Dr. Don Thomas Nobel Prize

Dr. Don Thomas says, “my high school class consisted of about 15 people. I was not an outstanding student, even in this small group. I entered the University of Texas in Austin in 1937. In my first semester, I made only B grades, but as time went on and the courses became more difficult and challenging, I began to enjoy the studies, mainly in chemistry and chemical engineering. I received a B. A. in 1941 and an M. A. in 1943.”

The article about Don Thomas is in the link denoted in red-listed below.

The formation of blood cells takes place in bone marrow, and malfunctioning of bone marrow cells can lead to illnesses such as leukemia. From the mid-1950s Donnall Thomas developed methods of providing new bone marrow cells for people through transplants. Using radiation and chemotherapy, the body’s own bone marrow cells are killed and the immune system’s rejection mechanism is subdued. Bone marrow cells from a donor are then provided through a blood transfusion. Please see the video below.

SEATTLE – Oct. 20, 2012 – E. Donnall Thomas, M.D., who won the 1990 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for his pioneering work in bone-marrow transplantation to cure leukemias and other blood cancers, died today. He was 92.

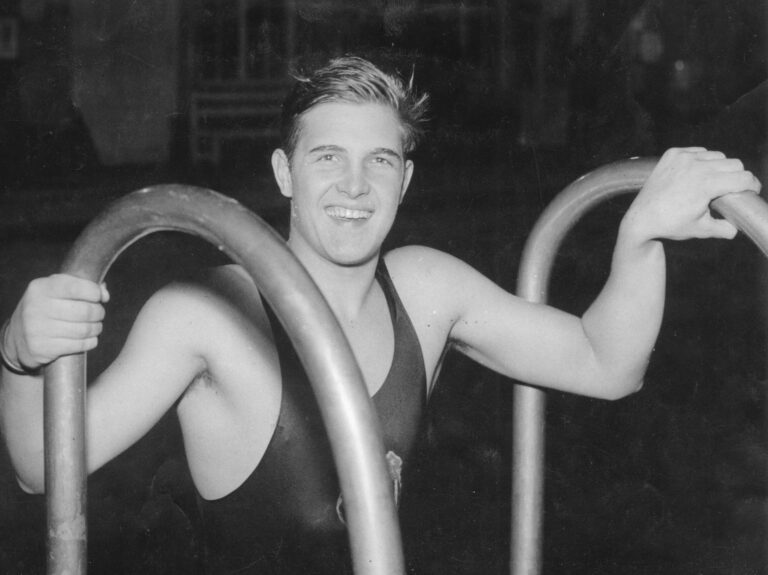

Dr. E. Donnall Thomas

Thomas joined the faculty of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in 1974 as its first director of medical oncology. He later became associate director and eventually director of the Center’s Clinical Research Division.

Thomas, along with his wife and research partner, Dottie – a trained medical technologist – and a small team of fellow researchers stubbornly pursued transplantation throughout the 1960s and 1970s despite doubts by many prominent physicians of the day.

“To the world, Don Thomas will forever be known as the father of bone marrow transplantation, but to his colleagues, at Fred Hutch he will be remembered as a friend, colleague, mentor, and pioneer,” said Larry Corey, M.D., president, and director of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. “The work Don Thomas did to establish marrow transplantation as a successful treatment for leukemia and other otherwise fatal diseases of the blood is responsible for saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of people around the globe.”

His groundbreaking work is among the greatest success stories in cancer treatment. Bone marrow transplantation and its sister therapy, blood stem cell transplantation, have had a worldwide impact, boosting survival rates from nearly zero to up to 90 percent for some blood cancers. This year, approximately 60,000 transplants will be performed worldwide.

Thomas edited the first two editions of the seminal bone marrow transplantation reference book, “Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation,” in 1994 and 1999, which became recognized as the “bible in the field.” He also contributed a chapter to the third edition, published in 2004, at which time the book’s title was changed to “Thomas’ Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation.”

“Don was a hero. He was, by far, the most influential person in my career, and I know that many others would say the same thing.”

Thomas was a member of 15 medical societies, including the National Academy of Sciences. He also received more than 35 major honors and awards, including the Gairdner Foundation International Award and the Presidential Medal of Science. He was past president of the American Society of Hematology and served on the editorial boards of eight medical journals.

Thomas came to Seattle in 1963 to be the first head of the Division of Oncology at the University of Washington School of Medicine. Continuing work begun in Cooperstown, N.Y., Thomas led a small team that labored in the basement of temporary facilities at the former U.S. Public Health Hospital. They sought to do what others were convinced would never work: to cure leukemia and other cancers of the blood by destroying a patient’s diseased bone marrow with near-lethal doses of radiation and chemotherapy and then rescuing the patient by transplanting healthy marrow. The goal was to establish a fully functioning and cancer-free blood and immune system.

It took almost 20 years after Thomas’s seminal paper on bone-marrow transplantation was published in The New England Journal of Medicine in September 1957 for the procedure to become an accepted therapy. During that time most medical professionals dismissed the idea.

“In the 1960s in particular and even into the 1970s, there were very responsible physicians who said this would never work,” Thomas said. “Some suggested it shouldn’t go on as an experimental thing.”

The early success was enough to convince Seattle surgeon William Hutchinson, M.D., to support Thomas and his team and build the group a permanent home. In 1972, ground broke for the construction of the original Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center building in Seattle’s First Hill neighborhood, and its doors opened in 1975.

Thomas and his team persisted because they believed transplantation was the key to saving the lives of people with leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and other fatal blood diseases.

“I’ve said in the past that I have two attributes: one is I’m stubborn to keep doing it and other is I attracted some good people to work with me,” Thomas told an interviewer in 2006.

Today, bone marrow transplants are a proven success for treating leukemia and other cancers as well as blood disorders such as aplastic anemia.

In 1955, Thomas was appointed physician-in-chief at the Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital in Cooperstown, New York. Here he became fascinated by the discovery that rodents given a lethal dose of radiation could be rescued by an intravenous infusion of marrow cells from a donor. In 1957, Thomas treated a patient with leukemia using high doses of total-body irradiation to wipe out cancer, and then gave them an infusion of marrow cells from an identical twin. The transplant was at first successful, although the patient later died from a recurrence of leukemia. Many investigators left the field, pronouncing it a dead end. Thomas did not give up. Thomas set up his laboratory at the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Hospital in Seattle, which was affiliated to the University of Washington’s medical school. Under Thomas’s guidance, we spent the 1960s developing high-intensity irradiation treatments to eradicate patients’ cancer cells and establishing the importance of tissue matching for transplant outcome. Work with patients began in 1969 at the USPHS hospital. Initial survival rates were low, and unexpected problems required going back and forth between bench and bedside — something that remained a hallmark of Thomas’s work. There are patients who received transplants in 1971 still alive today. Progress has been slow but steady. Early marrow donors were siblings. In 1979, the first patient with leukemia was successfully treated with a transplant from an unrelated donor using new immunosuppressant drugs. This success sparked Thomas and others to set up international marrow-donor programmes. In 1972, the US government closed the USPHS hospital. This prompted the founding of the private Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (the Hutch), with close ties to the University of Washington’s medical school. “Virtually every major transplant centre in the world got its start by sending someone to train under Don Thomas.” Owing to his influence, the Hutch’s clinical focus has always been the patient, and its approach, one of teamwork. Rainer Storb is at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and at the University of Washington, both in Seattle. e-mail: rstorb@fhcrc.org