Scholarship housing since 1935- pending

The Three Athletic Dorms in the history of Longhorn sports may be in trouble with NIL money available for athletes to move to more posh accommodations.

Moore-Hill Hall

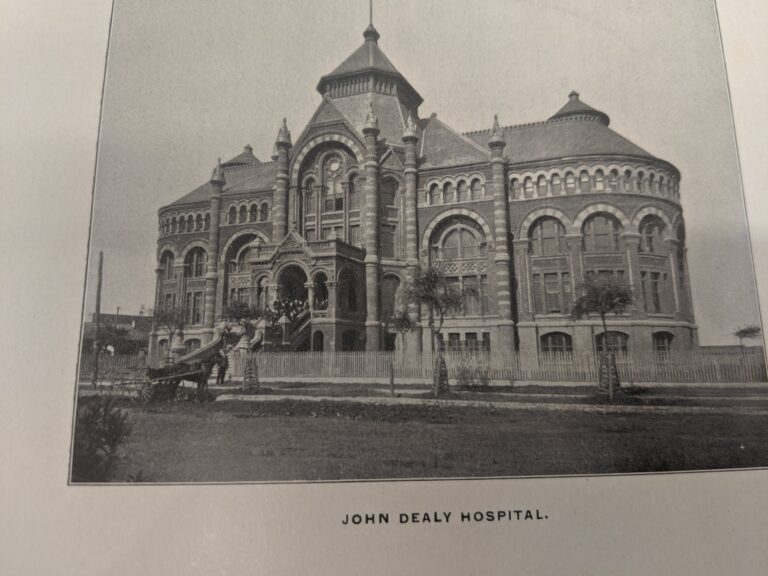

Hill Hall is named for Dr. Homer Barksdale Hill of Austin who volunteered to treat UT athletes from 1893 until his death on July 18, 1923.

Beginning in 1939, the university housed its athletes in Hill Hall. The five-story building (including the basement) is of Spanish Renaissance style with a red roof and tan bricks. The Public Works Administration provided a grant of $46,636 and a loan of $57,000 to cover the cost of construction. When originally opened, the building housed 84 men.

As its athletic programs grew, the university added Moore Hall in 1955, just south of Hill Hall and connected to it, to house additional male athletes. Now known as Moore-Hill Residence Hall, it is open to the entire student body. The hall went coed in 2005.

1935-1938

Coach Chevigny was an innovator and proactive thinker, if not a good coach. He bought a field cover to protect the grass on the football field and started filming games for study purposes. 1935-1938 Under Chevigny, Texas had its first ‘training table” and athletic dorm with a “dorm mother” by the name of “Ma Griffith””

Ms. Griffith required prayers before each meal. Tom Stolhandske said in the early mid-50, “she walked around, and if she saw anybody acting up,…., she’d scoot behind them, grab them by the hair, pull their head back, and give them a real lecture.”

I worked in the chow hall in 1962 and believe she was still alive and present. At that time, Ma was mostly a figurehead. The dining room was being run (as I recall) by Ma’s daughter and son-in-law, Jim Blaylock. As I recall, he was the equipment manager in the athletic department. Jim Wilson 1962 said “Ma’s “attacks” with her cane always drew approval from the athletes. Her dining table was outside the door to her apartment. Coaches and other athletic personnel ate with her. Upper-class football players occupied the table next to hers, so there was a lot of uproars when she “disciplined” one of those fellows. Frequently it might be the closest guy, not the one deserving it. “

Julius Whittier remembers the Dining Hall environment.

In the Book “Texas, Our Texas” Julius remembers his first impressions eating in the dining hall during his recruiting trip.

>

“I didn’t have any idea what they were talking about. But the cozy and crowded atmosphere of the Moore hill dining hall was impressive, to say the least, and I found out what family-style dining meant. There I was a rather small offensive lineman aspiring to sit and break bread with the likes of All-Americans and All southwest conference players.As it turned out, family-style dining meant piping hot food served in big bowls… The rule set down by Coach Royal was, ‘take all the food you want, but eat all you take’. Beyond this, the style of eating in the athletic dining hall had no relation to family-style dining.

Dining at the Texas training table is more accurately summed up by Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. Only the strongest survived. Simply getting to the table closest to the door of the kitchen took deft athletic skill and agility. Once at the table, your finer skills of manual dexterity and hand-eye coordination came into play. For the first five minutes at the table, there was more reaching and grabbing for those bowls of food than there was for the last plane out of Saigon in 1975.

\

It was strange for me to be one of only five blacks in the room who were not working in the kitchen. But apparently, because Leon O’Neil was well respected a number of guys came over to where I was sitting and asked my name, welcomed me, and said they hoped I liked Texas.”

TEAM-BUILDING 101: DORM AND DORMER

By Professor Larry Carlson

I had read earlier of Sark’s logic about a lack of literal togetherness perhaps hampering the molding and forging of a tight team that was long on camaraderie and mutual trust. I understood.

At a Houston Touchdown Club meeting back in May, Steve Sarkisian told those of us in attendance that a big improvement in spring ’22, was in team togetherness. He didn’t put it in those exact words but Sark blamed the lack of meeting space at the stadium for a somewhat disjointed squad during his first spring, 2021, at the Forty Acres. Many of the areas with potential for gatherings had been undergoing repairs and refurbishing. And Covid protocol had often prevented or hindered attempts to get teammates and coaches together indoors. Now, in ’22, meeting spaces were plentiful and the Covid rules and dangers had waned. Stoking the coals of togetherness was easier.

Fair enough.

Photo of Coach Sark and the Houston Touchdown Club honoring Tyres Dickson

But the topic made me wonder about the long, slow erosion of the most basic foundation for team bonding. The dorm.

Anybody who ever lived in a college dorm, at least one in the twentieth century, knows dorms were often short on amenities, comfort and privacy but could definitely be long on togetherness and strong on fostering an overall esprit de corps. In my experience, Jackson Hall at Southwest Texas State was filled with laughter and a zany quality of life, what with golf balls being blasted down long hallways amid thunderously loud communal music featuring Led Zeppelin and Grand Funk Railroad. The jolly atmosphere made up for rather spartan living conditions and communal shower/restroom facilities.

But I digress. For several decades, many Longhorn players beyond their first few years in school, have lived in off-campus apartments. I suspect that contemporary athletes consider the “new” trend a major upgrade from dorm life. Since the 1970s, some schools have famously/infamously provided plush living quarters and five-star dining facilities for scholarship athletes. However, UT was never among them, choosing to expose student-athletes to living quarters more in line with what the remainder of the student body works with.

Professor Carlson with Donnie Wigginton and Jay Arnold at the Houston Touchdown Club.

The first description I read about Moore-Hill Hall, home to Longhorn football players while I was growing up in the 1960s, came from Sports Illustrated magazine. In a feature spotlighting All-America halfback James Saxton back in ’61, his dorm room was described as “the size of a pool table.”

Moore-Hill was aptly enough named. For players, getting back there was a hike up a steep hill from Memorial Stadium, not a welcome trek after hard work in any weather.

Longhorn athletes moved into the new Jester Center in 1969, a complex featuring modern/industrial accommodations for UT students in two high-rises (fourteen stories for Jester West, ten for Jester East), sometimes referred to as “the grain elevators.”

Like Texas itself, Jester was big, housing more than three thousand students. It was UT’s largest building project ever and unlike Moore-Hill Hall, was home to both male and female undergrads. And it’s no urban myth that Jester had its own zip code. It did, 78787, until 1986.

Both Moore-Hill and Jester offered, it is safe to say, more camaraderie than do apartments. Twentieth century football players, except for the very few married ones, lived in the dorms until they completed their eligibility.

One player whose UT football days straddled the “old” Moore-Hill and “new” Jester era, pointed out that Longhorn players resided on various floors of Jester, a room assignment policy he considered a hindrance to forging bonds between teammates. By e-mail, he lauded Moore-Hill for what he termed “a warm, team-bulding ambiance.” That same player also noted that the doors at Moore-Hill were sturdy and those at Jester were hollow.

When I texted Turk McDonald out in Midland to ask him about his dorm days, the ’92 All-Southwest Conference center was busy at work. That evening, he texted me that he was “enjoying a cold pop, watching James Brown and Dan Neil beat m&a on LHN” in one of the old rivalry’s mid-’90s matchups.

So I rang him up and briefly interrupted the merriment. Turk reminisced about the old days at Jester and said he thought the accommodations were great.

“It was awesome. You even had a fold-out couch. My Dad spent a couple of nights up there with me.”

He called the team camaraderie resulting from dorm life “a huge deal,” fondly recalling spare time competing with teammates at cards and dominoes. When I asked about today’s trend for universities to provide apartment living as the norm for upperclassmen, McDonald was blunt. “It’s weird to me,” he said.

When I spoke with a Longhorn player from the late ’70s, he expressed sentiments similar to McDonald’s, regarding obvious advantages to team-building by housing student-athletes in dorms, not apartments. And one ‘Horn who played in the early ’70s said while he couldn’t compare anything to an apartment because he never experienced apartment life, he readily harkened back to the bonding built through dorm living. He said eating at the dining hall at the same times every day, walking to and from practices together, going to classes and having group study hall time set aside, all forged connections.

This player who chose to remain anonymous even recalled the old-fashioned, family-style practice of occasionally fighting with a teammate but then making amends and bonding like brothers under the same roof. He mentioned the advantages of learning about teammates’ hometowns and days of growing up, then meeting their parents and siblings when they came to visit for games.

“In my opinion, dorm life was a way to develop strong, lifetime friendships, a team atmosphere on and off the field for a strong bond that continues to this day,” he concluded.

Every former Texas player I spoke with acknowledged the team rewards of dorm life together, even if the rooms weren’t large and the walk back from grueling drills was always a grind. So if Coach Sarkisian wants a simple team-building aid, dorm life together is a proven practice. But I’m certainly not expecting Sark to reverse and revoke the apartment allowance for players.

If anything, it’s more likely in the NIL era, that future prized recruits and high-profile stars will end up with posh penthouse arrangements in million-dollar lofts in some of the dozens of Capitol City skyscrapers.

Maybe those cool digs, with their close proximity to other towers, can rival what was perhaps Jester’s greatest advantage within the “grain elevator” layout. When I asked one player who lived in both Moore-Hill and Jester to name the biggiest “pro” for Jester against cons like noise and notoriously slow elevators, he noted that the new towers boasted one superior feature that trumped whatever the old hall could offer. What was it?

“Watching girls undress in their rooms across the courtyard from our study hall,” came the ready answer.

The Professor of Longhorn College sports History visiting Alabama

TLSN TLSN TLSN TLSN TLSN

Jester Center- 1969-2014

Jester cost $17 million when it opened in 1969, and a comparable hall would cost $300 million to build now, Porter said. So Housing decided to start tackling the updates.

Jester: huge dorm, often disliked for being less nice but perfectly liveable, and home to restaurants, classrooms, a post office, etc.

Towering above neighboring buildings on the south side of UT’s campus, many students joke that the dull, dreary-looking Jester Center looks like a prison.

With a capacity of 3,200 (3,300 with supplemental housing) students, it was the largest residence hall in North America at the time it was built.[1] The building complex, which occupies a full city block, was the largest building in Austin, Texas when built and was the largest building project in University history.[2]

The complex includes two towers: a 14-level residence (Jester West) and a 10-level residence (Jester East). The first four floors in Jester West still have built-in furniture, while the remaining floors and all of Jester East have been completely renovated to offer movable furniture. All rooms boast XL-twin beds. While some rooms have private or connecting baths, most students use community restroom facilities. Each tower also has study rooms, lounges, laundry rooms, and storage areas.[2] From time to time, the study lounges have been converted into “supplemental housing” for students who are not allotted a standard residence hall room.

The residence hall also houses several offices for student services, tutoring, mentoring, academic advising, classrooms, and lecture halls. The center also contains an all-you-can-eat cafeteria called “J2 Dining” (signifying Jester 2nd floor), a Wendy’s, an a la carte dining center known as “Jester City Limits” (an allusion to Austin City Limits), a convenience store named “Jester City Market”, Jesta’ Pizza, Jester Java, which serves Starbucks, a bubble tea shop named “Bliss,” and the Jesta’ Texas Gift Shop, selling UT apparel.[3]

San Jacinto – 2014 to present

San Jacinto Hall sits at the southwest corner of 21st and San Jacinto Street, tucked away from the inner campus’s bustle but still conveniently located near several of its major resources. The hall, built in 2000, accommodates nearly 900 students in rooms with private bathrooms, study lounges on every floor and access to the popular Cypress Bend Cafe. San Jacinto has many community spaces for residents to hang out, promoting a welcoming and social environment.

University of Texas at Austin, San Jacinto Hall

AREA

304,183 sq.ft.

TOTAL COST

$52,400,000

COMPLETION DATE

01/2001

San Jacinto Hall was designed to follow the human scale and character of the original 40-acre campus plan. The new residence hall is configured as two towers rising from a two-story base, which is set into the natural slope of the site. Intended to house freshmen, the facility accommodates 854 students in double rooms with a private bathroom in each. Each floor has social and study lounges.

Accompanying the living areas of the residence hall is 8,800 square feet of community space for the students, which also is used as a conference center for workshops and seminars during summer sessions. It includes a large multipurpose room along with four smaller conference rooms. Two food venues, a convenience store and other student amenities also reside within the facility.

Through the use of similar building materials, design aspects and building massing, San Jacinto Hall is able to form an extension of the campus framework.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

CAPACITY

854

COST PER SQ FT

$172.00

FEATURED IN

2002 Architectural Portfolio