2000’s Football T-ring Reflections

Roy Miller 2005- 2009

ALL ROADS LEAD THROUGH MACK BROWN

ALL ROADS LEAD THROUGH MACK BROWN

As a boy living in Virginia, he loved the ACC, particularly Mack Browns and North Carolina’s Tar Heels. A decade later, destiny called, and Roy got his wish to play for Mack Brown as a Longhorn. However, the road to signing with Texas was enigmatic.

During his recruitment, Roy visited Texas, UCLA, Baylor, the University of Utah, and the University of Oklahoma. In his Sophomore year of high school, he committed to O.U. One of the main reasons behind his decision was his mentor, Tommie Harris, who achieved success in all levels of football. Tommie’s parents had taken Roy to several O.U. games in the past.

Roy believed that the recruiting process was finished, but it turned out that it wasn’t. When the Oklahoma staff visited Roy’s family, the Millers felt slighted. Upon informing his Sooner recruiting coach about this, the coach said Oklahoma would “win with or without” Roy.

At that moment, Roy realized something was missing at O.U. According to Roy, “it didn’t really feel like a family” there. So, he decided to attend “Junior Day” at Texas. It was at this recruiting event that Roy discovered a real family environment. Roy said that Mack Brown did an excellent job selling the Longhorn culture. He laid out the rich tradition and rich history of the Texas Longhorns. Each member of the team did not want to let his teammates down.

Afterward, O.U. pressured him to stay true to his commitment in ways only coaches whose livelihood depends on getting 5-star recruits can do. Roy felt disrespected by the pressure he endured, and he told O.U. that he would reopen the recruiting process and consider Texas.

The rest is history- Roy signed with Colt McCoy, Jamaal Charles, Henry Melton, Jermichael Finley, Roddrick Muckelroy, and Chris Hill. Roy was at Texas for one national championship and the 2008 team that almost made it to the national championship game.

Roy Miller attended the University of Texas at Austin from 2005-2008.

The Horns treated him much better, so after the US Army All-American game, Miller chose the Texas Longhorns. Coach Mack Brown and Gene Chizik made Miller the top priority of their recruiting class. In fact, Coach Mack Brown visited Killeen Shoemaker High School to visit Miller and greeted every single teacher in the building. Considering the massive popularity of football in Texas, Coach Mack Brown was regarded with more importance than even the Governor of Texas.

Being a University of Texas’ alumni, Miller has been an All-Conference player, Big 12 Conference champion, Big Twelve Player of the Week, a National Football champion, and The Fiesta Bowl’s most valuable player on defense. Miller finished his Longhorn career playing in 49 games and starting in 19.

Quan Cosby the Road Less Traveled

Quan, like many Texas football players, didn’t dream of becoming a Longhorn when he was younger. He wanted to be like the exciting Auburn and Florida State players, Bo Jackson and Deon Sanders. Quan admits that he only watched one school, and that was Florida State. However, everything changed for him when Mack Brown became the coach, and Chis Simms hosted him during his visit to Texas.

In 2001, Cosby was close to signing with Texas and becoming a part of a class that included many future NFL stars. However, he decided to pursue his love for baseball and turned down the scholarship. Money was the driving factor behind his decision. After spending four years in professional baseball, he realized he wanted to return to football and become a scholarship college athlete. At the age of 23, he started over from scratch. Cosby was a part of the 2005 Longhorn recruiting class, alongside great athletes such as Colt, Jamaal Charles, and Henry Melton. Cosby even shared an apartment with Jamaal Charles. A couple of years later, both McCoy and Cosby were breaking records.

As a senior in 2008, Quan set some impressive records by catching 92 passes for 1,123 yards and ten touchdowns. By the time he left Texas, he had become the second-leading receiver in career receptions with 212, third in career receiving yards with 2,598, and fourth in touchdowns with 19. His 4,701 all-purpose yards also earned him the #6 spot in Longhorn sports history. Despite his impressive accomplishments, Quan’s major regret is that his eligibility was up, and he could not play on the 2009 national championship contender.

Texas Football: Former Horn Nate Boyer featured in Super Bowl commercial February 2nd 2020 article on “Hook’em Headlines” written by Andrew Miller @andrewmillerssc

BY CHRIS O’CONNELL IN NOV | DEC 2020, TXEX ON NOVEMBER 2, 2020 AT 8:00 AM | NO COMMENTS

A former member of the Texas football program was featured in a Super Bowl commercial during a game where many alumni from the university are participating in Miami’s festivities on Feb. 2.

Former Texas long snapper Nate Boyer was featured in a Super Bowl commercial for YouTube. YouTube had several commercials early on in Super Bowl LIV, but Boyer was the first ahead of kickoff. The commercial briefly covered Boyer’s journey with the Texas Longhorns football program, where he learned about the game and worked his way up to become the starting long snapper for the team.

Boyer played four years on the Forty Acres, three of which he was a starting long snapper. He was also an honoree of the All-Big 12 Academic First-Team. Boyer also won the Big 12 Sportsperson of the Year award in 2013. He was the third former Longhorn to get such an honor. In 2013, he was also the first winner of the Armed Forces Merit Award.

Moreover, Boyer played for the Longhorns from 2010-2014. He was then on the roster for one year with the Seattle Seahawks in the NFL in 2015. The Seahawks released Boyer after signing him to a free agent contract following the 2015 NFL Draft. He played in three preseason games with the Seahawks. That was about the end of the NFL career for Boyer.

Boyer was also featured in the ESPN documentary “The Long Shot” within the last two years.

A member of the US Army and a Texas Ex, Boyer did about as much as possible to make the best impact on and off the field. He’s the definition of a hard worker, grinder, and a hero off the field for his service to the country.

Texas can be more than proud of what Boyer accomplished during his time at the Forty Acres and in the US Army. The attention that he’s earned since his football career ended is well-deserved, and it’s nice to see his story featured during the Super Bowl.

Nate Boyer by Tim Taylor 11/13/2021

Nate Boyer is a name that is familiar to almost all Texas football fans. Nate’s story is a testament to perseverance and commitment, and thanks to Billy Dale of the Texas Legacy Support Network, I was able to interview Nate in September in anticipation of this week’s newsletter.

My first question was, Why did you choose the University of Texas? Nate said that it was a good public school, that he loved Austin, and that Texas had a great football tradition. He also noted that Texas is very good for veterans. Nate had joined the Army after serving as a relief worker in Sudan, building refugee camps. Boyer enlisted in 2005, and he became a Green Beret in December 2006. His service included tours in Iraq and Afghanistan.

During a break from the Army, Nate attended summer training camp on The 40 Acres in 2009. He met Coach Mad Dog Madden and Coach Ken Rucker, and both encouraged Nate to give playing football a shot. Upon completing his Army career, he applied to and was accepted at the University of Texas at Austin. He walked on to the football team, even though he had never played football. He was a 29-year-old redshirt freshman, but he stuck with the team. His hard work earned him the starting job as the Longhorn deep snapper, a position he held for 3 years, playing in 38 consecutive games. After playing at Texas, Nate got a shot to play for the Seattle Seahawks. While he didn’t make the team, he made some great connections, which would lead to the next phase of his life, one focused on service. Nate became involved in several notable charities.

The first is called Waterboys, which Chris Long started. Chris Long, Nate, and others bring together veterans and NFL alumni to go to Africa and climb Mount Kilimanjaro to raise money, which funds the drilling and development of water wells in Africa. The climb symbolizes the many miles so many African women must walk every day to find clean water for their families. So far Nate, Chris, and Waterboys have raised money to build 32 water wells in Africa. As Nate pointed out, clean water is the key to improving life and he said that when a well goes in, a school soon follows.

Nate Boyer teamed up with FOX Sports NFL Insider Jay Blazer to found MVP: Merging Vets & Players. This organization pairs combat veterans and professional athletes in seven cities, bring them together in open forums to discuss the challenges and issues they face, creating a great network and support group built around peer-to-peer counseling and establishing mentoring relationships

When I talked to Nate Boyer in September, Texas was two and one, coming off the Rice win and getting ready for Tech. At that time, we were all expecting a really great season for the Longhorns. Looking back, it is interesting that I asked Nate what he would like to pass along to the readers of this newsletter, and he said, “to keep the faith and stay loyal, to the University and each other.”

That’s a pretty good message no matter the time or place, but given Texas’s tough four-game losing streak, it is especially important. We do you need to keep the faith, stay loyal to The University of Texas, and be patient and supportive of Coach Sarkisian and his staff as they toil to rebuild the great Texas Longhorns football program. A program that attracted an American war hero and gave him the chance to play football, leading to a national platform which he now uses to help so many people.

My thanks to Nate for his time. And my thanks to each of you who take the time to click on the links above and support Waterboys and MVP.

And again my thanks to Billy Dale for arranging the interview. The breadth and depth of the stories and articles and the amazing photos on the TLSN website is astounding, and I encourage you to sign-up for the newsletter and to support the organization.

On YouTube, there is a highlights package featuring key plays from Texas linebacker Robert Killebrew’s career, sound-tracked by “Last Resort” by Papa Roach. Across the three-plus minutes of mid-aughts, pre-HD footage, Killebrew is a bulldozer, plowing into quarterbacks, demolishing punt-protection units, and stopping ball carriers in their tracks. As violent as football is already, Killebrew, BS ’07, who played outside linebacker for the Longhorns from 2005-07, seems to be playing a different, more intense version of the game. The only knock on his playing was that he sometimes craved that contact too much, to the tune of 15-yard personal foul penalties.

This portrait is wholly incongruous with the Robert Killebrew of today. Instead of being famous for taking running backs apart, he puts them back together, increasing their mobility after injury and reducing pain. Killebrew is a renowned physical therapist in Central Texas who works with NFL players, NBA athletes, cheerleaders, professional baseball players, and MMA fighters, among his list of almost 50 weekly clients.

Lots of college football players find a new career path when the glory days of the gridiron are over. But they are still, unmistakably, football players. While Killebrew brings a certain intensity to his current occupation, he is different than most veterans of the sport in that he knew exactly when to walk away.

“It’s when I realized I had more to offer the world than just my body and my ability to hit people hard,” he says on a video call in June, at the end of a long day before going home to his wife and two young daughters. “I was not good enough as a football player, but I was good enough as Robert. I had to dissociate between the two.”

Killebrew grew up in Southern California, the son of a pastor at a church in Compton. At age 10, the family moved to Spring, Texas, and in junior high, someone asked him if he’d like to play football. Unfamiliar with the sport, he says he was terrible at first.

“I was on the C-team,” he says. “Not even the B-team. I told my counselor that I wanted to quit, and she said she’d take me out of athletics.”

But the counselor went a different route. She called Killebrew’s mother, who responded that she didn’t raise quitters. In quick succession, players got hurt, and he was moved up to the B-team, then up to the A-team, and he started to get on the field in key situations. He had to work to stay on the field, so by age 13, he was waking up at 6 a.m. to run, lift weights, and set up homemade drills in the backyard.

“I was horrible,” Killebrew says, “but I worked at it.”

By high school, Killebrew was a force at the defensive end. In his junior year, his coach told him he had a note in his locker. He thought he was in trouble. It was from Oklahoma head coach Bob Stoops, who was there to meet him.

“He told me, ‘I think you can go to college off this,’ shook my hand and left. I didn’t even know this was a possibility. I was playing this to have fun with my friends and beat up on some people,” Killebrew says. By the end of high school, he had 60 offers and his pick of anywhere he wanted to go.

He chose Texas for three reasons: academics, the competition at his position, and to be close to his family.

It felt like starting all over again once he got to the Forty Acres. He couldn’t crack the depth chart as a redshirt freshman, even as a highly touted recruit, because in his new position of outside linebacker, he sat behind one of the best defenders in the nation: Derrick Johnson. One practice, his position coach told him that they wasted a scholarship on him. Instead of shriveling, he just worked harder.

Killebrew eventually got on the field and never relinquished his starting role. Teammates, especially fellow defenders like safety Ishie Oduegwu, BS ’10, gravitated to him because of his intensity and leadership on the field and his approachability off it.

“Being violent, we shared that tenacity, that nature. But he was always cool, leading by example, being a positive force,” Oduegwu says. “I looked to him like a mentor … actually just more like a big brother.”

He won a national championship at Texas, and with his work ethic and natural talent, it appeared he’d be continuing his career in the pros. Life had other plans.

“I got picked up in a limo with Champagne and got dropped off on a school bus with a sack lunch. I thought I had made it. On the way home, I thought, This is how they did your boy.”

Last November, Killebrew joined the staff of Austin Physical Therapy, started by former Texas Longhorns trainer Cullen Nigrini, MEd ’04, who treated Killebrew during his playing days on the Forty Acres. It was a partnership they couldn’t have foreseen 15 years ago, especially because Killebrew had an arduous journey to his new path once he graduated.

After failing to make the NFL after tryouts with the Bears, Texans, and Seahawks, Killebrew retreated to Southern California with his college sweetheart (now wife) Kristin, whom he met while he played for Texas and she was a member of Texas Pom. In California, he became, in his words, “a surf bum,” working construction to make ends meet. That’s when the Calgary Stampeders of the CFL called. Soon after reaching Alberta, Canada, he realized that he had come to the end of his playing days. He looked in the mirror one day and said, “You’re not good enough.” That’s a difficult bit of self-awareness for a hulking national champion, a looming figure who quarterbacks saw in their nightmares. But once he realized his life didn’t have to end when the final whistle blew, he felt free. After a hamstring injury, the team let him go. He took the rejection as a positive omen.

“What we see as failures might be things saving us,” Killebrew says. “The way I played I am 100 percent confident I would have had CTE, if I already don’t have it.”

His father, in addition to being a pastor, was also an occupational therapist, which gave Killebrew an idea. He moved back to Texas and applied to the physical therapy program at Texas State. Once again, he was told he wasn’t good enough.

“They looked at my transcript and started laughing,” Killebrew says. He enrolled at Austin Community College for two years, working as a hospital tech on the side. He would wake up at 5 a.m., work until 2 p.m., attend class from 3-7 p.m., and study until midnight every day.

“It was a lot,” Killebrew says, pausing to collect himself. “I remember the [Texas State administrator’s] voice in my head, his face, every morning, getting up, working, learning, studying in between.”

Killebrew got straight A’s, took the GRE, and applied again to Texas State. He was once again turned away. A California school called St. Augustine opened a campus in Austin, so Killebrew took his transcript there, and was told to get his GRE score up and try again in another year. He waited, re-applied, and was put on the waitlist.

“That was a huge success to me—foot in the door,” he says. Shortly after, he was admitted. He was overwhelmed by how difficult and competitive PT school was, but he gutted it out, and after graduating with his doctor of physical therapy degree, he got in touch with former Texas running back Jeremy Hills, who had started a successful personal training business. He asked Hills if he could work with his clients as they trained for the NFL Combine, pro bono. That led to a business partnership and friendship that continues to this day—Killebrew gets athletes ready to take the field and Hills trains them.

“He’s my No. 1 source. I trust him with any athlete I work with,” Hills says. “The protocol is, before they work with me, they have to get cleared by him.”

At UT, Nigrini says, “Robert was known as an intense worker, in the weight room and on the field. He was full speed in everything he did.” Nigrini says that Killebrew brings that intensity to physical therapy every day. When Killebrew started at APT in November, Nigrini’s goal was to have his new hire eventually work with 40 clients per week. Within a few months, Killebrew was already averaging 45.

“People love what he is doing,” Nigrini says. “It wasn’t because of the internet or marketing. It was because he was doing good work.”

While Killebrew put his heart and soul into becoming the best linebacker he could be, he says he loves his new life. Besides, he still gets to connect with athletes like himself, aided by that tenacity he fostered and the credibility he brings to the job as a guy who has been there before.

“And I’m not in a cubicle,” he says, smiling. “I get to help people get better. I’m a servant. I couldn’t be happier.”

Chris Simms

There is nothing good about trying to be perfect. Perfection only leads to a sense of failure.

STEER CRAZY CHRIS SIMMS IS ALL FOOTBALL, ALL THE TIME IN HIS FERVENT QUEST TO QUARTERBACK THE LONGHORNS TO A NATIONAL TITLE AND FIND HIS PLACE IN TEXAS FOOTBALL LORE

By Austin Murphy

August 13, 2001

Below is a paraphrased article in Sports Illustrated dated August 2001. I have added my thoughts on Austin Murphy’s great article about Chris Simms in bold black font.

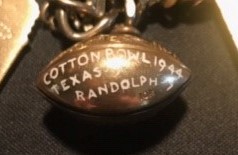

From Wikipedia -He spent his freshman year as the backup to Major Applewhite and saw limited playing time until the end of the season. Going into the Texas A&M game (the so-called Bonfire Game as it followed the tragic death of 12 students during the construction of A&M’s annual bonfire), Texas was ranked #5, but right before that game, Applewhite got an intestinal virus that kept him up all night and required him to be put on an IV the next day. As a result, Simms got his first career start and had the Longhorns up 16–6 at halftime. After Simms struggled in the 2nd half with Texas still ahead, he was replaced by Applewhite in the 4th quarter. Still, Applewhite could not get Texas any points, they fell behind in the last 6 minutes, and Applewhite fumbled on their last possession. Simms took over again during the Cotton Bowl when Applewhite suffered a knee injury in the 4th quarter.

The next year Simms gets his first start as a Longhorn and throws an interception returned for a touchdown. Coach Brown then replaces Simms with the record setting Applewhite. Over the next three games the quarterbacks split time, but Chris is officially demoted to the second team after the OU game. Four weeks later, Applewhite sprains his right knee against Texas Tech and enters the game, and his struggles continue. Against Kansas the next week, he throws another interception that is returned for a touchdown. Leaving the field after the interception, he returns to the sideline and says to Brown, “Can you believe that?” With Applewhite on crutches, Simms knew he could screw up royally and not get the hook. So he relaxed and played his best football of the season, leading the Longhorns to a 51-16 rout. Two weeks later, with his confidence soaring, Simms completes 16 of 24 passes for 383 yards, three touchdowns, and no interceptions in a 43-17 win over Texas A&M. For the first time in two years at Texas, he’d lived up to his billing. The Golden Boy was golden. “I wasn’t golden,” he corrects. “I was pretty good.”

What happened to change his attitude?

Austin Murphy with Sports illustrated says, “Chris Simms was trying to meet his own self-inflicted expectations.” His roommate Babers recalls a conversation with Simms and Scaife, the tight end. “We were talking about the NFL, talking about cars and houses and stuff. Chris asked Babers, ‘Do you want to be the best corner ever?’ I told him, ‘To be honest, no. I just want to play in the league, make a little money, take care of my family.’ Chris says, ‘I wouldn’t waste my time playing if I didn’t want to be the best ever.” Babers responds to the reporter, “It’s crazy how high he’s set the bar for himself.”

#1 Chris Simms

For the most part, however, Simms was trying too hard to make a big play–“forcing the ball into cracks,” says Davis, the offensive coordinator. Adds Babers, “He knew if he didn’t move the team in two series, one of the best quarterbacks in college football (Major Applewhite) was waiting in the wings.”

Psychologists say Living life with a fear of failing usually thwarts an individual’s mental and social development and reduces their quality of life by extension. Athletes who are not happy with a score assessed by the position coach after a game of 9.9999 instead of 10.0 are setting themselves up for a miserable and pressure-filled life.

There is self-awareness in Simms, and he finally adjusts his thinking from wanting to be the best athlete ever to an athlete able to control his negative impulses when he is imperfect. This new perspective helped Chris perform with less anxiety and more self-confidence during competition.

Here are Chris Simms Longhorn records.

Texas – Most Touchdowns, Season (26), tied by Vince Young in 2005, surpassed by Colt McCoy in 2006

-

Texas – Most Touchdowns, Game (5) tied with James Brown, surpassed by McCoy in 2006

-

Texas – Most 400-yard passing games, Season (1), tied with Major Applewhite and McCoy

-

Texas –Most 400-yard total offense games, Season (1), tied with Applewhite, surpassed by Young

-

Texas – Most 400-yard total offense games, Career (1), tied with Applewhite, surpassed by Young

-

Texas – Passer Rating, Career (138.4), surpassed by McCoy 2009

Adam Ulatoski

#74 Adam Ulatoski is a Longhorn benchmark. Adam has proven to be a team player both in sports and in his professional life. As a Longhorn football player, he was nominated by his teammates three years in a row as the most “Tenacious” player on the team. A moniker earned the hard way through a herniated disc, back ailments, elbow injuries, and knee complications.

Adam’s last year as a Longhorn was in 2009. We met each other in 2015 over coffee. As we shared football experiences, I had this feeling there was something exceptional about Adam, but I could not articulate my intuition. On June 5, 2018, Adam and I met again for breakfast, and the answer I could not articulate in 2015 was now very apparent. Adam Ulatoski owns a special place in the history of Longhorn football. Including his 2005 Redshirt year, Adam is one of Texas’s only players to share workouts with two of the best quarterbacks in UT history -Vince Young and Colt McCoy. He is also one of the only Longhorn players that participated in the best 5-year record ever in Texas football with a 57-8 won-loss record. Adam has come closer to being part of three national championship games than any player in Longhorn football’s history. In 2008, the last play of the game (Texas Tech) ruined a Longhorn National Championship bid, but history honors Adam for two journeys to the National Championship game- As a redshirt against USC and a starter against Alabama.

COLT McCOY

In the book “The Road to Texas” by Mike Roach, Longhorn receiver Quan Cosby speaks about Colt McCoy, stating that he was the least likely person to take the reins and continue the Longhorn legacy. Jevan Snead seemed to be the better of the two recruits and was destined to replace Vince Young. However, history was on Colt’s side. He worked hard, and Coach Davis changed the offense to exploit Colt’s running and passing abilities in the spread offense.

Colt wrote the article below for The Players Tribune. The full article is in the link below, and the text has been saved just in case the link is lost. Billy Dale has added the images to add dimension and reference to Colt’s article.

QUARTERBACK / WASHINGTON REDSKINS

Dear Horns,

While I was playing at Texas, I had this little tradition to get my head right before a big game.

As the team went out for the coin toss, I would find a place on the sidelines where I was alone, take a knee, and for a few moments, I’d just be present in my surroundings. I’d look at all the fans in the stands. I’d look at the band all dressed up and jumping around. I’d take a few moments to thank God for the opportunity in front of me. And then I’d look at my teammates, all of them standing there with this focused intensity, ready to compete. I’d take a mental picture of everything happening and feel this tremendous sense of joy and pride to be there in that moment, as part of this thing that is so much bigger than me.

Once I took that time to acknowledge what was going on around me, my focus shifted entirely to my job and what I had to do. The noise from the crowd and the band became secondary. I didn’t get swept up in my emotions or the setting. For the next three hours, it was all about executing what I had prepared for that week – and my entire life up to that point, really.

Even though I was prepared, it was never easy. It’s been a few years since I suited up in burnt orange, but I still remember the nerves I felt leading up to the big games. I especially remember how tough it was to deal with them as a younger player, like many of you are.

My second collegiate start came when I was just a redshirt freshman playing against the #1 ranked Ohio State. We’d just gone undefeated and won a national championship, and the expectations couldn’t have been any higher on myself and our team. What I remember maybe even more than the game itself was the pressure I felt beforehand. It was just nuts. In the months leading up to kickoff, that game was all people could talk about. It was brought up during every conversation I had, whether it was with a student, professor, or the waiter taking my order at Trudy’s. I felt overwhelmed. I was only a 19-year-old kid from a town with a population that wasn’t big enough to fill up a single section of our stadium, but I somehow found myself in control of this thing that meant so much to so many people. I didn’t know how to deal with it.

But here’s the thing I learned eventually: The pressure doesn’t go away. It’s always there. You’re at Texas — the expectations never ease up. So what I discovered over time (and what you will as well) is that pressure is a good thing. Eventually, I learned to feed off of it. I even craved it because it pushed me to be the best version of myself.

Now I feel for you guys as Notre Dame comes to town because I remember how long it took for me to develop that mindset. I was lucky enough to be in school before social media blew up the way it has. I’m sure you have plenty of people telling you how great and terrible you are at all times as soon as you open your phone. Try to shut off that noise. Regardless of how much pressure you feel heading into Sunday, remember that the only thing you’re entirely in control of is your performance. I’m telling you now what it took me years to learn and accept: If you go out there and play to the very best of your ability, that’s all you can ask of yourself. And more times than not, it will be enough to win.

I’m entering my 7th season in the NFL, and when I look back on my college days, sometimes I think about some bad plays I made or ones I wish I could have back. But most of all, when I look back on my time as a Longhorn, what I remember most is just how fun winning was. I remember listening to Coach Brown’s postgame speech after a big victory, and then the entire team singing “Texas Fight!” together at the top of our lungs. I remember that feeling of walking to class with my teammates and having everybody we passed throw up their horns and congratulate us. I distinctly remember the pride I felt, but also the pride other people felt because of our performance. When we won, we lifted up the entire campus. And I remember wanting to have that feeling all the time. Our entire team did. I wanted to win for our school, I wanted to win for our coaches, and I wanted for my teammates. That was part of what made us great.

The work to achieve that winning feeling never stopped. Every day of practice was a legit competition. We used each other’s talent as a resource to get better. I was out there trying to throw against the likes of Earl Thomas, Aaron Williams, Michael Griffin, and Aaron Ross — guys who would go on not to just play in the NFL but become very good NFL players. The practice was so difficult that the games were just fun because we finally got to unleash all that competitive energy we built upon some other team.

When we won, we lifted up the entire campus. And I remember wanting to have that feeling all the time. Our entire team did.

As time went on, we all felt like we grew together. We wanted to see each other get drafted and achieve our dreams, and we all pushed each other to get to that point. Those bonds never break. To this day, I love checking in with my old teammates and talking about old times.

We reminisce about bowl games, 45-35, and the great run in ’08-‘09 when we only lost one game. We laugh about things that happened in the locker room and the dorms. And we thank each other, even without directly saying it, for being a vital part of the period of our lives when we became men.

Someday, many years from now, maybe you guys will get together and look back on your time at Texas. And you’ll reminisce about some disappointments from last season when you lost some close games but won some big ones. Then you’ll remember that season opener against Notre Dame when you all realized just how talented you were and showcased it in front of the entire nation. You’ll look back and take pride in how you lifted Texas football out of the lean years and defined a new era of greatness. In some ways, I’m jealous of you. You have so many memories just waiting to be made.

I’ve gotten to know Coach Strong, and I really believe in what he’s building. He values the same things that helped Mack Brown make this program great – a strong belief in family, close relationships with his players, and a deep love for this University. When I was in school, I felt so proud to play for Coach Brown, and I can see that Coach Strong has instilled a similar pride in all of you.

I like where our program is right now. I really do. I had the opportunity to work out with a few of you this summer, and it made me feel even better about the team. The talent is there. I see flashes of the same greatness that I was fortunate to be around while I was on campus. Yes, people have been frustrated with the results the last couple of years — and rightly so. But if you look closely, you can see that we’re turning a corner. You have the opportunity to erase a lot of bad memories for every person who feels a little bit of pride when they see burnt orange.

You have the opportunity to erase a lot of bad memories for every person who feels a little bit of pride when they see burnt orange.

I don’t need to tell you that Notre Dame is good. You saw that last year, and I’m sure you’ve heard about how good they are just about every day since then.

But on Sunday, last year won’t matter. Not one lick. Your record right now is 0-0. Everything is ahead of you.

Trust that your coaches are going to have you prepared. Trust your reads and your instincts. These games are why you were recruited to play here, so don’t try to be a superhuman version of yourself. Be the player you know that you are. You made it to Texas because you’ve played very well in a lot of games throughout your lifetime. This is just another opportunity to showcase what you were born to do.

Before kickoff on Sunday, find a quiet place on the sideline. Take a knee and look around the stadium. Breathe in the air and appreciate the atmosphere. And take a moment to collect your thoughts, say a little prayer and remember how blessed you are to be playing the greatest game on earth at the greatest school.

Then get on your feet, strap on your helmet and go show those boys how we play ball in Texas.

Hook’em,

Colt

Michael Huff – A Michigan Wolverine turned Longhorn

It was all Michigan all the time in the Huff family. When Michigan played the family gathered to support the Wolverines. The family never watched Texas football in Michael’s formative years.

According to the book “The Road to Texas” by Mike Roach Michael Huff had two scholarship offers for track from the University of Houston and Arkansas and only one football scholarship offer from Purdue. Texas offered a scholarship late in the recruiting process. He visited Texas in December after his last high school football game. Mack Brown offered him a scholarship as a “developmental prospect”. A two-star athlete. Since Michael had few football scholarship offers, he committed immediately. His family was shocked that he received a football instead of a track scholarship.

Michael demonstrated exceptional speed and mental toughness as a Longhorn, starting in 50 out of 51 games. Throughout his career, he achieved numerous milestones, including recording seven interceptions – 4 of which were returned for touchdowns, setting a school record. In addition, he made 318 tackles, had 44 pass break-ups, forced six fumbles, and made three recoveries.

Michael wrote the article below for The Players Tribune. The full article is in the link below, and the text has been saved just in case the link is lost. In the USC game, it was Michael who stopped USC’s White short of first down, which led to Texas’s touchdown to win the game. Michael had double digit tackles, one important game changing tackle, and one fumble recovery and was named Defensive player of the game.

QUALITY CONTROL COACH / UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN

When Texas is playing good football, it just seems like the world is a better place.

It’s hard to describe exactly. It’s almost like there’s this warm feeling all throughout campus, Austin, central Texas, and the entire state. There’s a definite buzz of positivity. The grass is greener, everyone is happier and sweet tea just tastes that much sweeter.

You hear plenty of theories around the state about why the Longhorns suddenly stopped winning a few years back. It’s been analyzed and reanalyzed up and down by every person who has an opinion about football. But I think that, ultimately, none of it really matters. I’m not here to discuss what went wrong, or whether “Texas is back.”

What I do want to talk about is what this program means to me — because it means a lot. It means just about everything.

I was fortunate to spend eight years playing defensive back in the NFL. It’s something I’m very proud of and that I’ll always be thankful for, but — and I tell this to every young man I meet who has similar ambitions — it was a job. From the moment you’re drafted to the day you retire, there is always a business element attached to playing in the league. Even though you spend your whole life dreaming of making it there, a lot of things become much more complicated once you’re in the NFL. From the outside, you only see the money, the nice houses, the flashy cars and the endorsements. But once you’re immersed in the actual pressures of the job — the injuries, the benchings, and the reality that, at any moment, your career could be over — your perspective changes just a bit. Your relationship with the game changes.

In college, things were a lot simpler. It didn’t matter whether you were a five-star blue chip, or a two-star guy like myself — everyone was treated the exact same. You slept in the same dorms, ate the same food and were held to the same standards. The coaches might have made the decisions in terms of scheme and playing time, but it was the guys you lived with — and grew up with — who you really answered to.

When I close my eyes and think back to that time in my life, the first image that pops into my mind is the DB room. Oh man, the hours I spent in that room. I can see Quentin Jammer right there at the front, quietly watching film. When I was just a redshirt freshman, he was one of the guys I looked up to. He was also the person I never wanted to disappoint.

Duane Akina

Fans and the media often focus on (and blame) college coaches, but what is often overlooked is how crucial veteran leadership is to players’ growth.

Yeah, if I ever screwed up during a game, I knew Duane Akina, our DB coach we give me an earful. Longhorn player Rod Babers said

Akina was a coaching intellectual.

“Coach Akina was a new-age coach who really wanted to break us down mentally and intellectually. As a true teacher, he wanted to find out how we best learned the concepts.”

Huff continues, But during those practices and games, it was guys like Quentin I didn’t really want to let down. If I was supposed to be behind the line before we started a drill, I knew I better make sure I was behind that line or otherwise those seniors would be all over me. We all knew what we expected out of each other — and it was that standard that led to us producing the best defensive backs in the country for the better part of a decade.

When I first enrolled at Texas in 2001, I was a track guy. I liked looking pretty in my uniform and grabbing interceptions. But tackling? That wasn’t for me. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was a pretty selfish, one-dimensional player.

Four years later, I was a starter on an undefeated team playing in its second consecutive Rose Bowl. The final play of my career, it was fourth-and-two with USC leading us 38-33 late in the fourth quarter. The Trojans were on our 45-yard line and we needed to prevent them from getting a first down in order to keep our national championship hopes alive. When the ball was snapped, they handed it off to LenDale White, one of the most physical running backs in the country. And with the help Brian Robison, Tim Crowder, Rod Wright and the other guys up front doing the dirty work, I got an open shot at LenDale and stopped him just short of the chains.

And I think most college football fans know what happened from there.

That was a play I couldn’t have made when I first arrived at Texas. Not just physically, but I also wouldn’t have had the aggressive attitude andinner fire to do that. That play was possible because of a lot of work that had gone on behind the scenes to mold me as a player and as a person. It was possible because of a mentality ingrained in me that we would not and could not lose.

Over time, I think that edge — that mentality — slowly left our program.

And the biggest reason why I decided to rejoin the Longhorns as a quality control coach last year was to help bring it back.

If you went back to when I was 18 and told me I would be a football coach one day, there’s no chance I would have believed you. To me football was more of a fun game than a life-long career.

But after I retired and was living in Dallas, it felt almost strange not to be involved with the game. I didn’t just miss being around football, I missed being in Austin and with the Longhorns every day. I met my wife there, and we had always dreamed of going back one day. It was Charlie Strong who first encouraged me to get involved with the program. I have him to thank for inviting me back. Then when Tom Herman took over last December, I met with him in his office and we discussed a plan for how I could best help the program. It involves a lot of different things but I was all in and now love what I’m doing.

Here’s what I can say for certain about Coach Herman: You will not find another person more focused or more dedicated to winning. He’s a really smart and detail-oriented person who probably could have found success in a number of fields, but decided to pour his talents intofootball and the young men who play it.

What I appreciate about him most is that he’s a players’ coach. I don’t mean that in the sense that he’s going to love you all the time — what he understands is that that’s not the best thing for every guy. There are a hundred different kids in this program with a hundred different personalities and needs. Tom has shown that he knows that reaching a young person requires a different approach for each kid. And he’s going to find the right buttons to push with each player and you’ll come out of his program as a better player and person than when you arrive. Now that I’m a parent myself, I really appreciate that about him and his staff.

Myself? The younger version of me needed to be pushed and yelled at a bit in order to learn. I remember when we were playing Oklahoma State early in my career, there was a receiver on their team who was talking trash. So after I broke up a pass in a physical manner, I decided to step on his back a little on my way back to the huddle. But I never made it back to the huddle — Mack Brown pulled me off the field immediately and said, in very clear terms, “If you do something like that one more time, you’ll never play here ever again.”

And that was exactly what I needed. I was involved in a lot of plays throughout my college career, but that particular play is the one that makes me feel most embarrassed because I was only thinking about myself. I was happy that I made a play, not that our team had. And that that’s the kind of mentality you can never let exist in a successful program.

As I matured into my junior, senior years I watched how the guys ahead of me operated. And gradually the coaches let me take charge and become a leader. I realize now that if I had maintained that selfish attitude when I became a starter — even if I was really good — it would have eventually been passed down to the guys below me. And that’s a problem that can’t be fixed through schemes or techniques — that’s culture.

A winning culture isn’t something that gets created overnight. It’s much easier to lose than it is to develop. Sometime in the last decade, I think Texas lost that culture of accountability. We became more scared of losing than committed to winning.

That’s what Coach Herman and this staff are changing. Every message is clear, it’s about doing your job, being accountable and playing for the man next to you. I absolutely love what we’re preaching to these kids and the approach the staff takes. It reminds me so much of what Coach Brown built here in the past and in just a few months with Coach Herman, I see it developing again. The culture is changing.

Want to know the worst feeling? The complete opposite feeling of when Texas is playing good football?

Wearing an Oklahoma jersey.

Just awful. Embarrassing. Gross.

There were more times than I care to remember when I was in the NFL that I would lose a bet with a teammate over the Red River Rivalry game and be forced to wear that awful jersey. I had to wear quite a few college jerseys of teams other than Texas during my NFL career. Later on in my career, when Texas started really struggling, it always kind of served as a reminder of how the program was slipping. I remember when I was a sophomore and we only won nine games. It felt like the world was ending. Today, we don’t have a single kid on our roster who has ever won a bowl game. That’s something that seemed unimaginable to me a decade ago.

A big part of my job — the part of my job that I enjoy most — doesn’t have much to do with football. I spend a lot of time with our players just talking about life and my experiences. We’ll grab food or walk to class together, and I get a sense of what their lives are like. Many things are different now than when I was in college. The whole social media phenomenon has made it relatively easy for outside influences to introduce negativity to kids who are at an age when it doesn’t take much to feel negative, as it already is. So that’s a different kind of challenge. But I also recognize that a lot is the same. They have the same hopes and fears as any college kid. Many of the players occupying the DB room today remind me of myself at different phases of my college career. So it’s nice to be able to offer them the advice I think I would have needed when I was their age.

That’s all to say that, in being around these kids, I’ve seen firsthand that they’re doing the right things. I see guys like DeShon Elliott and P.J. Locke, and they’re doing the things that Quentin Jammer and Rod Babers asked of me, and that I passed down to underclassmen. As a coach, as an alum, and as a mentor, that’s really nice to see.

Texas is a huge school with a lot of passionate fans, so the impulse is always going to be to react to a single result and wonder whether the program has returned to its former glory. But that’s just not how it works. What we’re trying to build here — what we had here — took much longer than one game or even one season. Because there’s simply no quick fix for excellence. There’s no one game that’s going to signify that we’re back.

We took a step back in our season-opening loss to Maryland, but we grew from that experience. There are no moral victories, of course, but USC was a real turning point for this young team from a maturity standpoint. Now that we’ve won our first two Big 12 games, we’re heading into OU as a much better team.

The Sooners are the team we’ve all been waiting for. It’s the biggest rivalry in college football, played on a neutral field with the crowd evenly split, all amidst the excitement of the Texas State Fair. We even have a countdown clock in our facility to remind us of this game. It felt like it was so far away for so long, but now it’s just hours away.

Saturday will be a great challenge, as, despite the loss to Iowa State, we still know Oklahoma is an amazing team. It’s an opportunity for us to compete at the highest level and to take a huge step towards getting back where Texas belongs: Among the elite of college football.

Hook ‘Em

Kasey Studdard

Jamaal Charles

BY CHRIS O’CONNELL IN FEATURES, MAY | JUNE 2016, SPORTS ON MAY 2, 2016 AT 8:50 AM

Charles and his daughters Mackenzie (left) and Makaila (right) dance to “Hit the Quan” in the Gymboree below their condo; Ryan Nicholson

Jamaal Charles has it all—money, accolades, a loving family—but he’s still working on immortality.

The mention of melted, yellow, non-denominational cheese in a bowl has Jamaal Charles feeling nostalgic for another time: when he had both of his original knee ligaments, when he ate whatever he wanted, when queso preceded every Tex-Mex meal. Those were the halcyon days.

We’re in Charles’ living room, in Leawood, Kansas, surrounded by his offseason distractions: a pair of DJ turntables and a pile of Playstation controllers. President Obama had just famously visited Torchy’s Tacos in Austin, and Charles is daydreaming of the liquid gold.

“I bet he tore that up,” Charles says, grinning ear-to-ear. “He’d probably like to get that shipped in. Torchy’s, when you gonna let me franchise one out here?”

But that’s all this is now: a dream. If some athletes treat their bodies like temples, on the verge of a comeback from another devastating injury, Charles has decided his is a pristine Buddhist monastery perched atop a mountain. That is to say, no more queso. He’s vegan now.

Six months ago, Charles fell as millions watched. On Oct. 11, after taking a red-zone handoff from his quarterback Alex Smith and cutting back into the Chicago Bears’ defensive line, he tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee. It seemed to spell doom for the Chiefs’ season, their prized offensive weapon writhing in pain on the grass. Instead, a two-headed monster known as the 24-year-old running backs Charcandrick West and Spencer Ware stepped into Charles’ shoes, as Kansas City rattled off 10 straight wins to end the season and earn a spot in the AFC playoffs.

The pain and rehab, the missed playoff games, and the indignity of watching not one but two upstarts prove to be capable replacements for Charles—perhaps rendering him irrelevant—doesn’t seem to phase him on this rainy mid-March day on the Kansas side of the Kansas City suburbs. In fact, he doesn’t seem worried at all.

But the cheerful, four-time Pro-Bowl running back, who is now a revved up, rebuilt machine sitting in front of me, almost walked away from the game. Just four years earlier, he’d torn the ACL in the opposite knee. He’d had enough; he was about to turn 29—the winter of life for a running back—and that last rehab was difficult. He had to take pills to offset the pain he felt getting off the trainer’s table every day during the 2011 offseason. Charles says he was seriously considering retirement.

That seems reasonable enough. He has money: He’s earned $34,162,500 in salary from the Chiefs, according to Spotrac. Judging by the humble accommodations that have been his in-season home for the last six years, most of the eight figures he’s made hasn’t been squandered. He has a beautiful family: a wife, Whitney, whom he met after a track meet his freshman year at UT, and two daughters, Makaila, 5, and Makenzie, 4, born 11 months apart.

Standing on the precipice of either a cushy early retirement or months of rehab followed by the daily grind of punishing helmet-to-helmet hits and the risk of re-injury to his knee, Charles states that he intends to win a Super Bowl with the Chiefs and retire as one of the greatest running backs of all time. And that presupposes him beating out the youngsters to reclaim (and keep) his spot in a now-crowded backfield. In an era when NFL players are retiring early to preserve their future health, why not choose the easy way out?

“One more shot,” he says, much more seriously now, his grin fading. “When I leave I want to be known as Jamaal Charles, phenomenal football player, inspiring to kids and adults. I’m going to take advantage of this one more shot.”

His entire life, scouts have tagged Charles with the same pejoratives: undersized, limited, not particularly physical. Those words are, in the parlance of the hyper-masculine world of football, euphemistic for one word: weak.

The man facing me in his condominium, shoveling fruit salad from a Styrofoam container into his mouth, is not, in a word, weak. He stands, by my estimate, at just under 6 feet, his arms slender but sinewy under a navy blue Puma T-shirt that falls just above a shiny Louis Vuitton belt that holds up a pair of fitted, faded G-Star jeans. His trademark braids are tied in the back and fall just over his shoulders. He speaks softly, and with a distinct Gulf Coast drawl—not quite typical Texas, and with a dash of Cajun. He dots his sentences with pleasantries like “yes, sir” and “no, ma’am,” and words like “again” contain three syllables instead of two.

With the content of his speech—and his condo—Charles walks a thin line between confidence and demureness, teetering between hubristic aplomb and charming humility. His modest apartment where he typically only lives in during the NFL season is decidedly the inverse of an episode of MTV Cribs, yet there are images of Charles from all phases of his career lining every wall, and an extra one airbrushed in the lining of a navy blazer he eventually puts on. His former Longhorn teammate and roommate Quan Cosby teased him when, after he signed a $28 million contract extension in 2010, he bought a baby blue Lamborghini, to which Charles replied, “I only got one!” He says he doesn’t worry about splitting carries with West and Ware next season as long as it benefits the Chiefs, but also mentions lofty goals, like entering the Pro Football Hall of Fame when he retires, which will require him to shoehorn into his remaining career a couple more prolific seasons. That won’t happen if he’s in a timeshare.

Growing up in Port Arthur, Texas, Charles never anticipated reconciling this type of nuance in his life. Born two days after Christmas in 1986, he was raised by a trio of women in his mother, aunt, and grandmother. Early on, he was diagnosed with a learning disability, due to his difficulties speaking and reading.

Today, Charles lets out a knowing chuckle when he misspeaks. He’s not embarrassed or shy about the fact that, despite being a thoughtful person, the barrier between his brain and his mouth is an obstacle the former hurdler and sprinter has never completely cleared. As a child, it was obviously much worse. He was teased when he was placed in special education in elementary school. That humiliation begat glory when during a trip to the Special Olympics in middle school, he entered a couple events and returned home with a fistful of ribbons.

“I was smoking people,” Charles says. “I got to go home to my mom and tell her I won something. Finally in life I won something.” The trend would continue into high school, where Charles was a track star, winning the 5A state titles in the 110m and 300m hurdles his senior year at Port Arthur Memorial. But it was in football where he really stood out.

Bob West, who was the sports editor of The Port Arthur News from 1972 until his retirement last year, spent his earliest years on the job covering a local running back named Joe Washington. He went on to set every rushing record in the area before a stellar career at Oklahoma and a long NFL life.

“I didn’t expect to ever see a back as good as Joe Washington,” West says, “and I didn’t until Jamaal came along. It was obvious … we’ll see this guy on Sundays.” Charles broke Washington’s local rushing record and committed to UT, where again, his speed and lateral movement immediately set him apart from the competition.

Greg Davis, offensive coordinator at Texas from 1998-2010, says he only needed to watch Charles’ high school tape for a couple minutes before deciding to recruit him. When he showed up at practice in the fall of 2005, it became apparent that the true freshman would be taking handoffs from Vince Young as soon as the season began.

Two or three practices in, still in shorts, Davis says, he told his offensive staff, “We gotta get this guy ready to play. He’s too talented.”

Charles is helped off the field after tearing his ACL during the third quarter on Sunday, Oct. 11, 2015, at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City, Missouri; Keith Myers/TNS via ZUMA Wire

Charles showed up dauntless on the field, with fellow freshman Cosby remembering one of the first conversations with his new roommate centered around his record-breaking high school track and football career back in Port Arthur. Cosby alerted Charles that, at Texas, especially with the program at the height of its powers as it was in 2005, everybody on the field was a potential All-American.

“He never brought it up again,” Cosby says, “and he worked as hard as anybody out there.” Charles earned himself major playing time, splitting carries with Selvin Young and Ramonce Taylor as the Longhorns stunned the college football world en route to a national championship in January 2006.

The most difficult part of being a student-athlete at Texas, especially as a freshman, wasn’t shedding tacklers or picking up the blitz. For Charles, even conducting a simple postgame interview was frightening, and the more playing time he got, the more reporters looked for him after games. It led some, even those who knew him well, to confuse his quietness for slowness.

“I had all those gifts in me,” Charles says. “Most people never saw it.”

Some still don’t. “He probably didn’t finish on the dean’s list, but in terms of football he was on the dean’s list,” Davis says when we speak on the phone. UT-Austin doesn’t have a dean’s list, but on Nov. 21, 2006, three days before Davis, Charles, and the rest of the Longhorns would lose a 12-7 game to Texas A&M, Charles beamed as he learned he was named to the Academic All-Big 12 team.

Charles walks gingerly through the third-floor hallway of his building, and at one point, he almost braces himself on a slick black table. Perhaps sensing I was just behind him—that’d be the “awareness” attribute found in the Madden video games—his hand hovers over but never touches the surface. Confident as he is, only five months removed from knee surgery, that he will reclaim his starting job, lead the Chiefs to a title, and retire a Hall of Famer, the man in front of me still has a ways to go.

But then, Charles says, he’s fought through injuries his entire life: numerous ankle injuries that sidelined him at Texas, shoulder surgery during the 2010 offseason to fix problems dating back to high school, and, of course, the two rebuilt ACLs. Heading into the 2008 NFL draft after his junior season, he’d have to prove he could stay on the field.

Charles was typecast as too small to carry the ball 250 times per season, and his NFL scouting profile listed his negatives as “not a particularly physical back” and a “willing but limited pass blocker.” Still, he ran a 4.38 40-yard dash at the Combine and rushed for more than 1,600 yards his junior season. As the draft began on the evening of April 26, 2008, Charles was sure he’d hear his name called early. Five times Roger Goodell said the name of an NFL team followed by the words, “running back from … “ and five times he made instant millionaires out of people not named Jamaal Charles. The last time it happened that day, part of a string of three running backs drafted in a row, the Titans passed up the chance to reunite Charles and Young in Nashville.

Surely round two would be different. He was better than most of these guys. Two teams plumbed the depths of Conference USA and the Big East, grabbing players from Tulane and Rutgers. When round three rolled around, the Lions, perhaps the worst drafting team of the aughts, whiffed on Charles for a player named Kevin Smith. The Chiefs selected Charles in the middle of the third round with the 73rd pick in the draft.

Charles cried as eight running backs had their names called before him—four of them no longer in the league—while silently locking the teams that doubted him in a vault of revenge, only to be opened once the Chiefs found them on their schedule. Oakland. Carolina. Dallas. Pittsburgh. Tennessee. Chicago. Baltimore. Detroit.

“Every team that passed me up and I play ’em, I’m like … I’m about to kill the day,” Charles says with a smirk. “I’m going to destroy them. I still hold that chip on my shoulder. What you think of me, I’m still better than any running back you have on your team.”

But the experience, Charles says, beyond motivating him, kept him humble. Realizing that most people, even some prolific football players, don’t get $600,000 signing bonuses at 21, he checked himself. “To stay joyful, to stay humble,” he says, “I sucked it up. I took that in.”

Charles spent his rookie year behind Larry Johnson before taking the All-Pro’s job in 2009, rushing for 1,120 yards on only 190 carries. His breakout season was 2010, a year in which Charles came up just 65 yards short of 2,000 total yards from scrimmage, leading the Chiefs to the playoffs and earning himself that substantial contract extension in the process. During a week-two game against the Lions in 2011, Charles tore his left ACL and missed the rest of the year. It looked like the Chiefs had made a mistake, that perhaps Charles was as incapable of staying on the field as many had suggested.

“It was a bump,” Charles says, “but I signed up for this sport.” It was actually a bump up, as the Chiefs running back returned to rush for more than 1,000 yards in each of the next three seasons, including 1,509 in 2012, his career high. In 2013, Charles scored 19 total touchdowns, gained 1,980 yards from scrimmage, and was named first team All-Pro for the second time in his career. He missed only two regular-season games out of the next 53 the Chiefs played after his first ACL surgery, coming to a halt, of course, during the Bears game in 2015.

Charles and I head over to Rye, an upscale fried chicken joint that shares a parking lot with his apartment building, for a change of scenery and a photo shoot. He wonders aloud if the biscuits and gravy are vegan before quickly snapping back to reality.

“Nah, I don’t need to eat.” Charles has a personal chef, of course, and even if the gravy is vegan, those biscuits can only help derail the comeback train.

Heads turn as Charles poses for pictures and shakes hands. As a group of polo-clad, middle-aged men walk in, most notice the only person in the building who has scored five touchdowns in an NFL game. One man in the pack simply doesn’t recognize Charles, or celebrities don’t faze him.

“You just walked past Kansas City royalty,” his friend says to him, shocked.

“I talked to DJ the other day,” Charles says, as we walk the sidewalk outside his building with his daughters. “He got paid.” He’s referring to 33-year-old fellow Longhorn and Chiefs linebacker Derrick Johnson, who, one year after a devastating achilles injury, had an All-Pro season in 2015. A week prior, Johnson inked a new $21 million deal to stay in Kansas City.

“Does DJ’s great comeback season inspire you … ?” Charles laughs and cuts me off. He’s already come back once; he’s confident he can do this. He’s past inspiration for 2016, looking even further ahead, even if he has mentioned multiple times that he’s looking at this one day at a time.

“It’s not even about that,” he says. “Guys are still getting paid at what, 32, 33?”

I mention Matt Forte, the Tulane running back drafted ahead of Charles in 2008, now 30, and who just signed for three years and $12 million with the Jets.

“Yeah,” Charles says, gripping his daughter’s hand. For the love of the game is a nice sentiment, and Charles’ decision to give it one more try isn’t strictly fiscally motivated. Still, he’s also repeatedly stated another purpose to me throughout the afternoon, and the reason he quit track after his sophomore season at Texas in order to focus on football: to provide for his family.

Carey Windler, an orthopedic surgeon who served as team doctor for Texas men’s athletics from 1986 until last year, says that 30 or 35 years ago, Charles wouldn’t even be thinking about his next contract. It’d already be over for him.

But orthopedic surgery has thankfully evolved since then. Years ago, a torn ACL was simply stitched back together; now, it’s replaced with a completely new ligament, either from elsewhere in the knee or from a cadaver, and the outpatient procedure can be completed in as little as 90 minutes. This time around Charles opted for two stem cell replacement treatments, something he didn’t do for his left knee. The rehab has changed too. No longer is the knee kept immobile for four to six weeks following surgery. Charles notes that even the rehab equipment at the Chiefs’ facilities varies greatly from what he used in 2011-12.

But the one barrier on the road back to greatness that is impossible to remove is kinesiophobia, or fear of movement. Windler says it affects all athletes returning from a major injury. The memories of the snapping ligament, the pain of recovery, and the long, arduous rehab stick with athletes when they return to the field, often hindering their ability to let loose.

“Jamaal was in great shape, and then out of the blue, something happens,” Windler says. “So they recover, but there’s this phobia of reinjury. It takes time for that to extinguish.”

Charles’ condo walls are mostly decorated with photos of his family and himself. But there’s also a signed portrait of Adrian Peterson, bearing the inscription: “Just think, we could have been in the same backfield at UT???” Peterson also tore his ACL plus his medial collateral ligament in 2011, and ended up winning the NFL MVP the following season. Peterson and Charles, who ran track against each other in high school, pushed kinesiophobia out of their minds once. Charles still has to prove he can do that again, with his first test looming in September, when the NFL regular season begins.

“There are some athletes who make us look really good, and some,” Windler says, “make us look even better.”

Two weeks before I met Charles, he found God. Again.

During Pro Bowl weekend in January, Whitney Charles heard of an event called the The Increase, held over four days in Colorado Springs, and convinced Jamaal to attend the Christian conference along with hundreds of other NFL athletes and their wives. After a long cycle of sermons, workshops, and worship, the final day was an opportunity for those who wanted to get baptized.

Charles was baptized as a child, but beyond mandatory church attendance, the whole “saved” thing didn’t mean much to him until recently. As a rookie with the Chiefs in 2008, he was enthralled by the debauched athlete’s life: namely money, jewelry, and women.

“I wanted to be called [by God] when I wanted to be called on,” Charles says.

Seated at the far end of where the baptismal was taking place, Charles wondered aloud if this was that time, even though everyone ready to take the plunge wore swimsuits while he and his wife were in the clothes they’d worn all day.

“The spirit was talking to me,” Charles says, his hand fluttering over his heart. The calling was loud and clear, and he was baptized for the second time on the spot. “I felt reborn again—I have a new body, a new mind, and a new spirit now.”

Over the last two weeks, the Playstation controllers have gathered dust and his turntables have remained unplugged. Charles opens a small brown box on his kitchen countertop, eager to see what’s under the flaps. He pulls out a stack of medium-sized religious texts, more substantial than Chick tracts but less bulky than a pile of Bibles.

“I used to play a lot of Madden online, Grand Theft Auto, get on the turntables, try to spin,” Charles says. “I stopped playing video games to read more about Jesus. I never read like that in my life.”

The first Chief to attend the conference, he has a couple teammates ready to sign up after this offseason. It’s the least Charles can do, he says, as he hopes to leave his mark off the field in the same way he has on Sunday afternoons. He wants to be an inspiration to anyone who feels lost, like he was.

“They can see a spiritual man in the locker room,” Charles says. “They don’t have to see what I saw when I came into the locker room.”

He also has come to grips with the notion that that Chiefs locker room won’t be his for long, even if he does come back strong in 2016. West and Ware were extended with identical two-year, $3.6 million contracts on Mar. 31. The cheaper, healthier, younger versions of Charles proving to be capable replacements for the veteran led to offseason speculation that the Chiefs might be better off without him at all. Even Hall of Fame running back Marshall Faulk said, in an interview with The Kansas City Star, “Why does Kansas City keep Jamaal Charles when you saw Spencer Ware and Charcandrick West? For what reason?”

Charles says he told Ware and West during the season that their goal is to take the starting Chiefs job from him, and that, if he was ever back on the field with them, he’d try to snatch it right back.

“It’s helping your brothers out, and they’re my brothers. But if your shoes are called for, you gotta take advantage of that time, man,” Charles says, “because you don’t know when that opportunity is going to come up again.”

And that’s been the theme of much of our interaction today: his legacy, and more specifically the unique position he’s in this offseason to decide how the world will remember Jamaal Charles. Sure, he’s concerned about how he’ll be viewed in the pantheon of great running backs. If he retired this offseason, his 5.5 yards per rush would rank No. 1 all-time for a running back since the NFL and AFL merged in 1966, better than Jim Brown, Barry Sanders, and even his old pal Peterson. Creeping into the conversation even more frequently is his desire to be remembered as an inspirational figure: to kids who are told they are too small or not smart enough, to nonbelievers, to future fathers.

“I want to break a generation of … ” Charles trails off. “I want my daughters to have a father they can look up to. I didn’t see that when I was raising up, and I always wanted that.”

Cradling Makenzie in his arms as he heads back upstairs for the night, Charles is focused on family. Tomorrow he will wake up and climb that steep mountain toward immortality again, and as painful and frustrating as it may be, he’ll do it again the next day too. He came back once before, and until proven otherwise, he says he will reach the top.

“Knowing him and his work ethic, he’ll come back just as strong,” Cosby says. “Someone out there is going to say he’s done. He’ll find that and use it. He’s different.”

Photos from top:

Photo by Ryan Nicholson

Charles is helped off the field after tearing his ACL during the third quarter on Sunday, Oct. 11, 2015, at Arrowhead Stadium in Kansas City, Missouri; Keith Myers/TNS via ZUMA Wire

Charles and his daughters Mackenzie (left) and Makaila (right) dance to “Hit the Quan” in the Gymboree below their condo; Ryan Nicholson

GIVING BACK

Texas legend Charles finds peace in mentorship

Jamaal Charles is a man at peace.

He left everything on the football field during an 11-year NFL career that saw him retire as one of the most explosive running backs ever to lace them up. Only two backs in the history of the league have retired averaging at least 5.2 yards per carry on a minimum of 750 attempts.

The iconic Jim Brown, who died two weeks ago, ranks second. The first? Charles at 5.4.

The Texas ex still carries the aches and pains in his joints after a distinguished career that will get him some Hall of Fame votes. He spends his days in Austin with his wife Whitney, his daughters Makaila and Makenzie and his son Isaiah while heading his Jamaal Charles Family Foundation and genuinely enjoying life.

When he was asked to be the featured speaker at Tuesday night’s Austin Area High School Sports Awards at the Long Center, Charles saw it as a great opportunity to share his story with more than 250 of the best athletes in our part of the state.

“Kids are beautiful,” Charles said. “I care about

RON CHENOY/USA TODAY FILE PHOTO

RALPH BARRERA/AMERICAN-STATESMAN FILE PHOTO

Cedric Golden

Columnist Austin American-Statesman USA TODAY NETWORK

them and I care about motivating them. Staying in school is important, Be respectful to your elders and your teachers. Be respectful to your coaches. It goes a long way. So that’s what I really care about more than anything.”

Charles grew up in the Golden Triangle in Port Arthur, where former NFL star Joe Washington, former Dallas Cowboys coach Jimmy Johnson and singing icon Janis Joplin put the town on the map.

Raised by his mother, aunt and grandmother, Charles was an elite athlete in Port Arthur but struggled with a learning disability and bullying from classmates.

He was placed in special education classes in elementary school, but despite his challenges in the classroom, blossomed on the football field and on the track. He starred in the Special Olympics, and by the time he reached Port Arthur High School, a path in college and possibly professional sports had been forged.

Charles dreamed of following in Washington’s footsteps, and after producing an incredible run that included a national championship at Texas in his freshman year, four Pro Bowls, and two All-Pro selections with the Kansas City Chiefs, he has thrived as a role model for others with similar dreams.

When he moved back to Austin full-time after retiring from the NFL in 2019, Charles, who had already been involved with the Special Olympics in Kansas City, hooked up with the Austin-area Boys & Girls Club. They have partnered to provide support and mentorship to club kids, offering opportunities to interact with Charles and other Texas legends, including Derrick Johnson, Michael Griffin, Quan Cosby, Michael Huff, and Brian Orakpo. The legends will be conducting a camp for members at the Ed Bluestein location on Friday.

“Jamaal and Whitney work so well with the Boys & Girls Club, and we come to numerous events,” said family friend Stevie Lee, a former Texas football player who now works in Austin real estate. “They understand there are kids out there who need mentorship and leadership just to get a head start in life.”

Charles could spend every day at home and on the golf course if he wanted to — he cashed more than $34 million in NFL paychecks during his career — but he’s finding time to give back. He and his wife, whom he met after a UT track meet in 2006, serve on the board of the Boys & Girls Club of the Austin Area and are using their platform to bring light to the lives of young people.

Jamaal Charles ran for 7,260 yards in 11 NFL seasons. The Texas legend is the keynote speaker at Tuesday’s all-star preps event at the Long Center.

Tuesday night is another opportunity. The area’s best and brightest young athletes will love hearing about his journey from humble beginnings to stardom.

“It means a lot because they don’t always get to see a lot of people (like me),” Charles said. “They find out it’s someone they’re able to touch and see that it’s just a normal person.”

After rushing for more than 4,100 yards and 50 touchdowns in his final two seasons at Port Arthur Memorial, including rushing performances of 400, 371, and 258 yards as a senior, the Parade All-American captured gold medals in both hurdles events at the UIL Class 5A state track meet in the spring of his senior year, after he had signed with Texas to play football.

He flashed his enormous potential as the Longhorns’ third-string back behind Selvin Young and Ramonce Taylor as a freshman, still finishing as Texas’s second-leading rusher behind quarterback Vince Young. Charles finished with 878 yards while averaging a team-best 7.2 yards per tote. He’s the program’s fifth-leading career rusher and retired as Kansas City’s all-time rushing leader with 7,260 yards, a number that would have approached 10,000 had his knees not given out.

These days, Charles enjoys the quiet life at home while striving to empower young people and be the male role model that he lacked in his young life. The same drive that pushed him to disprove the nine teams that took running backs ahead of him in the 2008 draft is laced with a quiet compassion that pushes him to bring light and energy to those less fortunate.

“I just try to stay humble and gravitate to kids and tell them to be humble,” Charles said. “I try to motivate them to be doctors and lawyers, not just be an athlete. I’m an athlete, and that’s fine, but these kids need to know they can do anything they want in life.”

He and Johnson will one day join former Texas priest and Chiefs’ Hall of Famer Holmes. Beyond that, Charles is considered a long shot to make it to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, even though his numbers are comparable to those of Terrell Davis, minus the two Super Bowl rings.

His stats may not add up to a gold jacket in Canton, but Charles is already a Hall of Fame role model.

Aaron Williams

In Aaron’s youth, a chance meeting with Longhorn weightlifting coach Jeff Madden put him on the path to becoming a Longhorn. At 12 years of age, he was invited to the Longhorn locker room to meet Roy Williams, Cedric Benson, Vince Young, and many others. He was hooked on Texas.

Three-year defensive back who appeared in 37 games, including 23 starts in his last 26 games, at cornerback and on special teams … declared for the NFL Draft as a junior … 2010 Nagurski Trophy and Thorpe Award watch lists … second-team All-Big 12 in 2010 … posted 106 tackles (64 solo), three sacks, 12 TFL, three pressures, four INTs, 24 PBU, six forced fumbles, one fumble recovery and five blocked punts …

Aaron says about defensive back coach Duane Akina. He was a quarterback at Washington , then built the Desert Swarm defense at Arizona before coming to Texas. He was the architect of the DBU (Defensive Back University). Aaron considered going to Auburn to be coached by Will Muschamp, but instead Mack Brown hired Muschamp to come to Texas. Muschamp pushed the players to their limits and made them winners.

Selvin Young

CEDRIC GRIFFIN

Cedric Griffin is physically tough and a competitor in pillow fights and wrestling. He is also not shy about showing off his talents with flashes of brilliant play. With his teammates, his moods vary from mellow, serious, quiet to goofy. But he thrives in the locker room, preparing for a game with a playful demeanor.