1972 Clark Field By Larry Carlson

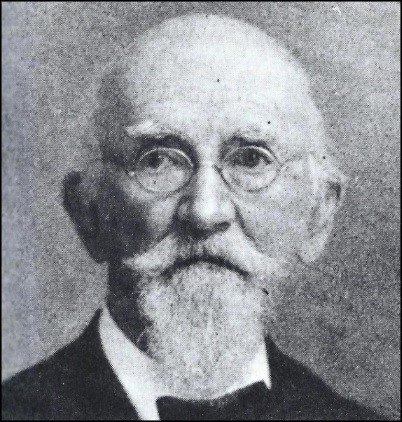

There have been three athletic facilities on the campus named for the university’s influential early leader James Benjamin Clark.

James Clark

Clark Field #1

The first Clark Field, operated from 1887 through 1927 at the southeast corner of 24th Street and Speedway configured for a baseball game. The stands were built in sections and movable so during the football season were configured like the image below.

Clark Field configured for a football game.

Clark Field #2

The second and best-known Clark Field and the one that Professor Carlson remembers was part of Longhorn sports history from 1928 to 1975. Clark Field was unusual because there was a 12- to 30-foot (9.1 m) limestone cliff that ran from left-center to center field which made playing the outfield adventurous. The cliff could only be accessed via a goat path in the left-center field. Centerfield was nicknamed “Billy Goat Hill.” There was a scoreboard on top of the hill in the field in front of the fence that could cause even more weird bounces for outfielders. Clearly, this gave the Longhorns a home-field advantage over visiting teams. For example, the Longhorns could easily get an inside-the-park home run when a ball was hit in the direction of the cliff because the opposing outfielders were perplexed by its caroms and how to make plays by using the cliff. Longhorn outfielders could typically hold batters to a double or triple because of their familiarity with the cliff. Half of the team’s outfielders purportedly chose to play on top while the other half chose to play in front of the cliff.[3]

The Third Clark Field

For 1975 the baseball team moved to their new ballpark, and Clark Field was closed to allow construction of the College of Fine Arts and the Performing Arts Center. Freshman Field was renamed Clark Field. In the 1980s and 1990s, the Clark Field property underwent significant redevelopment, but a portion of the field was retained as Clark Field, a roughly oval-shaped field surrounded by a track near Jester Circle.

LONGHORN BASEBALL: FIFTY-YEAR FLASHBCK TO CLARK FIELD

by Larry Carlson ( lc13@txstate.edu )

I couldn’t believe my eyes when I entered UT’s Clark Field for the first time. It was 1972 and I had witnessed dozens of Longhorn football games across the street at Memorial Stadium. But as a kid riding up from San Antonio with Daddy for pigskin Saturdays had been simple. The vast majority of baseball games at Clark were played on weekdays, starting at one or two o’clock. Access denied.

But now I was a college freshman at SWT in San Marcos, out of classes by eleven on MWF. And with this newly found collegiate freedom, I could opt to skip my Tuesday afternoon Intro to Psychology class with boring, cheerless, and inappropriately named Dr. Merryman. Time for a quick, post-class burger and Manske roll at Gil’s Broiler. Then, if my attractive but very much “used” and mileage-weary, unreliable ’66 LeMans would turn over (looked like Tarzan, ran like Jane), I would hit the road. Back then, I-35 was traffic-free. Time to down those nifty electric windows and crank up the Stones’ latest hit, “Tumbling Dice,” or “Doctor My Eyes,” by a new guy named Jackson Browne. Then I would be exiting for the UT campus in 24 minutes.

Seeing the emerald grass in this real field of dreams, sitting in the splintered seats of the venerable grandstands, watching the Horns warm up with pepper games and hearing the cracks of wooden bats was all very cool. But the coolest part of the setting, hard at first to wrap my brain around, was Billy Goat Hill.

The impressive 12-foot limestone cliff was somehow left standing in the old park that opened in 1928, ranging from right-center field to finally a gentle taper at the left-field line. It provided a picturesque home-field advantage like no other. Paths ran up the hill, where a big scoreboard was situated. All balls were in play, and they were hit there regularly. Longhorn outfielders, of course, practiced their early-day “extreme sports” exercise daily. It was always a marvelous treat to see a Texas player race up a cliff path, pound his glove confidently and camp out under a towering fly ball that would land harmlessly in his glove. Terry Pyka consistently made it look easy

All nature’s amusements aside, and the fact that Ruth and Gehrig had played against UT here, what thrilled me most as a fan was the sheer prowess of the Longhorn players.

It was only fitting of course, that this bunch of young billy goats were led by a guy named Cliff.

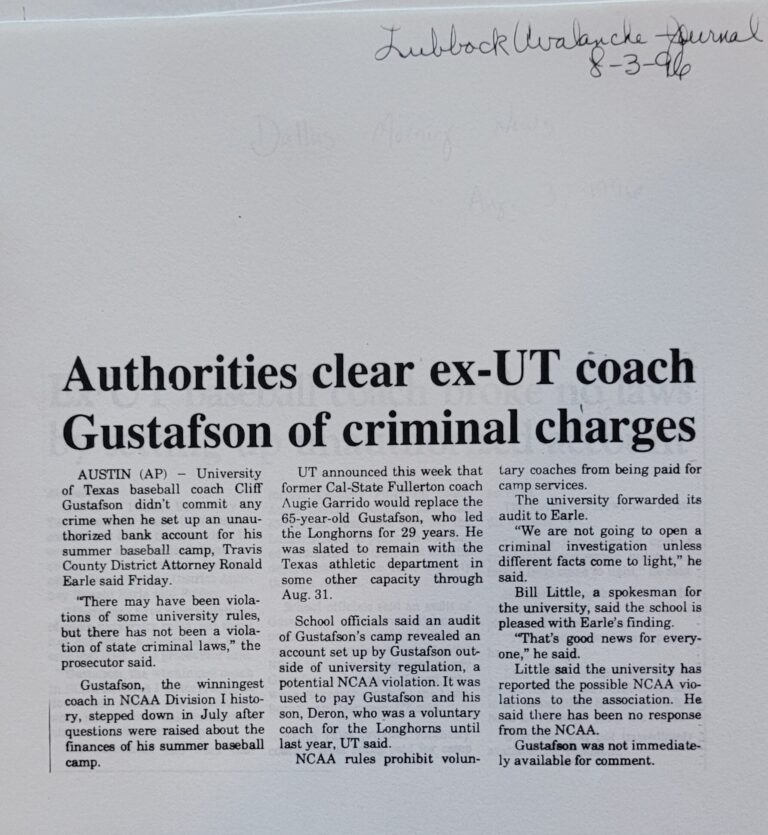

If you grew up anytime around when this old writer did, you might know that Coach Gustafson took a pay cut to move from the powerhouse he had built at San Antonio’s South San High School to take the UT job in ’68.

He would pilot his first nine Longhorn squads to Southwest Conference championships. Seven of those would, remarkably, advance to Omaha for the College World Series, winning it in ’75. Gus would eventually take home 22 conference titles and an unprecedented 17 trips to the CWS, earning another title in 1983.

The Horns of ’72 had lost college baseball’s best pitcher after the ’71 season. The peerless Burt Hooton of Corpus Christi, UT’s first three-time All-American, had gone 35-3 at Texas, and his skills with the patented knuckle-curve would quickly translate to MLB success. While almost all of Hooton’s ’71 Texas teammates were back at Clark Field the following year the newly-minted Chicago Cub threw a no-hitter in his fourth pro appearance that April.

Gustafson, who also would mentor Jim Gideon, Roger Clemens, Greg Swindell, Bruce Ruffin and Kirk Dressendorfer, among others, always considered Hooton the very best collegiate hurler he worked with.

Still, in ’72, Coach Gus had reliable arms in the form of Ron Roznovsky, Martin Flores and Bobby Cuellar.

Catcher Bill Berryhill, from Bartlesville, OK, would lead the team in hitting while fielding his position flawlessly. The infield, in my mind, operated every bit as well as any pro team I watched.

David Chalk

David Chalk had already hit .405 the previous year and was about to close out his Texas days as a four-time all-conference, three-time All-America pick. He was a vacuum at third base and combined a keen eye for average with good power. A future two-time All-Star with the Angels, the Dallas Kimball product was a personal favorite for me to watch througout that ’72 spring. You always hear that term, “rifle arm.” in baseball and football. When Chalk zipped a throw over to first base, it created a pop you could hear in the stands, slapping John Langerhans’s mitt.

The quintessential cleanup hitter, Langerhans — the Ivan Melendez of his day — was already UT’s career homeruns leader.

While Amador Tijerina and Ken Pape more than capably shared time at shortstop, as a San Antonio boy, I found the right side of the infield to be a terrific story. Langerhans and second-sacker Mike Markl were, like Chalk, seniors. They had been together as high schoolers at South San, coached by Gus, and had enjoyed uninterrupted success with their mentor while wearing burnt orange and white. Markl displayed smooth fielding skills and a steady and productive bat. Langerhans, later a longtime coach at Round Rock, always had an impressive chaw in his cheek and the lefty leaned way back in the batter’s box, ready for a pitcher’s mistake. Big John had power anyway, but the short, 300-foot right field porch looked mighty tempting on those sunny spring afternoons. The quintessential cleanup hitter, Langerhans — the Ivan Melendez of his day — was already UT’s career homeruns leader. The ’72 squad was somewhat of a San Antonio all-star team under Gus, featuring Langerhans, Markl, Pyka and Pape.

Mike Markl

Clark Field’s campus location encouraged and enabled plenty of UT students to drop in, at least for a few innings between afternoon classes. A lot of witty, on-target heckling was aimed at opposing players and coaches. I don’t recall any profanity coming from the early version of the famed Wild Bunch. But they could find the smallest physical flaw in an opponent’s appearance or gait, and the best barbs flew with machine-gun rapidity when the despised Aggies came to town to close the regular season. Watching the Horns dispatch the Ags en route to another SWC crown (albeit one shared with TCU) was as sweet as one of those ice cream cones over at Sandy’s on Barton Springs Road.

With Texas headed for the playoffs again and me having passed all those freshman classes, I got an extra treat as I moved back to my parents’ San Antonio home for a summer job as a lifeguard (It wasn’t the dream job I had expected; I was merely one of the state’s most lightly-paid babysitters). The Regionals would be hosted by San Antonio. Excellent teams from Trinity and Pan-Am (now known at UT-RGV) would face off against UT in a three-team, double elimination tourney at VJ Keefe Field on the St. Mary’s University campus. I vividly recall meeting my Dad before the game, over at the big annual barbecue held by his friend and business associate, Mr. Ray Ellison. I had known Mr. Ellison since I was a kid and had accompanied Daddy to many editions of the barbecue, a couple of times wearing my Little League baseball uniform and getting a strong “pre-game” meal prior to heading to the sandlot.

From left to right Larry Carlson, Ray Ellison, and Everett Carlson UT 1947

So now, as an 18-year-old who could still burn ten thousand calories per day, I polished off two or three plates of brisket, sausage, tater salad and beans and thanked Mr. Ellison before taking off to watch my team play a crucial playoff game in my own hometown.

Texas won a tense 14-inning game that night, at last pushing past the Trinity Tigers, 4-3. It turned out to be foreshadowing for the tourney. The Longhorns’ pinpoint pitching would prevail, but only after scratching out two more one-run tests against Pan-Am, winning 1-0 and 2-1. Only four runs allowed in 32 innings. Next destination for Texas would be the Horns’ “home away from home,” Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha.

A week later, the Steers — aiming for their first CWS title since 1950 — were stunned by the Cinderella team of the tourney. Connecticut silenced the UT bats in a shocking 3-0 upset. And then the losers’ bracket game with Ole Miss somehow looked even uglier, Texas falling far behind early on. Broiling at the lifeguard stand, I had to leave the radio to a co-worker while moving to the “wall” station at the pool while my beloved team appeared to be closing out the season with a whimper.

I was drowning my sorrows with a frosty Big Red from the lifeguard team’s communal ice chest, when I got back on duty at the main “tan stand.” The burnt orange bats, slumbering in four playoff games, had awakened in timely fashion. Somehow, Texas overcame a huge deficit and eliminated Ole Miss, 9-8.

On deck, the next foe up in the losers’ bracket was football arch-rival Oklahoma. UT’s pitching prowess returned while the bats stayed hot as the Longhorns blasted OU, 7-1.

Suddenly, Texas was back where it was supposed to be, alive and peaking, in the semi-final field along with the other two members of baseball’s big three, USC and Arizona State, plus an outlier, Temple.

Alas, the fairy tale comeback ending would not happen. Rod Dedeaux’s Southern Cal team squeezed past Texas, 4-3, in ten innings to move on to a title game against ASU. The USC lineup featured Fred Lynn, who would be the American League MVP for Boston just three years later. The Men of Troy whipped the Sun Devils for their third straight national championship, en route to five straight.

The collective heart of Texas’s team for four years, Chalk, Langerhans and Mark,l had completed their eligibility and were headed on to professional baseball. But in ’73 a re-built UT squad would determinedly return to Nebraska with a shot at the elusive national title. Again, though, Southern Cal would prevail. The same thing re-occurred in ’74. And this time, Texas having played their final season at quirky, wonderful Clark Field, UT would lose twice to the Trojans. The frustration, amid marvelous success, was unnerving for Longhorn players and fans.

Southern Cal’s seeming iron grip on the trophy ended in 1975. Led by a masterful pitcher who had been a freshman on that stout ’72 Texas team, UT wrested the title away for the Horns’ first hardball national championship in a quarter-century. Jim Gideon, with a mind-boggling 17-0 record on the hill, was the toast of college baseball. Indeed, Texas had inaugurated its new home, Disch-Falk Field, across I-35, in impeccable style, having claimed all the marbles. “The Disch” was absolutely more spacious, certainly more modern and spiffy than UT’s creaky, graying home of the past. Concessions and restrooms were plentiful, as were parking spaces, at least to an extent.

But to some die-hards, the spanking new, somewhat antiseptic surroundings could be no substitute for cozy Clark Field and Billy Goat Hill.

Crushed by bulldozers in the name of modernity and progress, the long-gone lair of the Longhorns lives on in the memory banks of its admirers. There, the one-of-a-kind monument to a different time endures lucidly, its unmatched architecture and ambience intact.

TLSN TLSN TLSN