SWC- Death by Suicide

There were no poker faces in the SWC.

Many sports professionals believe that two reasons for the demise of the Southwest Conference occurred in the 1980s. One was the upstart ESPN, which negotiated long-term contracts with college teams promising to enhance a college team’s brand. Since ESPN offered no money, initially, the Southwest Conference rejected the offer, saying it wanted money upfront. Other sports professionals thought the conference’s demise began in the 80s when SMU, TCU, Texas A&M, and Houston all went on NCAA probation for recruiting excesses.

In sports writer Dan Jenkin’s book “I’ll Tell You One Thing” he writes:

The southwest conference officials felt like they were being picked on for recruiting infractions, pointing a finger at Florida State and Miami who had reputations for illegal recruiting but no NCAA punishment. Many professionals with tongue in cheek said that a game between these two teams should start with a burglar alarm.

In truth, the SWC got caught more often then other conferences because they were sloppy recruiters bragging to others of athletes signed and stupid enough to actually confess to infractions.

Gordy Brown

The SWC reached national prominence in 1927 with heralded players such as Rags Matthews, Joel Hunt, Gordy Brown, and Gerald Mann, but even with this SWC climb to national prominence, a cliff to demise was in the future.

The SWC – death by suicide by Billy Dale, with a notable assist from some great authors

This is a long article, so a table of contents is completed from top to bottom to assist you in scrolling to the area of interest.

Let’s just say that if the NIL had been legalized in the 1970s instead of in 2021, the SWC schools and administrators who suffered the consequences for rule infractions would be celebrated in collegiate sports circles for their foresight in buying the services of 18 to 22-year-old boys using a legal facade.

THE POWER OF MONEY in THE SWC was always king

Backstabbing, cheating, and open pocketbooks, starting in the 1970s and climaxing in the 1990s, destroyed the SWC. Other factors were also responsible for the demise of the SWC, including:

-

Arkansas’s joining the Southeastern Conference;

-

Private schools were no longer able to compete financially with state schools;

-

too many Division I teams in one state to support a solid fan base for all Texas Universities;

-

the SWC was too regional in scope for national exposure;

-

The Cotton Bowl’s contractual obligation to feature the SWC winner against another ranked team became an anchor around the Bowl committee’s neck. At best, the SWC teams’ play was mediocre.

Southwest Conference survived from (1914 to 1996, although its dissolution began in 1991 when the Arkansas Razorbacks left for the SEC). Texas won 25 conference championships.

Billy Dale says, “When I was a boy, I was young and impressionable, with dreams of wearing the Longhorn helmet and playing in the SWC. For many, it became a nightmare.

The Southwest Conference trophy room was full of burnt orange

Texas, from the inception of the SWC in 1915 until 1976, racked up many SWC trophies.

-

Out of 58 football titles, the Longhorns won outright or shared 20 of them;

-

Of the 60 SWC championships in baseball, Texas had 49;

-

15 of the 61 basketball titles;

-

30 of 50 golf championships ;

-

14 of 30 team titles in tennis;

-

won 36 track championships.

Dissolution

In the early years, the problem with the SWC was not talent; it was geography. Other than Arkansas, every school was in the state of Texas. Consequently, the SWC got very little national exposure. The weak sisters in the conference made the situation even worse.

Blake Brockermeyer’s story is symptomatic of the SWC’s poor reputation with high school athletes who were leaving the SWC to play for more exciting conferences.

Blake Brockermeyer -the Reluctant Longhorn.

Blake’s father, Kay, was an offensive lineman for Texas, but his son never intended to sign with Texas. Blake had other visions for his future in college football. UCLA, Florida State, Washington, and…… were his dream schools. As with many high school players in the late 1980s and 1990s, Blake was not impressed with the SWC. A conference composed of Texas schools and Arkansas. He says in the book “The Road to Texas” by Mike Roach, “You know, TCU wasn’t very good, and I didn’t want to stay at home anyway. Texas had not been very good the last few years, and so really, I thought if I wanted to get to play somewhere” else….. It took the influence of strength coach Dana LeDuc, Coach David McWilliams’s charisma, and his parents to convince him to play in the SWC.

Quotes from Blake Brockermeyer and B.J. Johnson are in this book by Mike Roach

B.J. Johnson “ I never grew up wanting to go to Texas.”

B.J. Johnson is another example of a Texas athlete who wanted to leave the state to attend a more exciting conference. B.J. says, “Texas was never a school I watched that often.” “Florida State was the school that I wanted to go to naturally.” “ I didn’t start loving Texas until I had to go down to a football camp.” When I met Darryl Drake, “That’s kind of what made me start liking Texas and having some interest.”

Johnson caught 71 passes that season for 1,749 yards and 20 touchdowns. In three seasons and 42 games as a starter, Johnson had 135 catches for 3,059 yards and 42 touchdowns. Johnson was heavily recruited and chose to attend Texas.

In 2000, Johnson was the first freshman to start at wide receiver since 1992 and then had one of the best freshman receiver seasons in school history setting seven records. He set the school’s freshman single-season record with 41 receptions and also set the school’s single-game freshman for receptions (9) and receiving yards (187) in 2000.

He caught the game-winning catch against Texas Tech in 2003.[4]

Even in the early years of the Big 12, many great high school players wanted to play out of the state. When Fozzy Whittaker was in middle school, he was a Miami Hurricanes fan. Fozzy says, “I loved the University of Miami…. especially in the 2000, 2001, and 2002 era.”

But when Ricky Williams had his Heisman run and Cedric Benson joined the Horns, he became more interested in Texas’s Longhorn Defensive line. Coach Oscar Giles first contacted Fozzy to express Texas’s interest in making him a Longhorn. Fozzy joined the Longhorn Nation in 2007. The 2007 class was ranked 3rd best in the Nation this year.

Roy Miller

Roy Miller’s road to Texas was a tough one. Like many high school athletes, the SWC and Big 12 were not on his radar screen in his early years. His favorite team was Mack Brown’s North Carolina team. , but when his dad moved to Killeen, TX., and he saw all the Longhorn support groups, it impressed him. His story of the recruiting trail, starting at 15 years of age with Baylor and Oklahoma until he signed with Texas in 2005, is one that should be read by all high school athletes and their parents.

Table of Contents

-

Article written by Madeline Coleman about the NIL.

-

NOVEMBER 16, 1992

“SORRY STATE- FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST CONFERENCE ISN’T WHAT IT USED TO BE, AND TEXAS AND TEXAS A&M ARE LOOKING TO BAILOUT”- BY SALLY JENKINS

-

All the King’s men could not put Humpty Dumpty together again. After 81 years, the outstanding offensive and defensive minds of the coaches and exceptional athletes who played in the SWC were finally destroyed by self-interest, politics, T.V. rights, greed, oil, and petty hearts. Distrust, win at all cost, and economic tensions led to changes in SWC recruiting protocols, resulting in many NCAA recruiting violations. Wealthy donors were more than happy to assist in recruiting high school athletes, but as businessmen, they demanded a return on investment known as winning.

-

The SWC and Infractions galore

-

On December 2, 1995, the lights to the SWC went dark

-

Why Arkansas left the SWC

-

Transition to the Big 12 format.

-

The history of the Texas vs. Arkansas series- (it is not what you think)

-

Frank Erwin

-

More reasons for the death by suicide of the SWC.

-

Royal, Akers, McWilliams, Mackovic, and Moffett.

-

The lONGHORN SWC history

#1 Madeline Coleman

MADELINE COLEMAN about the NIL For Sports Illustrated.

Nick Saban Says NIL Rules Creates System Where ‘You Can Buy Players.

The name, image, and likeness (NIL) era has altered college sports for good, and it is still split on whether the change is for the best.

Alabama coach Nick Saban shared his thoughts on the matter in a recent interview with the Associated Press, highlighting his concern about the state of the NCAA.

“I don’t think what we’re doing right now is a sustainable model,” Saban said. “The concept of name, image, and likeness was for players to use their name, image, and likeness to create opportunities for themselves. That’s what it was. So last year on our team, our guys probably made as much or more than anybody in the country.

“But that creates a situation where you can buy players. You can do it in recruiting. I mean, if that’s what we want college football to be, I don’t know. And you can also get players to use the transfer portal to see if they can get more somewhere else than they can get at your place.”

We now have an NFL model with no contracts, but everybody has free agency,” Saban added. It’s okay for players to get money. I’m all for that. I’m not against that. But there also has to be some responsibility on both ends, which you could call a contract to develop people in a way that will help them succeed.”

Prominent college football coaches have echoed similar sentiments, including Clemson’s Dabo Swinney, USC’s Lincoln Riley, and Ole Miss’s Lane Kiffin. Swinney has discussed the matter at length, saying the transfer portal created “chaos” and referred to it as “tampering galore.” Swinney also noted he believes the NIL era will bring a decline in graduation rates.

“Kids are being manipulated,” Swinney said in December. “Grass is greener and all that stuff as opposed to putting the work in and graduating. There are no consequences. So now you’ve got agents and NIL, tampering, and you have no consequences. …

Education is like the last thing now.

“We’re going to have a lot of young people who aren’t going to graduate. … There are many kids whose identity is wrapped up in football, and all this does is further that.”

Kiffin has also been an outspoken critic of NIL rules.

“We don’t have the funding resources as some schools with the NIL deals. It’s like dealing with salary caps. I joked I didn’t know if Texas A&M incurred a luxury tax with how much they paid for their signing class,” Kiffin said in February,

Paying a player to attend a school still violates NCAA rules, though Riley recently told reporters the NIL landscape has “completely changed” recruiting.

#2 Journalist Sally Jenkins

SORRY STATE

FOOTBALL IN THE SOUTHWEST CONFERENCE ISN’T WHAT IT USED TO BE, AND TEXAS AND TEXAS A&M ARE LOOKING TO BAILOUT

The cheating that ran through the Southwest Conference in the 1970s and early ’80s was masterminded by some of the richest and most powerful men in the state. The payoffs and recruiting scams began as an attempt to correct a disparity in the conference that dates way back to 1923. In May of that year, oil was discovered in a west-Texas grape field that belonged to the University of Texas system. The oil and natural gas royalties from that find were placed into an existing account called the Permanent University Fund. The fund is now worth more than $3.7 billion. The state legislature decreed that two-thirds of the annual interest go to the University of Texas, and one-third to its next of kin, Texas A&M. None of the other schools in the conference receive so much as a dime from the fund.

All that lucre created a glaring imbalance of resources among the Texas-based schools in the SWC, and that was gradually reflected on the football field. A&M and Texas either won or shared the league title 18 times from 1940 to ’70. By law, the oil riches belonged to the big two, but as the ’70s approached, Longhorn and Aggie rivals decided that they were loath to let them have all the football riches too. TCU and SMU had power in the ’30s and ’40s, and their alumni—many of them oilmen riding the petroleum boom—wanted their gridiron glory back.

In 1967 William Clements, a successful oilman and SMU trustee, who would twice be elected governor of Texas, became chairman of the board of governors of SMU. Clements and his fellow Dallas businessmen on the board didn’t like to lose to anybody—not if money could prevent it. From 1970 to ’86, SMU’s endowment jumped from $26.7 million to $282.1 million, and the Mustangs climbed to national football prominence, an ascension that culminated in a record of 41-5-1 from 1981 to ’84, thanks to players like Craig James and Eric Dickerson. It was during this era of football success that payoffs to Mustang athletes and recruits became a virulent disease.

Wealthy SMU alumni, not content with having ruined their own program, proceeded to spend their time and money trying to get the other SWC schools in trouble: A fund was reportedly devoted to investigating rivals and turning them in, and by the end of the ’80s, TCU, Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech and Houston—which hadn’t even joined the league until ’76—had all been punished to varying degrees by the NCAA. Only Arkansas, Baylor, and Rice emerged unscathed.

By the mid-1980s the conference was so tainted that homebred football talent, considered to be among the best in the country, began fleeing to other states, an exodus that has not stopped. In 1986 the state of Texas had 12 recruits ranked among the top 100 nationally, and seven of them left the state to play their college ball. Last year four of the top 10 chose to leave the state.

The Aggies and the Orangebloods get misty-eyed when they contemplate this sorry end to a storied alliance, but after decades of politicking and bickering, they have mainly themselves to blame.

But on the eve of 1993, oil prices are dismal; a woman, Ann Richards, is governor; the Longhorns have had losing records in three of the last four seasons; and the Southwest Conference, which hasn’t had a national champion since 1970, is on the verge of collapse under the weight of weak football and bad business practices.

Arkansas left for the SEC last year. The payoff scandals deplete the eight remaining teams of the 1980s. Texas and Texas A&M, the wealthy standard-bearers of the conference, would love to bolt, except that they would face bruising resistance on the state legislature floor and the potential loss of millions of dollars in state funds if they tried it.

You can’t discuss the rise and fall of football in Texas without discussing the state’s business and politics, and specifically the business and politics of its most venerable institution, the University of Texas. Longhorn football has long been a training ground for the state’s leaders. James R. (Jim Bob) Moffett, for instance, a poor kid and a rather ordinary player under Royal in the 1960s, is now the school’s most influential alumnus. “As the state university’s football team goes, so goes the state and the favorite sons of the state,” he says.

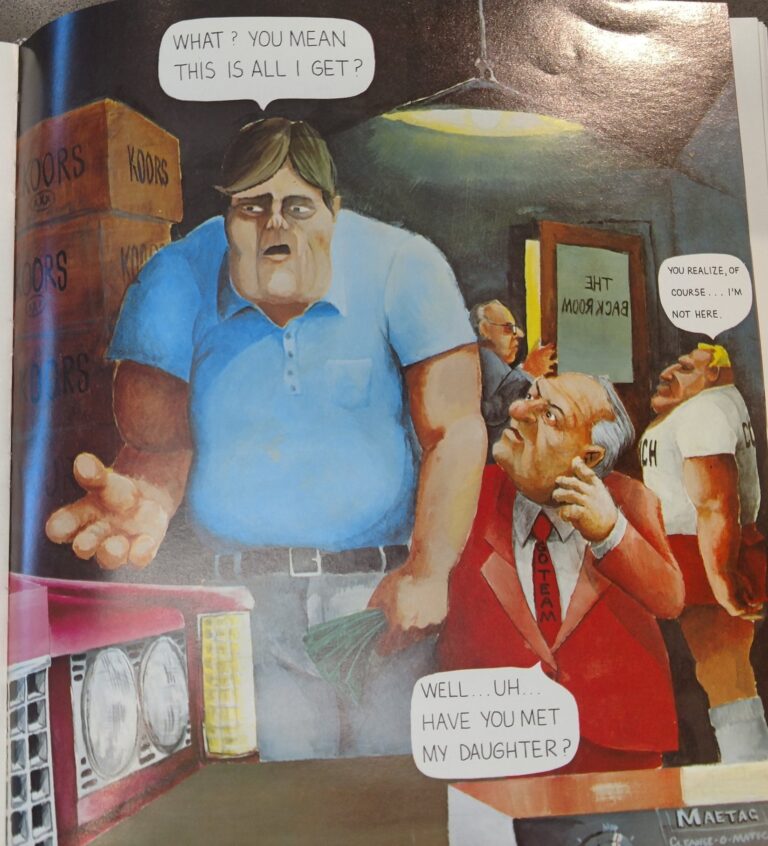

As Royal’s teams won national championships in 1963, ’69, and ’70, politics and football in the state became ever more entwined. They twined together most tightly at Cisco’s, a back-room joint that has been the favorite breakfasting and deal-making spot in Austin, the site of both the state’s capital and its main university, for 42 years. On any given morning, you can still see the vestiges of the old days. In one corner sits George Christian, a former LBJ aide. In another is Mike Campbell, a former assistant coach under Royal and the man Royal wanted to be his successor. Royal used to have breakfast at Cisco’s most Sunday mornings. It was there that the power brokers of Texas met to get the work of the state done—and that surely included football. The proprietor of Cisco’s, Rudy Cisneros, says, “I’ve seen more big deals than you can imagine going down in this room right here.”

The two links below are the unedited full stories of the demise of the SWC, as told by ESPN and the Texas Almanac.

https://texasalmanac.com/topics/sports/look-back-southwest-conference

#3 AND ALL THE SWC MEN

Round Robin’s SWC play started in 1934, and through 1959, it only won all the games in the conference seven times.

After 81 years, the outstanding offensive and defensive minds of the coaches and exceptional athletes who played in the SWC were finally destroyed by self-interest, politics, T.V. rights, greed, oil, and petty hearts. Distrust, win at all cost, and economic tensions led to changes in SWC recruiting protocols, resulting in many NCAA recruiting violations. Wealthy donors were more than happy to assist in recruiting high school athletes, but as businessmen, they demanded a return on investment known as winning.

SMU was the worst polluter of the NCAA recruiting guidelines. When SMU started beating Texas and A&M consistently, red flags increased throughout the SWC. Why and how was SMU able to compile a 45-5 record? For everyone not blinded by money, the answer was obvious. With a bit of squealing to the NCAA from member SWC Universities, the question was finally answered. SMU was filling their coffers with death penalty amounts of cash from the donor class to purchase players. SMU got caught, but the University and their Coach, Ron Meyer, struck back at those who reported SMU to the NCAA—accusing other SWC teams of recruiting irregularities. The NCAA listened, and except for Baylor and Rice, all SWC teams received some form of punishment for breaking NCAA rules. The win-at-all-cost mantra led the SWC off the cliff. Public opinion of the SWC ethics reached new lows, losing the state of Texas high school recruits to the Southeast and beyond.

Mike Glazier, NCAA enforcement 1979-86, said, “There was a lot of money/benefits provided to athletes to attend certain schools. SMU got caught up in that then, and other schools tried to compete with SMU, Texas, and Texas A&M. Mike says, “Who knows? It’s a chicken-and-egg deal. But then, I think many would have considered football recruiting in the Southwest Conference to be — I don’t know what the right term is … but almost [with] no limits.”

The boys who played against each other in high school did the same when they joined the SWC. Even the coaches were intertwined. Spike Dykes coached at Texas and Texas Tech and for Emory Bellard at San Angelo Central. Emory worked for Darrell and took his wishbone creation to Texas A&M. It was not unusual for the competing coaches on Friday night to have dinner together before the game on Saturday.

#4 The SWC -Infractions galore

Many people believe that there were two reasons for the demise of the Southwest Conference. They were starting with ESPN’s entry into the sports cable market. ESPN offered teams a long-term marriage with national exposure. However, no money was involved for a while, and the Southwest Conference rejected ESPN’s offer, saying it wanted money upfront. Others felt that recruiting infractions in the 1980s were the evil culprit leading to death by suicide of the SWC. SMU, TCU, Texas A and M, and Houston all experienced NCAA probation for recruiting excesses.

The Southwest conference leaders felt like they were being picked on, referring to two Florida and Miami infractions that started each game with a burglar alarm going off. But the fact is, the SWC teams got caught because they were sloppy in illegal recruiting and were stupid enough to confess to the infractions.

The Texas teams’ immense state pride and egos played against the conference. Everyone wanted to be the king of football in Texas, and in the 1980s, a war raged to claim the crown.

In 1985, the NCAA banned SMU from bowl games for two seasons and stripped the Mustangs of 45 scholarships over two years. It was one of the strongest punishments in NCAA history. It stemmed from a payroll system for players involving wealthy boosters. The same year, oilman Dick Lowe, a TCU trustee, confessed to helping the Horned Frogs with their slush fund and personally paying players, including star running back Kenneth Davis. The scheme “was born out of total frustration, from getting our butts beat by people we knew were buying players,” Lowe told The New York Times. “I think there are 91 Division 1-A schools, and my assessment is that 80 are buying football players.” The SWC could not keep its members from pointing fingers at each other at the NCAA.

In 1987, the NCAA gave SMU the “death penalty. It was the first and only college football program to receive this punishment.

Nothing scarred the league more than the NCAA’s “death penalty” handed down to SMU in 1987 after being designated a repeat offender for continuing the payroll to honor its promise to some players. The Mustangs were forced to cancel their 1987 and ’88 seasons. After going 41-5 in the pre-probation years from 1981 to ’84, the Mustangs had only one winning season from 1989 to 2005 and would not win ten games again until 2019.

SMU’s 41-5 record success was built with NCAA flagrant infractions. Once illegal recruiting began, there was no going back, and teams’ cheating forced other members of the SWC to report violations to the NCAA, which angered alumni, who then spent money to go after other schools. Hard feelings pervaded the SWC. Recruiters went to church on Sunday and prayed that they gave recruits enough inducement to attend their fine university.

The SWC earned the tagline “Sure we’re cheating.” SWC had become a distorted mosaic of petty hearts with suicidal conference-destroying tendencies.

Aggie coach Slocum said, “It was so competitive within the state that some people got out of bounds. Once they started, well … “He’s doing it too!”

Slocum: We were our own worst enemies. Everyone in there hated everybody. There never was a “what can we do collectively to uphold our league?” I never saw that. At meetings, it was, “Hooray for me!” and “Screw you.”

Grant Teaff, Baylor coach, 1972-92: Some of us weren’t cheating and were not going to cheat. And so it’s hard to go out on a football field and know that you can have that player and he could be scoring touchdowns for you, except that black bag arrived at the little airport. Everybody knew everything that was going on. You knew when the new cars were delivered. You would get a call from someone in that town: “So-and-so got a new car today.”

What destroyed SMU in the SWC eventually hurt the image of all the teams in the conference. The SMU death penalty was the beginning of the end for the SWC. The conference was tainted in the eyes of High school recruits and their parents, so Texas athletes started leaving the state in droves, headed primarily East toward Miami.

The book “Sports Revolution” by Frank Guridy says that the most crucial reason the SWC disappeared is that sports media money drove the decision-making process of conference opponents. Frank Guridy says:

“ The historic breakup of the NCAA’s regulatory power over television rights of member schools television contracts in 1984 sent universities scrambling to find as much television money as possible. This situation was further complicated by the proliferation proliferation of cable television networks spearheaded by the ascendance of ESPN which accelerated the scrambling for television money. Over the next few decades conferences and individual schools develop their own television networks. “ Choosing to “Maximize television revenues not rivalries or geographic proximity became a primary justification in the organization of athletic conferences.”

While the conference finally tempered its recruiting excess, the old grudges never died. The financial divide between the big state and private schools continued to grow, infighting continued and the conference started to show cracks in the foundation.

#5 December 2, 1995, the lights to the SWC go dark

On December 2, 1995 David Barron wrote the article below.

Dick and Margie Hudson turned out the Rice stadium lights to end the SWC. The league that began in 1915 with a Rice game ended with a Rice game.

The final game of the SWC was indicative of one of the many reasons the Conference died— lack of attendance from the private school in the SWC. Rice and Houston played a game before 25,000 paying customers. Rice was so determined to have an excellent ending to a lousy conference that the administration decided to open the gates and let people in at half-time. Five thousand more people showed up, many wearing the colors of the other 6 SWC schools. Baylor, Tech, Texas, and A&M fans dominated the color spectrum.

The fans saw an exciting game won by Houston with 1:19 seconds to go.

The SWC exited the stage after winning seven national championships (SMU, 1935; TCU, 1938; Texas A&M, 1939; Arkansas, 1964; and Texas, 1963, 1969, and 1970). he SWC also produced 5 Heisman Trophies- TCU’s Davey O’Brien, 1938; SMU’s Doak Walker, 1948; A&M’s John David Crow, 1957; Texas’ Earl Campbell, 1977; and Houston’s Andre Ware, 1989. The league also produced five winners of the Outland Trophy- Arkansas’ Bud Brooks, 1954; Texas’ Scott Appleton, 1963; Texas’ Tommy Nobis, 1965; Arkansas’ Loyd Phillips, 1966; and Texas’ Brad Shearer, 1977.

The SWC alone boasted over 350 first-team all-America athletes in football, basketball, and baseball. The State of Texas track-and-field stars included three historic Olympians. Baylor’s Michael Johnson scored the rarest of doubles in 1996, winning both the 200 and 400 at the Atlanta Games to cap a career-best year in which he set world records in both races. In 1984, Houston’s Carl Lewis became the first Olympian to win four gold medals in one Game since Jesse Owens in 1936 and added five more golds in the 1988, 1992, and 1996 Olympics. exas A&M shot putter Randy Matson, the first ever to throw past 70 feet, won the gold in 1968 and held the world record longer than anyone in history. In the fall of 1996, the final eight SWC members scattered to their new conferences.

Then-Houston coach Kim Helton summed up his feelings about the two gorillas in the SWC -Texas and A&M- in the Houston Chronicle, saying, “We do recruit against Texas A&M and Texas, and I’m glad they’re somewhere else playing against each other.” I’m glad they are going to other conferences. I don’t care what happens to them. I don’t wish either of them well.”

Kim’s comments were not justified. The comments of two great universities are tinged with jealousy, contempt, and envy. Kim should have directed his venom at many other reasons that destroyed the SWC- not two universities.

#6 Why Arkansas left the SWC

While the feuds, scandals, NCAA rules infractions and fan apathy were indeed reasons for the death of the Conference, the official beginning of the end can be traced to a 1984 Supreme Court case in which Oklahoma and Georgia won an antitrust case against the NCAA, seizing control of television deals. Market size and TV sets were significant factors in conference affiliation. Ith the SWC is so saturated, with 90% of its schools in one state, that it hurt its marketability for a big-money TV deal. It was a regional conference in a sport going national.

Arkansas was the first to see the need to leave the SWC to maximize revenue for the Arkansas program. The SWC paid visiting teams $175,000 per game, which Arkansas said was unfair. Arkansas fans followed the Razorbacks to Rice, SMU, TCU, and…. and helped fill their stadiums but only received $175,000. When Rice came to Arkansas, the Owls brought 400 fans, but the institution still received $175,000.

Sherrill says: “I remember sitting in the meeting when Arkansas was going to the Orange Bowl to play Oklahoma, and they asked for half a million dollars more in part of the pot for traveling expenses and other things, and you had TCU, SMU, and Rice, who were not willing to give them the extra expense money. I raised my hand and said, “Hey, if one team goes to the Orange Bowl or any other big bowl like that, that brings prestige to the whole conference.” Reluctantly, the [schools] passed [the request], but there were votes against.”

Toward the end, attendance had become a significant problem for the league’s smaller schools, with Texas, Texas A&M, and Arkansas subsidizing the rest of the conference teams.

Coach Broyles said, “There was no magic formula to turn the tide back to Rice and SMU being the kingpins in attendance like they were in the old days.” Houston and Dallas were no longer college football cities. They were pro football cities, relegating SMU, TCU, Rice, and the University of Houston to small fan bases. Broyles said, “There was no way to turn the clock back. How do you regain pride in a conference with probations and a lack of attendance?”

SMU moved back to Ownby Stadium, which held just 23,783. Texas A&M drew seven of the ten biggest crowds in the history of Baylor’s Floyd Casey Stadium. Ice Stadium, which had 70,000 fans and once hosted a Super Bowl, drew a 5 A high school attendance of 17,900 for a 1990 game against SMU.

In November 1990, 25,725 fans showed up at the Astrodome to see No. 6 Houston (8-0) play 5-2 TCU, a game in which TCU’s Matt Vogler set FBS records with 79 pass attempts for 690 yards, and Houston’s David Klingler threw for 563 yards and seven TDs. The 1,563 yards of total offense was another record only since surpassed by Texas Tech and Oklahoma’s 66-59 shootout between Patrick Mahomes and Baker Mayfield in 2016.

On July 13, 1990, Arkansas athletic director Frank Broyles, the legendary former coach of the Razorbacks, told reporters at an SWC meeting that he was going to meet with SEC reps the next week to consider a move, but that it was a “strong possibility” they would stay if changes were made to their liking.

On July 30, 1990, Broyles and Arkansas announced the school was officially accepting the SEC’s invitation, becoming the first in the modern era to jump from one major conference to another, ushering in the new world of realignment.

On Aug. 4, 1990, Crowe was dispatched, along with quarterback Quinn Grovey, to the Southwest Conference kickoff luncheon in Dallas, the conference’s media day. He said he was booed for three minutes straight

After Arkansas gave their notice Coach Teaff said “if we had any common sense, we knew that it was probably the beginning of the end” for the SWC. The SEC administrators knew instinctively that private or church schools fan base would not convert to dollars with a T.V. audience so the SEC chose primarily state schools.

Barry Switzer agreed saying, “there were too damn many Little Sisters of the Poor. Private schools, church schools, and small schools.” Rice vs TCU would not excite a national football audience. Coach Switzer who played for Arkansas said that Coach Broyles said “Hell, as soon as I signed the contract, I got a $6 million raise for our program.”

The SWC would soon learn that the formula for monetary success was quite simple. Money was a function of the number of T.V. sets, great state rivalries, viewers, and full stadiums. Four private colleges in the SWC did not possess any necessary formula elements to make significant money from T.V. appearances. The contest between private schools and church schools in the SWC did not fit the T.V. formula for making money.

#7 transition to the Big 12 format.

The Supreme Ruling changed the Landscape of college football and exposed the weakness of private schools and church schools’ ability to fill stadiums and excite T.V. viewers.

What T.V. sports viewers wanted to watch were now the kingmakers.

Let’s Make a Deal for T.V. rights begins with Notre Dame signing a contract with CBS. That deal exposed the motives of academic institutions. Joe Paterno said, “We got to see Notre Dame go from an academic institution to a banking institution.” The race for the best T.V. contracts was on.

Penn State moved to the Big 10 for “economic” reasons, and Arkansas was invited to join the SEC. For some reason, the members of the SWC still did not understand that money was one of the primary driving forces of Arkansas’s decision, not disloyalty. The SWC official’s comments were clueless and knee-jerk, saying “the Iraq of college football “is the SEC.

As the Big 12 merger neared, Texas politics played a key role in who was invited.

As the money formula took hold of the SWC, Texas pursued several options. U.T. considered the Pac 10. It would include exciting road trips playing prestigious universities on the West Coast. On the other hand, joining the Pac 10 would hurt viewing in the central and Eastern time zone. Jumping to the SEC was the logical money choice maximizing state rivalries and T.V. viewers. Texas and Texas A & M would have probably jumped to the SEC, but Texas state politics got involved, and the two universities “decided” to remain in the SWC.

Public schools get public funding and it just seemed like the legislature would want to make sure it happened. Then out of the blue, Houston was out and Baylor was in.

Texas governor at the time, Ann Richards, was a Baylor graduate. Lt. Gov. Bob Bullock graduated from both Texas Tech and Baylor. The Texas House Speaker [Pete Laney], House Appropriations Committee Chairman [Rob Junell], and Texas Senate Finance Committee Chairman [John Montford] were all Texas Tech graduates.

According to the book “Bob Bullock: God Bless Texas,” by Dave McNeely and Jim Henderson, Bullock summoned Texas and Texas A&M’s presidents to his office in early 1994 as the merger neared. “You’re taking Tech and Baylor, or you’re not taking anything,” Bullock told them. “I’ll cut your money off, and you can join privately if you want, but you won’t get another nickel of state money.”

The Big Eight officially invited Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech, and Baylor in February 1994. Those at Houston, Rice, SMU, and TCU were stunned.

The SWC egos didn’t change much in the new Big 12. Teams were wary of Texas’ influence and aspirations, and nobody could agree on much at first. The Big Eight teams considered the new structure as an expansion. The SWC schools viewed it as a brand-new conference. The first proposed logo was the same as the old Big Eight’s, but the number was just changed to a 12. Even that irked the SWC teams.

#8 The history of the Texas vs. Arkansas series- (it is not what you think)

Arkansas and Texas had some great games in the series, but as a competitor to Texas, the record reflects no rivalry. In fact, Rice beat Texas more times than Arkansas did . Texas’s record is 52 wins and 18 losses against Arkansas. Perhaps that is the reason Arkansas fans hate Texas more than Texas fans hate Arkansas.

Arkansas fans say the losses accumulated due to either better Texas teams or Arkansas finding a way to lose. Arkansas coach Broyles knows why. In football, psychology is just as crucial in winning as schemes and strategies, and psychologically Texas had Arkansas number.

An Arkansas head coach in 1989 said that the week before the Texas game, the Razorback’s personality changed, resulting in the team playing tentatively against Texas. The coach said, “It was like we were walking in sand.

#9 Frank Erwin

Back then, most of the big deals were done by a man named Frank Erwin, an intimate of LBJ’s and Connally’s. “Frank Erwin drove an orange-and-white Cadillac with longhorns on the hood, and when he honked, it played The Eyes of Texas,” says Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist Molly Ivins. “Does that explain him?”

Erwin was a member of the Texas Board of Regents, which oversees the state university’s eight campuses, from 1962 to ’75 and was chairman for five of those years. Erwin exercised control over all aspects of the University of Texas at Austin’s affairs. In 1968 he pushed through a $15 million plan to expand Belmont Hall, the complex of athletic offices built into the side of Memorial Stadium. But a group of students and activists objected because the plans called for razing a row of beautiful old trees. While protesters clung to the branches, awaiting a judge’s order that would have stayed the tree-cutting, Erwin personally directed construction workers to topple the trees with chainsaws. The judge’s order arrived 45 minutes after the job was done.

Erwin was at once a tyrant and a charmer, but he never charmed Royal. Erwin sought to influence Texas football as he had over the rest of the university’s affairs, but for nearly 20 years, Royal resisted him. Then, in 1976. Royal decided to retire.

According to some, Royal got out because a few highly placed state officials and alumni had observed the rampant cheating in the conference and intimated that he should join in. Royal, a man who won’t even improve a golf lie, refused. When he declared that he wanted Campbell to succeed him, Royal found himself in a power struggle with Erwin and Allen Shivers, a former governor who had become a member of the board of regents. Shivers didn’t like Royal’s affection for longhaired musicians like Willie Nelson, and he didn’t like Campbell; he liked the fresh-faced Fred Akers, who had also been an assistant under Royal and was doing well as the coach at Wyoming.

Royal may have been the most popular man in the state, but he wasn’t the most powerful, as he discovered. Akers got the job. Royal continued as athletic director at Texas for three more years after he stepped down as coach, but Akers, Erwin, and Shivers made it known that they didn’t like having him around. Finally, in 1979, Royal decided to remove himself from the athletic department altogether. As Royal walked down Belmont Hall’s steps on the day he resigned as athletic director, he passed another department official. “I’ll be back,” he promised.

#10- More reasons for the death by suicide of the SWC with Sally Jenkins

Texas and Texas A&M are observing their struggling brethren and concluding, Who needs them? The big two dominate the state’s T.V. markets and, thus assured of their own survival, show little inclination to financially assist the league they helped to found in 1915. “It’s a bunch of institutions that care more about themselves than each other,” says former Texas women’s athletic director Donna Lo-piano, who left the school in March to head the Women’s Sports Foundation. “It’s a bad business conference.”

Proof of that is that Texas and Texas A&M won major concessions from the rest of the league, which further weaken the smaller schools. Gate receipts used to be divided 50-50 between the home and visiting teams, but beginning this season, the home team retains all gate receipts. That’s a bonanza for Texas and Texas A&M, which draw the biggest crowds. Bowl participants—read the Longhorns and the Aggies—will keep the first $500,000 they earn for postseason appearances, instead of the first $300,000. (In the Southwest Conference, the leftovers are divided among the have-nots, but in the Big Ten, all schools share equally in a bowl gate and T.V. receipts.) And as of this year, SWC schools playing in televised nonconference games keep 80% of the T.V. money instead of splitting the fees 50-50 with the rest of the league, as had been the case.

Is this any way to save a conference? That is not a priority at the University of Texas. “The reality is, U.T. has to finance its own agenda,” says Mullen. “The university has to look at how to draw the biggest revenues.”

And that means it no longer makes any sense for big schools like Texas and Texas A&M to play ball—as business partners—with the likes of Rice, SMU, and TCU. It is widely believed that the Longhorns and the Aggies, if not actually orchestrating the demise of the Southwest Conference, are doing nothing to relieve the crisis, hoping that the conference will dissolve, leaving them free to join a league in which the schools are bigger, and the little guys will not drag them down.

However, Texas and Texas A&M cannot make the first move to break from the league for one powerful reason: money. The legislature could vote to cut off state money to the big two if they bolt. “The SWC is viewed as an economic asset of the state,” Lopiano says. “To leave the SWC could be seen as detrimental to the state.”

In 1990, fearing that Arkansas’s departure for the SEC would spur the Longhorns and the Aggies to follow suit, the legislature’s state affairs committee considered calling a special hearing on Texas football. At the time, Speaker of the House Gib Lewis, a TCU alumnus, said, “If they want to leave the Southwest Conference, we can cut their funds with one vote. One simple vote.”

Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock, a Texas Tech graduate, added, “Those who consider moving ought to take a course called Common Sense 101. They’d be making a big mistake with the decision-makers of Texas.”

Sentiments have not changed. State Senator David Sibley of Waco, a Baylor grad (as is Governor Richards), says, “If A&M and Texas want to leave the SWC, the next time they want to talk about appropriations for new physics professors, they’d have to come through me.”

Texas athletic director DeLoss Dodds says only that the long-range future of college football is the superconference—perhaps 40 of the biggest, wealthiest schools forming a handful of alliances, with the rest dropping down or dropping the sport. “The world is going to dictate where Texas goes,” he says. “The marketplace will dictate it.”

Indeed, the Southwest Conference’s council of presidents believes that the Big Ten and the Pac-10 will follow the SEC in expanding to 12 teams, and a growing sense of urgency about losing Texas and Texas A&M prompted the presidents to vote last Thursday to approach the Big Eight, which is worried about losing Colorado to the Pac-10, about a merger. The lure of such an alliance is the money that would be earned from a playoff game between the champions of the two divisions of a conference—the members of the SEC will divvy up $6 million from the league’s first playoff, on Dec. 5 in Birmingham—and from TV-rights fees. After all, 16% of the T.V. sets in the country are located in the Big Eight and Southwest Conference regions.

An association with the marquee schools of the Big Light—Nebraska. Oklahoma and Colorado—would add luster to the Southwest Conference, and the Big Eight would enjoy the profits and the exposure generated in the big Dallas and Houston TV markets. Above all, a strong alliance could survive if some of its members decided to drop football, de-emphasize it or move to another league.

If the Southwest Conference does unravel, it will most likely do so from the bottom. At Rice, the debate over whether the university can afford to continue playing Division I-A football was a factor in the abrupt resignation last month of President George Rupp. Rupp was said to have grown weary of trying to mediate the endless tug-of-war between a board of trustees wedded to big-time football and a faculty that recently voted to toughen academic standards for the school’s athletes, even if that meant having to drop out of the Southwest Conference.

In 1987 SMU brought in a new president, Kenneth Pye, from Duke, to try to restore credibility to the school after the scandals. Now he, too, is under intense pressure from football-feverish alumni for raising academic standards and commissioning a task force to study a projected $4.9 million athletic-department deficit. The task force’s report, which is due next month, will most likely determine whether SMU stays in Division I-A, drops down to Division II or even III, or gives up football. The battle lines have been drawn. “We are not Harvard,” declares Craig James, now a commentator with ESPN. “Let’s get off this high throne, and all the academics can go work at Harvard.”

When Erwin died in 1980, his funeral was held in Austin’s campus arena that now bears his name. As the pallbearers carried in his coffin, all 2,000 mourners rose, singing The Eyes of Texas. No one since has had the kind of power that Erwin wielded.

#11 Royal, Akers, McWilliams, Mackovic, and Moffett.

Akers, Erwin’s handpicked coach, had two 11-1 seasons, in 1977 and ’83, and a Heisman Trophy winner in Earl Campbell in ’77, but he never won hearts, which remained firmly in Royal’s possession. In ’86, when Akers presided over Texas’s first losing season since ’56, there was no one to save him. He was fired, then replaced by a favorite son of Royal’s, David McWilliams, a defensive tackle on the 1963 national-championship team who wore jeans and boots and said ma’am.

McWilliams was Royal’s choice, but he was also the wrong choice. He was not a strong leader, nor could he recruit outside Texas. And while the Longhorns were suffering three losing seasons in five years, their graduation rate fell to 27%. Last January, McWilliams resigned.

Now, there is a new power base at Texas, and out front is Royal, the man who promised he would be back. But behind him is Moffett, 53, his former player who went on to become a fabulously successful wildcatter. Moffett’s New Orleans-based company, Freeport MacMoRan, is worth $1.7 billion. When it became clear midway through the 1991 season that McWilliams would have to go, Texas convened a committee to search for a new coach. A 50-member panel spent an entire day drafting a list of qualifications. But that was just for show. When John Mackovic, who had been in Illinois since ’88, was selected, only four men were really involved in the decision: Moffett, Royal, Dodds, and university president William Cunningham, who has since become chancellor of the Texas system. But the power lay with Moffett because says one source close to the athletic department, “Jim Bob runs Cunningham.” Mackovic was chosen because he possessed Moffett’s characteristic: a sound of cold business sense. That attitude is guiding the Longhorns in the ’90s.

Royal likes to size people up based on whether they would be good company on Willie Nelson’s tour bus. For instance, Texas basketball coach Tom Penders will hang out on the bus and drink a couple of beers with you. Of Mackovic, Royal told Penders, “He’s not bus material.” But that doesn’t matter anymore, and it didn’t keep Royal from endorsing Mackovic wholeheartedly.

Mackovic has done the seemingly impossible in his first season at Texas. He has broken with tradition without mortally offending anybody. He junked the time-honored Longhorn running attack in favor of a pro-style passing game. As Mackovic embraces the future, he also courts the past. He had Royal address the team before its Oct. 10 game with Oklahoma, a resounding 34-24 win.

Three Longhorn freshmen further embody Texas’s attempts to blend tradition with the imperatives of the future: Shea Morenz, the top-rated quarterback in the nation as a Texas schoolboy, and a pair of wide receivers, Lovell Pinkney and Mike Adams. None of the three would have considered visiting Austin a year ago, much less sign with the Longhorns. Adams, a home-stater like Morenz, was the highest-rated receiver in the region but expected to go elsewhere to find a passing offense. Pinkney, a one-time crack dealer from Washington, D.C., reformed himself and became a high school All-America—and another key Longhorn acquisition. His presence demonstrates that Texas is finally able to attract talent from well outside the state.

About the only familiar ingredient in the offense is quarterback Peter Gardere, a senior from Houston. Bitter fans hold Gardere responsible for the losing seasons, despite having engineered four straight victories over Oklahoma, an unprecedented feat for a quarterback on either side of that rivalry. He holds eight school career passing records, but his parents have been hounded so badly that they changed their phone number. Gardere is booed even as he breaks the records of the revered Bobby Layne.

Sometimes, success isn’t enough if the Orangebloods decide they don’t like you. Akers found that out. So has Gardere. So, perhaps, will Mackovic. On the other hand, he could be at the helm when tradition is scattered to the winds, and the Longhorns join forces with their mortal enemy, Oklahoma, in a new confederation or forsake the Southwest Conference altogether for the Pac-10 or the Big Ten.

Gardere’s only regret is that he has to graduate, whereupon he will join the legions of favorite sons and passionate alumni. He is a handsome and self-assured kid from a wealthy family, a kid whose father and grandfather both played football for the Longhorns. He understands Texas football the way some overbred children instinctively know which silverware to use. “Texas football is big business,” he says. “And where there’s business in Texas, there’s politics.”

When Texas A&M left for the Southeastern Conference (Colorado, Missouri, and Nebraska also left of their own accord to the Pac-10, SEC, and Big 10, respectively). If any two schools have ever had a stronger love-hate relationship than U.T. and A&M, go ahead and name them. The Horns and Aggies would stay together, regardless of conference affiliation. So I assumed, and then the unthinkable happened. For reasons of their own—and one possibility is that they wanted to declare their independence from U.T.—the Ags departed. Although I could never have spent my student days in College Station, I respect and admire the Aggies. On Thanksgiving Day in even-numbered years, I used to go to Congress Avenue and watch them march up to the Capitol and then on to the stadium. It was a majestic scene.

No Need To Get All Teary-Eyed

The world is in flux; I know that. Some things that once seemed carved in stone have been tossed aside. We can adjust, or we can perish, or at least become irrelevant. I have no idea who is favored to win the Big 12 football championship this year, although it’s unlikely to be the Longhorns, who have been in an extended swoon. As for hoops, I am completely uninformed. Living abroad has afforded me a perspective I sure did not have back in the States. Even so, please cut me a little slack if I get wistful about the old Southwest Conference.

#12 The University of Texas SWC HISTORY national championships

The SWC started in 1914, and Texas set the tone in baseball, basketball, track and field, and tennis. The final SWC championship gave the Longhorns 375 conference crowns. The women claimed 85 of 112 conference titles. The men won 290 titles, and A&M was second with 84 SWC championships. In the final year of the SWC, the Horns – 1995-1996—claimed 11 of the 18 SWC titles.

Baseball – 1949, 1950, 1975, 1983

Men’s Golf – 1971, 1972

Men’s Swimming – 1981, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1996

Football – 1963 (AP), 1969 (AP), 1970 (UPI)

Women’s Swimming – 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1990, 1991

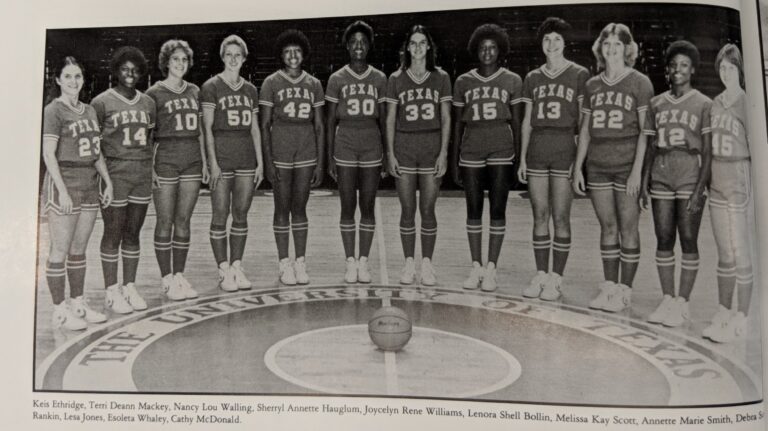

Women’s Basketball – 1986

Volleyball – 1981 (AIAW), 1988

Women’s Cross Country – 1986

Women’s Outdoor Track & Field – 1986

Women’s Indoor Track – 1986, 1988, 1990

Women’s Tennis – 1993, 1995

Below is a link to an article written by Texas Almanac sharing the history of the SWC.

https://www.texasalmanac.com/articles/a-look-back-at-the-southwest-conference