The Ballyard and the Graveyard.

THE BALLYARD AND THE GRAVEYARD

by Larry Carlson ( lc13@txstate.edu )

It had been a long time since I had been to “The Disch” for a Longhorn baseball game. An embarrassingly long time, really. Dog years.

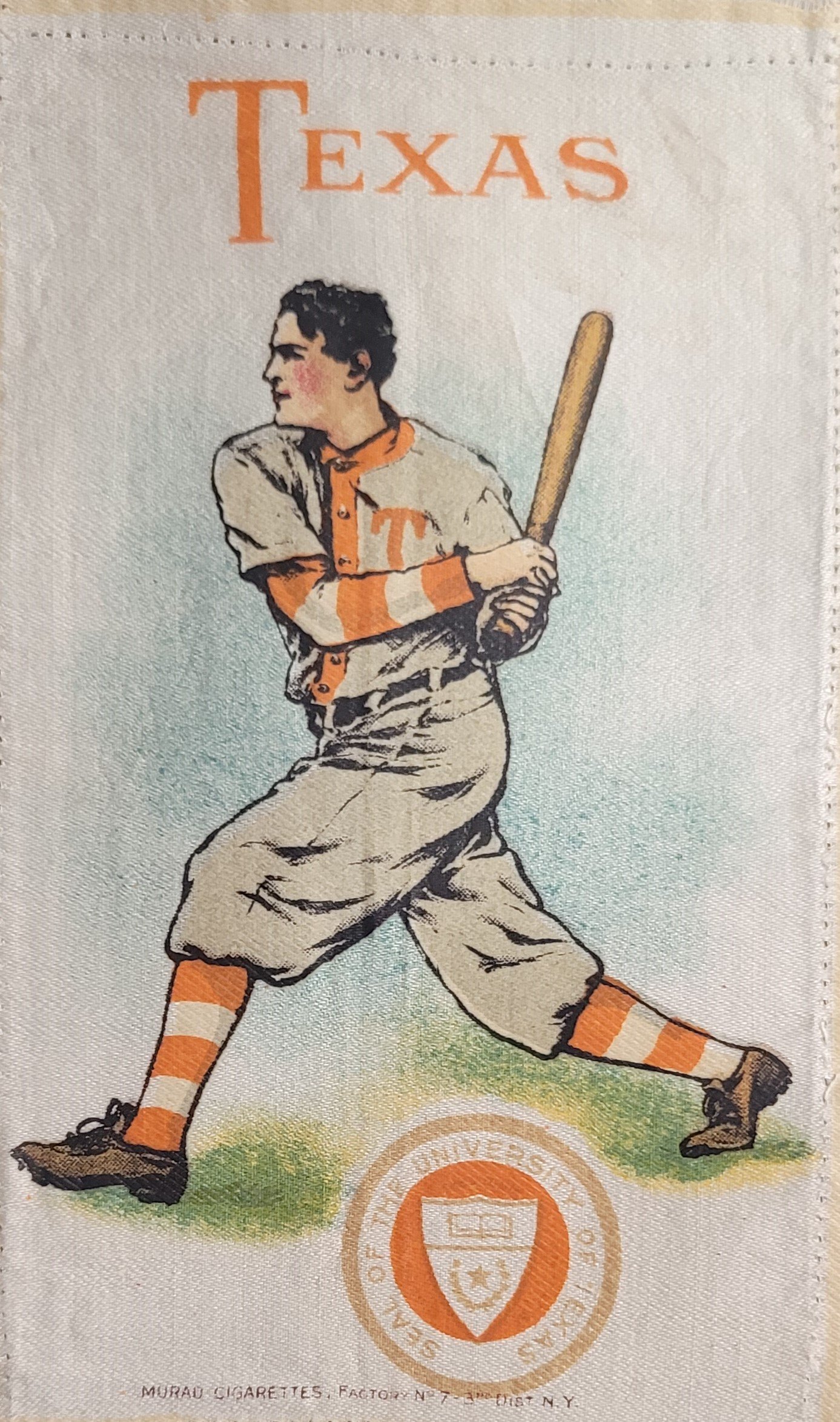

I mean, I’ve been keeping up with the hardball Horns since I was a teenager and they still performed at cozy Clark Field, replete with Billy Goat Hill spanning much of the outfield. Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth had played there against UT in a Longhorns-Yanks exhibition.

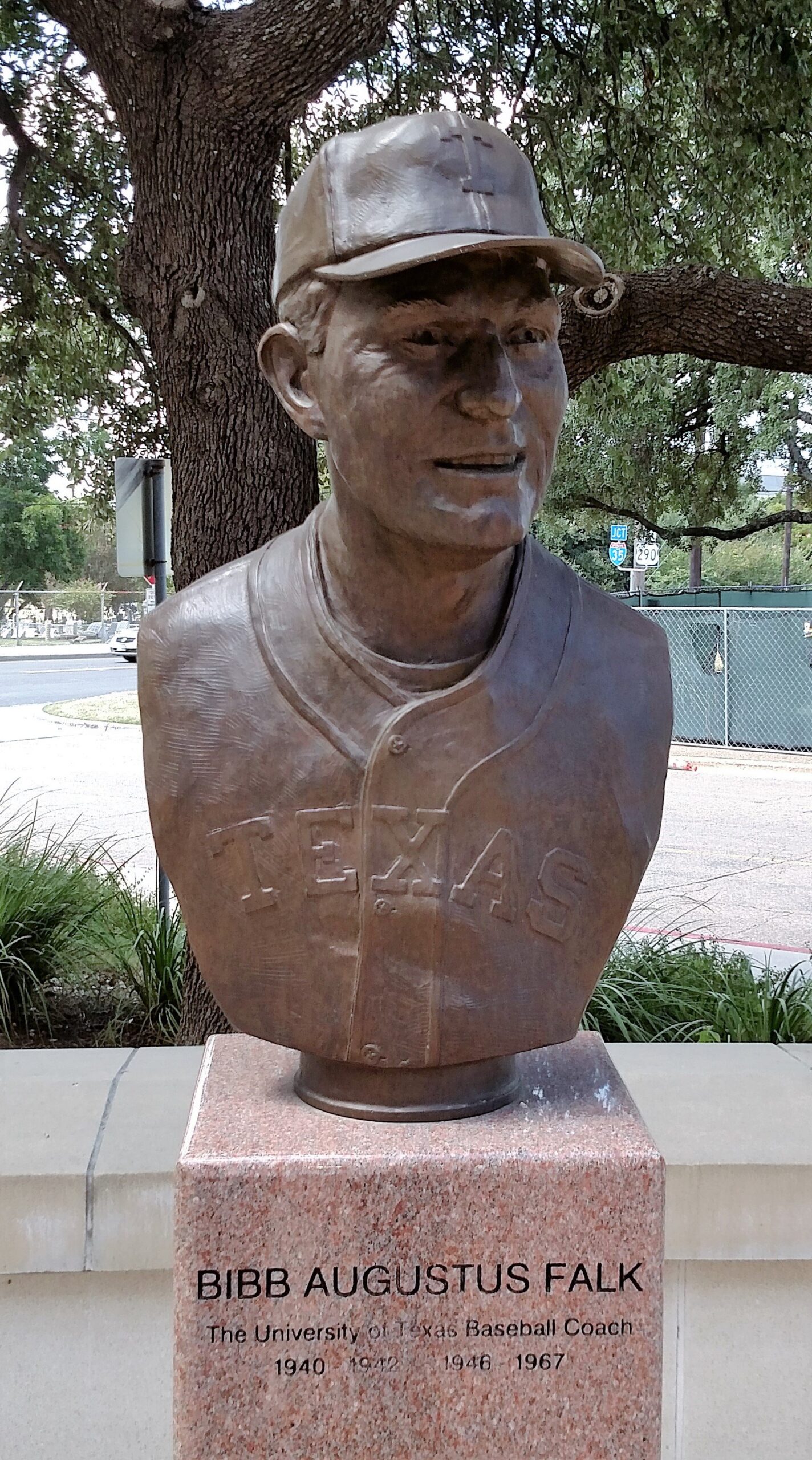

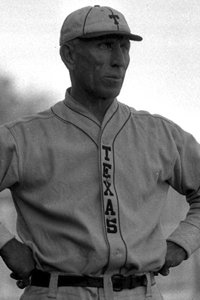

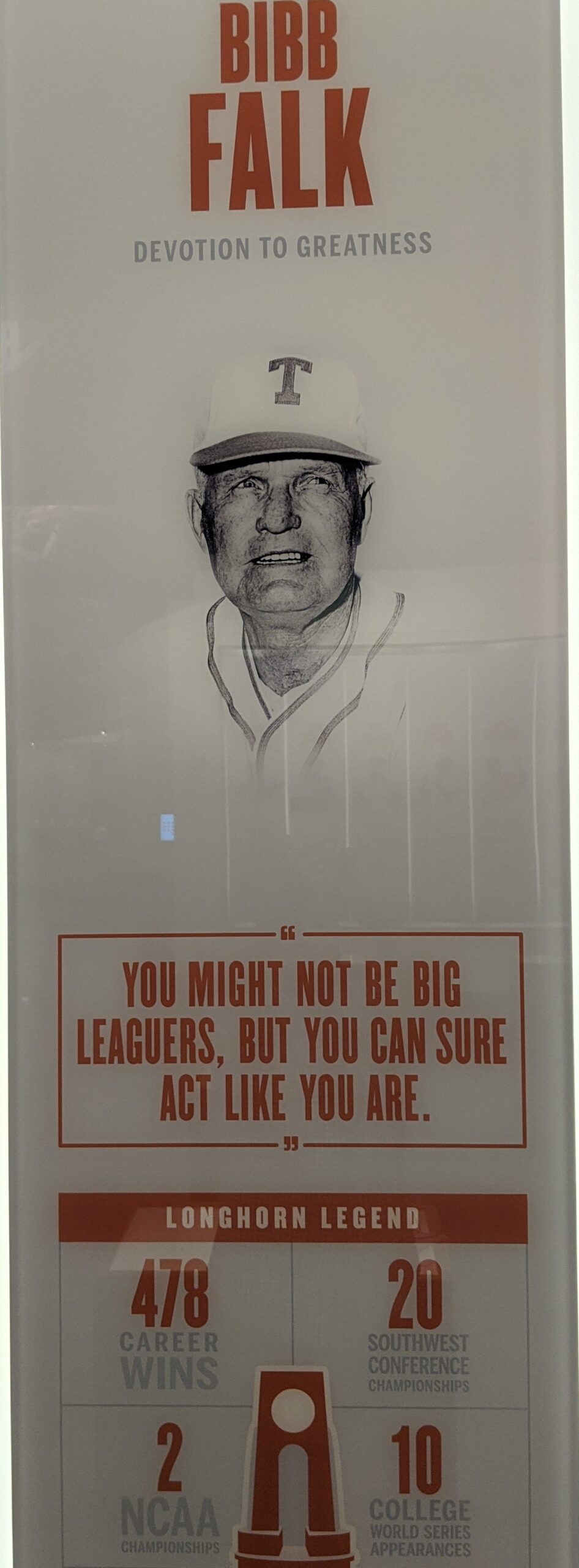

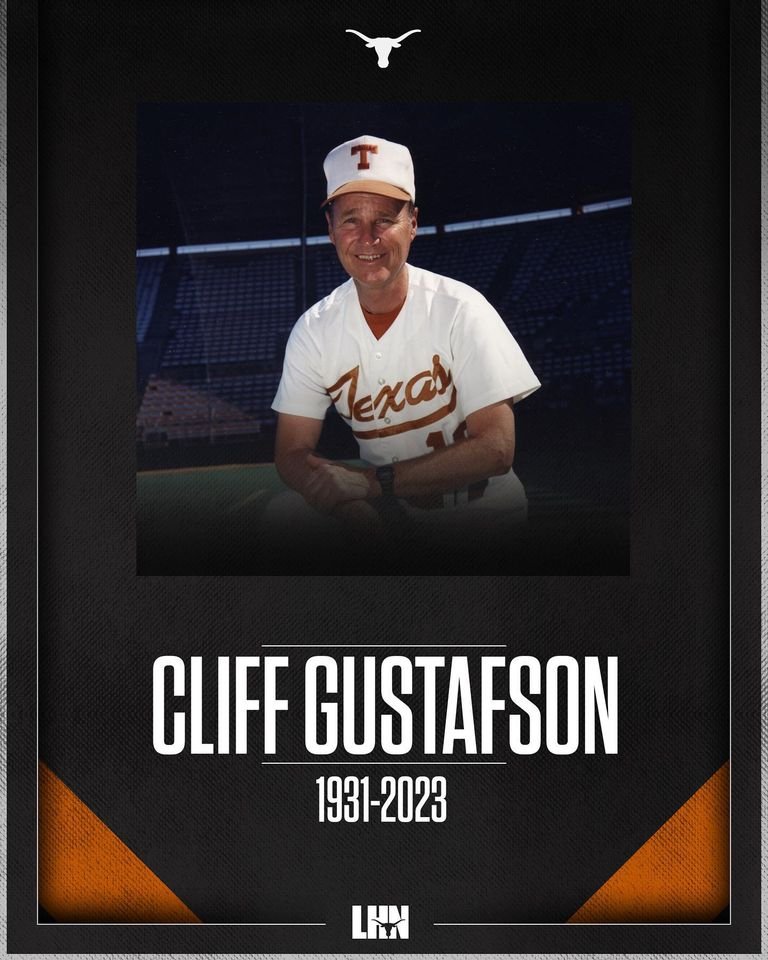

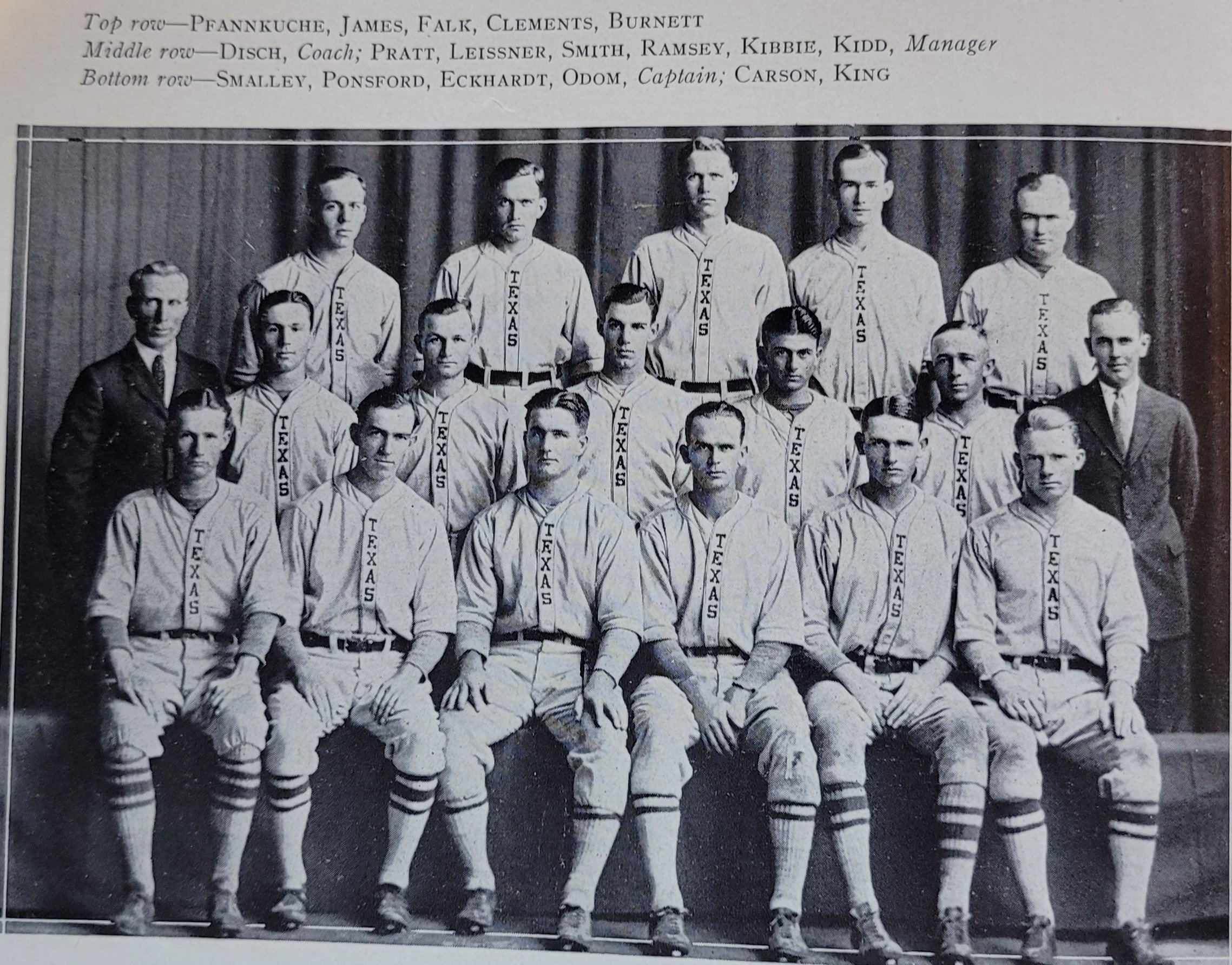

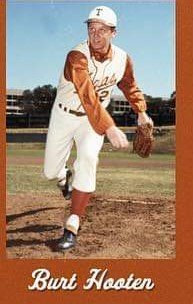

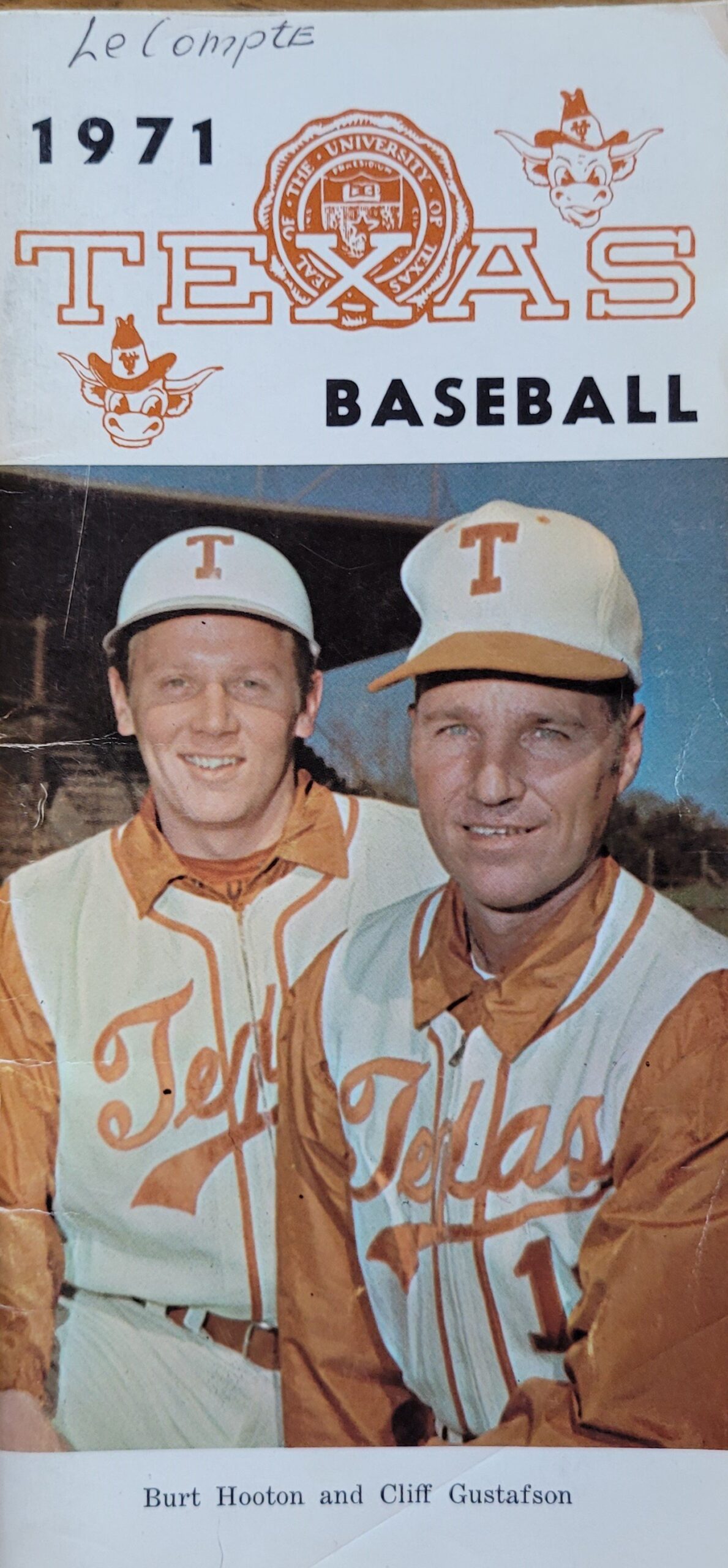

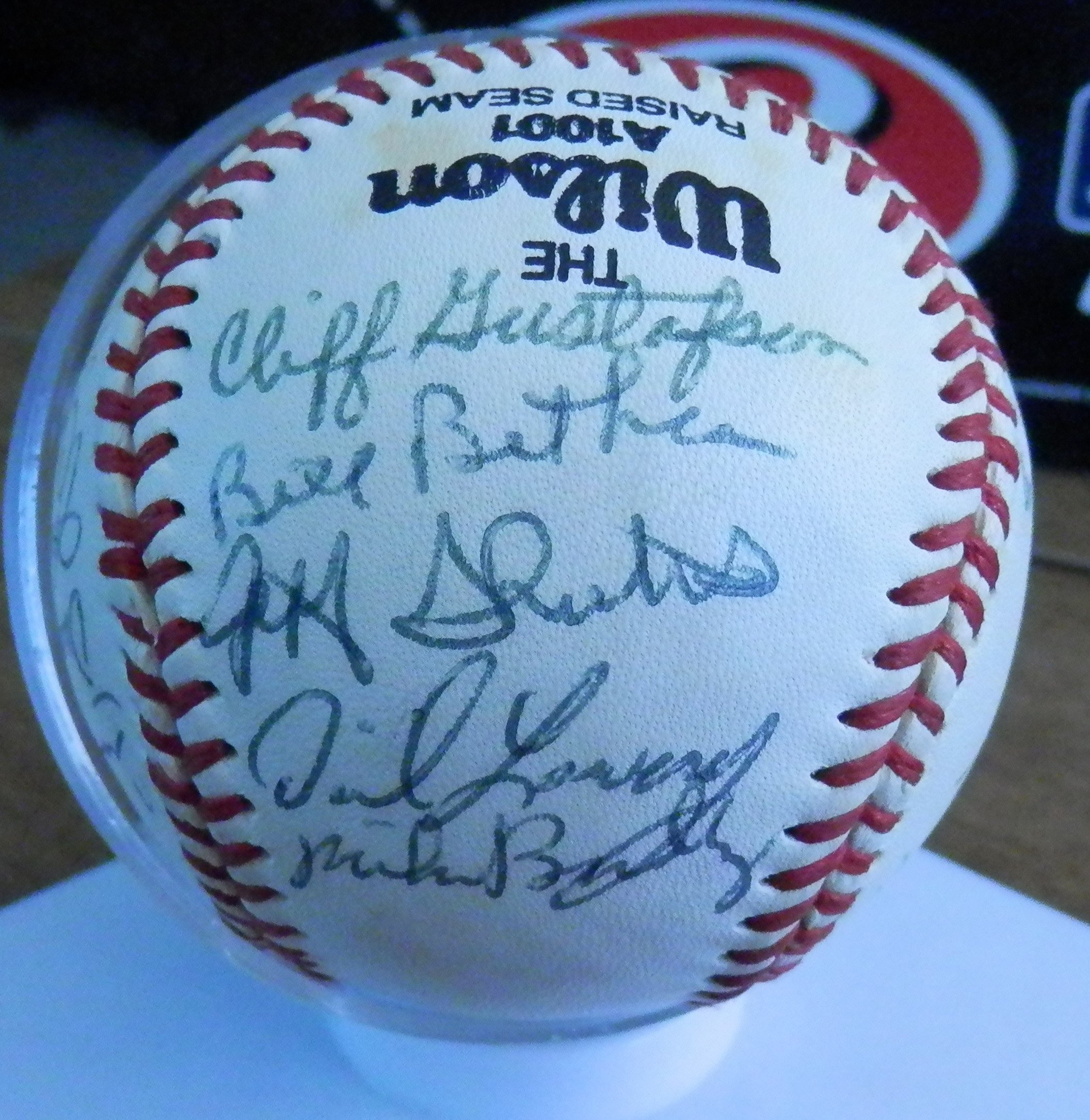

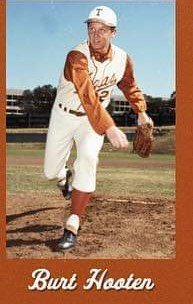

Just a few years after my Clark Field initiation, I would — by then, along with media colleagues — regularly freeze in the breeze whipping the often chilly press box, high atop the grandstand at spanking new and semi-antiseptic Disch-Falk Field, named for the first two coaching gods of UT baseball, “Uncle” Billy Disch and the incomparable Bibb Falk. It seemed perpetually cold in that damn press box until maybe the last homestand each spring. But, boy, did we have fun up there, laughing together and regularly impressed by the talented Texas teams of Cliff Gustafson.

The link to Larry’s article on the three part history of Clark Field is in the red font link below.

1972 CLARK FIELD BY LARRY CARLSON (squarespace.com)

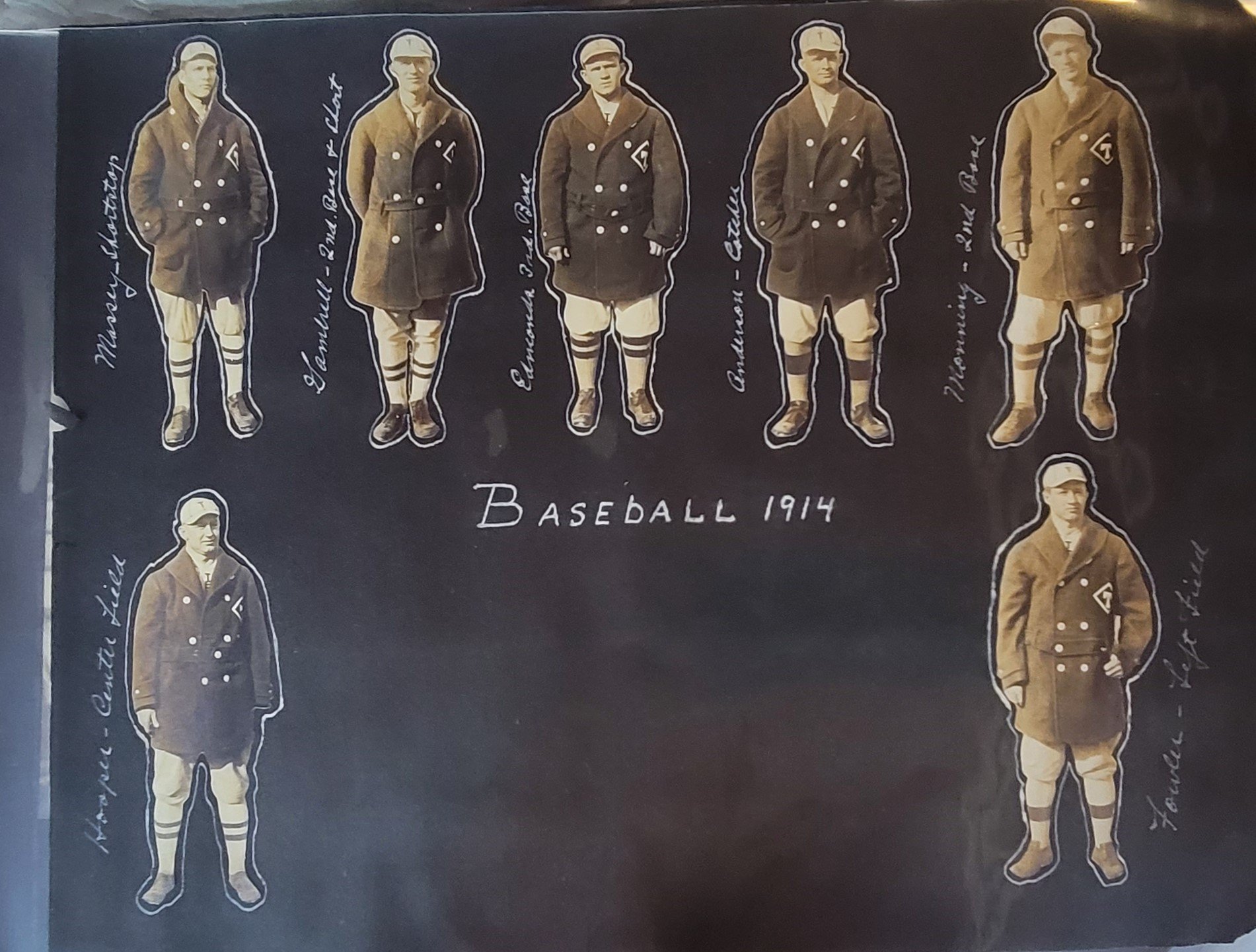

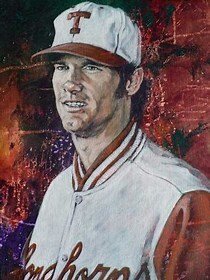

Quick refresher: Disch, born way back in 1872, a century before my first Texas baseball game, won 20 Southwest Conference championships and was sometimes referred to as “the Connie Mack of college baseball.”

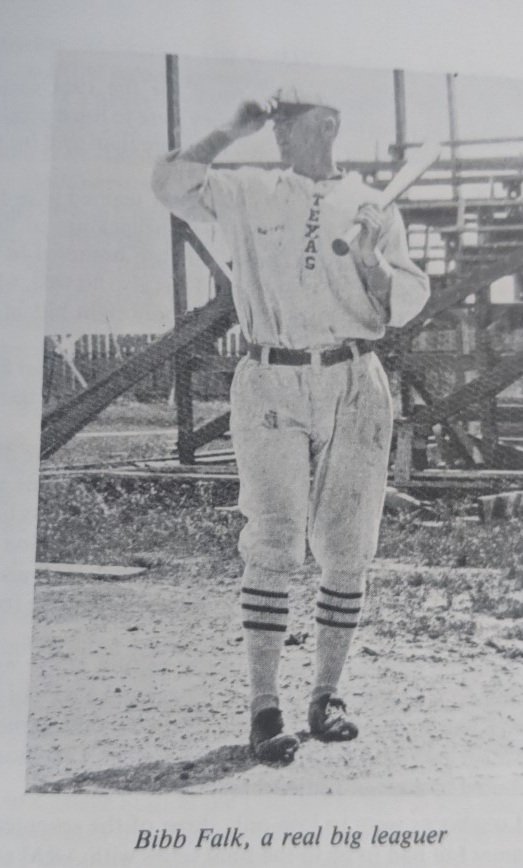

Disch’s best-known pupil was Falk. After killing it at Texas, he played twelve MLB seasons, replacing the notorious “Shoeless” Joe Jackson with the Chicago White Sox after the “Black Sox” game-fixing scandal rocked baseball as it approached the Roaring Twenties. Falk batted .314 in his career with Chicago and the Cleveland Indians. He was close to flawless as an outfielder.

As a coach at the Forty Acres some years later, Falk — like his mentor — led Texas to 20 SWC titles and piloted the Horns to back-to-back national championships in 1949 and 1950.

1928 – Billy Goat Hill

But back to Disch-Falk Field and the 2023 season. I had for some reason been content to keep up with Texas baseball via LHN, radio and newspaper accounts for more than a minute in time. But one of my prized nephews, Wade, phoned to invite me up to join him and my grand-nephew, Elliot, and grand-niece, Lucia, for a game against top-ranked LSU. Wade’s wife, Cathryne, would sit this one out so I could go.

Heck, yeah. Long time, no see, Disch-Falk.

For once, I-35 from San Antonio cooperated. Arriving early, I parked 150 yards beyond the right field wall on 20th Street, hard by Red and Charline McCombs Field.

Mr. McCombs, the legendary UT donor/booster and the epitome of the outsized Texas business entrepreneur had passed away at 95 the previous week. Walking past the cemeteries that border Disch-Falk to the south, I was reminded that the grandfather I never met, Oscar Carlson, is buried there. A Swedish immigrant to Texas in the early 20th century, he died in a car crash when my Dad was just a kid over in Elgin.

Jones Ramsey

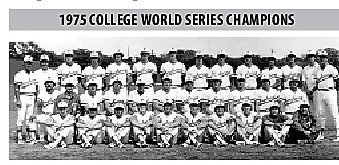

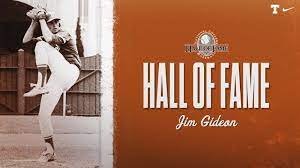

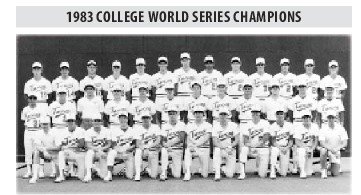

And I thought of how Jones Ramsey, the longtime UT sports publicist of the DKR era and beyond, had made a little joke about Disch-Falk’s location by the graveyards when it opened in ’75. Texas, by the way, promptly rode Jim Gideon’s 17-0 pitching to a national championship, its first since Falk’s repeat a quarter-century earlier.

“A foul that lands over there,” Ramsey quipped, motioning to the cemeteries, “is a dead ball.”

It was worth a good chuckle.

These days, he’d likely be censured or even fired because he was “insensitive” or “tone deaf” about the deceased, at least to those at the ready to be offended. But back in the day, it was just funny. Still is, to me. I mean, Daddy referred to cemeteries as “marble orchards.”

Strolling up to the stadium on an 80-degree late afternoon, I felt somewhat the stranger in a strange land. It just looked different, much bigger. Things are supposed to look smaller than recollected.

Once I met up with the family and we filed in for the last moments of warmups, it all seemed familiar again, in spite of loud bursts of wince-worthy rap and hip-hop blasting through the loudspeakers.

I remembered a favorite restaurant in Florida, just across A1A from the Atlantic Ocean and being delighted to return there several years ago. “Man…it’s good to be back,” I told the host, a complete stranger.

Said he, shrugging and smiling, “You were never gone.”

It’s like that with familiar places, the sights, sounds and smells associated with pleasant memories.

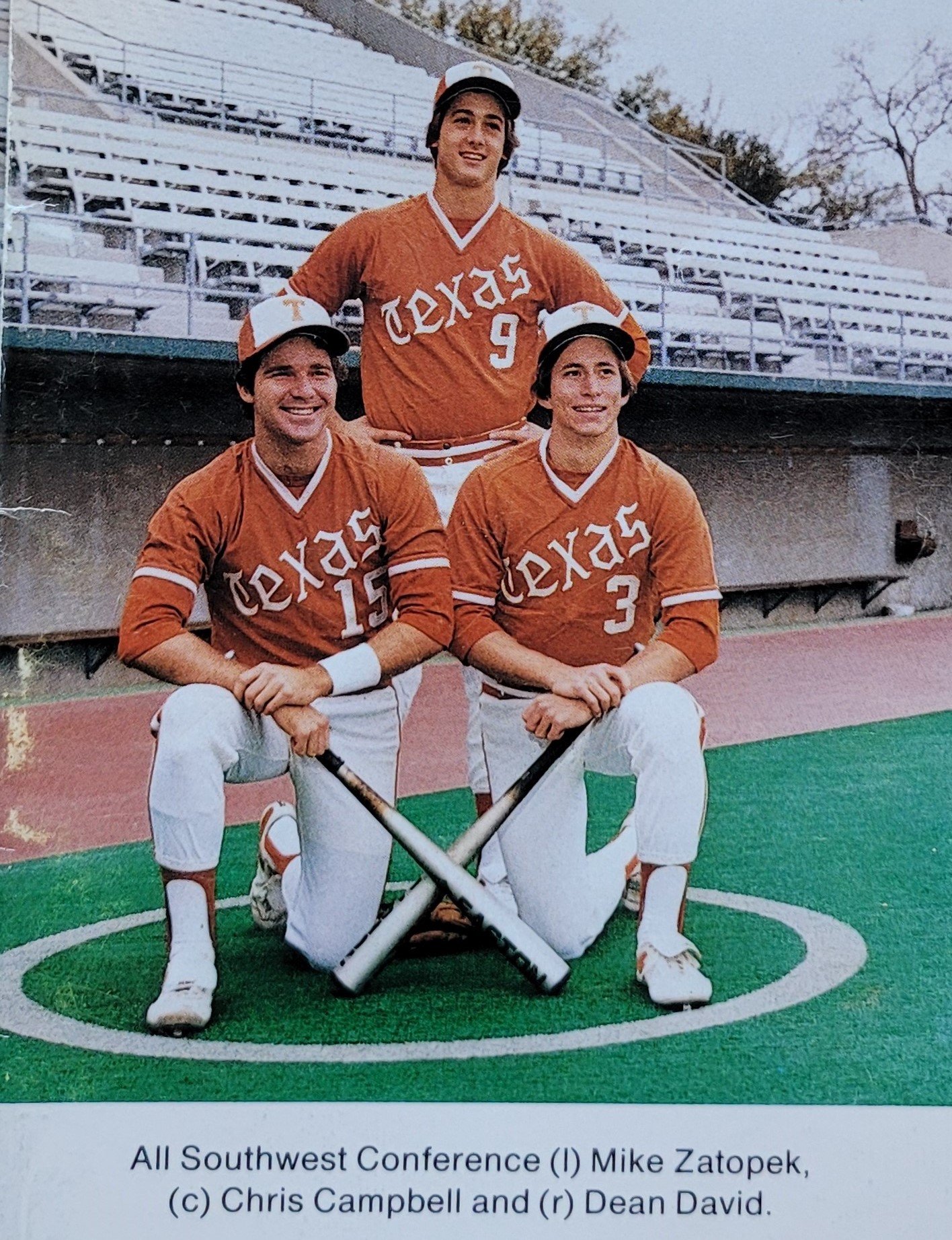

The stadium was only about half-filled as gametime approached. The LSU Tigers were looking spiffy in their yellow jerseys and plenty of eyes were on centerfielder Dylan Crews. The national Freshman of the Year in 2021, he’s now regarded as perhaps college ball’s hottest pro prospect. He hits for average and power and is versatile in the field.

LSU had plenty of fans peppered across the park. Many had enjoyed a super-sized early spring break, the Tigers having participated in the Dell Classic in Round Rock over the weekend. The nation’s number one team had dropped a game against Iowa but had whipped Kansas State and Sam Houston while tuning up for Texas.

It felt a little bit strange to be waiting in line for refreshments when it came time to take off the cap for the national anthem. Not because I couldn’t see the stars and stripes or gratefully doff the lid. But it was the first time I was ordering up a way too pricey Jack Daniel’s instead of a Coke at the Disch.

The menu has evolved at college concession stands the past decade, as we and our wallets know.

Never saw anybody snacking with CrackerJack on this evening, though the now close-to-capacity crowd enjoyed participating in the singing of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” during the seventh inning stretch.

It was still a scoreless tie, the game marked by excellent pitching and defense by the Horns and Bayou Bengals. Remarkable these days in baseball at any level. Refreshing.

Every time Crews came to bat, Tiger fans crooned, “Crewwwws missile…”

He had registered one hit thus far but had not been a big factor.

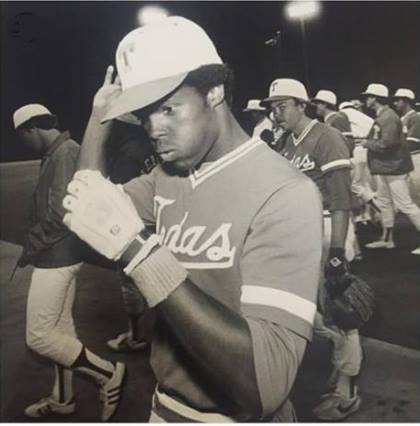

For UT, starting pitcher Lebarron Johnson, Jr had been superb, striking out nine in five scoreless innings.

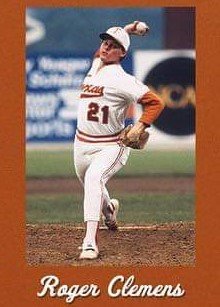

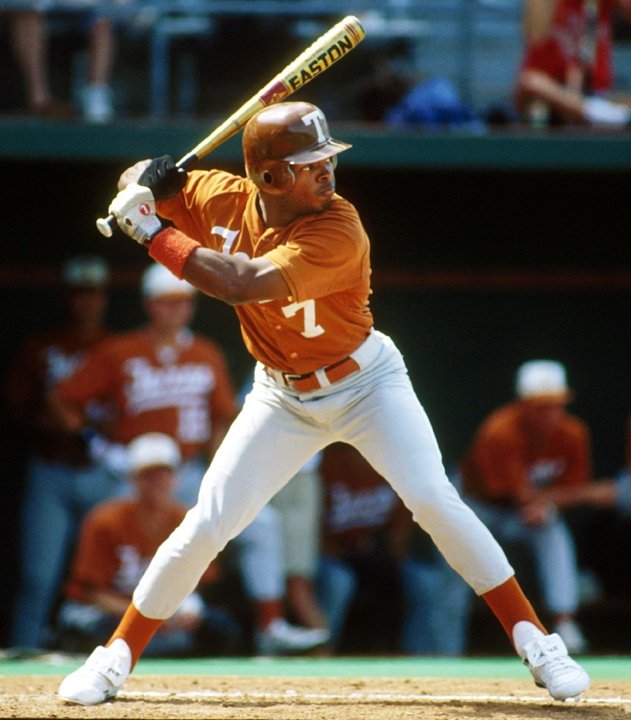

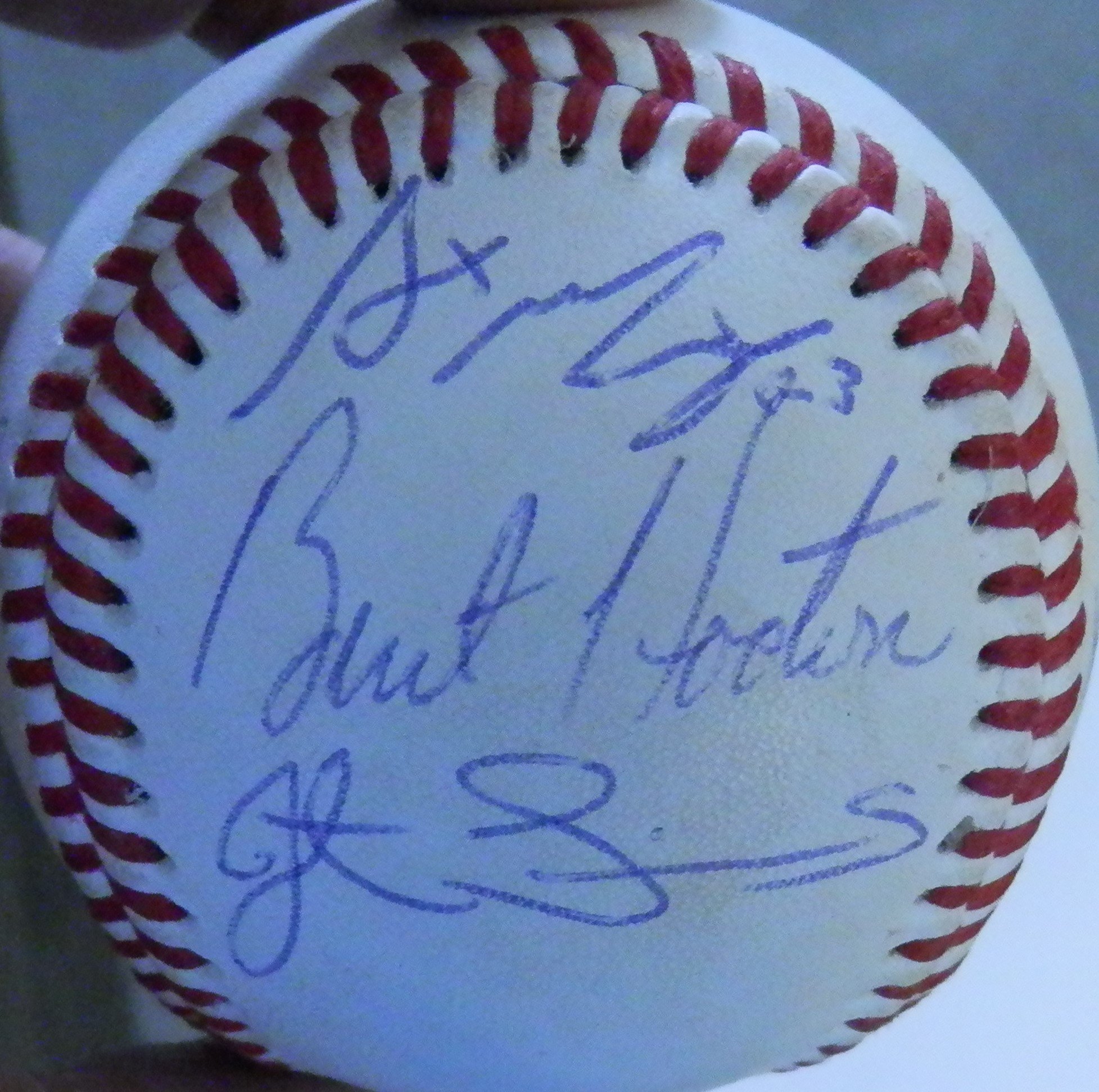

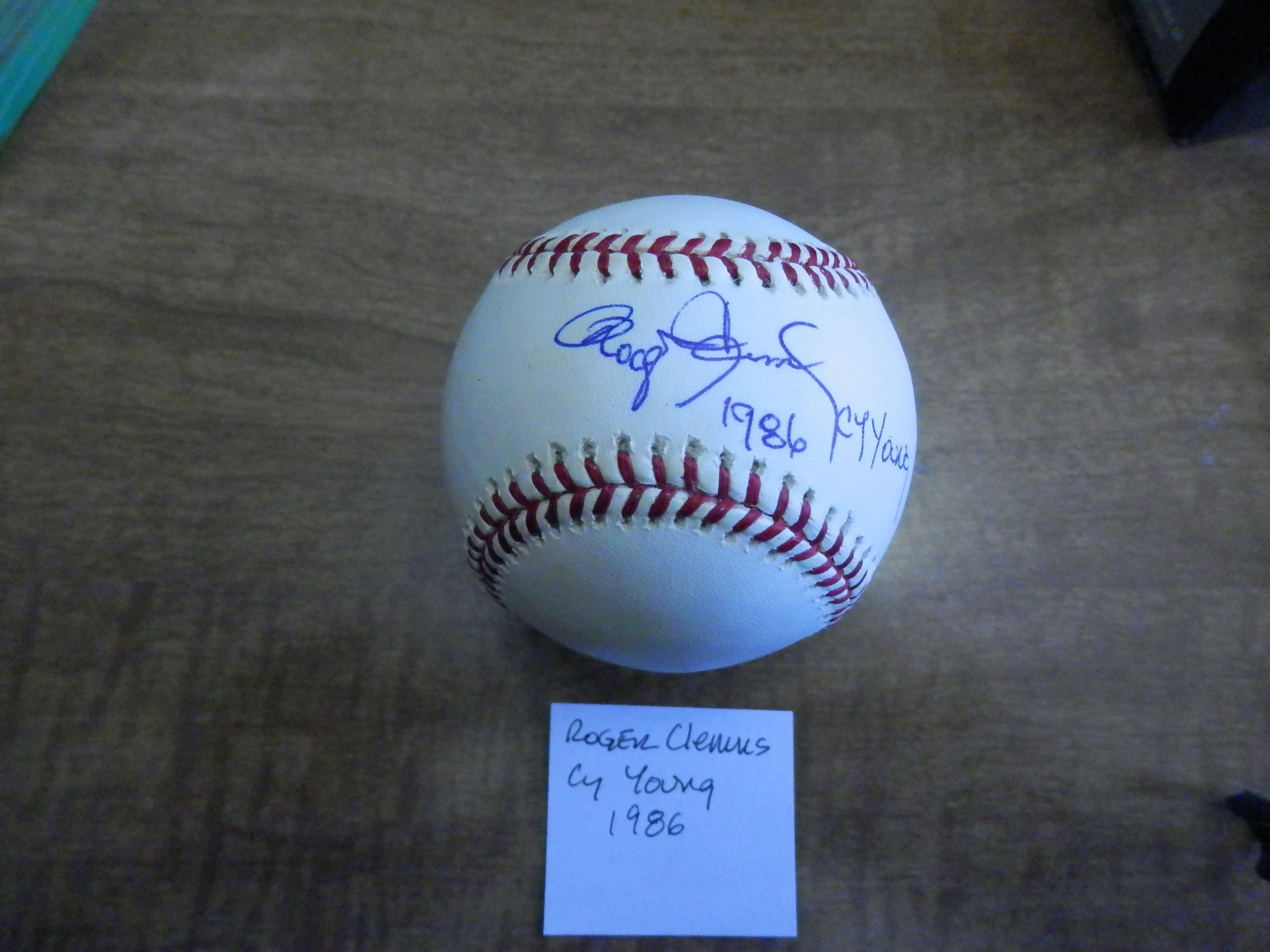

Texas fans were likely wishing super slugger Ivan Melendez, last season’s top collegiate player, could magically reappear and break this tie with one muscular swing. The Hispanic Titanic now plays in the Arizona Diamondbacks organization, though. UT’s biggest highlight — and it was extremely cool — was the laser from centerfielder Eric Kennedy that nailed a Tiger runner expecting to score from second base on a sharp single. Kennedy’s strike had the precision of a Roger Clemens fastball fired from sixty feet, six inches.

Which team’s pitching and defense would at last give an inch? UT’s, as it turned out. LSU got two walks to open the ninth, then a three-run bomb when Crews was on deck. Texas couldn’t answer in the bottom half and a very good college baseball game was suddenly in the books. Cue the trash talk from Tiger fans. Longhorn backers, get ready for the SEC.

Lucia and Elliot

Still, it had been fun to return to the old stomping grounds. To hear “Texas Fight,” if even just the recorded version. To feel the promise of spring and summer on a warm late February night. Wade and I had talked baseball while, as always, cussing and discussing UT football. Lucia told me about her soccer, algebra and reading “Fahrenheit 451.” Little Elliot had brought his glove, regularly called out to his favorite player, right fielder Dylan Campbell, and generally beamed throughout the evening. There was a lot to like about everything, and nothing not to on this night, save for the final score.

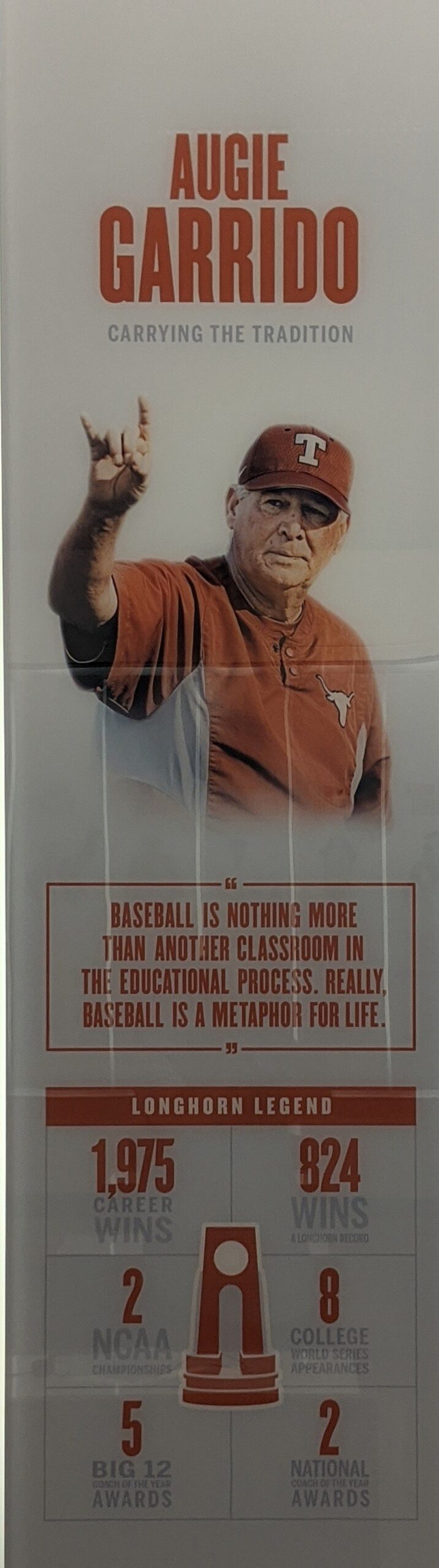

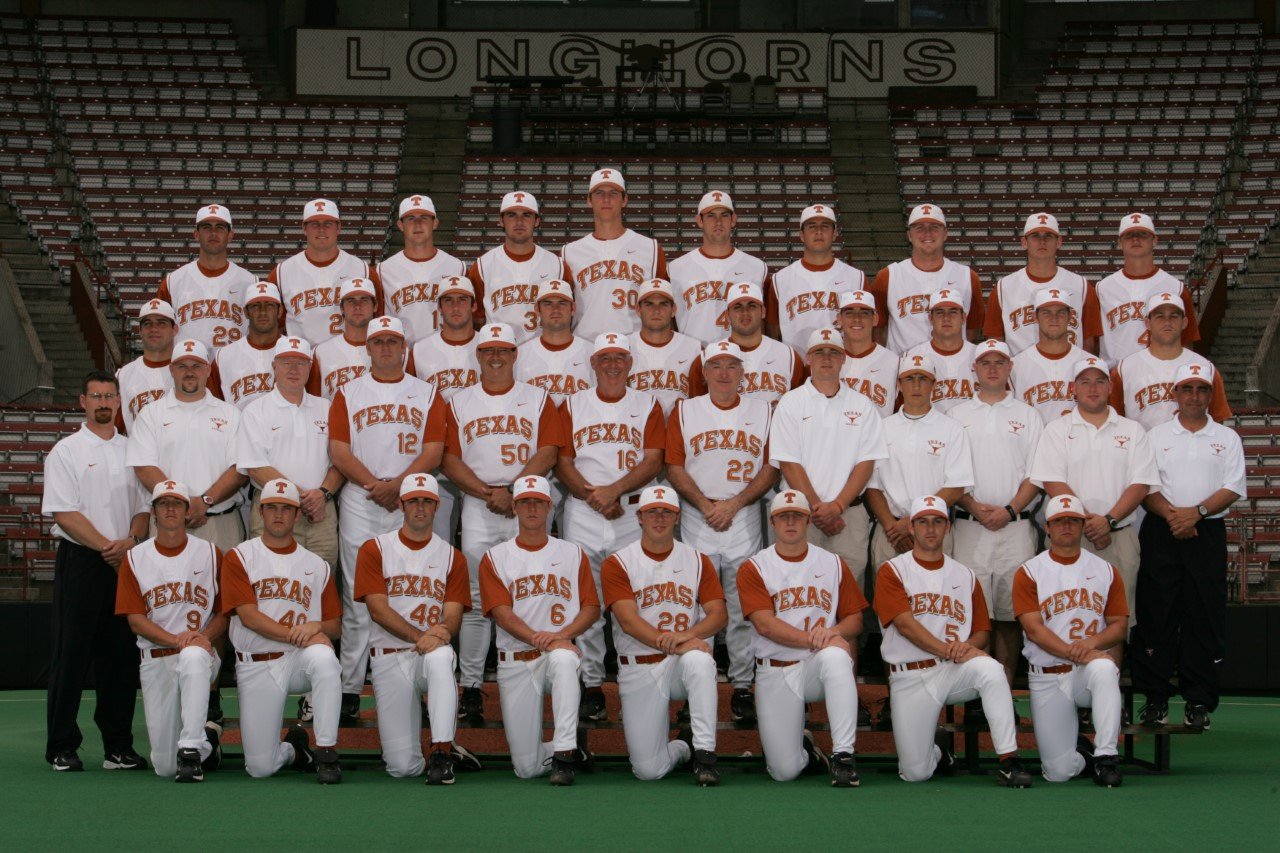

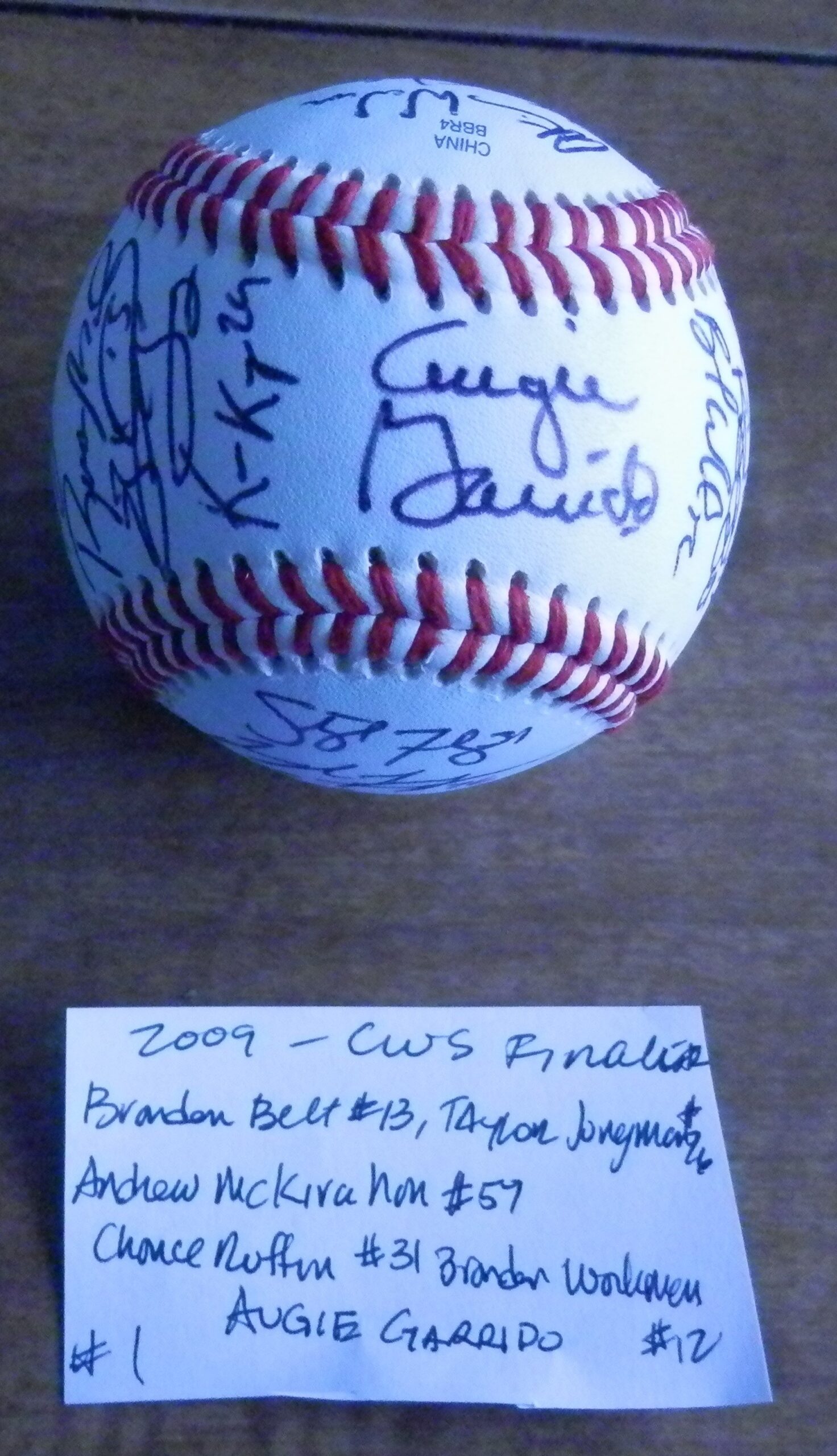

We parted ways, and I stopped just outside the stadium to pay respects to the men now immortalized in bronze busts: Disch, Falk, Gustafson and Augie Garrido. A Texas baseball Mount Rushmore, if you will.

It struck me that perhaps the past, the now, and the tomorrow all co-exist in the brain files and life. Famed Southern novelist William Faulkner addressed that in his often-resurrected take about the past not being dead. “It’s not even past,” he wrote.

Bruce Springsteen essentially put that to music with a stirring line from his notable old song, “Atlantic City,” best performed by The Band singing:

“Well, now, everything dies, honey, that’s a fact.

But maybe everything that dies someday comes back.”

As I strolled past the quiet graveyards en route to my car, I felt no need to whistle or fear the dark.

Striding by the thousands of well-rested souls, with likely a few dead balls nestled in the weeds, I grew a little thoughtful. Momentarily, I pondered baseball, the sport that has always been the sport to inspire and bewitch writers, romantics, and traditionalists, as a metaphor for life.

Yes, there have been switches, developments, shifts, and transitions. Even to Jack Daniel’s and pitch clocks. Still, it returns like hot weather and bluebonnets to comfort, reassure and lend hope to its devoted admirers.