Joe Don Looney- UT beat O.U. on Saturday, stopping the star sooner back. There never was a player so aptly named as Joe Don Looney.

1963 Texas O.U. game by Roy Jones

TEXAS-OU MEMORIES: The hype leading up to the annual bloodletting at the State Fair in Dallas always harkens me back to the best game ever in the series.

Since that first game in 1900, the Longhorns and Sooners have faced off 118 times, but only once have the teams been ranked #1 and #2 in the nation.

Sportswriters dubbed it “The Game of the Century.”

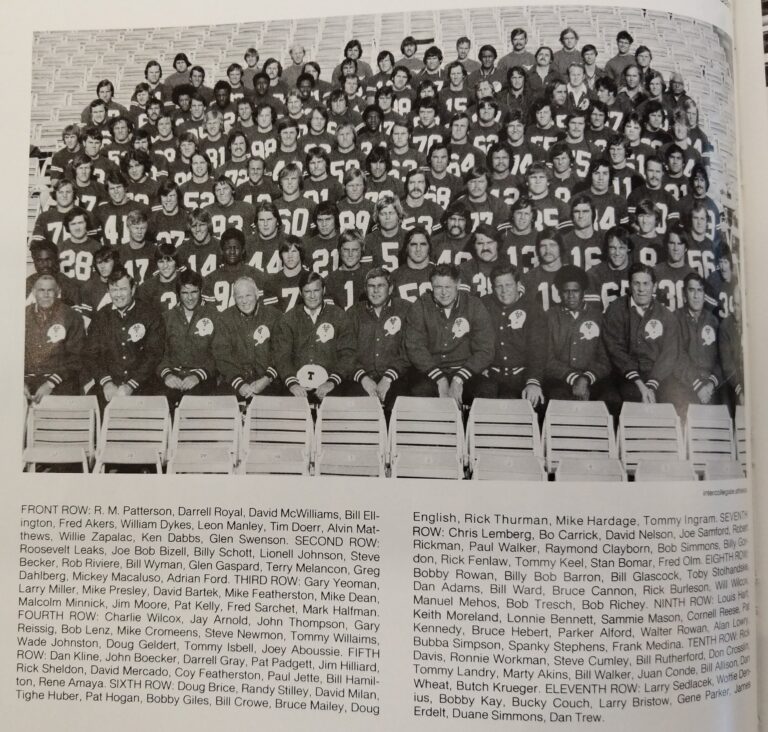

That was in 1963, and I had a front-row seat to history as the senior student manager of the soon-to-be national champion Longhorns.

I had been there as a manager for the three previous OU games, too, although I missed the first half of the 1962 game because I was in jail. We won’t talk about that.

The last time either Texas or Oklahoma was #1 going into what was then called the Red River Shootout was in 2008. OU was #1, but Texas won 45-35 and went on to play for the BCS National Championship.

The last time Texas went into the OU game ranked #1 was 40 years ago. That 1984 game didn’t settle the bragging rights that make the rivalry so intense. It ended in a 15-15 tie, and there was no overtime playoff back then.

In 1963, Oklahoma had upset USC the week before and was moved to #1 in the Top Ten polls. Texas was #2 after near-misses with a national title in 1961 and 1962.

Texas won the grudge match 28-7 and took over the #1 ranking en route to an 11-0 season and the school’s first national championship.

Much of the intensity in the rivalry is due to the fact that many of the Sooners are actually from Texas. Longhorn fans view them as turncoats, and Texas players are out to show them that they made a big mistake.

As senior manager I was in charge of putting the “bulletin board material” on the locker room wall to fire up our players before each game. That “material” comprised clippings from newspapers (remember them?) in which an opposing player or coach said something inflammatory about the Horns. Comments by sportswriters often served the same purpose.

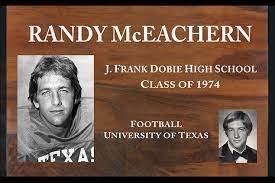

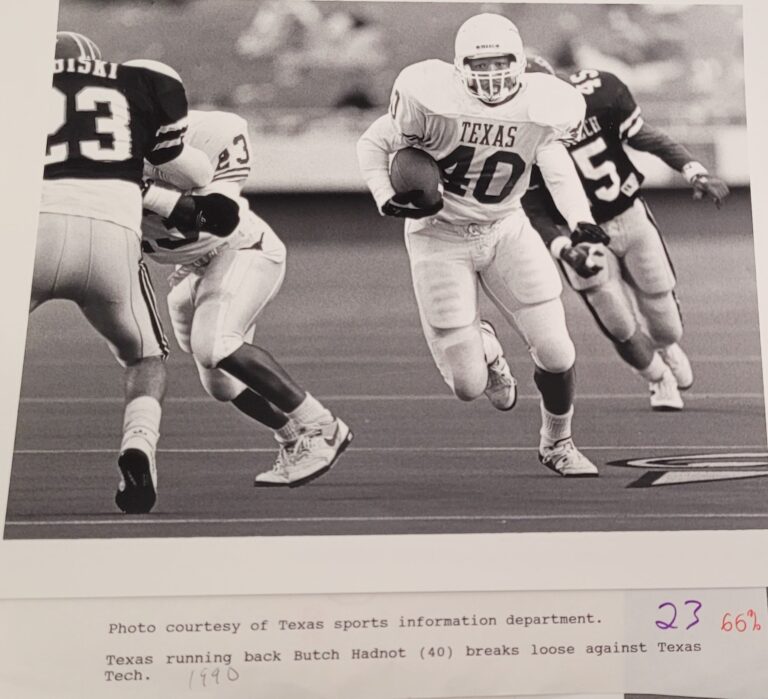

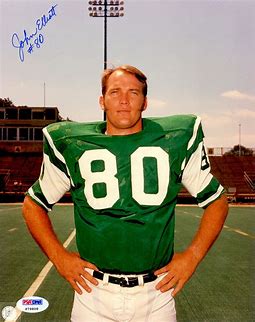

I had no trouble filling up the wall in 1963, thanks to a Fort Worth native turned Sooner. Star halfback Joe Don Looney, who had been a junior college All-American the year before, was the Cassius Clay of the gridiron.

His mouth was the only thing bigger than the sculpted muscles of a weightlifter. He had to have custom made uniform pants to fit his bulging thighs.

Looney had a good game when the Sooners rose to #1 by beating USC the week before the Texas game. In an interview with the Dallas Morning News, he disparaged the Longhorn offense and boasted that the Horns’ defense would be easier for him to run through than USC’s.

Them’s fightin’ words, podner!

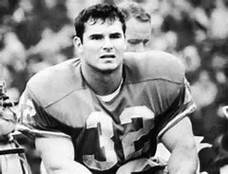

Two of the Longhorn defenders especially jacked up by Looney’s comments were senior tackle Scott Appleton, who Assistant Coach Mike Campbell said was only blocked one time the entire 1962 season, and a fiery sophomore linebacker with a 20-inch neck and a nose for the ball, Tommy Nobis.

I know it’s hard to imagine with so many linemen today weighing 350 or more, but Appleton and Nobis were the biggest players on the Longhorn team at 235 and 225, respectively. Two hundred of that was heart in each of them.

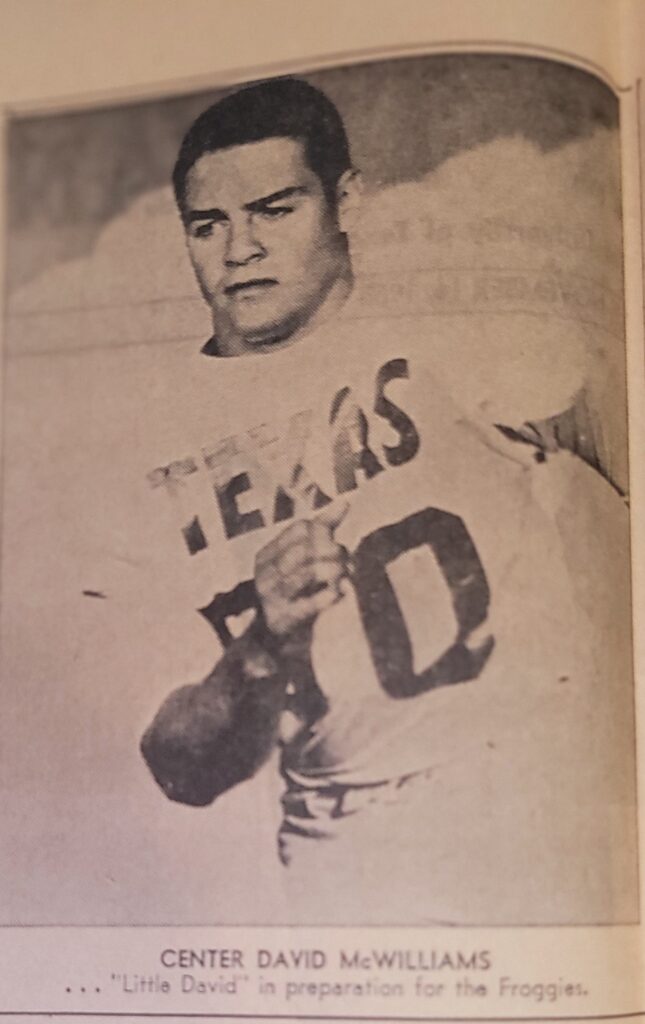

Texas tri-captain David McWilliams, only 188 pounds, had to line up against 6-6, 245-pound tackle Ralph Neely, who went on a spectacular 13-year and Ring of Honor career with the Dallas Cowboys.

McWilliams said Neely taunted him, “What are you doing out here, kid? You’re too little. You’re gonna get hurt.”

McWilliams acquitted himself well and went on to be the head coach at Texas Tech and later his alma mater. At 82, he still runs the Longhorn Lettermen’s T Association.

Texas Coach Darrell Royal, a former All-American back and punter at OU schemed to stop Looney by assigning Nobis to follow him everywhere but the huddle on every play. It worked like WD-40.

Legendary OU coach Bud Wilkinson quit calling Looney’s number after six carries resulted in an Appleton-Nobis sandwich near the line of scrimmage. Looney netted only four yards for the day.

Appleton wound up with 18 tackles, one more than Nobis, and was named the nation’s Lineman of the Week. He went on to win the Outland Trophy as the nation’s top lineman.

Nobis became the linebacker that the Longhorns have been measured by ever since. He was all-Southwest Conference three times, All-American twice, and the Outland Trophy winner his senior year. He had a 40-year career with the Atlanta Falcons as a player and later front office official. The tackles he amassed during his rookie year remain a Falcon season record nearly 60 years later.

Oh, that offense that Looney belittled?

The Longhorns received the opening kickoff and marched 68 yards to paydirt. Royal’s “three yards and a cloud of dust” offense was so dominant that they threw only three passes the entire game, completing all three and gaining 28 yards.

Exactly half of that came late in the fourth quarter on a 14-yard TD pass to George Sauer Jr. — who just happened to be my roommate in the athletic dorm back at Austin.

Whatever happened to Looney, Appleton, Neely, Nobis, and Sauer?

Sadly, they are all deceased. Sauer, Neely, and Nobis all died of traumatic brain injuries caused by years of blows to the head in football.

Looney made the most headlines. Wilkinson kicked him off the team for “disciplinary reasons” the Monday after the Texas game. Despite his bad boy habits, the New York Giants drafted him in the first round in 1964. He lasted only 25 days there before being traded to Baltimore. There, he got only 23 carries plus a year’s probation for assault. He had his best year as a pro with Detroit, racking up 114 carries for 356 yards and five touchdowns.

But, once, when the coach told him to carry in a play to the quarterback, Looney refused and famously told the coach, “If you want a messenger boy, call Western Union.” That got him traded to Washington, where his highlight was pass protecting and smashing the jaw of an onrushing lineman with his fist. The Redskins refused to renew his contract. His final season was with New Orleans, where he rushed three times for minus-3 yards and retired.

After football, his life spiraled out of control — criminal charges, psychedelic drug use, and an Eastern religion where he served as caretaker for the guru’s elephant. He was only 45 when his motorcycle left the highway at a high rate of speed and flipped several times near Terlingua. His body was found 50 yards from the cycle, his windpipe crushed.

Sports Illustrated wrote a lengthy article about him headlined “The Greatest Player Who Never Was.”

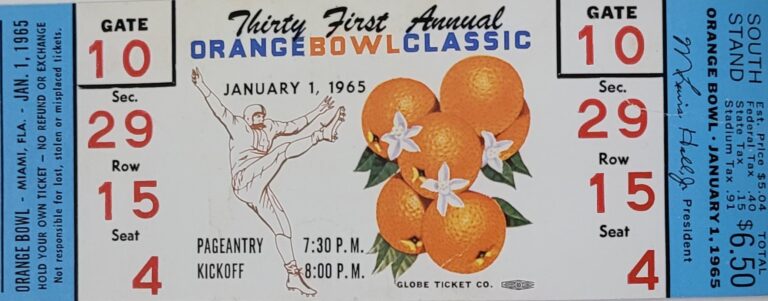

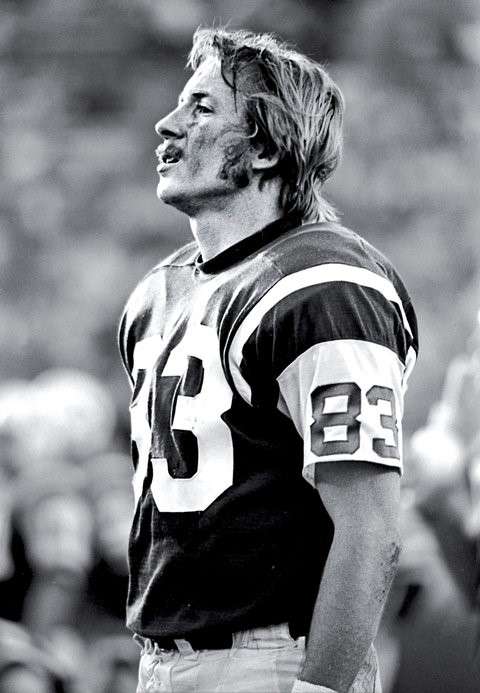

Sauer had a lot of the same individualistic qualities as Looney. After starring in the 1964 Orange Bowl upset of #1 Alabama as a redshirt junior, he shocked Royal by signing with the New York Jets to get in on the ground floor with their #1 draft pick, Joe Namath. Broadway Joe would later describe Sauer as “a gentle soul and the best receiver I ever had.”

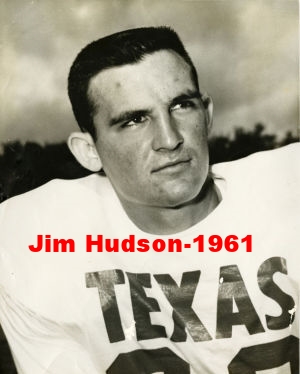

Sauer was part of what sportswriters dubbed the University of Texas at New York—the Jets team that upset the heavily favored Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III. Joining Sauer on the team were former Longhorns Jim Hudson, Pete Lammons, and John Elliott.

Sauer shocked the Jets by walking away from the game at the height of his career, calling football “inhumane.” One of his after-football jobs was sack boy in a grocery store. Co-workers didn’t know until after he died that he had been a pro football star.

Hudson also died of brain injuries linked to football and Elliott of cancer. Lammons, who had the distinction of playing under three legendary coaches, drowned in a freak fishing accident. Pete played for future Houston Oilers coach Bum Phillips in high school, Darrell Royal at Texas, and Weeb Eubank at New York.

Royal called Appleton “the best defensive lineman I’ve seen since I have been coaching.” As a three-year starter on both sides of the ball, he was the catalyst of the Horn’s defensive effort and rose to the rarefied air for a lineman by finishing fifth in the Heisman balloting. Appleton would sack the Heisman winner, Navy quarterback Roger Staubach, twice in the 1964 Cotton Bowl.

After Houston drafted him in the first round, the Oilers wanted him to put on more weight. Many a night, he took this skinny manager with him to Hill’s Steak House to help him eat all the steak the Oilers had ordered for him.

His pro career as a 260-pound tackle never approached his college feats. After three nondescript years with Houston and two with San Diego, Scott retired and became an alcoholic.

Old UT roommate and tri-captain David McWilliams said, “He drank a fifth of whiskey a day for a year or more.”

Scott ultimately turned his life over to Jesus Christ and quit drinking “cold turkey,” McWilliams said. But the damage to his body had already been done. While serving as a minister to the homeless in downtown San Antonio, he died of congestive heart failure at the age of 50.

He had declined to have a needed heart transplant. “He said he was right with God, and he died a short time later,” McWilliams said.

I was closer to Scott than most of the players because my freshman roommate was his Brady High School teammate, Bill Archer. They came to Texas on scholarship together, but Bill had a career-ending injury as a freshman. Scott visited us frequently, and we made a couple of trips to Brady together. Scott was a celebrity in Brady; one memorable trip home included riding with a highway patrolman friend for several hours.

Neely, who took top honors at the college and pro level, paid dearly for them, his widow said after he died in 2022 at the age of 78.

Janis Neely said he was in so much pain from brain trauma causing dementia, back and neck injuries, replaced knees, a hip, and shoulder, plus scoliosis of the spine that he told her he no longer wanted to live. But she said he added, “he would do it all over again.”

Neely was one of the ex-players who joined a lawsuit against the NFL to receive compensation as a result of suffering concussions and head trauma. When the case was settled in 2016, it was estimated that it would cost the league about $1 billion.