Mark McDonald- The Mauldin’s

Mark McDonald – a long-time sports writer for dailies in El Paso, Abilene, Dallas and San Antonio, now an author in Midland, wrote an insightful article about the Mauldin’s contributions to Longhorn sports. Mark’s story illustrates how the Mauldin family used steadfast commitment and dedication to build a sturdy bridge to our U.T. past. In sports and far beyond, the remarkable Mauldin connection reminds us that our Longhorn heritage lends shape to the present and empowers the future;

In sports and far beyond, the remarkable Mauldin connection reminds us that our Longhorn heritage lends shape to the present and empowers the future;

Stan Mauldin #85 knocks the helmet off the Notre Dame blocker. Joe Theisman is #7. Notre Dame Coach Ara Parseghian is squatting down on the Notre Dame sideline by number 44.

The Mauldin’s: Bridge builders to the past that remind all Longhorns that heritage shapes the present and empowers the future.

Stan Mauldin, the undersized football dynamo, would not only grow from relative obscurity to star at The University of Texas, he would complete one of the longest and most widely successful bloodlines ever recorded in the all-American game.

On the field, in the classroom, in life … Never has one family of Longhorn student-athletes been so good, for so long, in so many ways.

Stan Mauldin Senior

It’s important to know that Stan the youngest did not write the first chapters. No, Stanley Hubert Mauldin was the original, the first in the family chain to reach the Forty Acres, launching a legacy that has spanned eight decades, and counting.

With the Longhorns playing forgettable football in the late 1930s, Stanley Mauldin came out of Amarillo to excel on Dana X. Bible’s teams from 1940-42. Before World War II would stop the world on its axis and send college activities into chaos, Mauldin had emerged as a rangy, rawhide-tough 210-pound tackle. With him leading the blocking up front, the once-failing fortunes of U.T. football became a burgeoning football power on the national stage.

After earning all-conference and all-America honors in the 1940s, Stanley would later fly 25 combat missions for the U.S. Air Force during World War II, then play pro football for the NFL Chicago Cardinals.

Skip to the next generation when son Dan, who played on Coach Darrell Royal’s 11-0 national championship team in 1963. Dan played alongside some of the most recognizable names in U.T. football history … David McWilliams, Scott Appleton, Charles Talbert, Knox Nunnally, Duke Carlisle, Tommy Ford and a jut-jawed redhead named Tommy Nobis. Though he was a fixture on the unbeaten champs, Dan Mauldin was always more serious about his academics, and was proving a keen mind for mathematics.

Dan earned his Bachelors, Masters and Ph.D. at U.T., before going on to a stellar career in mathematical applications in military defense. Today, he works in a California think tank, strictly classified, Dan, now in his mid-70s, walks to work every morning. Once a week, he and kid brother Stan talk via cell phones. They have plenty to discuss.

For one, the Mauldin brothers could talk about how they ever ended up in Azle in the first place. Like the Mauldin connection to Austin, it’s an improbable story in itself.

Dan, then still quite young, and his mother Helen were living in Chicago when father Stanley collapsed and died in the Cardinals locker room after a 1948 game against the Eagles. He was 28. Unbeknownst to Stanley, the deceased was about to become a father for the second time. In the swirl of time and events, Mom had not yet had a chance to tell her busy husband the good news.

Pregnant mother and son Dan moved from the Windy City to Greggton, Texas, a Longview-area town in the Pineywoods where Helen’s mother lived. Three years later, Helen Mauldin met an aeronautical engineer named C.J. Dowling, “a fine, fine man … but an Aggie,” son number 2, Stan, today says with a chuckle.

Helen and C.J. would marry, just ahead of a major transfer. The U.S. Air Force would send the Dowling couple, along with Dan and 3-year-old Stan, to Japan during Korean conflict. From there, the family was shipped to Lincoln, Neb., where Stan doesn’t remember much about starting to kindergarten, except for “walking to school in the snow.”

Once he fulfilled his duty, C.J. Dowling got out of the military, took a job with General Dynamics, which became Lockheed-Martin and moved the family again, this time for good. In 1955, Dan and Stan settled in a home in Azle, just outside Fort Worth.

Stan Mauldin “The Younger”

Stan Mauldin “the younger” stops short of saying he was banned from playing football. Just as Coach Darrell Royal was discounted for his lack of size, Stan Mauldin — the flyweight seventh grader — was discouraged from going out for Azle’s eighth grade team.

“Why, son,” the junior high coach said, “you don’t weigh more than a sack of potatoes.”

So began, but nearly didn’t, a widely acclaimed – and most unlikely – love affair with football that, for Stan Mauldin, has lasted his whole life. Along the way, he earned a special place in the deep and colorful lore of U.T. athletics.

With Dan taking the lead, Stan developed an instant liking to the mental challenge and the physical nature of football.

“Dan encouraged me into football just by way he handled himself,” Stan says. “He’s unusual for such a good football player, in that academics were always much more important to him than his athletics.”

Coaches in Azle had to cajole Dan into coming out for football.

“I didn’t think I could get him to play,” says Don Hood, who went on to a hall of fame coaching career in track at Abilene Christian University. For such a reluctant astronaut, Dan flew far and fast, winding up playing end for Coach Royal’s undefeated team that beat Roger Staubach’s Navy Midshipmen in the Cotton Bowl.

Stan Mauldin and Syd Keasler- Lifetime friends

Come his turn, Stan says, “I still wasn’t very big or very fast, but the coaches didn’t have any trouble getting me out there.” He would play his varsity ball for James Teeter, a highly respected coach and what Stan calls a “positive influence on young people.” So positive, in fact, that Stan made all-district as a 180-pound fullback and linebacker – but not so positive that Azle was a bright push pin on the recruiting map of Penn State, Nebraska, Notre Dame, Alabama, Southern Cal or even his first choice, Texas.

Stan had small-school offers, all right, but nothing that stirred him into signing. Then one day the phone rang, and here’s where the Stan Mauldin story gathers momentum.

It was Darrell Royal.

“Coach said he didn’t have a scholarship to offer but said, ‘I really think you ought to come down here to Austin and give it a try.’ I always had a lot of respect for Coach Royal, so I just had one question for him: Are you going to give me a chance.”

Royal had a ready reply: “Yes, you will get your chance. I will make sure of it.”

When Stan hung up the phone, he would have crawled on his hands and knees from Azle to Austin.

“A chance, that’s all I needed,” Stan says. “I felt confident. I wasn’t very big, maybe 185 pounds, I didn’t have the wheels. I ran a 4.9 (40-yard dash) … maybe.

“I had been looking at Abilene Christian and thinking about going to Texas A&I (now A&M-Kingsville). But I would say I had the quickness. I thought I could make it (at Texas).”

That didn’t mean that the youngest Mauldin, U.T. legacy or no, would be greeted with a downtown parade.

During the state high school track meet that spring, Stan and a buddy hitch-hiked to Austin and, without a motel room, wound up sleeping in the pole vault pit at Memorial Stadium. More reality would soon follow.

In those days, freshmen nationwide were prohibited by the NCAA from playing varsity ball. Stan bided his time on the freshman team, then the spring of 1968, his first shot at making an impression. At Texas, and so many other schools, the depth chart was posted on the locker room wall, with names of each player hanging on a metal hook. Starters were on the first rung, second-stringers on the second. Stan kept looking and looking until he found his name.

Eighth string.

Surrounded by proven lettermen such as Bob McKay and co-captains Glen Halsell and James Street, along with the heralded recruiting class of 1967 called the “Worster Bunch,” for high-profile fullback Steve Worster, Stan’s status could have been no lower. Issued a blue jersey, he was assigned to the so-called “attack squad,” comprised of surplus humans, used as blocking dummies and tackling targets – raw meat for the starters to sharpen their fangs. Better to be the back end of a shooting gallery than to be on the attack squad.

Stan looked around, saw scholarship players who didn’t have the chops and started climbing toward daylight. Actually, he started hitting anything that moved.

“I was really determined, every day,” Stan says. “Any chance I had to show I could play, I had to jump on it. Face it, I wasn’t coming in with any position (status) at all. I took every opportunity, I could. I didn’t go slow anywhere.

“The timing for me was very unusual. Spring training of 1968, the coaches were under duress. The team had gone 6-4 three straight years. Another one, and they might all get fired. They were determined to change things around here.”

Coach Royal and his staff were not looking for glamour, they were looking for pure-dee football players. What he called “dipped and vaccinated” Longhorns, rangy kids who, in coach-speak of the day, would hitcha.

“For somebody like me, it was great timing,” Mauldin says. “Coaches didn’t care if you were a blue chipper, or if you came to town on a load of wood. Actually, I think I did just that. I came in on a load of wood. I was looking for a better deal.”

His first semester at U.T., Stan didn’t sleep in the pole vault pit, but his room in Moore-Hill Hall, not in same area with the other players. Instead, it was upstairs, where he roomed with a “civilian” named Graham Hill, a pre-law student from Houston. (Turns out, Graham was the son of John Luke Hill Jr., the only person to serve as Texas Secretary of State, state attorney general and Chief Justice of the Texas Supreme Court.)

Stan’s big break, if you could call it that, came when Defensive Coordinator Mike Campbell called for an older player to step into a drill opposite Leo Brooks. A defensive tackle in the Scott Appleton-Diron Talbert mode, Brooks was listed at 6-5, and 244 pounds, but later admitted his playing weight ranged up to 260, a mountain of a man in those days. Before Campbell could look twice, a smallish kid in a blue shirt had jumped into the fray, a classic mismatch that surely would end up in Frank Medina’s training room.

First play … wham … a fierce collision of two willing competitors. Second play … blam! … another practice field car wreck.

When the dust cleared, Stan Mauldin was still standing. He had not conquered the giant, but Leo Brooks, who would go on to a Pro Bowl career with the NFL Cardinals, had not run roughshod over the 185-pound blocker. And most of all, Stan had won over his immediate supervisor.

Tweet! All players freeze, and look to Coach Campbell.

Dinner for you Mr. Mauldin

“Come here, son,” bellowed Campbell, a no-nonsense survivor of WW II. “You are going to eat steak tonight. Hear me? Steak!”

Sure enough. That night, in the chow hall where scholarship players always ate at separate tables from walk-ons, Stan was set aside again. This time, while the favored ones ate chicken or hamburgers, Stan sat down to a steak dinner, with all the trimmings. He had a table to himself, and his own waiter.

More than anything else, he had carved out the grudging respect of the locker room and, so it is, the Stan Mauldin story takes a new turn. Coach Royal singles him out the next day at practice, saying “from now on, Mauldin, you eat with the scholarship players.”

The Longhorns’ roster was loaded with linebacker talent — Scott Henderson, Glen Halsell, Corby Robertson, and coach’s twin son Mike and Tom Campbell — so Stan was red-shirted in 1968. But beginning with that first spring, he was in the mix. Though he never played at more than 195 pounds, Mauldin captained the 1970 team that won the old Southwest Conference, losing only to Notre Dame in the Cotton Bowl, for a sterling 10-1 finish. Here’s where Stan’s former teammates could be penalized 15 yards … for piling on.

“I had heard about his brother, Dan, on the 1963-64 teams,” says Bill Atessis, a Longhorn defensive end who also played in the NFL. “I didn’t realize what kind of player Stan’s Dad was. Then I saw his father’s plaque on the wall in the Longhorn Hall of Honor … That was impressive. But being around Stan, you would never know it.

“Stan was one of those unassuming guys, humble with a great sense of humor. He and Charlie Crawford and Tommy Matula would sing or imitate the Marx brothers, in dorms or in team hotels when we traveled.

Like other former teammates, Atessis talks about Mauldin’s flawless technique, his leverage, perfect technique. “Stan was like (guard) Mike Dean,” Atessis says. “Neither was very big, but size didn’t matter.”

Two other teammates point to Stan’s reliability and consistency.

“He was a quiet leader,” says Scott Palmer. “He sure had the genes for it.” Palmer should know these things. Scott’s father, the late Derrell Palmer, was an all-America tackle at TCU. In fact, Derrell Palmer and Stanley Mauldin the eldest played against each other just before WWII.

“Stan was steady,” Scott Palmer says. “A smart football player. He was one of those guys who knew the defense, not just what he was supposed to do, but where everybody was supposed to be, too. Tough as a boot.”

Former offensive tackle Bob McKay, a 2017 inductee into the College Football Hall of Fame, says, “You never had to go looking for Stan Mauldin. You knew right where he would be, every play. And that was usually around the football.”

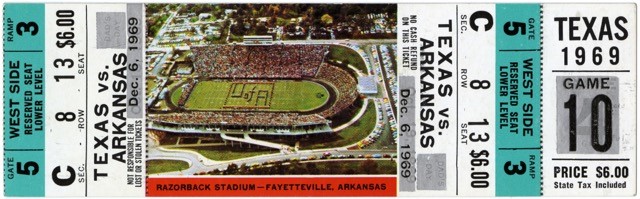

Another Longhorn standout from the 1960s, David Arledge — himself an undersized defensive player from the Dallas-Fort Worth area – agrees that Stan Mauldin was cornerstone to the U.T. success. Arledge, at 175 pounds, provided relentless pass rush on quarterback Bill Montgomery in the Arkansas-Texas Big Shootout for the 1969 title. He recognizes quality when he sees it.

“You don’t see many former players our age who have low esteem,” Arledge says. “We grew up with parents and played for coaches from the WWII era. We were expected to stand on our own two feet. When Stan got here, coaches just threw us all in one big pot. Let’s see who comes out on top.

“Stan had a work ethic. Guys called him ‘Rattlesnake’ he was so quick. He just refused to lose.”

What does Arledge remember most about the youngest Mauldin?

“Right from the start, he wanted to be a coach, always,” David says. “He got a job as a grad assistant under Bear Bryant at Alabama. Coach Royal recommended him. That was Coach Royal’s way of taking care of his own.”

Schools where Stan taught and coached: over decades of service, he variously held coaching and athletic director positions at Klein, Georgetown, Bellville, Alvin, Austin High, finishing his stellar career at Hyde Park Baptist High School in Austin, where he coached with former U.T. kick returner Dean Campbell.

At every stop, Stan Mauldin instilled his winning ways on the players he coached. When it comes to leaving a lasting impression on young people, Stan is a leader in the clubhouse.

“Every now and then I will run into somebody who asks if I played football,” Arledge says. “When I tell the guy I played at Texas, he will say, ‘Do you know my high school coach, Stan Mauldin?’ To a man, every one of them will say ‘he made a great impact on my life.’”

To David Arledge, and so many of his Longhorn teammates, earning such acknowledgement, in such a challenging industry, is to have a magic wand, with professional poofy dust.

“This is the kind of ratification you can’t buy,” Arledge says. “Momma can’t hand that to you. Daddy can’t buy it for you … What a great testimony for somebody to say about you.”

Stan Mauldin might shrug it off, dismiss it all as part of his Longhorn heritage. Then again, he knows what it is like to be knighted, to be honored with a seat at the round table. Maybe even to have your own personal waiter.

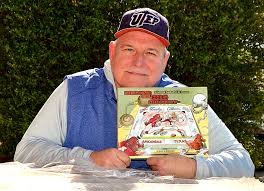

Author Mark S. McDonald, Sr. is a former Texas-based sports writer who played what he describes as forgettable football in Spring Branch, Roswell, N.M., Midland Lee and UTEP (B.A. journalism). For the past year and a half, he has revisited the football culture and social climate of America during the chaotic late-1960s. The resulting book, his ninth, entitled Honor & Pride – The Arkansas-Texas Shootout, is to be released in mid-2018. McDonald may be reached at mark.mcmarketing@gmail.com.

One Comment