When water was for “sissies”

Football player Jordan McNair from Maryland, Reggie Grob from Texas, and Joe Good, a Fictional Character from West Texas, all died of heat stroke.

Stopping heatstroke deaths requires adequate hydration by coaches and trainers who understand both the causes and symptoms of heatstroke.

On September 1, 1962, Reggie Grob, a Texas football player, was rushed to the hospital with a core temperature of 106. He died two weeks later.

On May 29, 2018, Jordan McNair, a Maryland football player, was rushed to the hospital with a core temperature of 106. He died two weeks later. Fifty-six years of relevant heat stroke research separated these two tragic deaths, but for Jordan McNair, on this day of infamy, research on what precipitates a heat-related death was forgotten.

The story that follows tells the story of a fictional character named “Joe” and his coaches who missed all the signals that lead to Joe’s heatstroke death.

When water was for Sissies 1950’s – 1962 By Billy Dale

Dehydration

Joe Good is a fictional football player trying out for the Core Heat AAAAA High School football team in a West Texas town in 1961. It is a time when Coaches still believe that drinking water during football practice was for sissies. During the first 4 minutes of conditioning drill on the first day of training on a hot, humid day in late August 1961, Joe Good becomes another statistic of the “water is for sissies” conviction.

Joe dies when his core temperature reaches 106 degrees, and all his organs shut down. In 1961 medical professionals were still researching the significance of dehydration in the death spiral. Joe Good died because dehydration made his blood thicker, which increased his heart rate and decreased the amount of blood his heart could pump with each beat. To exacerbate Joe’s problem, dehydration made it harder for his fat to get into his muscles to be used for fuel. Instead, his muscles burned the limited sugars (glycogen) already there.

Since the full dynamics of the role dehydration plays in heat stroke was unknown to the Coaches in 1961 at Core Heat High School, they continued to follow techniques learned from past generations of Coaches. Bear Bryant’s Coaching style from the ’50s was one of them.

In Junction Boys by Jim Dent, he says that Bryant was aware of a couple of deaths due to heatstroke in 1954, but one of his trainers reasoned, “Hell, you never pour ice water into a car’s hot radiator. So why pour ice water into a hot boy.” That logic almost cost the life of Billy Schroeder at a practice in Junction, but even after watching one of his players almost die , Coach Bryant still did not permit water at practice. The cottonmouth was prevalent, and even the great Jack Pardee said: “I’m so thirsty that I can’t even make spit.”

All the players at Core Heat High School knew not to ask for water during work-out because it was tantamount to admitting to a character flaw. The other myth passed down from coaches in the ’40s, and ’50s stated that screaming, cajoling, and spewing insulting remarks at players was a proven “motivational” technique.

It was during conditioning drills that all these motivational techniques came into play, allowing Coaches some insight into the “character” of their athletes. It was time to separate the “sissies” from the “men.”

In Junction Boys by Jim Dent, Coach Bryant asks two seniors, “what is wrong with the team?” Marvin Tate responded, “……players are getting tired of being cussed all the time.” “I’ve never been called so many names in my life, Coach. Every time I turn around, one of the coaches is making fun of somebody’s mother.”

On the day of Joe’s death, his brain sent him a message. It said slow down because you are fatigued and your core temperature is rising. Joe did exactly what his mind said, but the Coach interpreted Joe’s slower pace as laziness and gave Joe a symbolic “kick in the butt” using cajoling and derogatory remarks as the “motivational” techniques of choice.

Screaming, cajoling, and insults may have worked on some athletes, but it was a flawed motivational technique for Joe’s personality. Joe was a proud and needed no motivation from the coach. He wanted to make the team at all cost so the verbal kicks were not effective. The Coaches comments only served to embarrass him in front of his peers. According to Coach Darrell Royal “When you take pride away from a player, you’ve destroyed the best tool you’ve got. If you hurt him, you’ve hurt the team.”

Joe’s pride was hurt, but his motivation to make the team remained intact. Joe was a normal 17 year old boy trying to find his way in life. He wanted recognition and a sense of belonging, and football offered him that chance.

Joe wanted the adoration of all the pretty girls , attention at parties, respect from peers, and recognition from the residence of his hometown. He had no desire to play beyond his high school years, and a college education was not in his future. Making the team would be a significant benchmark in his life. Joe was willing to use samurai warrior techniques to make the the team so he pushed himself harder during the conditioning drills.

Joe’s decision to push harder when his mind said, slow down was the final wrong decision in a perfect storm of events that took his life. Joe’s positive attributes- hard work, determination, and his never quit mentality- combined with a hot, humid day, a coach who pushed too hard, and his refusal to listen to his body killed him.

If only one of these factors had not been present, Joe would still be alive. Joe’s death was only covered locally. A reflection of the national mindset of the media and general populous in the ’60s. A death of an athlete at practice was not worthy of national news. Everyone, of course, was sad at Joe’s passing, but fans who loved football understood that “inherently uncontrollable risks” are part of the game, and Joe knew that risk. One year later, two events will shock the sports world. Fans would learn that dying from dehydration is not an inherently uncontrollable risk. It is, in fact, controllable and preventable.

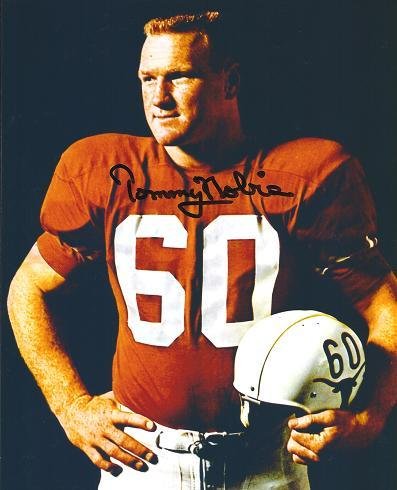

Most coaches at the university level before 1962 believed that players asking for water were sissies. Royal also adhered to this belief. Coach Royal wanted tough players, so he had tough workouts with lots of conditioning. I know because I played for him in the late ’60s. Royal said, “Football is a physical contact, spartan game. You don’t go out there for any taffy-pull……” Under Royal’s regime, only the strongest survived.

In 1962 two real heat-related deaths in the SWC exposed the belief that water is for sissies as a fraud. It would forever change the dynamics of hydration at practice.

Pat Culpepper played ball for the Horns in the early ’60s, and he wrote an Orange Blood thread about what happened in 1962 that finally exposed “water is for sissies” as a lie.

He says, “We (Longhorns) had come through two weeks of full pad practices in the Austin heat and humidity. There were water breaks for the first time because of heat problems around the Southwest Conference. We had five players taken to Breckenridge Hospital with heat dehydration. Only one never made it back – Reggie Grob from Houston. He died along with Mike Kelsey, the senior captain from SMU.

Mike survived for 17 days before succumbing to liver and kidney failure. Reggie, at 19 years of age, succumbed to heat stroke around the same time. At the time of Reggie and Mike’s passing only salt, tablets were offered to reduce dehydration during practice.

Doctors thought the new plastic shoulder pads had something to do with these two heat-related deaths. Culpepper says, “Most of us wore expensive leather shoulder pads that actually got wet with our sweat which let some air through the jerseys while the plastic pads encased the player and did not allow any air. Before those youngsters died, we never got water breaks, but our head coach Darrell Royal, as other coaches, learned a tragic lesson. We went to Reggie’s memorial service in Houston as a team in two buses on Monday before our first game.”

In the book Texas Caesar by J. Brent Clark the author says “on September 1st 1962 the first day of beauty grueling two a day practices a combination of commitment and excessive pride claimed Reggie grove’s life. It was said later that coast Royal authorized Reggie to be the first walk on at UT to also be awarded a scholarship. “

According to Jones Ramsey (Sports Information Director), Coach Royal was devastated by Reggie’s death and “collapses and cries” in the enormous arms of Defensive Line Coach Charley Shria.

Bill Little said about Reggie” In a very real sense, his death meant that thousands and thousands have lived. Out of tragedy, he gave us all a gift. And that’s why he’s a legend”.

Juan Conde says, “I was already working as assistant equipment manager when Reggie passed away from heat exhaustion. I also recall Frank Medina tending him vigorously and the arrival of the ambulance. This incident took place at the old practice field across the creek and across from memorial stadium where practices were held. Coach Royal took Reggie’s death very hard.”

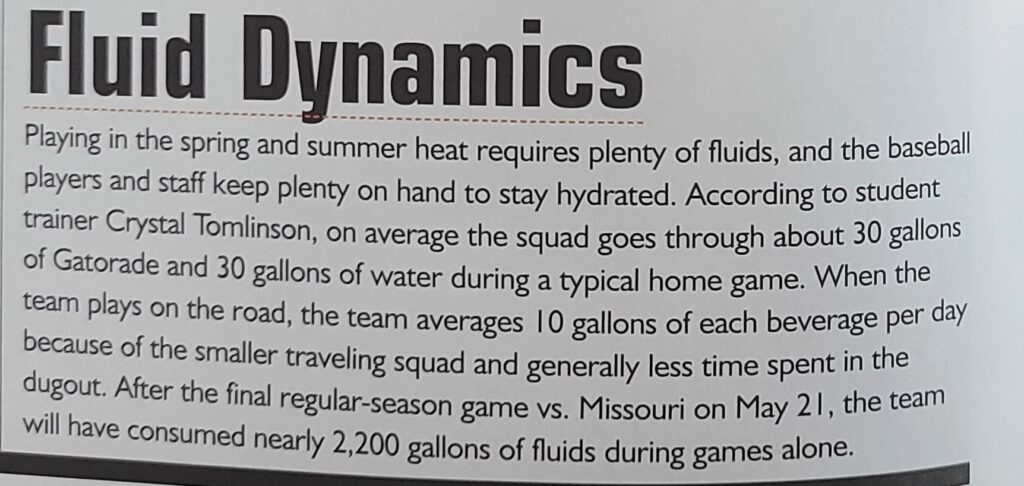

The death of Reggie and Mike was a wake-up call for all who are associated with sports. Doctors, led by the American Medical Association, began immediate research on the effects of heat on the human body. Within a year, Universities mandated more liquids for athletes during workouts and games.

At the high school level, changes were slower. Some states were proactive and moved quickly to change workout routines. State athletic associations and individual school districts mandated limited practices during certain times of the day. They required practice days without full pads so that athletes could acclimate to the weather. Other states struggled to make changes to protect athletes. As of 2018, one state representative is still struggling to pass a bill that would require head coaches and assistant coaches of interscholastic or intramural sports to complete an education course on heat-related medical issues that could arise from a student athlete’s training.

In 2009 a Kentucky coach faced reckless homicide and wanton-endangerment charges in connection with 15-year-old heat-related death. It was alleged that his players were in full gear, and several of them were denied water and told to keep running wind sprints — called “gassers” — in 94-degree heat, even after vomiting. It was learned that the boy who died was taking amphetamine Adderall for an attention deficit disorder, which affects the body’s ability to thermal regulate. A jury acquitted the coach in two hours, but yet another lesson was learned at the expense of a young boy.

In 2011 two football players and one coach died after practice in scorching temperatures.

Education and hydration are the answer to ZERO deaths from heatstroke.

Stopping heatstroke deaths takes a combination of adequate hydration and coaches that understand the causes and symptoms of heatstroke.

The 1960s were the beginning of the educational process that continues. The learning curve to eliminate heat stroke still costs the lives of many boys. In 1962 we learned that the new plastic shoulder pads did not allow air ventilation and was the primary suspect in the deaths of Mike and Reggie. In 2009 we learned that prescription amphetamines combined with a strenuous workout, could precipitate a heatstroke death. In the decade of the 2000s, the death rate due to heatstroke rose for the first time in 40 years. One of the reasons is now due to the enormous size of the high school athletes. Doctors state that their weight is more fat than muscle, and even if this athlete is hydrated, fat makes it harder for the body to dissipate heat and could cause heatstroke. Quite frankly, if Joe Good had played ball in 2018 instead of 1961, he may still have died.

Research At the college level based on an ANNUAL SURVEY OF FOOTBALL INJURY RESEARCH from 1931 – 2014 by Kristen L. Kucera, MSPH, Ph.D., ATC Director, National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill the worst decades for heatstroke were in the ’60s and ’70s.

1960’s- 42 deaths 1970’s – 31 deaths 1980’s – 14 deaths 1990’s – 14 deaths 2000’s – 29 deaths

From my perspective, 56 years after Reggie’s death and Bill Littles’s positive comment that Reggie’s death meant that thousands and thousands have lived and Out of tragedy, he gave us all a gift” is still valid but somewhat tainted by the lessons not learned. From my perspective, it is inexcusable for one athlete to die from heatstroke in 2019. Shame on any system that knows the causes of heatstroke, but refuses to follow protocol to prevent it. Until the system becomes more disciplined and educated, more preventable deaths of young boys will continue, and their families will suffer the consequences.

Billy Dale- Proud member of the 1967 football recruiting class.

Comments

Mark Walters was a trainer for Augie Garrido:

Billy,

I really enjoyed your article, and as we approach the summer months, the importance of keeping well hydrated has not always been in the forethought of our coaches in years past. The mid-60s was in an interesting time in sports science, where you had your traditional old school coaches like Royal, Bear Bryant, and Woody Hayes who kept with the tried and true coaching philosophy of no pain, no gain; going against advances in sports-science. The coaching models of the time often butted heads with sport-scientists who wanted to introduce medical based training models with the old guard but were often rebutted.

Where hydration is concerned, one of the forefathers is Robert Cade, a San Antonio native, and UT grad and medical school grad. Cade went on to become a professor at the University of Florida, and after doing research about dehydration with members of the Florida football team, he became a founding inventor of a product called Gatorade.

UT does a great deal of research in the field of sports-science. Where Gatorade is a high carbohydrate drink, Dr. Lisa Ferguson-Stegall at UT recently published a paper on a low-carb beverage with added protein that increases endurance times in cyclists. Dr. John Ivy, one of the nations top researchers has pioneered our understanding of muscle metabolism and how nutritional supplementation can improve exercise performance, recovery and training adaptation. Where at one time there may have been a divisive line between coaches and those outside the direct control of the program, today there is a co-joined relationship that feeds off one another to make sure that the best product is put on the field every Saturday in the fall.

J