CTE’S Impact on Longhorns

Part II of “A Trilogy + 1 “of football and neurodegenerative diseases

Did helmets give athletes and Coaches a false sense of security that their heads could be used as A battering ram?

The NCAA made helmets mandatory in 1939, according to “The Anatomy of a Game: Football, the Rules and the Men Who Made the Game,” by David M. Nealson.

Click on the link in red below for the history of helmet design.

https://www.texaslsn.org/helmets-jerseys-shoes-and-more

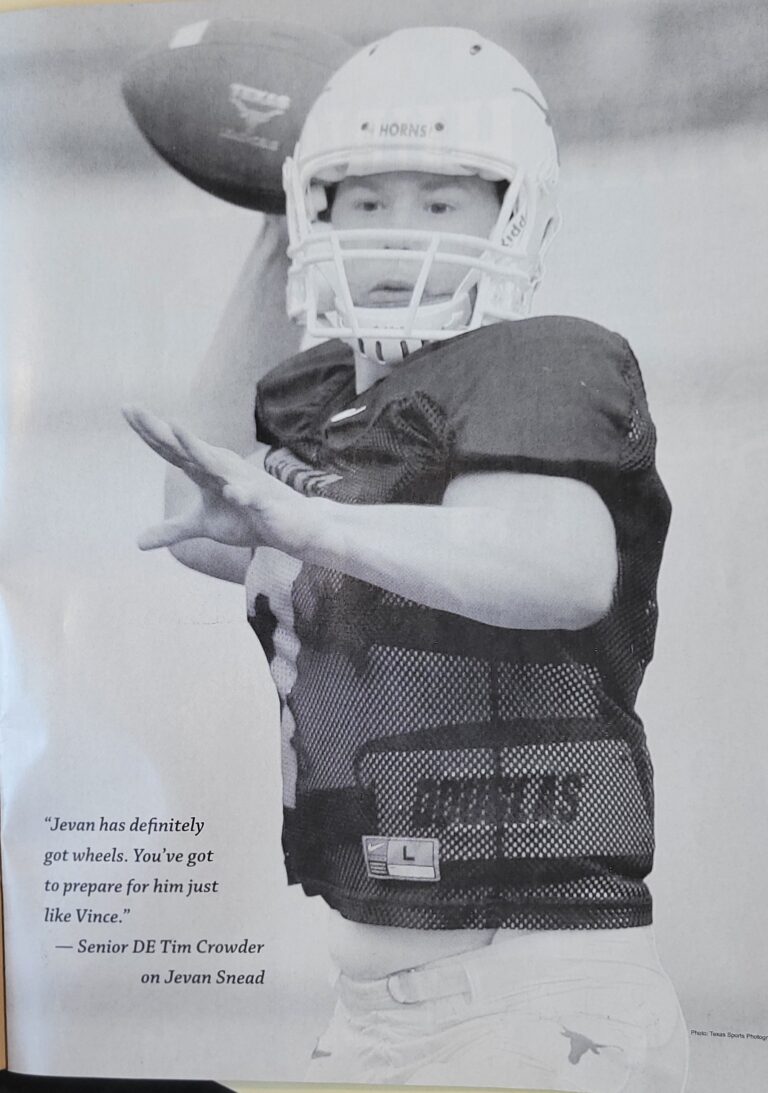

Helmets changed football blocking, defense, running, and tackling techniques. The head became a battering ram, sometimes resulting in what was euphemistically called getting your “bell rung.” However, Bell ringing was never considered a life-altering event until boys turning into men impacted by head trauma in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s started passing away from a neurodegenerative disease. While this article is a never-ending story with more research to follow, to date, the 1971 football team incurred the most cases of neurodegenerative disorders. The link in red font tells the story of the 1971 team. The list includes Julius Whittier and Larry Webb. Travis Roach, Greg Ploetz, Malcolm Minnick, Greg Dahlberg, Bill Wyman, Jimmy Moore, and Jim Bertelsen. See the link https://www.texaslsn.org/1971-a-team-thathas-paid-the-ultimate-pricefor-victory

In reflection, many former football players now believe the cost of glory is too high for body, mind, and soul. The final stages of cognitive deterioration are immediately apparent to friends. The infirm no longer smile or speaks, and their eyes reflect an empty soul.

Gordon McNulty, an Arkansas Razorback who played in the 1969 Big Shoot-out, says, “We become addicted like gladiators to the roar of the crowd. We lose our true identity and develop an identity contrary to what we were meant to be.”

On the other hand, many former players believe as Sonny Liston, who, when asked if children should be allowed to play a contact sport, said, “Who am I to tell a bird he can’t fly?”

Coach Royal was also a high school and college football player who took many punishing hits. It may be one of the reasons his memory failed him and Alzheimer’s crept into his later life.

Larry Webb and Dan Terwelp- Some souls understand each other immediately

Larry Webb, Longhorn football (68-72), died on 2/3/19 in a hospital bed in the loving arms of his wife, Mary Jane. Larry suffered from CTE. He could not leave his house because of daily nausea, vertigo, and mental decline. He ultimately died from Renal Cell carcinoma and was in hospice since his diagnosis in October 2018.

Mary Jane had him at home until the Wednesday before his death. He was in tremendous pain up until his death, so his passing was a blessing to him and MJ. His brain was sent to Boston for analysis. He was diagnosed with CTE.

Really going to miss Lawrence of Angleton, “Old Catfish Mouth,” said his teammate and best friend, Dr. Dan Terwelp.

Update 01/09/2020 from Dr. Dan Terwelp about Larry Webb

Hi Billy and happy new year. I heard from MaryJane Webb, and the neurologists and pathologists in Boston that examined Larry’s brain completed their work and called her. They found multiple Tao deposits in his frontal lobes.

Tao deposits are proteins that accumulate in patients suffering from CTE and Alzheimer’s disease. They classified him as stage II CTE. Remember, he didn’t die of CTE, but he would have if he hadn’t had Renal Cell Carcinoma (kidney cancer). Mary Jane told them they could use his information for any presentations or research that they were performing. She said we could share this information also with anyone. They had talked about it before he died that he hoped some of this information might help this new generation of athletes. The anniversary of his death is next month. She said she would never be right without Lawrence of Angleton, as we all affectionately called him. He was one of a kind.

Tommy Nobis had the worse kind of CTE.

The San Antonio Express News article by Mike Finger June 2, 2018 .

This combination of photos provided by Boston University shows sections from a normal brain, top, and from the brain of former University of Texas football player Greg Ploetz, bottom, in stage IV of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. According to a report released on Tuesday, July 25, 2017, by the Journal of the American Medical Association, research on 202 former football players found evidence of a brain disease linked to repeated head blows in nearly all of them, from athletes in the National Football League, college and even high school. (Dr. Ann McKee/BU via AP) less

Mildred Whittier’s court date is set for the courtroom in 2022. It has been five years since she filed a lawsuit against the NCAA on behalf of her trailblazing brother, who battles dementia almost five decades after he became the first black football letterman in Texas Longhorns history.

mfinger@express-news.net<mailto:mfinger@express-news.net

Twitter: @mikefinger

As Julius’ roommate, I have written his story and about the black history of Longhorn football.

Article in Dallas Morning News about Greg Ploetz by Kevin Sherrington in 2015

Greg Ploetz hasn’t played a football game in more than 40 years, but the scar still shows. An undersized All-Southwest Conference defensive tackle at Texas, he earned it. A “warrior,” one teammate called him. Now, at 65, Ploetz can’t handle crowd noise. Conversations confuse him. Walking is sometimes terrifying. In his tortured mind these days, a crack in the floor looms like a leap across a deep, dark crevasse.

Ploetz — pronounced Plets — suffers from what neurologists call “mixed dementia,” the probable result of head trauma from his days as a 5-11 205-pound lineman at Sherman High and Texas. Doctors can’t tell his wife, Deb, if he’s a victim of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, known as “CTE,” the progressive degenerative brain disease linked with multiple concussions.

One of Greg’s last paintings while struggling with CTE, signed by 250 DKR players

Julius whittier by Millie Whittier

UT ex Julius Whittier battles Alzheimer’s as his sister takes on the NCAA

Mike Finger Sep. 16, 2017 Updated: Sep. 16, 2017 8:33 p.m.

Mildred Whittier did not need to know.

Looking back on it, almost five decades later, she can appreciate her youthful naiveté as a gift of kindness from her big brother. She was only a sophomore at Highlands High School when Julius Whittier went off to college in Austin, and she had no idea he was doing anything out of the ordinary.

Julius was going to attend school, and he was going to play football. Simple as that.

Even if he understood everything that went along with integrating the Texas program and becoming the first black letterman in Longhorn’s history, there was no reason to tell his younger sister.

“I didn’t understand the enormity,” Mildred said. “The fact that he was the first African-American didn’t move me one way or another. I wasn’t caught up in him doing anything historic. He was just my brother.”

Now, all of these years after he left his mark on the football field and in the courtroom, there is something Julius does not need to know. By not mentioning it, Mildred is returning a gift to him and keeping him unaware of another enormity.

Julius has Alzheimer’s disease.

“I never can tell him that,” Mildred said. “I don’t think he has made the connection that you have dementia, that you have Alzheimer’s. He says he’s forgetful. He says, ‘I have to rely on my sister.’ ”

Pushing for change

Julius Whittier North entrance to DKR stadium. Julius was my roommate.

In a way, others are depending on Mildred, too. In 2014, she filed a class-action lawsuit on Julius’ behalf against the NCAA in U.S. District Court. The suit seeks up to $50 million in damages for players from 1960-2014 who did not go on to play in the NFL and who have been diagnosed with a latent brain injury or disease.

That case is separate from a proposed settlement in which the NCAA agreed to set aside $75 million for brain trauma research and testing for current and former athletes. But that settlement offers no financial compensation to injured players, and the goal of Mildred’s lawsuit is to establish a fund for the supplemental needs of those suffering from the effects of brain trauma.

The lawsuit claims the NCAA “was fully aware of” and “concealed the dangers of” head impacts in football.

As Mildred watches how the 66-year-old Julius’ mind has deteriorated, she remains convinced his days as an offensive lineman and tight end caused it.

“No doubt at all,” Mildred said. “He continually spoke of how he was trained to block, using his head. For someone who was as brilliant and as vital as my brother, it’s just sad. I’ve cried so much, I don’t think I can cry anymore.”

Mildred’s cried with former colleagues and teammates of Julius who have stopped by the north Texas memory care facility where he now lives. She can tell he realizes he’s supposed to know these old friends, but he doesn’t, so he just smiles and laughs.

She has cried with Deb Ploetz, the widow of one of Julius’ UT teammates. Two years ago, Greg Ploetz died at the age of 66, and was found to have been suffering from Stage 4 Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). Deb, who told the Denver Post her husband would have chosen never to play football “if he knew he would suffer and die like he did,” filed a separate lawsuit against the NCAA last January.

“She wanted to stay in touch with Julius and stay in touch with me,” Mildred said of Deb. “I think she needed somebody to relate to.”

What Mildred and Deb understand is how brain conditions overwhelm not only the patients but also everyone who love them. It begins with a couple of troubling signs, and then a few sleepless nights, and eventually it becomes too much for a man or a woman or a family to bear on its own.

A quick descent

For Mildred, it started in 2012, when the leadership team of Julius’ law firm asked her to attend a meeting. He had been in private practice for more than two decades following his stint as a Dallas County assistant district attorney.

He was only 61 at the time, a year away from his long overdue induction into the Longhorns’ Hall of Honor. The memories of his days at UT, where as a freshman in 1969 he dealt with the often-difficult circumstances of becoming a racial pioneer and then earned his historic varsity letter in 1970, were still vivid.

But other parts of his mind were slipping, and his fellow attorneys noticed. He would drive to a lunch or a meeting, and wasn’t sure where he was supposed to go after that. His bosses told Mildred it might be best if he stepped away from the job.

For a while, Julius continued to live at his home in Oak Cliff, not far from Mildred’s work as a systems analyst for the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. She would stop by to eat lunch with him every day, and before long she was attending to some of his hygienic needs, too.

“He started to wander,” Mildred said. “He was not able to cook on his own safely, manage himself. I suspected (Alzheimer’s) but I didn’t want to face up to it. Telling a brother that has been so full of vitality his whole life, it was not easy for me.”

Then came a fire at Julius’ home, and Mildred used that as a reason to get him to see a doctor. She told him he’d been through a lot of trauma and needed to get “checked up.”

He agreed, reluctantly, and Mildred’s fears were confirmed. He had early-onset Alzheimer’s, and things were only going to get worse.

For a while Julius lived with her in Plano, but in 2016 he moved to the memory care facility. One of his former UT teammates, who has visited the home but asked not to be identified because of the pending lawsuit, confirmed Julius no longer recognizes him.

For the future

Mildred believes this can be prevented. She says one of the main reasons for her suit is because “football is big-time, and we have to do what we can to make sure more people don’t suffer through this.”

When she filed the suit, Julius knew about it, and was all for it. She says he told her he was glad to be in a position to address the problem, and hopefully to find a solution for those who followed him.

He is not aware of the legal proceedings anymore, though. He does not realize he is suffering from a terrible, cruel disease. Medication keeps him drowsy most of the time, and Mildred says his spirits seldom get lifted.

“I am so happy to say that when he sees me, he lights up,” she said. “But then he starts crying. Deep down inside, he understands he might be missing something.”

He does not need to know what it is. Only the rest of us do.

George Sauer

Sauer was an under-utilized receiver in Darrell Royal’s run-heavy offense. His father, a former college star for DX Bible at Nebraska and a former Green Bay Packer, was personnel director of the Jets from 1962-69 when clubs in the upstart American Football League were desperate to find the talent they could lure away from the NFL.

The Jets hit the jackpot with the quartet from Texas.

“All of us wound up being better in the pros than we were at Texas,” Lammons said.

Sauer had an extremely productive career. He was chosen to four all-star teams and was a two-time All-Pro.

In a largely defensive struggle in Super Bowl III, Sauer had eight receptions for 133 yards — more catches and yards than he had for the entire 1963 season at Texas.

The team and Moreland Funeral Home in Westerville confirmed that George Sauer died after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s disease.

In 1970, Sauer walked away from football, turning his back on a sport he called “inhumanly brutal.” In 1972 he penned the introduction to “Meat on the Hoof,” a still controversial expose of the brutality of UT football.

After Sauer lost his father to Alzheimer, he wrote a poem that captured his sorrow and a premonition that he might suffer the same fate — “an old man dances in my mind his broken brain rattles mine.” Sauer never finished his novel. Alzheimer’s began to take its toll.

“He became something of a hermit,” Lammons said.

Sauer passed away in 2013. According to published reports, no one from his college or pro playing days attended his funeral.

https://www.texaslsn.org/george-sauer-conflicted-soul

THE VIDEO OF JIM HUDSON AND GEORGE SAUER STARTS AT THE 2:56 MARK AND THE 8:45 MARK IN THE MOVIE BELOW

James Saxton

By Brian Davis

Posted May 29, 2014 at 12:01 AMUpdated Sep 25, 2018 at 9:17 PM

James Saxton, former Texas running back who coach Darrell Royal once called the “quickest player in America,” died early Wednesday after battling dementia. He was 74.

Jim Hudson

Hudson and Sauer succumbed to the head injuries and/or mental conditions that have now been linked to the epidemic of concussion-related problems in college and professional football. Most of the news about chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) has centered on the dangers of pro football but Pete Lammons said, “Oh Lord. Mercy. We had a lot more hitting in college practices.”

In 2013 Hudson died from what was first diagnosed as Parkinson’s disease but was later discovered to be a very advanced case of CTE.

Professionals said, “Up until recently, it was the most damaged brain they had seen”. He died in 2013 of dementia; a postmortem study of his brain found that he suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the life-altering disease that has beset numerous former NFL players.

In an interview at her home in Austin, Texas, Lise Hudson described her husband’s idyllic post-football life, breeding and training quarter horses, hunting and fishing with their kids. “If you think of the Marlboro Man, he was it,” she said. Then things changed. Jim Hudson went to the wrong school to pick up his daughter; it seemed funny at the time. Years later, hand tremors, financial errors, and a routine trip to the supermarket ended with him wandering lost in a parking lot. Hudson died in 2013 with what was originally thought to be Parkinson’s dementia but was later diagnosed as CTE, which is caused by brain-killing clumps of a protein called tau. Originally studied in boxers in the 1920s, CTE has been linked to repeated head trauma; its prevalence among football players has forced the powers in the game to rethink the rules about how the sport should be played, and who should play it. “I hope it doesn’t kill the game, but that it stops killing the players,” Lise Hudson said. “We’d better get on it and figure it out.”

Some were called “stingers.” Other times he “got his bell rung.”

Roy Jones remembers Jim Hudson

I was George Sauer’s roommate in Moore-Hill Hall and senior manager of the 1963 Longhorn team. One of my favorite memories of Jim was a freshman game (before freshman could play varsity). We got the ball at our own one and on first down, Jim ran a quarterback sneak to have a little room to operate. The QB sneak went for 99 yards and a Shorthorn TD.

Marvin Kubin

In lieu of flowers memorial contributions may be made to the Alzheimer’s Assoc., Rocky Mountain Chapter, c/o Keith Swanson, 455 Sherman Street, Denver, CO, 80203 or the Arkansas Valley Hospice, PO Box 408, La Junta, CO, 81050 direct or through the funeral home.