Faustian moments – power, politics, and money destroy amateurism (Copy)

TABLE OF CONTENTS TO THE HISTORY OF RECRUITING INFRACTIONS – 1960-2020

-

The 1960’s-

-

The 1970s, the prequel to flagrant NCAA rules violations in the 1980s-

-

1980s SWC Recruiting Violations run rampant-

-

1990’s REGULATING INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS –

-

#5 2000s Infraction transitioning –

-

Judging intangibles is where Coaches make the most recruiting mistakes – The Good Egg-

-

RECRUITING STORIES

#1 1960’s

1964-SMU was punished for recruiting violations and retaliated by filing charges against most other schools in the SWC. Texas received a year’s probation without sanctions for some minor infractions, including:

-

excessive visits with a prospect,

-

failure of an alumnus to accompany a prospect on the flight of his private airplane to Austin,

-

payment of expenses of a friend of one athlete, and excessive entertainment.

U.T. was so upset with the petty violations that, for the first time, hinted they might leave the SWC and join a “superconference.”

The NCAA rules were made when most college players were white and had financial help from their families for things like dating, movies, and dinners. But by the 1970s poor and minority students started receiving scholarships that included room, board, and tuition but no extra spending money was available from their families to enjoy the college experience.

1968 – NCAA divides college divisions into I, II, and III

#2 1970’s the prequel to flagrant NCAA rules violations in the 1980’s

Cash in unmarked envelopes, cars, free trips, do-nothing summer jobs, new clothes, jobs for mom and dad infringed on the integrity of SWC college sports. Sportswriter Dan Jenkins referred to these years as the “money whipped” recruiting generation. Texas had a few minor infractions and Royal said “We’ll take our slap on the wrist, and go on.”

In the early 1970s, the NCAA members decided to create divisions, whereby schools were in divisions that would better reflect their competitive capacity.

In 1971 O.U. received a “private reprimand over high school recruiting.

In 1973 the NCAA cracked down and OU was put the football program on probation for two years for altering high school transcripts. O.U. was forced to forfeit 8 games in 1972, including the Sugar Bowl.

1972- Abe Lemons, with tongue-in-cheek remarks, has a solution to cheating in recruiting. He says, “Give ever …… coach the same amount of money to spend on recruiting, and let him keep what’s leftover.”

Switzer added flash, flamboyant rings, and a fur coat to the Sooner Nation during the recruiting process

“Down and Dirty- The Life and & Crimes of Oklahoma football” by Charles Thompsons and Allan Sonnenschein states that Barry Switzer understood the needs of poor but talented black athletes. . As has been proven to be true, the Proposition 48 tests had a cultural bias. He chose to violate NCAA rules that he felt were either archaic or unrealistic by condoning “financial aid” to the players from boosters. An offer to help an athlete was ok, but it had to be done the “right way’. (Whatever that means). Switzers staff also “worked” with the professors of academically challenged athletes to maintain their eligibility for game day.

1972

In 1972 the NCAA made freshmen in football and basketball eligible for varsity competition. 1972 was also the first year of fully integrated football as the last of the Southeastern Conference schools joined the rest of the football world; the racial transformation in college football was complete.

1973

in a special session in August 1973, the NCAA divided its membership into Division One, two, and Three. The school’s most committed to big-time football could now begin to legislate for themselves, period.

Also, in 1973 the NCAA required only that incoming scholarship freshmen earn a 2.0 grade point average in high school courses, whether physics or woodshop. To the casual observer, that 2.0 requirement might have looked rigorous, but in fact, it opened the door to recruiting virtually any athlete the football coach wanted. Suddenly with the new 2.0 standard blue chip, athletes, regardless of their academic preparation, could play a scholarship sport.

Waves of black football players were the beneficiaries of the NCAA’s lower admission standards. Having offered talented athletes with six or 7th-grade reading riding and math skills, the top priority for universities was how to educate them and keep them eligible.

Two answers were to give athletes credits for courses they did not take or passing grades they did not earn.

In the 1970s, the USC athletic department admitted 330 scholastically deficient athletes, mostly football players, independently of the universities admission process and then kept many of them eligible through devices such as credits for phony speech courses.

In Georgia, the athletic department ran its own laboratory in the university’s developmental studies program to keep several football players eligible for a bowl game by receiving credit for grades in advanced classes after felling remedial coursework in the same subjects.

The pattern of academic abuse in the admission and investment of student-athletes at the University of Georgia due to pressures from the athletic department and with the knowledge of the university president was abhorrent. Two high-level administrators were fired, and the presidents resigned.

In the book “Down and Dirty- The Life and & Crimes of Oklahoma football” by Charles Thompsons and Allan Sonnenschein state that coaches at O.U. were able to get away with things . The people in Oklahoma knew of the bad business dealings, illegal recruiting techniques, and womanizing but were never much concerned about any of it as long as the team was winning.

The NCAA was criticized for alleged unfairness in the exercise of its enhanced enforcement authority………. As a result, in 1973, the NCAA adopted recommendations…. “dividing the prosecutorial and investigative roles of the Committee on Infractions.” 1973- Abe Lemons from Oklahoma City University files complaints against OU, suggesting NCAA rule infractions. The Sooner nation was upset, but Lemmons said: “Was I the only one to report them?” “There is no one thing that triggers an investigation. It’s a series of things over a series of years.”

Eventually, all this fraud was exposed, and the unethical practices transcended to a national collegiate scandal. The phony summer school credits at Georgia and the USC mess were exposed on May 19, 1980, by Sports Illustrated. A student-athlete hoax scammed America. Academic chicanery was exposed.

Scandal reform started with the NCAA passing Proposition 48 in 1986, which, in effect, restored higher academic scores to qualify for a scholarship. To receive a scholarship and be eligible, a high school recruit had to have a 2.0-grade point average in 11 core course high school courses as well as a score of at least 700 on the scholastic aptitude test.

Bogus credits to keep athletes eligible is finally challenged.

There is no right or wrong answer. No matter the new NCAA ruling, some groups will be punished. Proposition 48 created a whole new collection of problems.

When Proposition 48 ruling was enforced, college football was an integrated world, and charges of racial discrimination followed Prop. 48. African American athletes with poor academic backgrounds period they were disproportionately affected by the tougher rules. Prominent black individuals such as Jesse Jackson accused the NCAA of racism in approving Proposition 48.

The issue was not the core curriculum but the SAT, which had long been challenged for its cultural bias. Joe Paterno said that Proposition 48 was not a race problem. He said the problem was that American culture told black athletes who bounced balls, run fast, and catch touchdown passes were more important than academics.

Collegiate sports history says always follow the money trail to find the motivator for a collegiate administration’s athletic decisions. The harsh reality is the demands of the marketplace are the number 1 priority, and making money will always undermine efforts for academic reform.

1975- UPI breaks with a story that Texas athletes were receiving payment for work not done with the state senate. The NCAA, a UT special committee, and the SWC cleared Texas of any wrongdoing.

1976- the College of Football Association is formed.

Al Eschbach, columnist for the Oklahoma journal accused Texas of being just as guilty as the Sooners of giving excessive numbers of tickets to players for scalping. OU distributed 1, 155 tickets to the players for the OU-Texas game. Royal did his research and stated the Texas players had either received or paid for a standard allotment of 365 tickets. The matter was dropped after this revelation.

1977- John Nelson, who played for OCU basketball in the early ’70s, says “I received special offers nearly everywhere. One place offered him a new car each year”, and another University said they would pay him $100 for every game he started. “Lemons says, “You try to be straight, run a clean program, and somebody down the road is cheating, trying to put you out of business, but if you yell, you’re the one who is scorned. ”

1978- The United States House of Representatives “held hearings to investigate the alleged unfairness of the NCAA’s enforcement processes. New rules were adopted designed to address criticisms made during the hearings. Concerns were abated, but the NCAA’s enforcement processes continued to be the source of substantial criticism through the 1970s and 1980s”.

The gaps began at the 1978 NCAA convention in Atlanta, where a bitter, yearslong fight between the haves and have-nots ended with the richest schools getting their way, dividing the sport of Division I football into two distinct bodies: I-A and I-AA (now known as FBS and FCS, respectively). Two years prior, the have-nots in the new I-AA had seethed that the split would be a “slap in the face.” The haves of the new I-A bristled at the thought of their “super” division eventually spending limitless resources on an amateur sport and thus again splitting. Division I has since become inflated, and more than doubled in size since ’78. In the past ten years, the FBS has grown by 10 teams.

#3 1980’s SWC Recruiting Violations run rampant.

-

6 of the 9 conference schools were slapped with NCAA probations. Texas received two-year probation handed down in 1987 that was reduced to one year for good behavior. Texas was guilty of small offenses such as handing out $80 or less, selling complimentary tickets and letting players use coaches’ cars for short campus trips.

-

SMU got the death penalty, and Governor Bill Clements was implicated.

-

TCU’s violations were almost as bad as SMU’s. In 1985 Wacker kicked off the team 7 players for receiving illegal payments. TCU still received one of the stiffest punishments from the NCAA.

-

Texas A & M received two-year probation for 25 rules violations.

-

Houston received a two-year penalty.

-

Texas Tech got slapped around by the NCAA for minor infractions.

The Power of Oil money led to the demise of the SWC

Comments below are from Journalist Sally Jenkins

The cheating that ran through the Southwest Conference in the 1970s and early ’80s was masterminded by some of the state’s richest and most powerful men. The payoffs and recruiting scams began as an attempt to correct a disparity in the conference that dates way back to 1923. In May of that year, oil was discovered in a west-Texas grape field that belonged to the University of Texas system. The oil and natural gas royalties from that find were placed into an existing account called the Permanent University Fund. The fund is now worth more than $3.7 billion. The state legislature decreed that two-thirds of the annual interest go to the University of Texas, and one third to its next of kin, Texas A&M. None of the other schools in the conference receive so much as a dime from the fund.

All that money for two-state schools created a glaring imbalance of resources among the Texas-based schools in the SWC, and that was gradually reflected on the football field. A&M and Texas either won or shared the league title 18 times from 1940 to ’70. By law, the oil riches belonged to the big two, but as the ’70s approached, Longhorn and Aggie rivals decided that they were loath to let them have all the football riches too. TCU and SMU were powers in the ’30s and ’40s, and their alumni—many of them oilmen riding the petroleum boom—wanted their gridiron glory back.

In 1967 William Clements, a successful oilman and SMU trustee, who would twice be elected governor of Texas, became chairman of the board of governors of SMU. Clements and his fellow Dallas businessmen on the board didn’t like to lose to anybody—not if money could prevent it. From 1970 to ’86, SMU’s endowment jumped from $26.7 million to $282.1 million, and the Mustangs climbed to national football prominence, an ascension that culminated in a record of 41-5-1 from 1981 to ’84, thanks to players like Craig James and Eric Dickerson. It was during this era of football success that payoffs to Mustang athletes and recruits became a virulent disease.

Wealthy SMU alumni, not content with having ruined their own program, proceeded to spend their time and money trying to get the other SWC schools in trouble: A fund was reportedly devoted to investigating rivals and turning them in, and by the end of the ’80s, TCU, Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech and Houston—which hadn’t even joined the league until ’76—had all been punished to varying degrees by the NCAA. Only Arkansas, Baylor, and Rice emerged unscathed.

By the mid-1980s the conference was so tainted that homebred football talent, considered to be among the best in the country, began fleeing to other states, an exodus that has not stopped. In 1986 the state of Texas had 12 recruits ranked among the top 100 nationally, and seven of them left the state to play their college ball.

In the 1980’s “University presidents increasingly found themselves caught between the pressures applied by influential members of boards of trustees and alumni, who often demanded winning athletic programs, and faculty and educators, who feared the rising commercialization of athletics and its impact on academic values. Many presidents were determined to take an active, collective role in the NCAA’s governance, so they formed the influential Presidents Commission in response to these pressures”.

1982 the Longhorns are put on NCAA probation for a ticket-scalping infraction involving wide receiver Johnny “Lam” Jones.

1984A– “The University President’s Commission began to assert its authority and called a special convention in June of 1985. This quick assertion of power by the President of the universities led one sportswriter to conclude that ‘There is no doubt who is running college sports. It’s the college presidents.”‘ “Over time, however, the presidents were gaining a better understanding of the workings of the NCAA, and they were beginning to take far more interest in the actual governance of intercollegiate athletics.

1984B– Starting middle linebacker Tony Edwards was arrested long after curfew and charged with assaulting a police officer. Akers said that Edward would be able to continue to play because he “was innocent until proven guilty. This was a bad decision by Akers because it implied to the team members that they would not be disciplined if they broke team rules. Edwards played against Baylor and the #6 Horns lost 24-10, and the Horns followed that loss with a Freedom Bowl 55-17 to Iowa. There are lessons to be learned here about the importance of discipline in winning.

In 1986 the NCAA went all out in their crackdown on steroids. Bosworth tested positive and had to sit-out the Orange Bowl.

1987– Texas was put on probation for the 3rd time- but the first time with sanctions. 38 rules violation. Only one was serious, and that was small cash payments and benefits give to Tony Degrate by a longtime family friend, who was also a Texas season ticket holder. In landmark legislation in 1987, the NCAA banned boosters from the recruiting process altogether — they previously had been allowed to call prospects .- Coaches no longer babysit committed prospects all the way to signing day. Instead, they had to adhere to strict limitations regarding when and how they contacted recruits. That led to ever more creative interpretations of the rules. While Banowsky served as the chief compliance officer of the Big 12, this case crossed his desk. “I’ve had coaches go so far as to rent a limo and drive it up in front of a recruit’s house, call the recruit on the phone from the limo and have a telephone conversation with the recruit while the recruit is either in the house or on the front porch of the house and think that it was acceptable because they technically weren’t having a face-to-face meeting,” Banowsky said. “They were simply talking on the phone.”

A search of news clippings from the period reveals that the coach in question was Colorado’s Rick Neuheisel, who was accused of more than 50 NCAA violations — many involving improper recruiting contacts — while in Boulder. Neuheisel, now the head coach at UCLA, is the owner of a law degree from USC, and he argued that he had not violated the rule in that case. While that argument might have worked in a court of law, the NCAA does not always offer due process to the accused.

1988- In December 1988 O.U. was put on suspension by the NCAA for three years. The infractions included :

1) An assistant coach had promised a recruit that he would be “taken care of” if he enrolled at O.U.

2) A booster had provided a recruit with an automobile at no cost.

3) An assistant coach gave a prospective recruit a $1000 to induce him to come to O.U.

4) Players on the football team were given cash for their complimentary tickets to games.

5) Free airline tickets were provided to players and recruits.

6) Switzer had supplimented the salaries of his coacher and paid for rental cars for students out of his personal checking account.

7) Transportation, entertainment, and inducements were provided to prospective players.

The NCAA penalties included no televised games and bowl games for three years.

1989A -Texas sophomore Alan Luther’s’ jeep police find a syringe and a small vial of liquid labeled “epitestosterone.” Alan is released but charged with possession of a controlled substance. Dodds ordered one of the most extensive, expensive drug-testing programs in college athletics. The players were all passing the test. In the spring of 1989, the Austin American-Statesman challenged the reports of football players passing the drug test, reporting that as many as 25 Texas football players had used steroids after 1986 and that some players continued to use them during the 1989 season. The substance is used as a masking agent for a drug test.

Doctor William Taylor specializing in anabolic steroids, says an athlete can inject epitestosterone one hour before a drug test and receive a negative result for steroid use.

Jeff Leiding, who played for Coach Akers said he witnessed Longhorn teammates, primarily linemen abusing steroids.

1989B– Senior deep snapper Tal Elliott unexpectedly quits the team. The Austin police on a sting operation seized betting slips with Tal’s name, but the investigation found no other Longhorn names on the betting slips. 3 months later the Austin American Statemen breaks with the story that Tal was the team’s bookie for gambling on professional and college games. Players confirmed that Elliott took wagers from them for various sporting events. A student manager said they “use to come in the locker room with money saying I’ve got to pay off some debts.” One player said, “Tal was right next to my locker. I won’t say specific names, but if you want to get to the nitty-gritty of it, pretty much everybody bet with Tal.” The wagers varied between $2 to $100.

Once again, the Texas Athletic Department investigated with Longhorn great Knox Nunnally leading the probe. The case was finally closed with no NCAA probation for the Horns.

#4 1990’s REGULATING INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS

1991- Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court Warren E. Burger issued a report suggesting new procedures for infractions for the investigation process. The purpose of the review was to “make sure that the process is handled most effectively and that fair procedures are guaranteed, and that penalties are appropriate and consistent.”

1993

UT Faculty Senate approved a “no pass, no play” measure. If passed, this would jeopardize the 1993 basketball players and many football eligibilities. The premise followed by the faculty – “athletes are students first.” The NCAA already had a grade requirement for student-athletes, but the requirements are weak compared to the pending UT measures. This concerned many that complying with the new stricter standards would hurt the revenue stream generated by athletics.

1994

The University president’s involvement with the NCAA had grown to the extent that they had changed the very governance structure of the NCAA, with the addition of an Executive Committee and a Board of Directors for the various divisions, both of which are made up of presidents or chief executive officers.

1996- After 80 Years, The SWC Is Dissolved.

Backstabbing, cheating, and open pocketbooks, starting in the ’80s, reached its zenith in the 1990s and destroyed the SWC. There were also other factors responsible for the demise of the SWC:

-

Arkansas’s joining the Southeastern Conference;

-

Private schools no longer able to compete financially with state schools;

-

too many Division I teams in one state to support a strong fan base for all Texas Universities;

-

the SWC was too regional in scope for national exposure;

-

The Cotton Bowl contractual obligation to feature the SWC winner against another ranked team became an anchor around the Bowl committee’s neck. At best, the play of the SWC teams was mediocre.

“As the role of television and the revenue it brings to intercollegiate athletics had grown in magnitude, the desire for an increasing share of those dollars had become intense. In time, however, a group of robust intercollegiate football programs was determined to challenge the NCAA’s handling of the televising of games involving their schools. In NCAA v. Board of Regents, the United States Supreme Court held that the NCAA had violated antitrust laws. This provided an opening for those schools and the bowls that would ultimately court them to reap the revenues from their football games’ televising directly. This shift has effectively created a new football division called the College Football Association, which is made up of the football powerhouses in Division 1. Because these schools have funnel more television revenues in their direction, which has led to increases in other forms of income, they have gained access to resources that have unbalanced the playing field in football and other sports. ”

#5 2000s Infraction transitioning

2001

Sometimes, a coach can use a new rule to his advantage. Two years after the NCAA allowed Division I athletes to get jobs, first-year Memphis basketball coach John Calipari, who inherited a program with a zero graduation rate, asked executives at local giant FedEx if they would provide paid summer internships for some of his players. Those internships gave Calipari an answer to the toughest question he encountered on the recruiting trail. “I have to enter a house with a zero percent graduation rate and promise parents that will change,” Calipari told The New York Times in 2001. “FedEx lets me show them their kids will get real work experience.” According to a December Forbes story, 25 Memphis basketball players have taken the internship.

The NCAA, under Syracuse Chancellor Kenneth Shaw, was determined to stop the “ leech and parasite” recruiters. Shaw said we have to reach a consensus to balance sports and the academic mission. I don’t think basketball ever eradicated illegal recruiting. Following the money trail and you will know why.

2005

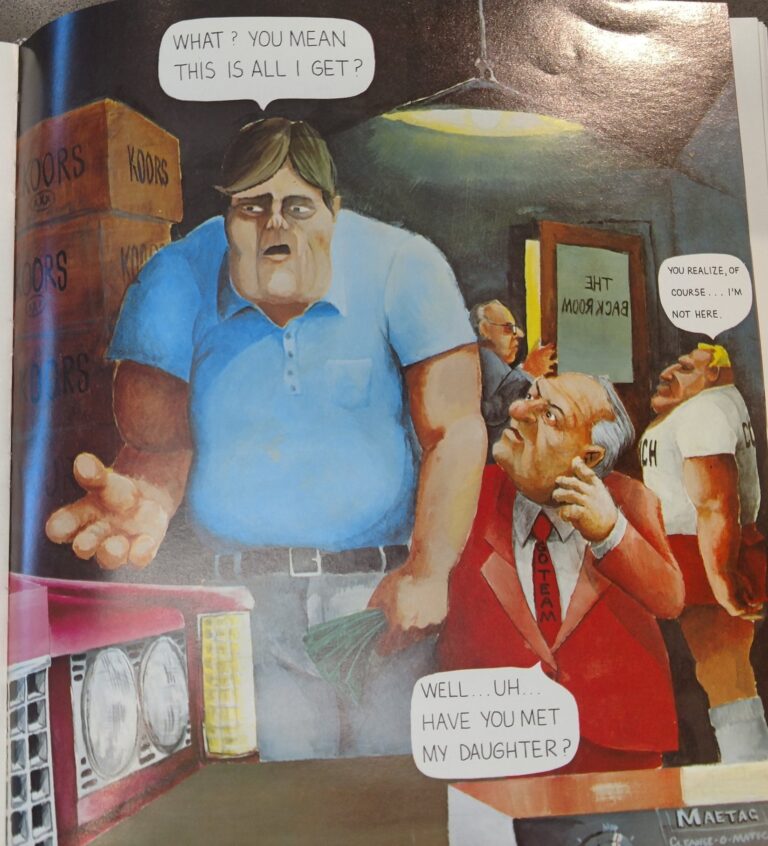

Oregon Ducks designed custom comic books starring each recruit as the hero who leads the Ducks to a national title. Because NCAA rules at the time only allowed programs to send letter-sized, black-and-white pages to recruits, Coach Gilmore sent each prospect one page a week. After a few months, the recruit had the full comic book. And when that recruit came to Eugene for an official visit, he would find the bound, full-color book sitting on a table, possibly alongside a fake Sports Illustrated cover — attached to a real copy of the magazine — featuring the prospect wearing an Oregon uniform and holding the Heisman Trophy.

Recruits loved the books, and they helped the Ducks land several stars. For example, Jonathan Stewart didn’t lead the Ducks to a national title the way he did in Snoop: A Hero Is Born, but he did become the school’s second-leading rusher in just three seasons. Before they could immortalize the class of 2006 in graphic-novel form, Gilmore and his team received the ultimate backhanded compliment — the NCAA banned the books.

New academic standards were established that are ripe for fraud and deception. A 50% graduation rate over a 5 year period was mandated for each university. Schools that don’t maintain 925 on a scale of 1000 are subject to scholarship losses. The president of the NCAA, Myles Brand, stated: “ (The NCAA) is holding schools and individuals for the academic success of their student-athletes.” “The messages are clear: Recruit student-athletes who are capable of doing college-level work. Help them meet the standards for progress toward a degree and work with them and keep them enrolled so that the opportunity for quality education becomes a reality.”

Based on the 2003 – 2004 school year, 410 Division I teams risked penalties, and 328 Division I schools have one team facing sanctions.

The Big 12 needs more classroom participation from their student-athletes ranking 8th among the 11 conferences in Division I.

All 9 of the Longhorn women’s sports exceeded the 925 mark with sports receiving a perfect score.

2007 -NCAA banned texting in 2007.

0.05.2012 | Football Bill Little commentary: New folks

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

The massive changes in the college football landscape began in the late 1980s and early 1990s when Penn State announced its intention to join the Big 10 Conference. Soon afterward, Arkansas declared it was moving from the Southwest Conference to the SEC. The 1980s had been a traumatic time for the Southwest Conference.

But as the 1990s proceeded, the large shadow of the television industry began to influence decisions. The Big 8 Conference, whose schools were linked geographically in the Midwest, had only seven percent of America’s TV sets. The Big 10 had over 30 percent and the SEC 23 percent. Even though Texas teams brought major television markets in Dallas and Houston, the SWC had only seven percent coverage itself.

#6 Judging intangibles is where Coaches make the most recruiting mistakes – The Good Egg

Recruiting Student-Athletes By The Early ’70s Morphed Into A Research Laden Process Requiring Full Dossiers On Each Potential Student-Athlete, But Recruiting Errors Were Still Made.

-

Coach Lemmons says that intangibles are how the prospect handles himself- charisma, mannerisms, excitement level, and the way he shoots the ball.

-

Abe Lemons said that farmers could hold up an egg to the light and see if it is a good egg. Unfortunately, recruits cannot be handled that way “to see what is inside ’em.” Abe Lemon once said, “doctors bury their mistakes, but mine (recruiting) are still on scholarship.” Coach Lemon concedes that “it’s the worst part of coaching.” The annual search for high school talent is one of the most pressure-filled parts of college sports. Recruiters can’t read the player’s mindset, so they decide based on the high school athletes’ past performance, agility, and quickness.

-

Some athletes who did not have to work hard in high school are not willing to pay the price of hard work. Others are too overconfident that they do not feel the need for sufficient effort.

-

Others have a great attitude but play poorly in pressured games.

-

Many great athletes lose interest in the sport for many reasons: homesickness, a girlfriend at home, or just sports burn-out. In 1978 Booger Brooks from Andrews Texas signed by Coach Freddie Akers, but he packed up his car and went home before he ever took a snap in a game. His heart was not in football. He loved the rodeo and wanted to be a welder. Akers tried unsuccessfully to talk Brooks out of leaving U.T., but he left the game with the comment, “People were just a lot more serious about football than I was. To me, it was always just a game”.

-

Others leave the program because of timing issues. Mike Presley was a great athlete who could have started for many other football programs, but Mike had to compete against Marty Akins. Mike never got the starting job, so he left the Longhorn program in his senior year. While Priest Holmes did graduate from Texas, he was in the same position as Mike Presley. After suffering an injury, Priest was Heisman trophy winner Ricky Williams back-up.

-

However, the primary intangible that recruiters cannot judge is a player’s ability to adjust from home life to college life. Many athletes are unable to adjust to all the freedoms and responsibilities of college. Immaturity, poor role models, bad study habits, lack of discipline, little foresight, inspirational and motivational deficiencies, and alcohol abuse result in a loss of free education.

#7 RECRUITING STORIES

-

-

Author and former Longhorn football player from the 1940’s R.E. Peppy Blount are still relevant in 2019. “How does one quell the recruiting abuses of the paunchy, overzealous alumnus, whose fool brains, understanding — and ability in most instances— never got any higher than their stomachs”?

1) In the early ’30s, Tex Robertson won the national championship as a swimmer at the Junior College level. He received a scholarship to USC, then transferred to the University of Michigan and was listed as a freshman again. The NCAA finally caught up with Tex, and he was ruled ineligible to swim for Michigan during the 1936 season.

2)When Tex Robertson accepted the head swimming job at Texas in 1935, he had no scholarships to offer swimming athletes. But he still provided scholarships to some of the best swimmers. “Tex’s solution was to pay for as much of the Longhorn swimmers’ scholarships as he could with his own money. Admirable but not allowed under NCAA rules. Coach Reese, the present Coach of the Longhorn swimmers, said Tex’s help was “morally fine, ethically fine but NCAA’-L.Y., he was a dead man.” Fortunately, the NCAA in the ’30s was still not enforcing many of the institution’s rules, and Coach Robertson was not punished.

3) Joey Aboussie was an All American in high school, and many universities were “bidding” for his service under the table, but he chose Texas with no bribes offered. Joey says most of the bribing came from the alumni, not the coaches. Like many other recruits, Joey said he was not prepared for the pressure put on him to sign.

4)In the early ’60s, Ernie Koy was heavily recruited by universities across the nation. One recruiter came to his house and volunteered to help him slop the hogs at sundown on his father’s place, hoping that this work would convince Ernie of their sincerity to “help” him. Ernie says, “I never met a nicer bunch of gentlemen.” Ernie signed his letter of intent with Texas and learned very quickly that the honeymoon was over. The recruiter who wanted to tuck him in at night and loved his parents changed dramatically. Ernie got no more sweet talk from the coaches. It was time to learn and earn.

5) In 1960, Duke Carlisle told a story in his book about the harshness of rejecting a recruiter’s courtship. Duke decided to cancel his Baylor trip to attend Coach Royal’s spring game. When he told the Baylor coach he was canceling his visit, the Coach was upset and said: “Well then, why did you schedule it?” He then said to Duke, “He (Duke) might want to be careful with his flippant attitude.” After this incident, Duke said: “the fun and glamour had fast gone out of my recruiting experience.”

6) Coach Todd Dodge a 1982 recruit says to his high school football players in 2018, “back in 1980 and 81 when I was getting recruited the recruiting process started around January 1 and it lasted about one month,” Dodge said. “There were no games that you went to; there were no camps; there were no junior days. You found out, basically, from your coach when the season was over. ‘Oh, by the way, these guys like you”. He (the high school head coach) probably already set up your visits for you, and here’s your four, five visits. So it was only about a one month process.”

Todd Dodge says, “One of the things we try to tell our (high school) players is don’t let anybody take your joy away during the (recruiting) process.”

7) Billy Dale wishes he had listened to Todd Dodge and Duke Carlisle. As a 17-year-old boy in 1967, It sounded like fun to visit a campus, all expenses paid, but it was not. He always respected authority, and coaches were the center of his authoritarian universe. Informing one coach from an SWC university that he would be a Longhorn was his first brush with the mean spirited side of recruiting. The day after he publicly announced his decision to attend Texas, the coach, whose courtship was rejected, called him at 7:00 A.M. on a school day. By respecting authority, Billy listened to the Coach, but he soon realized that this coach’s soft-sell approach had morphed into a hard-sell approach. Billy got upset when the coach said: “you will never play at U.T..” His father finally stepped in, yanked the phone from him, and said to the coach, “the boy has made his mind up, and he is going to be a Longhorn.”

Scalping Tickets and other Infractions

Players were given two complimentary tickets and the option to purchase four more, all on the 50-yard line. Most players opted for the six tickets to sell the tickets to corporations and wealthy alumni. Unfortunately, scalping tickets were banned by the SWC in the late ’40s, which resulted in objections from some prominent members at the university level. Clemson’s Athletic Director reasoned that if it was ok for the student body to scalp their tickets, it should be alright if athletes yo do the same. Coach Bear Bryant said when he was at college, “scalping tickets paid for toothpaste and shaving cream” and various other necessities. For many of the players from low-income families, this extra money helped them with incidentals and even dating. From my recruiting experience in the late ’60s, I know scalping tickets were prevalent, so the 1940 SWC ruling against scalping must not have been enforced. In 1976 O.U. Players made a lot more money than Texas players off of ticket sales. Texas players in 1976 bought 365 tickets while O.U. players bought 1155. In the book Down and Dirty- The Life and Crimes of Oklahoma football by Charles Thompson and Allan Sonnenschein, Charles admits that in 1989 “ there was more demand for O.U. tickets than seats available and “the players had plenty of tickets, and that was the only currency we needed.”

Longhorn infractions

Winning games begins with signing great recruits. A coach can hardly overcome a lack of talent by implementing a superior recruiting technique because competitors immediately mimic any recruiting success story. Universities that cheat most often do so because they have some inherent recruiting disadvantages (location, prestige, better heritage, and …). So they justify cheating as necessary to add value, making their University look equal in the recruit’s eyes.

Coach Akers inherited a program when The SWC was losing the battle to remain relevant and competitive with other conferences. In Fact, In 1980, 1986, 1988, and 1989 there were no SWC Teams in the final top 10. The great Texas high school football athletes left the “boring” SWC for more “exciting” football venues. Many SWC teams resorted to desperate means to survive – including illegal recruiting, dirty money, and predatory tactics. Only Rice, Baylor, and Arkansas escaped the eyes of the NCAA in the ’80s. The going rate for recruits was about $300 per month. That means that a team could get about 15 top players for the price of an assistant coach’s salary. There are reports of superstar recruits getting six figures, but these offers are rare.

After an 18-month investigation, U.T. is accused of violating 19 NCAA rules from 1980 – 1986. Texas received some minor sanctions for giving players small loans of $10- $50, loaning cars to players, and selling complimentary tickets. Akers said, “These violations are an accumulation of small things over a long period that could happen almost anywhere you have a major program.” Twenty-five players lose some or all of their complimentary tickets for scalping.

Stealing a lollipop is not as significant as stealing a car, and in this analogy, Texas took a lollipop and S.M.U. stole the car. S.M.U. chose deceit over compliance to recruit great athletes and fill their coffers.

Fortunately, for the integrity of college sports, S.M.U. was caught and punished with the “death” penalty. Naturally, there were a lot of Longhorns complaining about how minor the infractions were. Ken Hackemack, the U.T. defensive tackle, said, “I think the NCAA is making the S.W.C. into the scapegoat for violation accusations.

It is ridiculous to punish S.W.C. teams when most other schools are making the same or worse violations. Almost everyone does it. It is hard to avoid. Stephen Llewellyn, another defensive tackle said, “If they penalize us for a coach lending $10 for a guy to go home for his mother’s funeral or lending a car to go across campus, then in the light of violations like S.M.U.’s, ours are minor and ridiculous.” They (NCAA) are making a big deal out of nothing. Now, if they uncover something like boosters giving significant gifts, well, then we should be punished.” Jeff Ward, the U.T. kicker, said, “The NCAA is ridiculous. They are naive, and they seem to have their priorities in the wrong places. They are so understaffed that they can’t catch the real violations. I guess they have just decided to camp out in Texas and flash their badges here for a while. They should have something better to do. ” However, the U.T. President William Cunningham disagreed with the players on the team. He said (The violations) may be perceived by many people as relatively minor, but the University takes any violations of rules seriously.”

Four weeks earlier, SMU received the “death penalty” from the NCAA. SMU in the 80’s chose deceit over compliance to recruiting great athletes to win games and fill their coffers. Fortunately, for the integrity of college sports, they were caught. The NCAA rightfully punished SMU with the death penalty.

Bryan Millard labels the Texas-SMU game as competition “between a couple of jailbirds.”

1) 1987, Eric Metcalf violates an NCAA rule. He receives room and board at Jester Center during the summer, but he does not attend school. The punishment is a one-game suspension for Eric. He misses the BYU game, and Texas loses 47-6.

2) In 1995 Texas Wins The SWC Championship With A Scholarship Player Who Has No College Eligibility. Ron McKelvey (Ron Weaver) Plays In all 11 Games At Texas. His Mother And Father don’t even know He Is On The Texas Team. Federal Prosecutors Charge Ron With “Fraudulent Misrepresentation” And Misuse Of a Social Security Number. The Result- No NCAA Infraction for Texas And Ron reimburses Texas $5000 For The Cost Of The Scholarship.

3) Texas gets probation without sanctions for buying Marcus Dupree’s new boots.

Unfortunately, the need for winning, power, and money still lead to infractions in college sports. Hence, with all its flaws, the NCAA is still necessary to both investigate and enforce sanctions. Unfortunately, in many cases, probation builds a football program instead of acting as a deterrent. 8 of 13 of the colleges with the most infractions – OU, Auburn, Florida State, Texas A & M, Georgia, Wisconsin, Arizona State, and West Virginia- have, in most cases, not been hurt by illegal recruiting.

It is not the purpose of this website to overload the reader with statistics to prove a point. If you are interested in this subject, visit the OU season record website and compare the Sooner’s won-loss record after probation vs. SMU’s record after the death penalty. You will be surprised by the data.

The recruiting Infraction story has Not Ended- to be continued in the present and future.

Be careful what you ask for and remember the Faust·ian | \ ˈfau̇-stē-ən , ˈfȯ- \ parable.

Definition of Faustian –made or done for present gain without regard for future cost or consequences a Faustian bargain

Greed Comes for College Football: Knight Commission Recommends the FBS Leave the N.C.A.A.

Mark Schipper

Dec 11, 2020

-

Jan 17, 2021

NCAA Delays Vote on New Compensation and Transfer Rules, but Revolution Remains a Real Threat

By Mark Schipper

The NCAA has built a reputation as a steadfastly conservative, even reactionary, organization after decades of swiftly and deftly shooting to bits any proposal that threatened to modify their model of amateurism, which they had well established in the early decades of the twentieth century.

This pay for play concept has been roundly rejected by the NCAA and described for decades as a non-starter as a reform mandate. It is an issue they consider untouchable as an amateur organization and one that would signal the end of their oversight of collegiate athletics. Even their new reform legislation is explicit about athletes not being employees of any single school, or being compensated directly for their athletic efforts. All of their proposed compensation allowances are tied to individual name recognition and notoriety, and not as athlete-representatives of a specific university.

Regarding the potential anti-trust issues, the NCAA recently received a letter from Mark Delrahim, the antitrust division leader of the U.S. Department of Justice, warning that a program overly restrictive to an athlete’s rights to compete in an open marketplace could trigger antitrust action from the government.

Even as the NCAA attempts to move forward, they are finding their organization is stuck in the past. And because they waited so long to acknowledge the problems with their model of amateurism, their piecemeal approach to fixing them has come so late in the game they are in danger of being swallowed up by a far more revolutionary model mandated out of the nation’s capital by ambitious legislators.

Whether or not the NCAA survives this round, and they will, is not the important thing. These battles over the future of college athletics are only beginning and what comes out the other end in the next decade is at the moment a bad bet on any square. The NCAA might get its chaos, after all.