Abe Lemons by Larry Carlson

Remembering Lemons, Texas’ NIT title-winning team

On the eve of the NCAA crowning a national champion at the Final Four, guest columnist Larry Carlson remembers the NIT-winning Texas squad of Abe Lemons 40 years later. Article written for 247 Sports

LARRY CARLSON Apr 1st, 2018, 8:00 AM35

Long before Longhorn basketball backers swooned for Tom Penders’ ” BMW Ultimate Scoring Machine” of Blanks, Mays, and Wright, before Rick Barnes and KD, a coach with a sharp tongue and a star player with a soft middle, put their stamp on hoops at Texas.

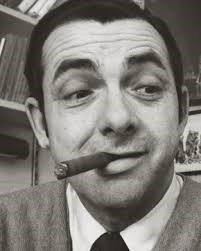

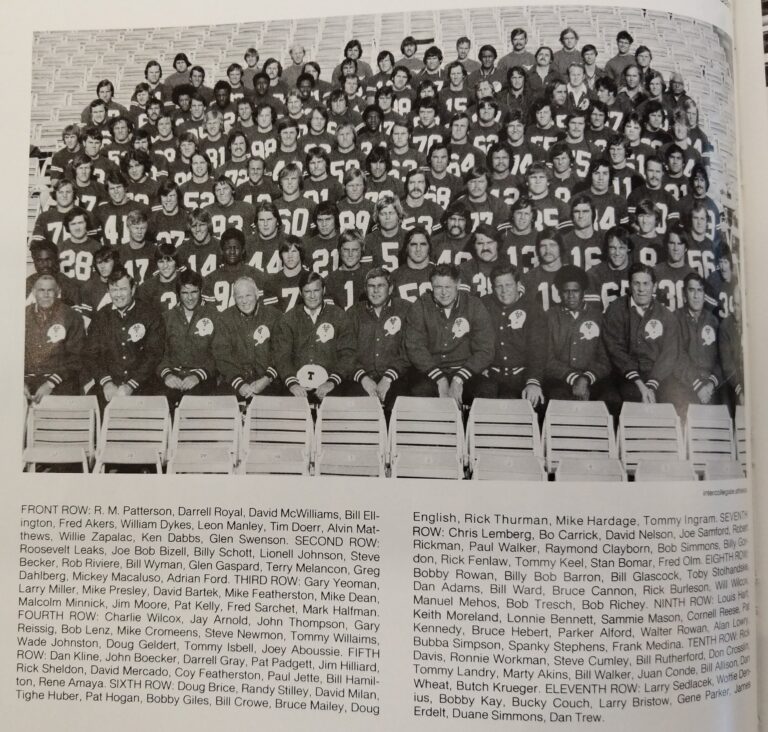

When legendary basketball coach Abe Lemons inherited a moribund Texas program coming off its third straight losing campaign in 1976 and improved the previous year’s 9-17 record into a 13-13 mark, his five-season, $30,000 annual salary negotiated by athletic director Darrell Royal already looked like a pretty fair country bargain. Expectations were not exceptionally high based on the talent at hand. Abe, a wise-cracking, stogie-chomping Oklahoman who could match his boss in quotable quotes, had been asked early on at The Forty Acres if his team should be ranked in the top 20.

He answered with his own question.

“In the state?”

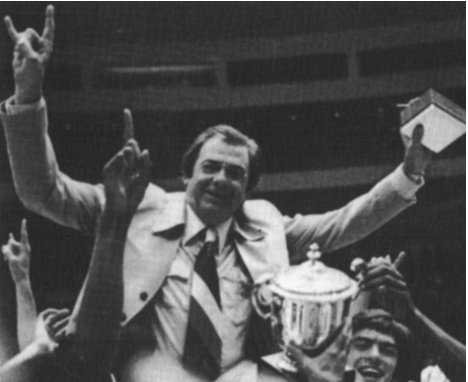

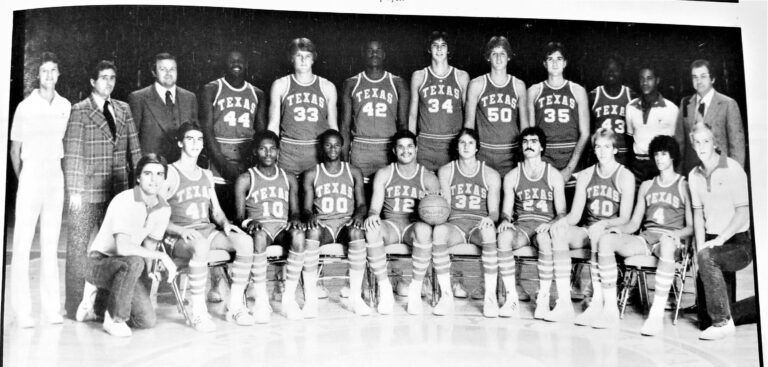

Lemons turned a nondescript crew without a big man into co-champions of the Southwest Conference and kings of the National Invitation Tournament in New York.

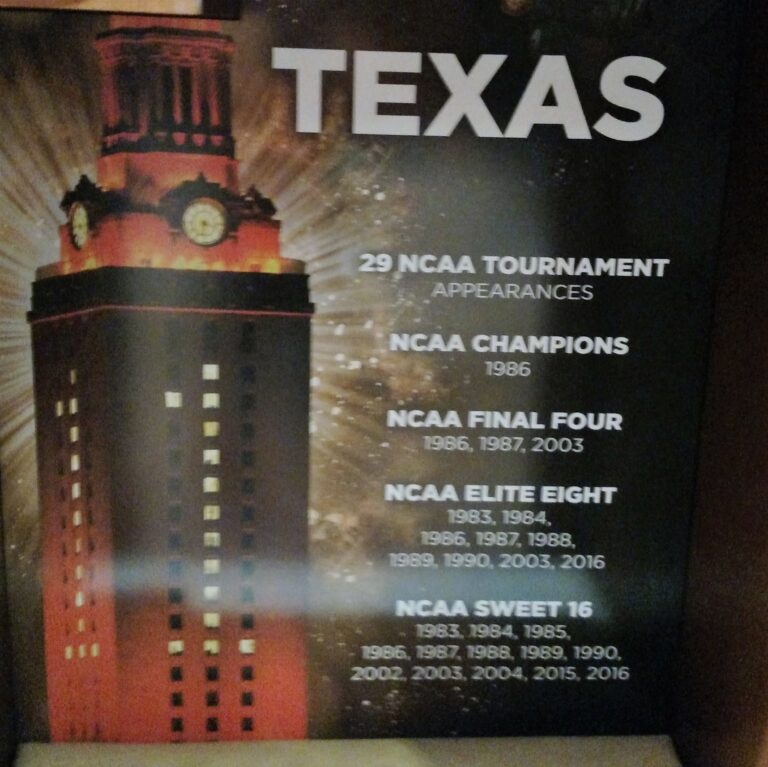

That was back when the 32-team NCAA field left out numerous fine teams, and the NIT was a real prize rather than a consolation junket or participation ribbon. The Cinderella Longhorns went 26-5, and Lemons wore laurels as National Coach of the Year, the first UT hoops coach — and only thus far — to be so honored.

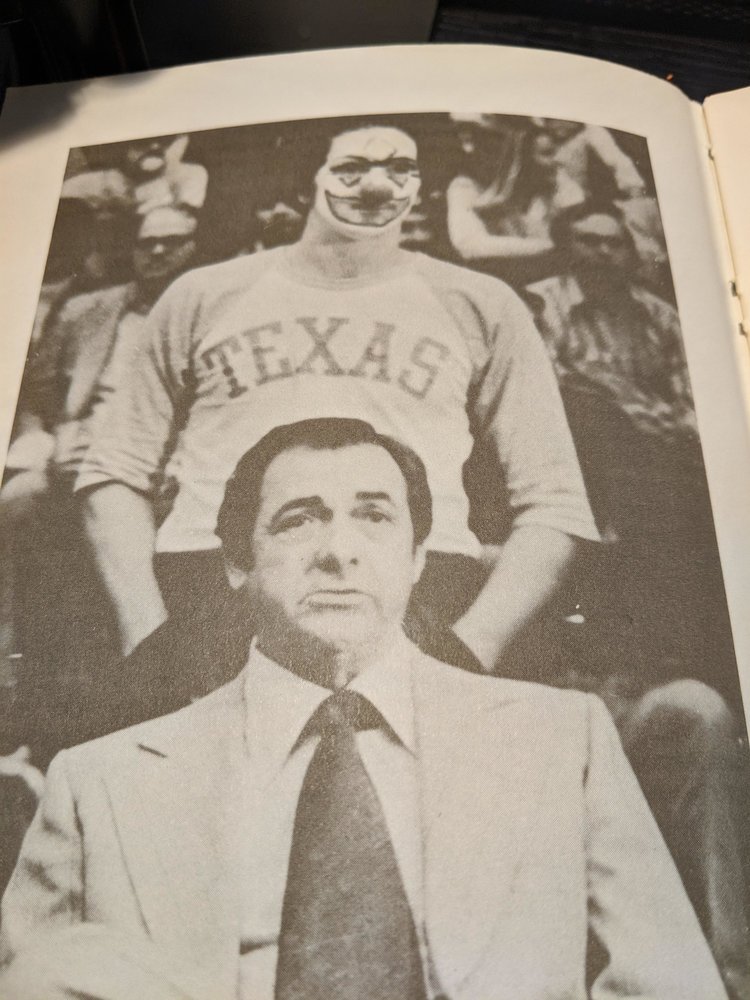

Now the inaugural roundball season at the spanking new Special Events Center, soon to be nicknamed the Super Drum, soon to be re-named the Frank Erwin Center, came in with a crushing of hated OU. Whereas old Gregory Gym frequently failed to fill its modest capacity, the Drum was built for more than doubling the fan attendance and was soon packing in close to all its 16,000 seats at the spacious new home.

Lemons, frequently pairing cowboy boots with leisure suits, was beating the hell out of bigger, faster teams that looked better in their uniforms than did Texas. The characters might well have been straight from a “Hoosiers”-type underdog script, ten years early.

Gary Goodner was the scowling, scrapping, undersized 6-7 “center,” a veteran of three non-winning seasons in burnt orange. He didn’t say much and didn’t score much but he got his job done.

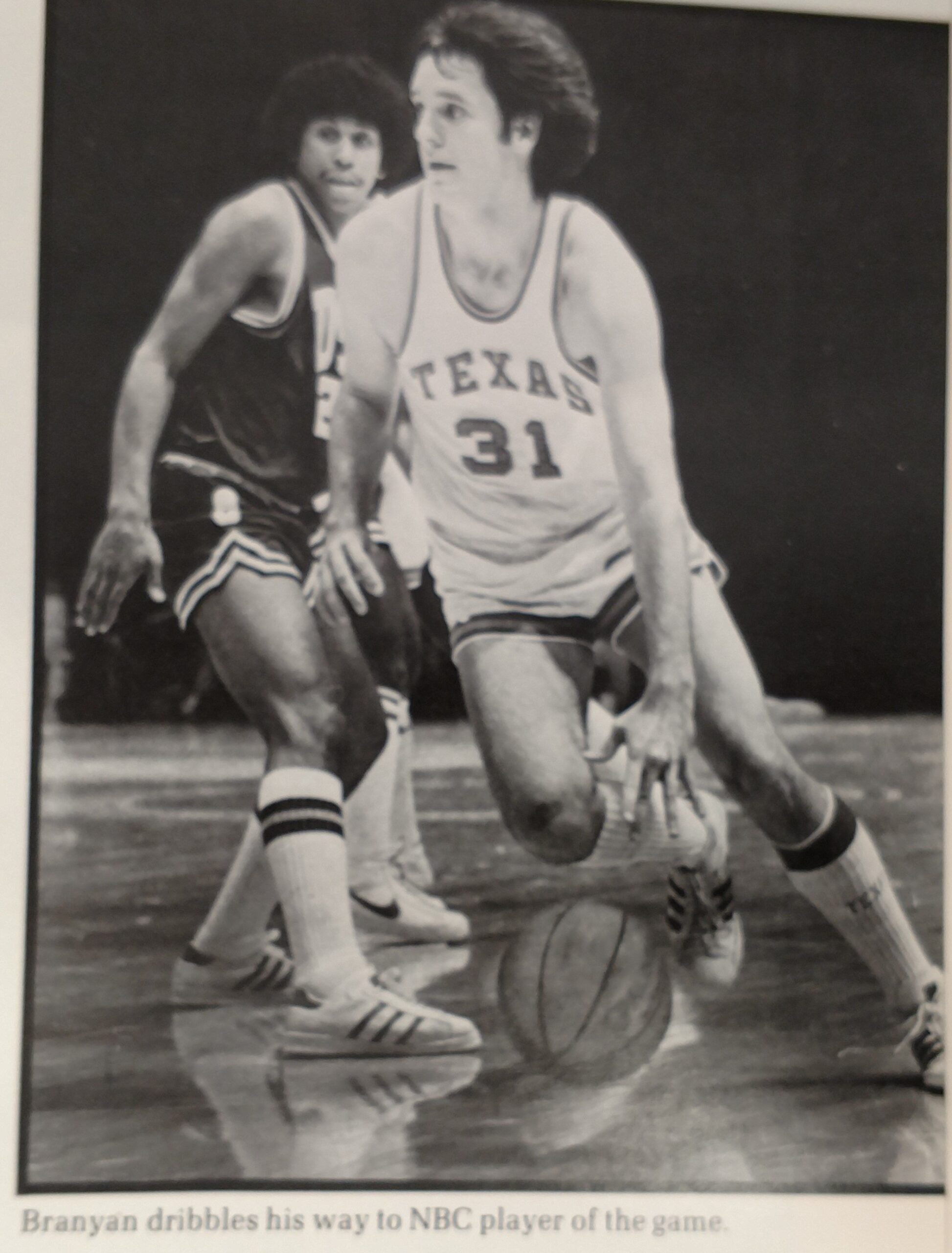

Tyrone Branyan, also 6-7, was a forward who could rarely dunk in practice, an early poster-child for “White Men Can’t Jump.” But he was the classic savvy “lunch pail” guy who was always in position, always somehow got the clutch bucket or rebound, always frustrated his man. “Tyrone is the last of a breed, rare as the white buffalo,” Lemons once opined, not referring to Branyan’s pasty complexion, just marveling about another solid showing by his vertically challenged gamer who could do nothing except win.

A slightly flashier trio was often responsible for most of the points on the scoreboard.

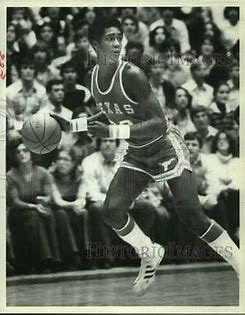

Johnny Moore was the playmaking point guard from Pennsylvania, slick, quick and destined to have his jersey retired by the San Antonio Spurs.

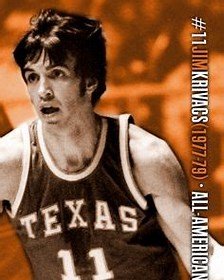

Jim Krivacs was the scrawny 6-1 Indiana boy, by transfer from Auburn, who must have practiced by launching peanuts into a Coke bottle as a kid. Krivacs was the first UT player I ever heard described as a gym rat and If three-pointers had been in the rule book when he played at Texas, he would likely own the scoring records even today. Krivacs was popping shots in from the Capitol building, making nets hiss and fans roar. It was hard for opponents to block shots launched from 30 feet away.

The small forward was Ron Baxter of L.A., a rare well-regarded Texas signee, now with a solid freshman year under his growing belt. He would go on to All-SWC honors for three stellar years and finish his UT career as the all-time leader in scoring and rebounding. But the 6-4 Baxter was a frequent target of enemy fans who taunted him with pizza boxes and calorie-packed insults. You see, this easygoing Californian sported an ample paunch that many dared call “a gut.” It never stopped him from running the floor, out-jumping bigger foes, slamming home dunks or feeding his teammates, and the taunts never registered. But some of us in the reportorial pool decided to ask Abe about Baxter one day after practice. The question was, how could a guy run that much every day, drill that hard and still have a stomach that made him look like an honorary sports reporter or soft, lazy armchair fan?

“Well,” Abe sniffed. “Y’all ever seen him at the table?”

We all testified that we hadn’t.

Lemons snickered, then followed through with the payoff.

“The sumbitch eats like he’s got seven a— h—-s.”

It was vintage Abe.

John Danks

Many of the best soundbites and quotes he delivered were doomed for the cutting room floor, too profane for TV, radio and newspapers of the day. He would hold court after games, lighting up a cigar and expounding on just about anything, including the game just concluded. He entertained the media and made many of us lazy because he didn’t require questions; he was on a stream of consciousness that frequently brought guffaws and belly laughs. He didn’t shy from occasional compliments of his players but he didn’t deem many of them worthy of court time. Besides freshman forward John Danks — the future father of baseball stars John and Jordan — of Beaver Dam, Kentucky and a few others, Lemons essentially had no backups.

“I never substitute just to substitute. I play my regulars. The only way a guy gets off the floor is if he dies,” Lemons said, explaining his limited rotation.

He certainly wasn’t afraid to criticize players, something rare in today’s era of sensitivity training and pronouncements of love for “team families.” Perhaps Lemons’ most famous line was one he said he told a player who had scored but a single point by halftime.

“You scored one more point than a dead man,” Lemons proclaimed, giving birth to the title of a book of Abe’s quotes that was subtitled “the irresistible, sardonic humor of Abe Lemons” edited by the late Longhorn-friendly writer, Robert Heard.

Another Lemons gem was later singled out as the sports quote of the 20th century by USA Today. “Doctors bury their mistakes; ours are still on scholarship,” he snarked.

There weren’t many serious mistakes on the playing or coaching end during the ’77-’78 season. It was one that no modern-era Texas fan had dared to dream of. Even in the rare defeats, Lemons’ crew was earning praise, losing by a point on the road to USC and hanging tough with defending national champ, Marquette.

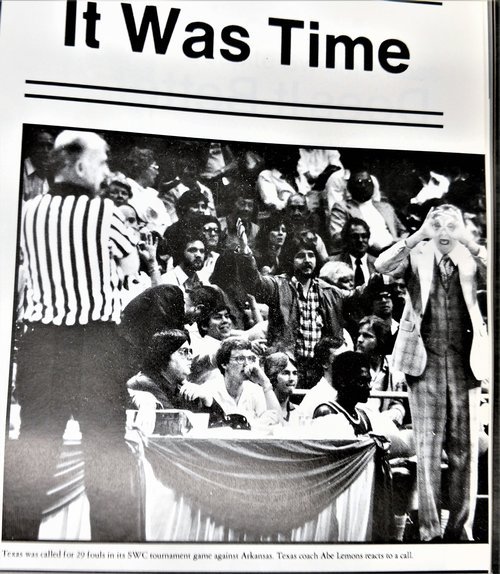

There was an eight-game win string, then a later one that stretched to nine victories. The Horns beat third-ranked Arkansas in Austin and shared the conference title with the Hogs, finishing the regular season at 22-4 (14-2 in SWC play), ranked 12th in the country, a rating undoubtedly lowered by a quarter-century of Texas being considered “only a football school” in the eyes of national voters.

The Steers might have done some damage in the NCAA tournament but fell by two points to Houston for the automatic bid as the SWC rep. Arkansas got in with an at-large bid and made it to the Final Four behind its three basketeers, the remarkable headliners Sidney Moncrief, Marvin Delph and Ron Brewer.

Texas refused to pout about exclusion from the NCAA’s and roughed up Temple, Nebraska and Rutgers by comfortable margins to reach the NIT final against pedigreed North Carolina State. Lemons was wowing the Gotham City writers with his country witticisms and jabs about a variety of topics. He complained about the cost of a Manhattan breakfast by musing that the chickens laying those kind of eggs must have a cushy life, pampered under little parasols. The Madison Square Garden writers and fans couldn’t get enough of this graying Southwesterner who was alternately charming and sarcastic but almost always honest and humorous.

Nobody in Wolfpack garb or waving ACC banners was laughing at the results of the championship game as Texas cruised to a comfortable 101-93 triumph. Moore scored 22 points and the tourney’s co-MVP’s, Krivacs and Baxter, lit up the Garden with 33 and 26 points, respectively.

Lemons truly was the toast of the town and returned to Austin on the biggest basketball high UT had known since the Final Four appearance in 1947. The new, catchy Queen song that had rocked the Super Drum all season long now seemed truly apropos, as Longhorn fans thundered “We Are The Champions,” and the record proved it.

Abe Lemons’ next Texas teams were entertaining contenders and earned national attention never before bestowed upon UT hoops.

But Lemons would be gone after only six seasons in Austin.

Now skying in the rarefied air of a $52k contract, he was fired by a first-year Director of Athletics named DeLoss Dodds who was getting an earful from some fat-cat boosters and administrators who thought Lemons was too lax about academics, never issued a curfew (he had once said he didn’t believe in curfews because it was always the best player who got caught), was too opinionated and lacked a sense for what is now called political correctness.

The unlikely end came in March of 1982, less than two months after Texas had burned rubber in a flashy 14-0 start, rising to fifth in the nation, then its highest regular-season ranking ever. But the wheels came off when sophomore Mike Wacker, the early season national leader in rebounding, suffered a devastating knee injury in what would turn into UT’s first loss. The Horns would win just two of their final 13 en route to a 16-11 finish.

Still, Lemons’ dismissal more than a week after the season’s end came as a shock to players, fans and the coach himself. But he uttered a few more classics to the reporters who saw him off. Lemons said he wanted to purchase a glass-bottomed vehicle so he could see the look on Dodds’ face when he ran him over.

Then Abe’s buzzer-beater shot at the suits was this: “I hope they notice the mistletoe tied to my coattails as I leave town.”

Larry Carlson saw his first Longhorn victories in 1960 and grew up in a bedroom that was painted burnt orange. He was the sports director and host of “Longhorn Locker Room” for KVET radio from 1977-79 and later co-hosted “Longhorn Pipeline” on San Antonio’s ESPN Radio affiliate from 2008-2011. He has been teaching broadcast journalism at Texas State University since 1984 and resides with his wife in the Alamo City.