Football Bellard and the Wishbone

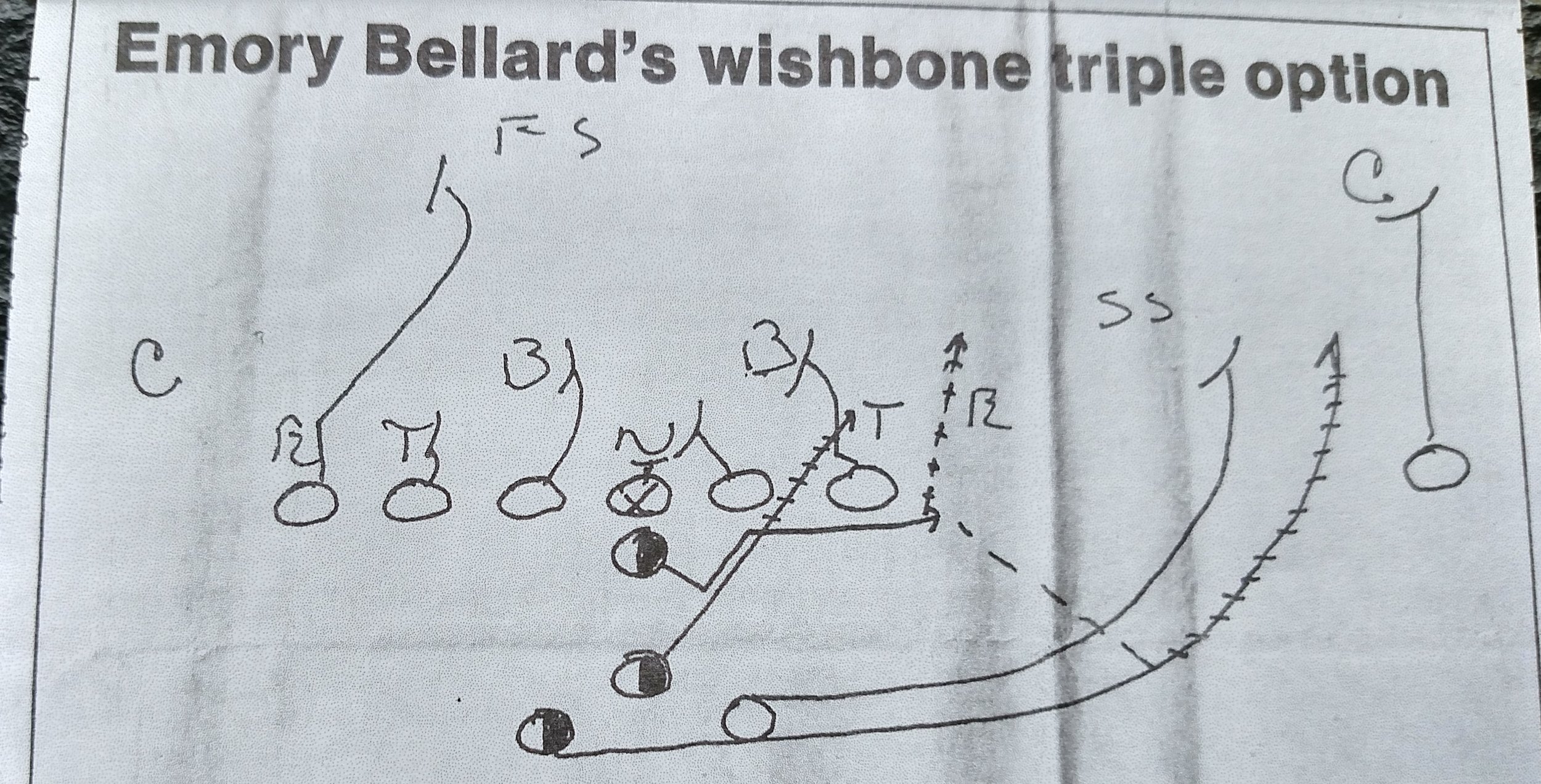

Before the Wishbone offense took center stage, the opposing defense’s job was to react and neutralize the offensive play. Emory Bellard changed the defensive strategy with the option offense by devising the first successful offensive college running scheme dictated by defensive decisions.

Neither offensive nor defensive players knew who would get the ball when the ball was snapped. As the play unfolded, the defensive decisions chose the ball carrier. It was magic, a James Street/Eddie Phillips/and Donnie Wigginton wishbone hat trick that led the Horns to national prominence.

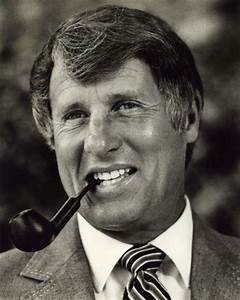

Pipe dreams — Remembering Emory and the Wishbone

Steve Estes

Agree! Coach Bellard is class. I talked to him when he was with the Texas Longhorns and Spring Westfield, some of those times when he was on recruiting trips, and others with Dave Campbell. Great interview, always. Polite! Informative! All-around nice guy. Great football mind. His development of the wishbone formation was genius. He put UT on the map. I never heard a bad word uttered against him—and that’s unusual. RIP.

Coach Teaff once said of Emory: “At a time … in the Southwest Conference when not everyone had that degree of integrity, he always did.”

I’ve read that Coach Royal said, “He was a true friend, and that didn’t change whether he was in Austin, College Station, or Starkville.”

Feb. 11, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Just two years ago, Emory had attended a Sportsman’s Club dinner previewing the Longhorns’ upcoming season and honoring the 1969 Texas National Championship team. His hair was snowy white, and the ever-present smoking pipe which had been his trademark was gone. Otherwise, he was the usual, ultimate gentleman. A master of the game and a citizen of the people. And in this space, I remember another place, and another time, when the faces of Texas Longhorn football, and the mindset of the college and the high school game, were about to change.

When the players tried it on the field for the first time, Street remembers saying with Bradley, “this ain’t gonna work….”

“Emory,” Royal recalled Thursday, “understood the game of football, and was a great coach. But beyond the X’s and O’s, he was a great teacher.”

A teacher, Street says, of more than just the game.

“Before every game he would tell me `stay steady in the boat,'” Street recalled. “‘Play every play like it’s a big play. Don’t worry about the outcome of the game. Just play every play like it’s a big play.'”

More than that, however, they will recall the patience of a pipe smoker, who in his own way was an artist of the game, as well as a teacher. There is a touch of sad irony as well. With Bellard’s passing, seven of the eight assistant coaches on that staff which changed the face of Texas football are gone. Tom Ellis, Bill Ellington, Mike Campbell, Leon Manley, Willie Zapalac, and R. M. Patterson preceded Emory in death. Only Fred Akers remains.

And through his legacy – like all of them – Emory, with his pipe and his yellow pad, his schemes and his dreams, will stand the test of time, not only for what he did, but for who he was–and the lives that he touched.

Melvin Pat Patterson

I am fan of Emory. We worked at Camp Longhorn in the summers. He ran the Camp for Tex Robinson. At night he would take those of us who were studying to be coaches to the chow hall and he would share football footage with us. Ray Frady worked for him at all the schools he worked at until he went to U.T. I learned how to coach from him I coached 9 years of high school football.

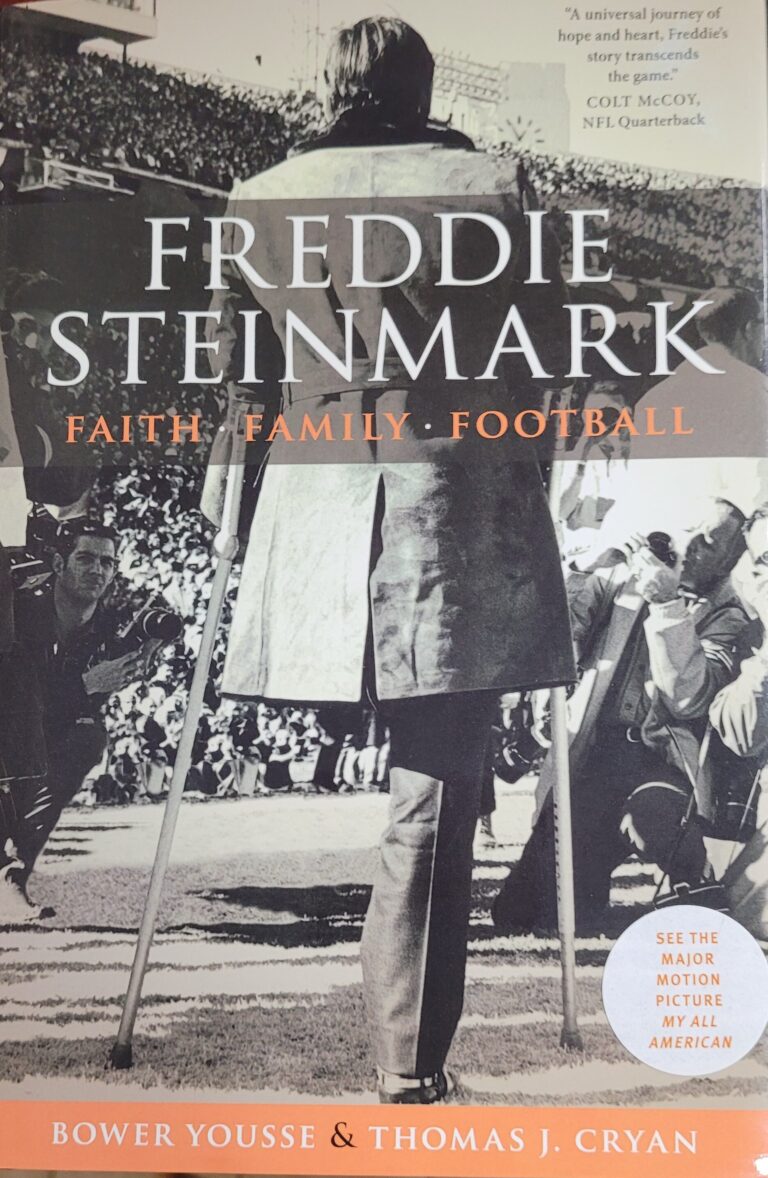

Emory Bellard plays for Coach Dana X. Bible at U.T. in 1945 but suffers a severe injury when his 165-pound body is hit by a team tackle that included 700 pounds of Dick Harris, Peppy Blount, and Ed Kelley. Something had to give, and it did! Emory’s femur broke, as Peppy Blount says with a sound as loud as a “75 -millimeter cannon”. Emory Bellard’s playing career was over, but his high school and college coaching contributions were beginning. From his excellent football mind, one of the most dynamic offenses in the history of college football is born.

“After a successful career as a high school coach, he returns to Texas in 1967 as an Assistant Coach. Coach Royal moves Bellard to offense and ask him to develop an offense that involved more of the Longhorn talented backs.

Coach Bellard does as instructed and devises an offense that is simple conceptually but difficult to execute. Since NCAA rules prohibited players work on formations out of season, Bellard had his son round up some high school friends with graduated Longhorn quarterback Andy White and Denny Aldridge who had played for Royal to help perfect the formation. Denny says “One clear memory is during the summer of ‘68 Royal called Denny requesting that I show up at Gregory Gym. the memory of being the wishbone fullback, Coach Bellard the quarterback and Royal was the defensive tackle.” Bellard and Royal were “going over the intricate details, i.e. alignment, stance, footwork, reads, and the pitch,” It was during this time the wishbone was born.

If the quarterback has to think about his option with the Wishbone, more likely than not, the play will fail. The wishbone requires practice, practice, and more practice to execute correct instinctive, automatic responses.

In 2021, my wife and I left Austin and relocated to Ingleside, just outside of Corpus Christi. As we drove down West Main Street one day, I slammed on the brakes when I saw a street sign for Emory Bellard Avenue!

Bellard began coaching at Ingleside High School, a Class B school in Ingleside, Texas. He guided the school to two consecutive regional wins (as far as Class B football went) in 1953 and 1954, and a street near Ingleside High School is named after him.

Many people think the Wishbone started in 1968, but the origin of the option offense was conceived in 1954 from the genius mind of Coach Bellard and implemented in various forms in his early years as a high school coach. Others in both high school and college were using a option read running format. In fact , when he presented the triple option offense to DKR , he didn’t even think the offense was revolutionary enough to name it. Bellard just called it the right-left offense.

In the book, The Die Hard’s Fan’s Guide to Longhorn Football Emory Bellard receives the accolades he deserves as the “Father of the Wishbone.”

If not the best offensive formation of all time, it is close. Oklahoma, Texas, and Alabama win national championships with the Wishbone, and Nebraska, UCLA, Air Force, Texas A & M, and Arkansas use either the original or a derivation of the Wishbone to re-invigorate their offense. In the ’70s, only two teams win more than 100 games, and both ran the Wishbone- Alabama and OU. Even Duffy Daugherty, the Michigan State coach, called DKR and ask for information on the new offense, and Royal said to Duffy, “You don’t want my offense. You want my fullback.” The Wishbone makes it possible to outnumber the defenders on every play, and that is how you win games on offense.

THE STORY FOLLOWS.

Jake Trotter ESPN Staff Writer July 24, 2018 says in the article

Emory reluctantly teaches the nuances of the wishbone to both OU and Alabama.

The Sooners had fallen on hard times under Chuck Fairbanks and had just lost at home to lowly Oregon State in Week 3 of the 1970 season. As “chuck Chuck” bumper stickers surfaced all around the state, Switzer, as he had that spring, begged Fairbanks to switch to the Wishbone with the Longhorns up next.

“Chuck said, ‘No, we don’t wanna do that. We don’t want to be a copycat to Texas,'” Switzer recalled. “S—, everybody copies everybody. We shouldn’t let that keep us from doing it.”

Desperate, Fairbanks relented. And to Bellard’s dismay, Royal agreed to help his alma mater — even with the Red River Showdown on deck.

“This still amazes me about Darrell, that he allowed Emory Bellard to talk to me,” Switzer said. “Emory was very, very helpful with me in discussing the finer points of the offense, blocking schemes and the corner and all that.

“I don’t know why Darrell did it. I can’t answer that. Maybe he felt sorry for our ass. I guarantee, he wouldn’t have done it if he knew what we were fixin’ to become.”

What Oklahoma became was a juggernaut.

Utilizing Switzer’s supersonic version of the Wishbone, the Sooners, beginning in 1971, rolled to five straight wins over Royal on the way to national championships in 1974 and 1975. Switzer, who took over for Fairbanks in 1973, would win another title with the Wishbone in 1985, with Oklahoma’s big touchdown in the Orange Bowl victory over Penn State actually coming on a pass to tight end Keith Jackson.

“The difficult thing about the Wishbone was, in order to stop the option game, you had to involve your secondary,” said former Nebraska coach Tom Osborne, who later would incorporate the option into his I formation, igniting the Cornhuskers to national championships in 1994, 1995 and 1997. “You couldn’t play the fullback, the quarterback keep and the pitch just by defensive linemen and linebackers alone. You ran out of people. And so it involved somewhat of a desertion of your secondary. And that really left you very vulnerable to the play-action pass because the secondary had to commit itself very quickly. And so one of the scariest things about playing Oklahoma was the play-action pass.”

Behind the Wishbone, the Sooners quickly regained control of the Big Eight from Osborne’s Cornhuskers……..” I

Jake Trotter ESPN Staff Writer July 24, 2018 says in the article he wrote about the wishbone that

“After witnessing the Sooners rush for 349 yards against his defense in the 1970 Bluebonnet Bowl, Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant flew to Austin the ensuing spring to learn the offense from Royal and Bellard.

“Bryant comes to Austin and the next morning they’re going to get started,” Herskowitz said. “Darrell gets to the football building and Coach Bryant is outside sitting on the steps. Darrell said, ‘Paul, how long you been sitting here?’ And Coach Bryant said, ‘Since 6 o’clock — when do you guys go to work around here?'”

Following consecutive five-loss seasons, the Crimson Tide immediately rebounded and went undefeated before falling to Nebraska in the Orange Bowl. Two years later, Alabama captured the national championship, then added two more national titles to close out the decade. “They started kicking the hell outta everybody, too,” Switzer said.

From there, the Wishbone spread to every corner of the country. Even the rival Aggies relented, hiring Bellard to bring the Wishbone to College Station in 1972 after four consecutive losing seasons. Within three years, Bellard had Texas A&M in the top five in the polls.”

Billy, I saw a video of a dinner roast of Emory Bellard shortly before his death. Spike Dykes was speaking and related that he got his first job under Coach Bellard at San Angelo Central as a JV coach. He said that one day in practice he had been giving a center too much of a difficult time. After practice that day, Coach Bellard pulled Spikes aside and said, “Coach, we do not have anyone else to play center; however we can find someone else to coach!” It brought down the house! Charlie Templeton

The testing of the option for the Longhorns offense was perfected by Andy White and then presented to Coach Royal. DKR approved the offense, and the rest is football history.

Coach Bellard understood that the new Wishbone option offense could not succeed in a vacuum. He knew the Wishbone’s success required a strict discipline of practice, more practice, repetition, and more repetition.

In the book, Wishbone Wisdom, the author, Al Picket, says that Emory Bellard believed that the greatest coaches came from the high school ranks (Royal felt the same way). Pro’s have many ways to access talent, and colleges can recruit athletes to fit their system. Still, high school coaches must develop strategies and use the talent pool that is available and consequently have to adjust and “stress the points that will help different high school kids get better.”

Jake Trotter says, “Emory Bellards Wishbone is still having an impact today. Emory Bellard totally impacted what I do,” said Washington State coach Mike Leach, who credits the Wishbone as a bedrock for his Air Raid spread passing offense, which, like the Wishbone once did, has proliferated across college football this century. “[It’s] one of the greatest offenses of all time … and odds are extremely high that if I didn’t run the Air Raid, I would run the Wishbone.”

Coach Bellard died on Feb. 10, 2011, at age 83 of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease), but his contributions to Longhorn traditions remain a portal to the past reminding Longhorn fans that heritage shapes the present and empowers the future. Coach Bellard is a bridge builder.

08.13.2010 | Football Bill Little commentary: Monsignor Fred Bomar — The Stone and the Fiber

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

The other night as I watched the vintage movie channel’s version of the western classic The Magnificent Seven (probably for the 400th time or so), my wife Kim walked through the room and paused for a minute.

“The amazing thing to me,” I said to her, “is that the actors pretty much have all died, and yet they seem so alive.”

The preface to the book is a single quote from Pericles, the leader of Athens during its Golden Age from 495 to 429 BC.

“What you leave behind,” he said, “is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others.”

Emory’s illness …….. remind us that life is fragile. Our memories capture the value of a moment, and the image of a time gone by. And in that space, they will always live, and they will always matter.

Because they are both the stone, and the woven fiber, in the mosaic of life.

Tales of Emory Bellard as told by Horns , Aggies, and Sports writers

Slocum comments on his head coach Emory Bellard.

In the book “Back Yard Brawl” by W.K. Stratton, Slocum credits Emory with the improvements in Aggie’s facilities. Still, Slocum says the most important building that went on under Bellard involved the kind of players he recruited.” He led the charge in recruiting African American players.

R.C Slocum was an assistant Coach under Coach Bellard at Texas A & M. He was devasted when Emory left A & M saying “I don’t know that he was fired. But whatever happened, it was one of the biggest disappointments of my career. I thought it was a tragedy fro Emory to leave the university when he did.”

Special Memories of Emory Bellard from Ed Simonini #77.

Ed Simonini brought the Texas A&M “Wrecking Crew” into the national spotlight with a 1975 Lombardi nomination. The TAMU three-time annual leader in tackles (130 in 1973, 98 in 1974, and 101 in 1975) made 425 career tackles for the Aggies. Among his many athletic achievements are:

Second Team All-American, 1973, 1974

Second Team All-American, 1973, 1974

Consensus All-American linebacker, 1975

All-SWC Linebacker, 1972, 73, 74 & 75

SWC All-Decade Team

SWC Freshman of the Year, 1972

SWC Defensive Player of the Year, 1973 & 75

Houston Post MVP Award, 1973 & 75

3rd Round Draft Choice, Baltimore Colts, 1976

Dear Billy,

Though we’ve never met and went to “opposing” schools, we share a love for Emory and how he “coached” his players. Next to my father there was no other person that influenced more my thinking or development as a young adult. I was privileged to be one of several former players asked to speak at his funeral and told 2 stories that reflected what kind of a person Emory was.

#1 You may remember the undefeated 1975 A&M team that played Arkansas in Little Rock at the end of the year instead of the “traditional” game versus t.u. Total fiasco for us, the “pigges” just kicked our butts. No National Championship, No SWC Championship, No undefeated season, lots of we should have never changed the traditional schedule” and second guessing. You’ve been there and know what I’m talking about. Afterwards all the reporters are hammering Emory with their typical “well coach, how do you feel right now” type questions. Instead of cutting them off, getting angry or refusing to answer, Emory is answering every question. Soft spoken, head down but never once losing his temper or acting out. They must have grilled him for at least 20 or 30 minutes and he answered every question!! Then he travels back to College Station, deals with a new group of reporters, alums, students and fans. Not once did I see him lose his composure, or blame anyone but himself for our loss. Take away – Do your job. No matter the circumstances, it’s your job and your responsibility.”

#2 Remember your off-season conditioning, lots of running stairs, 40’s, weights, etc., right? At A&M someone had the bright idea to have players by position run 220’s, walk across the football field and run another, walk across, etc. etc. We’d run 10 or 15 220s but it was ok because we’re all grouped by position and nobody could or would run much faster than anyone else. It’s all good, right? And then Lester Hayes gets recruited and signs with A&M as a LINEBACKER!! This is the state 220 champion and all us slow, dumb LB’s are chasing his ass while he’s laughing, practically running backwards. Of course, the coaches are yelling at the stragglers (everyone but Lester) to stop “dogging it”, run faster, etc. So now we’re all running like crazy and my foot is kicked by another player, I go down, stick my arm out to break the fall and pop my elbow out the opposite direction, OUCH!! Well, the 1st person to reach me was Emory. He sees my elbow and he gets on his concerned frown face. He takes my elbow, moves it back and forth and tries to push it back in place, DOUBLE OUCH!! I tell him it’s not going back in but damn if he doesn’t push on it again, YIKES!!! Thankfully Billy Pickard, our trainer, arrives and takes over. But now as Emory starts to stand up, he gets that goofy smile on his face, looks right at me and says, “Gosh darn it Ed. You’d do anything not to have to run those 220’s”!! Take away – No matter how much it hurts, never lose your sense of humor.

Ed Simonini

Thanks again for bringing these memories back to mind. I doubt if you heard this story but truly it tells you that no matter what, Emory cared about his people.

At the end of the 75 season, Emory and I are in Houston for the Lombardi Award ceremony that night. We get to the hotel and he tells me to meet him back at his room after I get dressed (1st time in a tux!!). An hour or so later, I’m knocking on the door to his room. As soon as he opens the door, I know something is wrong because he has his frown face and I’d just left him an hour ago when he was smiling, laughing and joking. Emory tells me several players had been arrested at an off-campus party where marijuana was present. Most of the players were seniors and like me, we’d had played our last down at A&M. When we get back to campus, Emory goes to the jail and posts bail and arranges for a lawyer. Nobody is kicked off the team, every player finishes their last semester at school and they were all acquitted. Could not imagine a current coach in that situation doing the same thing. Ed Simonini

End of Ed’s Comments

Sports Writers

Sports Writers

Mickey Herskowitz initially named the new offense the “pulling bone,” and it was then shortened to the “Wishbone:”

Hugo Kugiya from the Seattle Times said that “the wishbone did so much for the well being of so many Texans, Emory Bellard might as well have invented the light bulb or the telephone.”

Dave Barron from the Houston Chronicle said on August 23, 1993, that “Listening to Emory Bellard lecture on the wishbone- or on any aspect of Texas football, for that matter- is about as close as anyone can get…. to Moses in coaching shorts.”

Jake Trotter ESPN Staff Writer July 24, 2018

AUSTIN, Texas — One of the most revered terms in the college football lexicon owes its existence to a hotel that no longer exists.

The Villa Capri once adjoined the University of Texas campus and boasted one of Austin’s in-demand restaurants. The dining room, with brass-rodded chandeliers above, featured a broiling pit at the center, where a chef charcoaled choice steaks. Outside, burnt orange umbrella tables and lush grass surrounded the hotel’s pool.

But the place to be at the Capri on autumn Saturday nights was Room 2001, where legendary Texas coach Darrell Royal would hold court and drink booze with reporters and luminaries — including actor John Wayne once — in town to watch the Longhorns.

And 50 years ago this season, it was in Room 2001 that the “Wishbone” was officially christened — forever changing college football.

Earlier that summer, Royal had tasked assistant Emory Bellard with devising an offensive scheme that would revive the moribund Longhorns and remove Royal off a seat that was heating up after a third consecutive mediocre season.

The pipe-smoking, yellow-pad-doodling Bellard, who just two years before had been coaching high school, returned to Royal with a rather unorthodox proposal: What if, to capitalize on its wealth of running backs, Texas placed three rushers in the backfield?

Bellard’s three-back, triple-option attack didn’t have its name yet. But the “Wishbone” would go on to catapult Texas to back-to-back national titles, relaunch dynasties at Oklahoma and Alabama and, eventually, transform offensive football at every level of the game.

After corralling Navy and Heisman winner Roger Staubach in the Cotton Bowl for the 1963 national title, Royal’s Longhorns rapidly tumbled off their perch. Texas went 6-4 in 1965, then 7-4 the following year. The Longhorns still opened the 1967 season with promise and were ranked in the top five in the polls. But Texas spiraled again late, which culminated with a deflating 10-7 loss to rival Texas A&M.

Royal — who fashioned the phrase “three things can happen when you throw the ball, and two of them are bad” — loathed passing. But in running into wall after wall out of the I formation, Texas averaged just under 19 points a game in 1967 despite having 1,000-yard running back Chris Gilbert as its centerpiece.

“We just tried to outmuscle everybody,” Gilbert said. “That grew old and was about as conservative an offense as you could have.”

Royal might have delivered Texas its first national title five years before. But now he was under immense pressure from the boosters and students to win again — which would be underscored by the effigy of his likeness left hanging at the practice field after Texas failed to win either of its first two games in 1968. Such budding pressure would prompt the otherwise conservative Royal to rubber-stamp a drastic change, though not before putting his team through a spring practice so brutal his former players still quiver at the thought of it.

“That spring, he called us together and said, ‘Boys, we’re not going to be 6-4 this next year. We may be 0-10, we maybe 10-0, but we’re not going to be 6-4,'” remembered running back Ted Koy. “It was the most hellacious spring training. I mean, it was a bloodletting.”

Quite literally, in fact. During one unforgettable drill, fullback Steve Worster slammed headfirst into future All-American defensive end Bill Atessis, triggering a hit so vicious it cracked Worster’s face mask in half while also breaking his nose. With blood gushing down his face, Worster was handed a towel — then another helmet so he wouldn’t miss his turn.

Yet for all the consternation around the program, the Longhorns entered that offseason stacked in the backfield.

Gilbert was coming off back-to-back 1,000-yard seasons thanks to “an uncanny balance,” Koy said. “He’d be hit, knocked off balance, and he’d put his hand down and get an extra 3 or 4 yards.”

Worster, who had produced 28 consecutive 100-yard rushing games in high school for Bridge City — still third all time in Texas history — was among the highest-profile recruits Royal had ever snagged.

“Tougher than nails,” Koy said. “Steve did not have the blazing speed but could be full speed in a few steps.”

“The big question was: What were they going to do with Worster?” said Bill Little, who was in his first of 50 years in Texas’ sports communications department that season. “And whether or not Koy or Worster was going to play.”

Having three talented backs was a good problem for Royal to have. And out of this problem came Bellard’s solution, which would soon alter Texas’ fate.

Emory Bellard grew up in a small town east of San Antonio and began coaching high school football in 1949. He won three state titles, and the last of them, for San Angelo Central in 1966, convinced Royal to hire him, initially to man linebackers.

“There’s no one who loved coaching more than Emory,” said former Texas A&M head coach R.C. Slocum, who was hired in College Station as an assistant by Bellard. “He was just an amazing guy. Loved the game of football, loved coaching, loved kids.”

Emory Bellard was well-respected among his peers as an innovator.

Slocum swears that Bellard never cursed once during his entire coaching career. But he did keep one vice: a tobacco pipe, whose smoke would signal through the halls of the football building when he was working away in his office.

“In coaching circles, Emory Bellard was respected by everybody,” Leach said. “They knew that Emory Bellard knew more than they did and was a better coach than they were.”

After the disappointing 1967 season, Royal shook up his staff and flipped Fred Akers to defense and charged the impressive Bellard with the monumental assignment of fixing the offense.

Bellard initially championed the Veer that coach Bill Yeoman had perfected at Houston. But Royal vetoed that suggestion because the Veer, which had split backs, didn’t have a lead blocker. So as his colleagues went golfing that summer, Bellard went back to the yellow pad.

“He was a grinder when it came to working,” Slocum said. “But he was perfectly happy doing that.”

Little remembers walking the football halls one summer day when he detected Bellard’s pipe smoke cascading through the doorway of his office. Little inquired if Bellard had decided on Worster or Koy. Bellard replied, “What if we played them both?”

Bellard pointed to his pad, which had three circles in the backfield in the shape of a Y. Worster would be the fullback, lined up behind the quarterback; Koy and Gilbert, the halfbacks, split behind. By utilizing option principles of the Veer, Bellard explained that the quarterback would have three choices. 1) hand the ball off to the fullback on the dive; 2) keep the ball around the end; or 3) pitch it to a halfback streaking from the backside, with the other halfback blocking for him — all quarterback reads determined by how the defensive linemen reacted. The formation was balanced, capable of running equally as effectively in either direction. And it met Royal’s request of incorporating a lead blocker. With Royal’s ratification, Bellard brought his yellow-pad concoction to life, perfecting the spacing and running lanes in the basketball gym, using whatever athletic department staffers he could borrow as dummies. When the players returned for camp, he summoned the quarterbacks to the cafeteria. “He had salt and pepper shakers out, showing how it was going to work,” said Eddie Phillips, who would eventually become Texas’ starting quarterback in 1970. “The visuals were pretty good, but it was a little bit unusual.” That preseason, the Longhorns exhaustively practiced two running plays: the triple-option and the counter, which was needed to punish any defense that over-pursued. Nobody, not even Bellard, could know whether this new offense would work. And through much of the first two games, it didn’t work one bit. The Longhorns were fortunate to tie Houston in the opener. Then, things went from bad to worse in Game 2 at Texas Tech, as the Longhorns trailed 21-0 at halftime. Texas, however, would make two essential adjustments moving forward. And it would be 30 games before the Longhorns would lose again.

Bill Bradley was one of the most celebrated all-around athletes from the Lone Star State in the mid-1960s. He could throw with either arm and punt with either foot. Despite being drafted in the seventh round by the Detroit Tigers, Bradley went to Texas and summarily became its starting quarterback.

“He was so good at everything, he could punt, he could do whatever,” said Little, who dubbed him “Super Bill” while writing for the Austin American-Statesman. “Bradley was a total superstar.”

Bradley, however, had suffered a knee injury in 1966 and hadn’t quite regained that superstar first step two years later. He also had trouble with the reads and pitches paramount to the triple-option and tried too often to make the big play instead of the correct one.

“It just wasn’t honed up,” Bradley said. “I wasn’t making the right decisions at the very beginning of the play.”

Bradley’s best friend on the team was backup quarterback James Street, who carried a similar swagger. During the summers, the two worked together on a ranch in East Texas. Like Bradley, Street was a baseball player and pitched both a perfect game and a no-hitter for the Texas baseball team.

“James was very charismatic, had a spirit about him that was contagious,” Koy said. “If you were going to shoot marbles, you’d want James on your team. You just had confidence in him.”

With the game slipping away at Texas Tech and the Wishbone still scuffling, Royal grew frustrated with Bradley. Finally, in the second half, he turned to Street and said, “Get in there. Hell, you can’t do any worse.” As gifted as Street was on the diamond, he was born to run the Wishbone, which magically began to hum with him as the conductor. Remarkably, Street nearly led the Longhorns back, until a late fumble ended the rally. “James was built for it,” Bradley said. “So deceptive with the ball. It was a perfect match.” The following morning back in Austin, Bradley got a knock on his dormitory door. A manager was on the other side, saying Royal wanted to see him. Bradley knew what that meant. Street was now the starting quarterback. After leaving Royal’s office crying, Bradley called his dad, wanting to quit. “My dad was a hard, railroad man and a baseball coach,” Bradley said. “He told me, ‘You’re not welcome in this house if you do.'” Bradley would eventually find a new home at defensive back, where he would become a three-time Pro Bowler for the Philadelphia Eagles. Texas, however, still had one more revision to make. As he studied film of the Texas Tech game, offensive line coach Willie Zapalac noticed Worster was getting to the point of attack before his linemen could deliver their blocks. Worster was also getting there without a full head of steam. Bellard and Royal agreed that by taking a step back, Worster could morph into the human-battering ram the Wishbone pined for him to be. “When we moved Worster back and James took over,” Bradley said, “We just caught fire.” Two weeks later, in Dallas, trailing by a point to Oklahoma with just a couple of minutes remaining, Street took the Longhorns right down the field with a series of completions. Worster then did the rest. He slammed past the right guard on the dive, plowed over an Oklahoma defender, then dragged two more Sooners into the end zone for the game-winning touchdown. “We started tearing people up,” Worster said. “They didn’t know how to defend the Wishbone. They didn’t know what to do, and we loved it.”

The following Saturday, Texas put up 39 points in another win against another rival, this time ninth-ranked Arkansas. Back in Room 2001 of the Capri, Royal had a Budweiser in hand, when somebody asked, “Darrell, what are you going to call this offense?” Houston Post writer Mickey Herskowitz chimed in that the formation looked like “a wishbone.” From then on, that’s what Royal called it. “I had already used it my story that night, so I wanted to get credit for it,” Herskowitz said. “I told Darrell later, if I realized you were going to give me credit, I would’ve been charging you a royalty — no pun intended.” The offense that would engulf college football like a wildfire had its name. Emory Bellard, at Royal’s urging, taught the Wishbone to Barry Switzer, and Oklahoma became one of college football’s powerhouses under Switzer’s watch. AP Photo/Mark Foley Propelled by its Wishbone, Texas captured back-to-back national championships in 1969 and 1970. Paying attention across the Red River was Oklahoma offensive coordinator Barry Switzer. “They’d always outnumber you when they executed,” Switzer said. “Didn’t matter what you did.” The Sooners had fallen on hard times under Chuck Fairbanks and had just lost at home to lowly Oregon State in Week 3 of the 1970 season. As ” Chuck” bumper stickers surfaced all around the state, Switzer, as he had that spring, begged Fairbanks to switch to the Wishbone with the Longhorns up next. “Chuck said, ‘No, we don’t wanna do that. We don’t want to be a copycat to Texas,'” Switzer recalled. “S—, everybody copies everybody. We shouldn’t let that keep us from doing it.”

As Slocum tells it, years after they had both retired, Royal phoned Bellard out of the blue.

“Do you remember that day I came into your office and told you I wanted you to help OU run the Wishbone — and you told me you didn’t think we ought to do it?” Royal said, Bellard told Slocum. “I’ve had a long time to think about this — and you were right.”

SWC and the Wishbone

Over the 1970s, only two programs finished with more than 100 victories, and both of them — Oklahoma and Alabama — ran the Wishbone for virtually the entire decade. Today’s run-pass option plays in spread offenses owe a debt to Emory Bellard’s Wishbone. Courtesy of UT Athletics In 1988, the Villa Capri was demolished to make way for new Texas practice fields. The Wishbone, as Bellard constructed it, would survive only for a little while longer. It died at Texas more than a decade earlier when Royal retired in 1976. Ironically, the Longhorns replaced him with Akers, whom Royal had shuffled to defense in 1968, clearing the way for Bellard to doodle the Wishbone into existence. After returning to Austin from Wyoming, Akers scrapped the Wishbone at Texas for good — save for one play in 2012. When Royal passed away that November, Texas coach Mack Brown honored him by having the Longhorns line up in the Wishbone on the first play against Iowa State, which turned out to be a 47-yard completion off a trick play. “If you do something to change the direction of college football, it’s a legacy,” Brown said of Royal and Bellard, who died a year before Royal, in 2011. Although just a handful of schools, such as Georgia Tech and the service academies, primarily employ the option, the legacy of the Wishbone lives on. “Some of the original spread guys, Chip Kelly to Urban Meyer, their principles are based on numbers. They try to outnumber you,” said Navy coach Ken Niumatalolo. “The Wishbone was based on numbers. You pitch off this guy; this guy is your read key for the dive. Getting the numbers advantage is a principle of the Wishbone. … and its fingerprint is still heavily involved in football today.” That includes the run-pass option, which allows the quarterback to pass out of a running play if he sees a numbers advantage. The Philadelphia Eagles utilized an array of these, called RPOs, in their upset of New England in Super Bowl LII. “Those are remnants of what Darrell and Coach Bellard came up with back in the ’60s,” Brown said. “You still see what they came up with impacting the college and NFL game today.”

At the ground floor of constructing the Air Raid at Iowa Wesleyan, Leach and Hal Mumme carefully studied the Wishbone together and implemented its concepts into their offense.

“One thing with the Air Raid that’s very important is to make sure all the skill positions touch the ball,” Leach said. “In the Wishbone, all the skill positions touch the ball. All the skill positions contribute to the offensive effort. From the Wishbone, we drew the concept of distribution.”

With its success, the Air Raid has since taken over as college football’s attack du jour. Switzer, however, isn’t so sure the Wishbone couldn’t also still thrive today.

“Think about the quarterback that won the Heisman at Louisville [Lamar Jackson],” Switzer said. “S—, he’d be perfect in the Wishbone. There’s a lot of them out there, with the great speed and quickness that can also throw the football. They’re out there by the dozens. They’re just playing different positions.”

Leach, whose offense just led the nation in passing attempts for the sixth straight year, isn’t so sure, either — that still, 50 years later, Bellard’s brainchild, in its original form, couldn’t flourish.

“Nobody has ever truly stopped the Wishbone,” he said. “There’s a point to where people have lost interest in the Wishbone. But nobody ever really successfully stopped it.”

End of Jake Trotters Great Article TLSN is a 501 (c) (3) tax exempt

One Comment