RED Candle Tradition

1941- The Longhorn Red Candle Tradition starts.

Since the Horns had not defeated A & M at Kyle field since 1920 Some UT fans implored Mrs. Augusta Hipple, a fortune teller, to help break the jinxes. She instructs the Longhorn fans to burn red candles, and the Longhorns would win. In 1941 Texas won 23-0 at Kyle Field.

After its success in 1941, the red candle hex was used sporadically when the Longhorns faced highly-ranked opponents. In 1950 the red candle tradition helped Texas defeat the No. 1 Southern Methodist University (SMU) Mustangs 23-20.

In 1953 The Daily Texan called on all fans to light their red candles to defeat a Baylor team that was unbeaten and battling for a national championship. The #3 Baylor team fans countered the hex by lighting up every green candle in Waco. Time magazine said this tradition was the “most potent whammy in Texas traditions, and nothing to lightly invoked…” Texas won 21-20 .

In 1955 The red candles came out for the Texas A & M. The Horns were heavy underdogs. The Hex was put on the Aggies, and the Hook’em Horns hand signal was introduced at the Friday night pep rally.

In 1963 the Red Candle tradition led to another victory over a great Baylor team. But the social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s changed students’ attitudes toward long-established university traditions. Many were abandoned and forgotten, including the red candle hex.

In the 1980’s, the Red Candle tradition evolved into more of a hex-breaking Chinese legend.

THE 1986 MUSTANG HEX RALLY.

With the Longhorn Band’s arrival and the Main Mall packed with students, the inaugural Hex Rally began at 11:30 p.m. with songs, yells, speeches, and a retelling on the origins of the tradition. The Aggies were “hexed” at midnight as thousands of students raised red candles and sang “The Eyes of Texas.”

2001- Mack Brown attends a Hex Rally

In the drizzle on the Main Mall, Mack Brown experienced his first Hex rally. In attendance were 1000 fans, the Showband of the Southwest, Tour de France winner Lance Armstrong, and a modern dance group.

Visit the Texas Exes UT History Central Web site for more fun facts about the university’s history.

Many years later, Mrs. Hipple shared her story about the Red Candle tradition. She told the students who came to see her in 1941 that “red means alert and that they needed something to show the team they were behind them.” She concluded her interview by saying, “the boys were struggling so; they only needed something to relax the child that is within us all.”

In Bill Little’s book Texas Longhorn Stadium Stories, “the message of the red candles wasn’t magic; it wasn’t an ancient Chinese hex breaker. It was the simple truth that applies to whatever in life you choose to do. “There is a “force” out there when people band together in a common goal, and the strongest force of all is the bright, burning will that lives inside of you.”

How Madame Hipple Became Austin’s Greatest Psychic

With a stroke of luck, she went from cleaning classrooms to telling fortunes.

By Rosie Ninesling

AS-72-79784, Austin American-Statesman Photographic Morgue (AR.2014.039). Austin History Center,

Austin Public Library, Texas.

Augusta Hipple

A chance encounter in 1941 turned Augusta Hipple into Madame Hipple, Austin’s resident clairvoyant. While working as a janitor at the University of Texas, she was approached by a group of students with a problem: The football team had a crucial game against A&M, and they were seeking supernatural assistance. “A fortune teller?” she asked. “I am one.”

Without thinking, Madame Hipple conjured up an impromptu hex that consisted of a red candle left in a window overnight. When the Longhorns won 23-0, the cleaning lady was launched into campus-wide fame.

That week, she traded her work apron for kaftans and tied her cherry-red hair up in scarves. Using the money she began to make from her college-aged clients, she was able to leave her rundown apartment for a home in West Campus. With hearts, spades, diamonds, and clubs cut into the picket fence, she aptly named it “The House of Cards” and conducted readings from a closet-sized space at the front of her home.

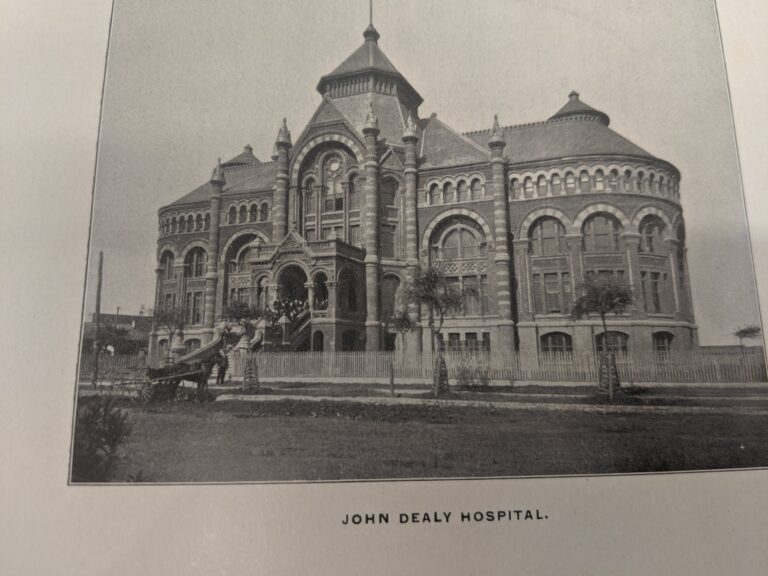

Decades passed, and the problems varied: Sorority girls wanted to know when they were getting married. The boys questioned life after graduation. And when Charles Whitman came to see her just weeks before the tragic UT Tower shooting in 1966, she allegedly advised him to “quit playing with his toys and grow up.” A permanent fixture on West 29th Street, she was a resource for anyone seeking direction up until her retirement in the mid-’90s.

Could there be truth in the magic Madame Hipple harnessed? Perhaps a secret is best kept secret. When her son sold the house in 2004 to Adam and Maggie Stephens, the new homeowners made sure to ask about his mother’s powers. He responded with a smirk. “Let’s put it this way,” he said. “My mother was always a very good businesswoman.”