Eyes of Texas

The Eyes of Bevo are upon you.

This whole discussion is quite simple for me. No one sings the Eyes of Texas to salute racism. Over the last 55 years, I had no clue that the words might be indirectly perceived as racist. The song is the heart and soul of a diverse university that most Horns share with equal pride. The song brings tears to my eyes and tightness to my throat as I proudly sing with 100,000 other Longhorns the “Eyes of Texas.”

WHAT SOME PAST LONGHORNS HAVE SAID ABOUT “THE EYES. “

1995 Captain Stonie Clark says, “In the event of my untimely demise, open my casket and play “The Eyes of Texas.” If tears don’t well up in my eyes and the hair on the back of my neck doesn’t stand up, you can rest assured I’m gone, off to the 40 acres in the sky.

James Brown said, “the University has done a lot for me. It gave me confidence in the business world, and it has been a big part of my life. I have learned what “The eyes of Texas” are. When I was playing, I didn’t, and now I see the full scope of everything.

Billy Dale said, “if I only have one choice to either watch the Longhorns play football or sing the “Eyes of Texas,” I am singing.

Phil Dawson “My approach when I got there (Texas) was that the work was just beginning. I was humbled by the opportunity to run out in that stadium and hear everybody singing “The Eyes of Texas,” to wear the helmet and be part of that history.

Author Larry Carlson says in an article he wrote about football great Lance Taylor “ When Lance Taylor talks about the University of Texas, you can almost hear the strains of “The Eyes of Texas” in the background. His eyes light up, he talks a bit faster; the enthusiasm is hard to contain.” “Taylor is reminded what a psyche-out it must be for teams visiting Memorial stadium when the band plays “The Eyes of Texas”. A ritual in which the squad joins in with the Hook’em Horns held high. Lance says “ I think it gives the opponents great respect for our school.” Very few schools in the country can match our tradition.”

The following quotes are from a few pages of Margaret Berry’s book “UT Austin: Traditions and Nostalgia.”

Margaret is a UT historian. The book was written to honor a UT professor. Nothing racist at all. The president ended his speeches to the students with “The Eyes of Texas.”

To the Students of the University of Texas, 1899 U.T. President Prather would state at the end of his remarks to the U.T. student body “The Eyes of Texas are Upon you.” Always a figure of perfect dignity and stateliness, he had heard president Robert E Lee say the eyes of the South are upon you. Prather paraphrased the remarks for Texas students.

John Sinclair, a University student in 1903, was the campus poet. Because he was extremely talented with the banjo, he took part in a campus minstrel show given as a benefit for the varsity track team at the Hancock Opera House on May 12. The night before the show opened, Lewis Johnson, Sinclair’s roommate and director of the band, decided the show needed one more peppy song to put it over. The president’s words were recalled, and that night Sinclair composed the song on a piece of wrapping paper torn from the Bosche laundry bundle.

Words were fitted to the tune of “I’ve been working on the railroad. ” His song was a great success when first sung at the minstrel show by the University quartet whose members were J.R. Cannon, Jay . D. Kiblehen, Ralph Porter, W.D. Smith. Mrs. Mary Lee Prather Dardan, daughter of president Prather related to a student Reporter several years later.

It was first sung at a benefit show for the track team at the old Hancock Opera House . Dr. Daniel a. Penick, tennis coach and professor, directed the quartet that introduced the song.

During the minstrel, a very seedy-looking individual appeared wearing an A&M sweater and carrying a dilapidated old valise. The interlocutor demanded, “Say what you got in your bag?” “A boll Weevil. I gwine (going) up to the University to show it to the president. “What for?.” “He’s gwine (going) To make a speech to this here boll Weevil. He’s gwine to tell it the eyes of Texas are upon you. Before the song could be finished, Jim Cannon later recalled the audience was in an uproar. President Prather was the first to laugh. The audience called for many encores and joined in the singing until the quartet finally had to sing, “We are were tired of it.” Students left the theater humming and whistling the song. How well it was received was attested by the encores that were called for. As for Sinclair’s song “The Eyes of Texas are upon you,” it must be said that the words are taking that the singing of the quartet was really extraordinary.

The catchy tune immediately became the unofficial alma mater of the University. Until that time, students had used other college songs, but finally, Sinclair’s song became their own. In 1905 when president Prather died, the Eyes of Texas was played at his funeral.

In 1943 Coach Bible’s football team played favored Southwestern, so Bible resorted to non-football strategy to disrupt Southwestern momentum. Spot Collins with Southwestern said every time we had a good drive going or got near the Texas goal line, the Longhorn band would start playing The Eyes of Texas, and all the Southwestern players, out of respect, would take off their helmets and stand at attention. Texas still lost. 14-7.

When Sinclair died in 1947, it was played on the Tower Carillon at the hour of his funeral. The new University of Texas president HY Benedict had the song translated into ten foreign languages in 1930. In 1936 Ed Nunnally, a University student, organize a group to get the eyes of Texas copyrighted. Efforts culminated in securing a 28-year Copyright of the words and the arrangement. The music itself had long since been in the public domain and rightfully belonged to everybody.

In 1983 on the 50th anniversary of the Sinclair song, the original text was presented to the Ex-Students Association on permanent loan by Doctor James L Johnson and Lewis Johnson. Their father, Louis Johnson senior, had obtained the manuscript from Sinclair. Another copy, a silkscreen, was taken to the moon in 1969 By University ex-student Alan L beam. This prize copy is also at the Lila B. Etter alumni center on campus.

The students Association assumed it owned all rights to the song and collected royalties until January 30, 1964, when the Copyright expired. Impressive royalties were collected from various users of the music. The John Sinclair scholarship fund set up by an “Eyes of Texas” committee formed by the students Association after Sinclair’s death automatically received half of each royalty received; the Students Association kept the balance. The greatest sum received was $3000 from the producers of the Giant in 1956. Another $1500 came from the use of the song in the Alamo. Royalties were also paid for the song’s use in Lucy Gallant. “With a Song in my Heart,” “Night Train to Galveston,” and “Go for broke.”

When the time for renewal arrived, The University could not legally ask for a renewal. The author had died, and heirs could not be located. The Copyright lapsed, and the song again went into the public domain despite efforts made by the Students Association, The Ex-Students Association, and congressman J.J. Jake pickle.

UT students and the administrators were surprised in the late 1970s to hear that a man living in Oregon was claiming the ownership of the Eyes of Texas. A former Fort Worth fiddle player Wylburt Brown copyrighted the words in 1928 to become the official state song during the 1936 Texas Centennial. UT students and officials were unaware that he was collecting royalties on his version of the composition until 1986.

The UT History Corner is a great site that is full of wonderful information about the history of the University of Texas.

The link below will take you to the UT History Centers well-researched history of the origins of the “Eyes of Texas”. Click on the link below or read the story as shared after the link.

https://jimnicar.com/ut-traditions/the-eyes-of-texas/

The Eyes of Texas

In 1902, Lewis Johnson was the student manager for just about every musical performance on the campus. Between classes, he played tuba in the Varsity Band, directed the University Chorus, and arranged for concerts on the Forty Acres. Most were in the 1,500 seat auditorium of the old Main Building, but in late March, Johnson wanted to try something new and introduced a series of “Promenade Concerts.” Starting at 7 p.m., the band strolled along the walk that circled the campus and played a variety of overtures, waltzes, and new marches by a popular composer named Sousa. The crowd followed along, listened, clapped, danced, and occasionally sang. A roving party, the concerts were a great success. “This promises to be the most popular entertainment ever provided for ‘Varsity people,” declared the Texan student newspaper.

Among the songs, UT students sang were well-known college favorites: Fair Harvard and Princeton’s Old Nassau. But the University had no song to call its own, for years a sore topic regularly discussed in the student newspapers. Though not a composer himself, Johnson decided to find a way to create one.

He first contacted alumni known to have literary talent and hoped to recruit a volunteer to write a UT song but received only polite refusals. Not one to give up easily, Johnson turned to his fellow students, specifically to fellow band member John Lang Sinclair. Sinclair was an editor of the Cactus yearbook, a regular contributor to the University of Texas Literary Magazine, and was widely known as the campus poet. Sinclair resisted at first, but Johnson continued to pester.

One evening in early May 1902, Johnson and Sinclair returned from a comic opera performance in downtown Austin when they stopped at Jacoby’s Beer Garden, just south of the campus on Lavaca Street. Johnson brought up the topic of a UT song once again, and, perhaps with the help of Mr. Jacoby’s ales, Sinclair finally acquiesced to Johnson’s requests. They went to Sinclair’s room on the second floor of old Brackenridge Hall – popularly called “B. Hall,” the University’s first residence hall for men – stayed up all night, and finished the verses for Jolly Students of the ‘Varsity.

Music (and inspiration) came from the nationally-known tune, Jolly Students of America. Johnson contacted the composer in Detroit for permission to use the music, while Sinclair re-fashioned the words and extended the song to six verses. The chorus was:

For we are jolly students of the ‘Varsity, the ‘Varsity!

We are a merry, merry crew.

We’ll show the chief of all policemen who we are

Rah! Rah! Rah!

Down on the Avenue.

In the 1900s, the term ” ‘varsity ” was a contraction of the word “university.” In the Lone Star State, students who attended ‘Varsity, were understood to be enrolled in the University of Texas, while those studying at the “College” were in the A&M College of Texas (as Texas A&M was then called). In the chorus, the Avenue referred to Congress Avenue downtown.

The Jolly Students was introduced at a concert in late May, and the group was instantly popular with UT students. But Johnson felt the song still lacked a distinct Texas identity. The following spring, he prodded Sinclair to try again.

In March 1903, while Johnson waited in line at the University Post Office in the old Main Building, Sinclair arrived with a grin, quietly handed Johnson a folded scrap of brown paper torn from a wrapped bundle from Bosche’s Laundry in downtown Austin, and left. (Photo at left.) On it, scribbled in pencil with scratched-out lines and corrections, was the first draft of a poem:

They watch above you all the day, the bright blue eyes of Texas.

At midnight they’re with you all the way, the sleepless eyes of Texas.

The eyes of Texas are upon you, all the livelong day.

The eyes of Texas are upon you. They’re with you all the way.

They watch you through the peaceful night. They watch you in the early dawn,

When from the eastern skies the high light, tells that the night is gone.

Sing me a song of Texas, and Texas’ myriad eyes.

Countless as the bright stars, that fill the midnight skies.

Vandyke brown, vermillion, sepia, Prussian blue,

Ivory black and crimson lace, and eyes of every hue.

Before Johnson read the last line, he knew Sinclair had produced something for the University that would last long after their time as students had passed. Set to the tune “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,” Johnson and Sinclair prepared the song so the Varsity Quartet could perform it at its next show in May. As the work progressed, the two decided to make the song a spoof on UT President William Prather, and Sinclair made some significant revisions to the words.

Prather (photo at right) was a UT regent who was surprised by his fellow regents when they chose him to lead the University in 1899. He’d attended Washington College in Virginia (now Washington and Lee University), and often heard its president at the time, Robert E. Lee, tell his students, “Remember, the eyes of the South are upon you,” as he reminded them that they were the leaders of the future.

Prather particularly liked this phrase, though apparently, his talent for public speaking wasn’t popular with everyone. When Prather was tapped to be president, regent Russell Cowart wrote to his colleague, Tom Henderson, about the possibility of an inauguration ceremony for Prather: “I can see no reason why there should be any inauguration … I am afraid that the Dear Col. might inflict not only us but a suffering audience with a speech like the one he paralyzed us with when he came and was notified of his selection [to be president].” A ceremony was held anyway, and Prather concluded his talk with a plea to the students, “Always remember, the eyes of Texas are upon you.”

The speech was so well received, Prather decided to get all he could of it and ended most of his talks with the same phrase. The students, of course, picked up on it immediately, and it became an ongoing campus joke to chant, “Remember, the eyes of Texas are upon you!” at sporting events, concerts, and just about every social occasion. Prather took the good-natured kidding as it was intended. He knew that, at the least, the students were listening to him.

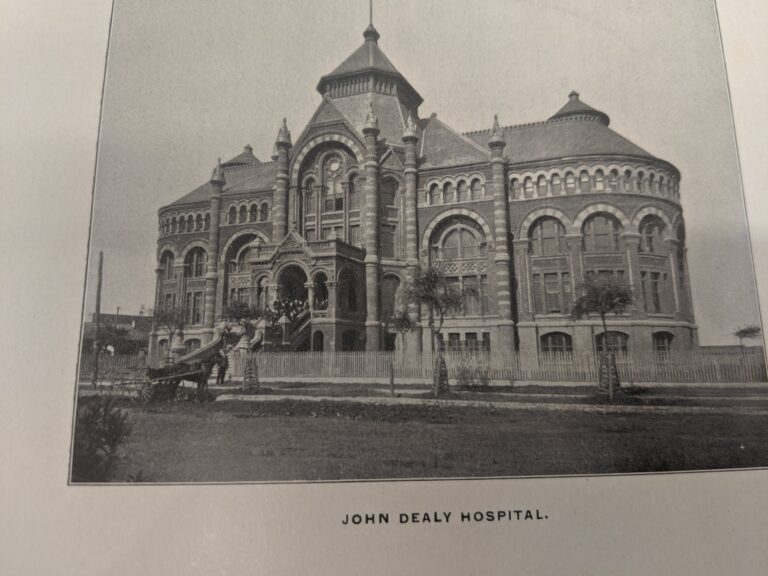

A Varsity minstrel show was scheduled for Wednesday evening, May 12, 1903, in the Hancock Opera House on West Sixth Street and was packed with music, dances, skits, and even a tumbling act. Proceeds from the show would pay for the University Track team to attend the All-South Track and Field Competition in Atlanta.

Leading off the show was an overture by the Varsity Band, followed by songs titled Oh, The Lovely Girls, Old Kentucky Home, and The Castle on the Nile performed by the University Chorus or student soloists. The fourth piece listed on the printed program was cryptically labeled a “Selection” by the Varsity Quartet.

With President Prather sitting in the audience, four students: Jim Kivlehen, Ralph Porter, Bill Smith, and Jim Cannon, accompanied by John Lang Sinclair on the banjo, took the stage and unleashed Sinclair’s creation:

I once did know a President, away down South, in Texas.

And, always, everywhere he went, he saw the Eyes of Texas.

The Eyes of Texas are upon you, all the livelong day.

The Eyes of Texas are upon you; you cannot getaway.

Do not think you can escape them, at night or early in the morn –

The Eyes of Texas are upon you, ’til Gabriel blows his horn.

Sing me a song of Prexy, of days long since gone by.

Again I seek to greet him and hear his kind reply.

Smiles of gracious welcome, before my memory rise,

Again I hear him say to me, “Remember Texas’ Eyes.”

Before the first verse was finished, the crowd was in an uproar. By the end of the song, the audience was pounding the floor and demanding so many encores that members of the quartet grew hoarse and had to sing. We’re Tired Out. The Varsity Band learned the tune, and the following evening included The Eyes on its Promenade Concert around the campus.

(The earliest recording of The Eyes of Texas was made in 1928 by the Longhorn Band. Listen to it – as well as the first recording of “Texas Fight” – here.)

Prather, though, had the last laugh. Less than a month after the minstrel show, on June 10th, spring commencement ceremonies were held in the auditorium of Old Main. Prather made his farewell speech to the senior class and turned the joke back on them. “And now, young ladies and gentlemen, in the words of your own poet, remember that the eyes of Texas are upon you.” The seniors gave Prather a standing ovation, and the University of Texas had a song.