Billy Dale’s Self-portrait

The Inner Wounds From Sports Injuries

by Larry Carlson

The strong impact of athletics upon so many Americans cannot be understated.

Most of us who participated in athletics in high school benefited from the experiences that came with it. Commitment. Camaraderie. A sense of belonging and of accomplishment. Still, there was adversity to overcome. Some physical pain, some mental stress tagged along for the ride.

If we weren’t scarred ourselves, each of us has known others shaped by injuries that stayed with those friends and teammates, sticky fly traps attached to the soul.

To some, the sports setback came at a higher level than high school, in college and perhaps even in the professional ranks.

Across all arenas of life, including love, work, faith and family, we are tested. Those tests can be so stressful as to potentially bend or break the human spirit. Sometimes for years, occasionally a lifetime. The higher up the food chain of athletics, with more steep personal stakes, the effects of sports injuries can be profound.

In many cases an injured athlete becomes – to coaches and to himself – less than part of the team. Are you injured? Or are you just hurt? “You can’t make the club in the tub.” That’s the age old warning to athletes, not to frequent the whirlpool or the trainer’s room. Too many athletes at all levels, through no fault of theirs, become pariahs in the locker room and in the eyes of their coaches. Some are no longer counted on, moved away from practices to “walk laps” on crutches. Many sense that they are quickly dismissed as “disposable.” Often, the injured individual’s biggest obstacle to overcome is his own sense of value, his identity as a contributor, as a teammate.

Suddenly, oftentimes forever, a young athlete sees his self-image eroded.

Many of today’s college athletic departments provide sports psychologists on staff to deal with the mental make-up of each player. But great numbers of athletes mask their feelings and succumb to the risk of temporary or lasting depression triggered by injuries. Unwarranted shame and a fog of doubts frequently erase confidence and tenacity. The mental shrapnel from physical damage crowds out the self-esteem supplied by one’s identity as a crucial cog in the machinery of a sports team. Replacements for players are found, teams move forward. Those warriors who feel left behind can carry serious psychological baggage as they begin to navigate life after athletics.

When I heard such a poignant tale in person several summers ago, it came as a surprising gut-punch. I had come to know and like and admire my new friend, Billy Dale, the CEO of Texas Legacy Support Network. Many years earlier, the same Billy Dale had played a role in greatly disappointing me as a 12-year-old. You see, he helped lead his Odessa Permian Panthers past “my” San Antonio Lee Vols, 11-6, in the state championship football game. I forgave that star player, at least somewhat, when he signed on with Darrell Royal to play for the Texas Longhorns.

Now, here I was, eating lunch with Billy in San Marcos one June afternoon, and he shared with me a very personal narrative about his playing days at UT. I could hear the pain in his voice, see the hurt in his eyes, as he recounted a long struggle borne of self-exile brought on by an injury his senior season. I could hardly believe my ears. To think that ol’ number 22, the guy who crashed into the end zone late in the Cotton Bowl game on 1/1/70, to enable national champion Texas to beat Notre Dame, could ever, ever feel that he had somehow not measured up to his expectations was astonishing. To hear that he felt he allowed an injury to betray his teammates/brothers and coaches because, in his eyes, he then did not fill his football potential in the autumn of 1970, I hurt for him.

But Billy’s story was one that is easy for so many of us to identify with. If it can’t quite be classified as universal, well, it lives in the same damn neighborhood.

Disappointments haunt us all. But Billy Dale, as I already knew, had come out of the tunnel of darkness into sunshine again, into the love of family, friends, business associates and, of course, old teammates dating back to junior high.

His long, winding trail is one well-traveled, bearing many footprints. When you read Billy’s heartfelt account, perhaps you’ll see traces of your own. I saw mine.

Billy Dale’s Self-portrait

Norman Rockwell painting his self-portrait

While the saying “a picture is worth a thousand words” rings true, very few pictures capture a lifetime of words. I have such a painting nicely framed in my office. It’s a painting completed in 1970 that I didn’t know existed until 2014—a painting of a football play inspired by the perspective of former Longhorn football player and renowned artist Ragan Gennusa.

While the story shared by this painting is personal to me, it’s important to note that recovering mentally from a sports injury is part of the lives of many former student-athletes. Every year, countless athletes experience injuries that permanently alter their life path. My story is only one of many.

A player from the mid-1960s football team called me in 2014 and said,

“Billy, I bought a painting from a rancher in South Texas during an auction, and I’ve had it hanging in my house for years. The other day, I was looking at it and noticed that the running back had a pug nose, and I thought it might be you. If you want, I’ll bring it to your house, and you can have it if the runner is you.”

It was me.

The first time I saw the painting, it overwhelmed my senses, reminding me of the journey I’ve been on since the renowned artist Ragan Gennusa painted it. The painting serves as a reminder of the challenging transition from the person I was to who I am in 2024.

Ragan’s paintings hang on many walls and hallways on The University of Texas campus. Here’s a montage of some of his work and a link to the Texas Legacy Support Network’s (TLSN’s) interview with Ragan in 2021.

https://www.texaslsn.org/ragan-gennusa

In the painting below by Ragan Gennusa, there is a depiction of Longhorn center Jim Achilles blocking for me during a 20-yard run in the UCLA game. However, the run was nullified due to a forward lateral. I replicated the painting and brought this cherished moment to Jim at his home in Austin (may he rest in peace). When I asked him why he was looking back instead of ahead for someone to block, he jokingly replied, “I thought someone might catch you from behind because you were so damn slow.”

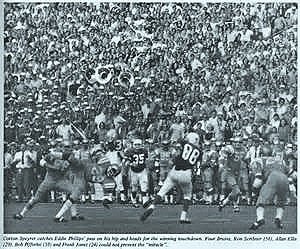

The date was Saturday, October 3, 1970, at Memorial Stadium in Austin, TX. The game kicked off at 4:00 PM CDT. Yes, this run was in the game that Texas won on a Phillips-to-Speyrer catch in the last seconds to keep the Longhorns’ winning streak alive.

Eddie’s throw and Cotton’s Catch

Eddie’s Throw to Cotton

On Cotton’s catch that won the game, I was lined up on the right side and ran a 10-yard hook inside as a decoy or as an alternate receiver in case Cotton was not open. I was not too far from Cotton when he made his miraculous winning touchdown catch.

Realizing the significance of this moment a split second before the fans did, I glanced at the stadium’s East side to capture their reactions.

#88 Cotton’s catch

Cotton’s run to the end zone

The fans, who had mentally prepared themselves for a loss, were now celebrating as winners. The stadium was filled with a sonic boom explosion of screaming, joy, and pandemonium. The emotional release was so intense that those of us on the field celebrating the moment could not hear our own screams of joy.

Refelction Point by Billy Dale

It’s inevitable that each of us will reflect on our life journey at some point. This pivotal moment allows us to see the highs, lows, and challenges we’ve encountered in a panoramic view—a reflection point. The image below captures this moment of contemplation. My reflection point occurred in 2014.

When I first saw Ragan’s painting in 2014, I was overwhelmed by personal emotions elicited by the moment depicted in the 1970 painting. It was an epiphany moment for me. As I looked at the painting for the first time in 44 years, being part of winning the UCLA game was the last thing on my mind.

The contrast between who I was in 1970 and who I’d become in 2014 overwhelmed my senses. The painting reminded me of the complex tapestry that shapes boys into men. The image I looked at celebrated victories, exposed failures and vulnerabilities, shared humor, and ultimately led to the transformation of a young man who was once burdened by insecurities and fear of failure.

Fear of failure is a paralyzing condition that hides deep-seated anxiety, thereby making it hard to embrace challenges, experience setbacks, and still grow mentally and learn from the experience.

Psychologists say that failure is a critical component in learning and character development. Living life with a fear of failing usually thwarts an individual’s mental and social development and, by extension, reduces their quality of life. To paraphrase Yoda, “You want to know the difference between a Master and an overachiever with a fear of failure? The Master has failed more times…. and learned in the process.” The point is that you can’t master life and enjoy all its precious qualities living a life controlled by fear of failure.

The UCLA game is my reflection point

1970 backfield – Phillips, Dale, Worster, Bertelsen

On the game’s second play, an official sports publication says,

“Texas halfback Billy Dale found himself in the thick of the action. As quarterback Eddie Phillips pitched him the ball on an option play, a UCLA linebacker delivered a bone-crushing hit. The result? UCLA recovered a fumble, and the battle was on!”

It was a fumble, but I never touched the ball. Eddie lateraled the ball to a spot where I was supposed to be. However, the crushing hit before Eddie’s pitch left me lying on the field—barely conscious with a hurt shoulder. The trainers rushed to my side, and after a few minutes, I managed to walk off the field under my power.

In 1970, there were no concussion protocols. Getting knocked out was euphemistically called “getting your bell rung.” While my bell rang, the team doctor came over with his pen-sized flashlight and asked me to follow the light with my eyes. My eyes passed the light test, and it was determined that I had no severe brain damage even though, at the moment, I don’t think my brain agreed with the diagnosis. This hit was my fourth bell-ringing incident since high school, but in each case, I recovered quickly and finished the game.

On the sideline, Head Coach Darrell Royal asked if I could still play, and I said “yes,” but I told him that “my shoulder felt numb.”

Dale and Phillips

Dale, Royal, and Bertelsen

The Day After the UCLA Game

I couldn’t get out of bed the next day. My pain level was a nine on a ten scale. My roommate, Julius Whittier, called Longhorn Athletic Trainer Frank Medina about my situation, and a visit to the team physician followed. I was diagnosed with a separated shoulder. This injury was my first football-related severe injury since the 7th grade, and I didn’t know how to handle the bad news. It was the first time I realized that my football career was likely over, and I was unprepared for that. I fell into depression.

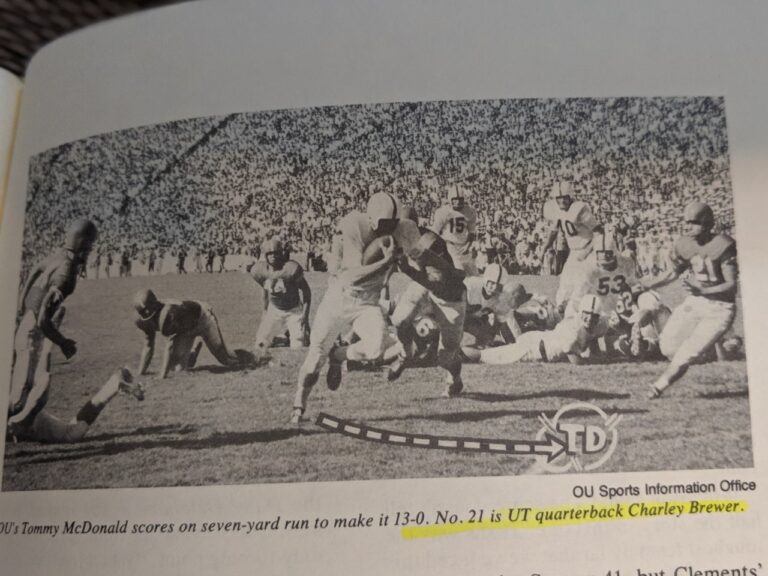

I attempted to play in the (OU) game the following week. However, my shoulder was taped so tightly that I had difficulty catching laterals and fumbled the ball on one play. After the fumble, I knew I was a liability to the team, and when Coach Royal on the sideline asked me if I could play, I said, “No!” Not playing against OU was the lowest point in all my years of playing football, and the game profoundly impacted my self-esteem. My immaturity was exposed.

I never fully recovered from the shoulder injury in 1970 but eventually healed enough to contribute to the team. However, I still don’t remember playing in games or reviewing game films after the Longhorns played OU, but plenty of game films show me blocking and running on the field.

I made mistakes by not planning for life after football.

After the 1970 OU game, I realized for the first time that I had chosen to live a one-dimensional life focused solely on football and neglected the challenge of personal growth in other areas. The shoulder injury robbed me of my football player identity, and I had no backup plan. The painting serves as a reminder of my state of mind and the difficult journey that followed to redefine myself. Even though I’d received my marketing degree, I left college with no marketable skills; therefore, I worked menial jobs, such as filling vending machines on a night shift and working as a fast food cook. My dad always reminded me that I needed tools in my resume toolbox to succeed, and these menial jobs were necessary for my toolbox.

Dad was right! My resume toolbox was empty, but it would not stay that way. It took a few decades, but I finally filled my toolbox, discovered my true passion, and regained my self-esteem.

However, my most crucial memory, evoked by Ragan Gennusa’s painting, is the most important. Psychologist and author, Adam Grant shares, thought-provoking wisdom about coaches’ influence on boys turning to men. He says:

“For athletes, coaches are Godsent. They teach young souls discipline, goal setting, and teamwork. These qualities taught and learned lead to a life with purpose and the strength of character to overcome adversity.”

I wholeheartedly concur with Adam! Although I lacked most tools in my youth, I always possessed a crucial asset Adam Grant mentions: discipline. More than IQ or innate talent, discipline is the fundamental tool necessary for a successful quality of life.

Discipline is the cornerstone of my life journey, and Ragan’s painting poignantly reminds me of this vital aspect. My work ethic nurtured by discipline symbolically enabled me to run again, as I did in 1970.

HORNS ???? UP

Billy Dale