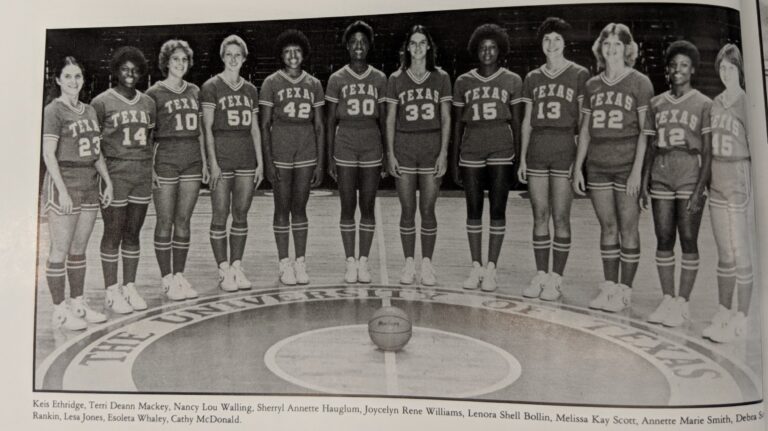

Sherryl Hauglum 1

The lure of NCAA TV exposure and travel subsidies left just three ranked teams sticking with the AIAW and winnowed its 1982 tournament field to 16. As a result, NBC canceled plans to air the championship game between Rutgers and fifth-ranked Texas at the Palestra in Philadelphia. A crowd of 1,789 attended, and Rutgers’ student radio station WRSU-FM provided the only live account.

Although Texas was favored, Rutgers’ Lady Knights had the edge in size and experience, led by senior forward June Olkowski and twins Mary and Patty Coyle, who manned the backcourt. All three starred in Philadelphia’s girls’ Catholic League and were childhood fans of Rutgers Coach Theresa Grentz when she led Immaculata’s Mighty Macs to three AIAW championships from 1972 to 1974.

“The Palestra is a very, very special place in Philadelphia because the Big Five — St. Joe’s, Villanova, Temple, La Salle and Penn — played there, and the girls’ Catholic League championship was played there. It was like a gladiator pit.”

“… We were at the shoot-around the day before when Jody [Conradt] and her team came in, and they had the most magnificent burnt orange warmups. I thought: ‘My God! I’ve got to get my kids out of here!’ I didn’t want them to see the Texas players. They were the full package!”

Mary Coyle Klinger

Rutgers point guard (1978-1982)

“Texas comes walking in in their beautiful warmups and matching shoes, and they all looked very intimidating. But [my twin] Patty and I were kind of laughing about it because we just had on our pinnies and shirts and red shorts. When we played, I was just glad to have a pair of sneakers that didn’t have any holes in ‘em.”

Jody Conradt

Texas coach (1976-2007)

“I didn’t know a great deal about Rutgers, but I did know about June Olkowski and the twins. They had a reputation in the Philadelphia area for being super competitive, super talented, and there was no back-down in either of them. Trust me: I saw double trouble in those twins through the whole game.

“… We had to rely on quickness and defense. We wanted to extend the court — playing the whole 94 feet in defensive pressure — and score in transition. We were good at that, but I don’t think our experience matched that of Rutgers.”

Mary Coyle Klinger

Rutgers point guard (1978-1982)

“It was said that the Texas backcourt was going to dominate my twin and I. I didn’t understand that. Growing up in the city and the people that we had to compete against day in and day out, I thought, they’re not going to dominate us.

“… Us being from Philly, our whole family was at the game except my father. He was too nervous and couldn’t go. It was funny because he had given us so much of our confidence. His big thing was, ‘Dazzle them with footwork, and everything will take care of itself.’ But it’s the biggest game of our careers, and he’s not there. So one of my sisters, every couple minutes, she’d run out to the pay phone and call and give him an update.”

Sherryl Hauglum

Texas forward (1980-1983)

“Rutgers made two no-look, behind-the-head passes during that game. The timing on their offensive plays was impeccable. They had obviously played together for a very long time to be able to read each other so well. You could tell they had great chemistry.”

Story continues below advertisement

Theresa Grentz

Rutgers coach (1976-1995)

“The reason we were so successful is that Mary Coyle and Patty Coyle handled the ball. Texas put as much pressure on their ballhandling skill as Texas could. Had they been able to strip the ball, it would have been a fast-break free-for-all. But it became a matter of possession and shot-selection.”

Texas, which led 37-34 at halftime, got in foul trouble in the second half, and Rutgers pulled off an 83-77 upset that ended the Longhorns’ 32-game winning streak. The AIAW, which unsuccessfully sued the NCAA for using its wealth to drive it out of business, folded three months later.

Sherryl Hauglum

Texas forward (1980-1983)

“We were used to winning; we never went into a game thinking that we weren’t going to win. So, there was a sadness, a disappointment and kind of a shock. I was disappointed in my play. It was okay, but it wasn’t great, and I felt that I let my teammates down and let Coach Conradt down.”

Theresa Grentz

Rutgers coach (1976-1995)

“We win the trophy, and we’re on the floor, and the [Rutgers athletic director] comes down on the floor and congratulates me. He says to me, ‘I guess this means you’ll want rings?’ ‘That would be correct,’ I said.

“But Rutgers didn’t take us out to celebrate or anything. So, Karl and I, we were just married, took them to a restaurant. They were tired, but I told them, ‘You can have whatever you want.’ It took Karl and I two credit cards to pay the bill, but we paid it.

“And we had rings made and a ring ceremony. We got to ring the bell at Old Queens [an honor Rutgers accords undefeated or champion teams]. And Rutgers did give us sweaters. I still have the sweater that says ‘Champions’ on it.”

Theresa Grentz and her Rutgers team overcame a halftime deficit to beat Texas in the AIAW championship game. (Tom Costello/Courtesy of Whoo-Rah Productions)

CHAPTER 2

‘WE COULD FINALLY BREATHE’

Powerhouses Louisiana Tech and Old Dominion led the AIAW defections to compete in the first NCAA tournament, which had a 32-team field and a nationally televised final. Top-ranked all season, La. Tech was heavily favored, having returned nearly every starter from its unbeaten, AIAW championship season the previous year. In 1981-82, Tech’s roster was awash in talent, led by all-Americans Angela Turner and Pam Kelly, point guard Kim Mulkey, and backup center Debra Rodman, Dennis Rodman’s sister.

Its opponent at Norfolk’s Scope Arena was less anticipated: Cheyney State, a small HBCU 30 miles west of Philadelphia. C. Vivian Stringer was a 22-year-old assistant professor when she volunteered to coach the Lady Wolves in 1971, in addition to her teaching duties. She built Cheyney into a basketball power on a meager budget by instilling belief, toughness and pride while honing her coaching skills under mentor John Chaney, who coached Cheyney’s men.

A capacity crowd of 9,531 attended, and the final was aired on CBS. Tickets cost $5 to $7, and both teams had vocal cheering contingents at the Scope. Cheyney couldn’t afford to bus down a pep band, so Norfolk State’s band volunteered its services.

CHAPTER 3

‘WE WILL NEVER ACCEPT CRUMBS’

South Carolina Coach Dawn Staley sits at the dais the day before the 2022 NCAA regional in Greensboro, N.C., emblematic in many ways of the strides women’s basketball has made since that inaugural NCAA tournament in 1982.

Her top-ranked Gamecocks lead the nation in attendance, averaging 12,268 for home games, and she is among the nation’s highest-paid women’s coaches, signing a seven-year, $22.4 million deal last fall that she hopes serves as a benchmark for greater investment in the game.

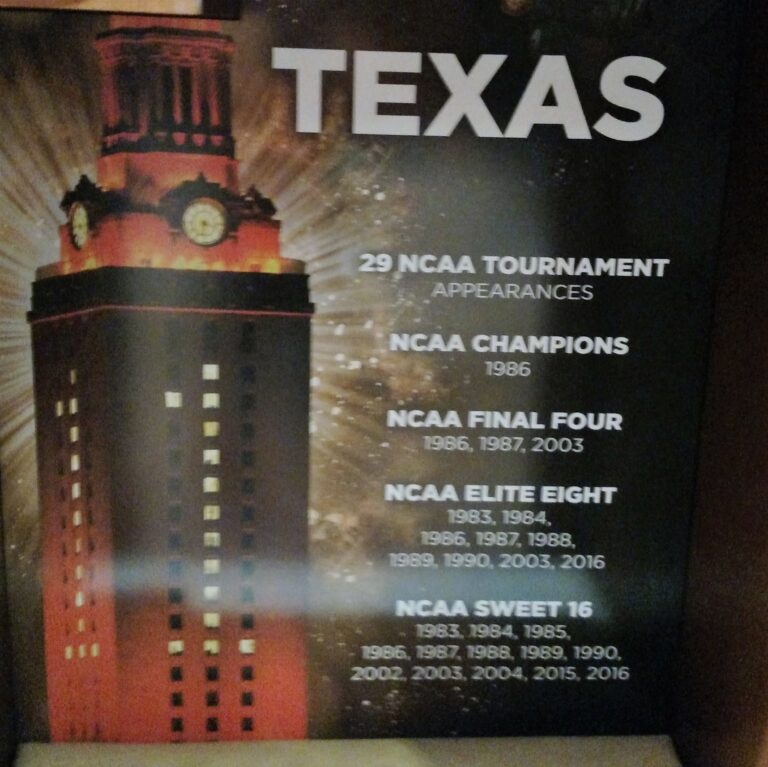

There are other metrics for the sport’s growth under the NCAA.

The women’s tournament has expanded from 32 teams in 1982 to 68 this year.

Seating capacity for the Final Four has doubled, from the 9,500-seat Scope to the 18,067-seat Target Center in Minneapolis

Media coverage has grown exponentially — from 37 credentialed journalists that first year to 716 in 2019, the last pre-pandemic year. And every game of this year’s tournament is televised.

Another metric is the NCAA banner draped behind Staley at each tournament news conference, adorned with a dizzying array of #MARCHMADNESS logos.

The NCAA’s decision to let women promote their tournament with the men’s trademarked “March Madness” slogan — a first, this year — is one example of the low-hanging fruit among several meatier steps urged by the outside law firm that reviewed the organization’s policies after last year’s uproar over the subpar way women were treated in the 2021 tournament. The firm’s scathing report found the NCAA has historically undervalued women’s basketball in myriad ways, from marketing and promotion to broadcast contracts and revenue-distribution formulas.

It is a narrative now four decades old.

After her Lady Techsters won the 1981 AIAW championship, Hogg had championship rings made for the players. After they won the 1982 NCAA title, it took 35 years for the squad to get NCAA rings.

“Maybe they forgot?” mused Turner Johnson. “But better late than never. I was so proud of it.”

Largely lost, too, is Rutgers’ AIAW triumph. That’s why Geoff Sadow, who covered the team’s 1982 season as an undergraduate, has co-produced a documentary, “Forgotten Champions,” weaving an audio recording of the student-radio broadcast with the only known footage of the untelevised game, found in a tin canister in Grentz’s attic decades later and digitized for the purpose.

“This team deserved more accolades than it has gotten,” Sadow said.

The same could be said of each team that reached the 1982 women’s championships.

Laney wonders whether Cheyney State’s 1982 Lady Wolves will ever get their due for reaching the inaugural NCAA title game.

“You can’t forget the history that we made, and we made history,” Laney said. “That team should be inducted into the Naismith Hall of Fame. How do you not recognize the history that was made by this small historically Black college that no one expected to be there except for us and our fans and our families?”

It’s impossible to gauge how the trajectory might have differed — for better or worse — had women’s basketball continued to be run by a separate organization with the interests of female athletes at the forefront rather than by the NCAA, dominated by football and men’s basketball interests.

“I really think we lost 10 years in promoting women’s sports,” said Texas women’s athletic director Donna Lopiano, who also served as the AIAW’s final president. “As soon as women joined the men’s athletic establishment, everybody forgot about promotion and publicity, which is everything in terms of developing a brand and assigning value to the female athlete and value to her product. That’s exactly what schools didn’t do. They put all their money into football and basketball.”

That’s why, under Lopiano’s watch, Texas was among the AIAW holdouts in 1982, even though Conradt wanted to play in the NCAA tournament.

“From a coaching standpoint, I wanted to be there with the big schools and the bright lights and the potential for growth,” Conradt said. “As I look back on it now, I have totally different feelings. I am so proud of the fact, and it was to Donna’s credit and the University of Texas, that we stayed with AIAW that last year, because it became a statement. It was a statement that, ‘Yes, women can control their own destiny. We are not dependent on the NCAA, male-dominated organization to create this opportunity for women’s basketball.”

And on it goes, with each generation of women’s players and coaches pushing for tougher competition, a place in bigger arenas and a national audience despite the NCAA’s track record of selling them short.

“I’ve told my teams many a time,” Stringer said, “We will never accept crumbs.”

About This Story

Photo editing by Toni Sandys. Copy editing by Mark Selig. Design and development by Chloe Meister. Additional development by Jake Crump.