blond-headed American who nobody had seen in that unit from New York was cussing, yelling, urging the rest of the unit to dig with their bare hands to try to save the soldiers. They say, too, that he was seen charging at the artillery position, fighting with such rage that even hardened soldiers retreated.

Many soldiers died in that bunker, but those who lived praised their comrades of the 69th for risking their lives to save them. No one will ever know why the artillery shelling stopped.

News of the death of Louis Jordan, the first Texas officer killed in action, saddened the entire UT community. When they dedicated the new stadium in 1924 as Texas Memorial Stadium—in honor of the war veterans—the people of Fredericksburg erected a flagpole at the south end of the stadium where the Steinmark scoreboard stands today. It stood until 1971. Fred Steinmark, a Texas safety on the 1969 National Championship team, battled cancer until he died in 1971. Texas players on the way to the field touch his picture to symbolize the courage he showed. That spot is hallowed ground when it comes to courage.

Louis Jordan is important to us today because he represents what this football game means to both sides. It is a challenge of the human spirit and a contest played only on a Saturday in mock war. Louis Jordan reminds us that leadership and drive matter not only in a football game but in life.

And somewhere in France, his ghost may be walking even in the following millennium, telling them all that “nobody leaves this field until we beat the hell out of them.”

When the Veterans Plaza was completed, the new Jordan Flag Pole was relocated beside the soldier’s statue.

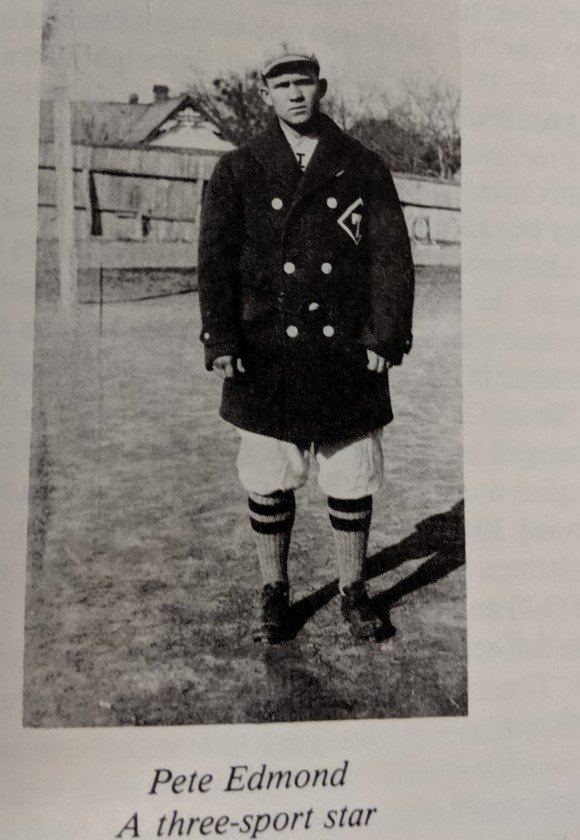

Until Jordan’s remains were moved to Fredericksburg, there were three wooden crosses in the fields of France in 1918—each for a former Longhorn football player who died fighting in World War I. Jordan and Edmond are in the Longhorn Hall of Honor and rank among the best athletes in school history. The legacy of the Third has endured uniquely for almost 100 years.

The people of Fredericksburg erected a flagpole to honor their favorite son, Louis Jordan. General Pershing sent a personal message to the family of Pete Edmond, who won a Silver Star. Mrs. John D. Kane of Fort Worth, Texas, gave a scholarship to honor the memory of her son.