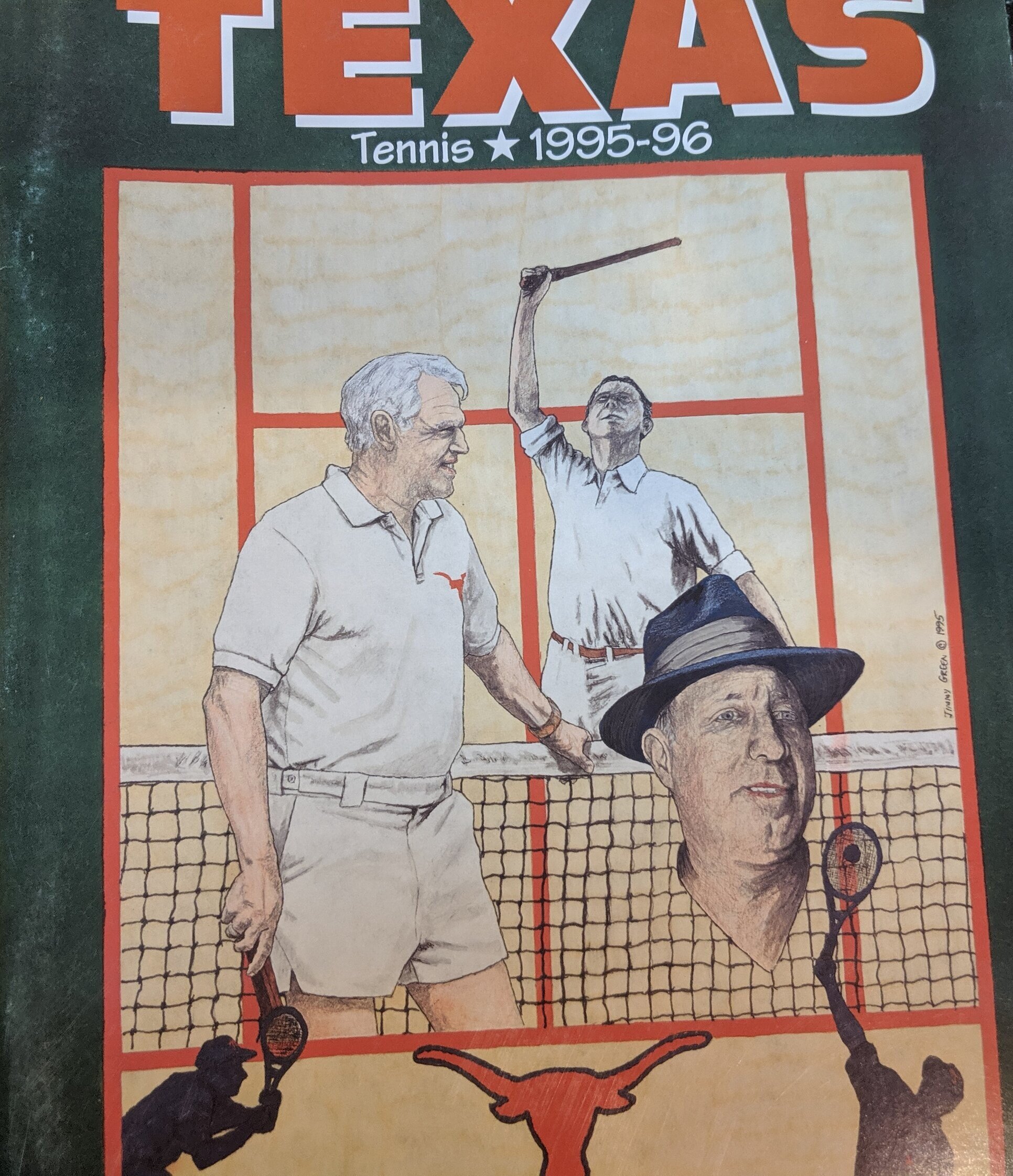

Jim Bayless – Game, Set, Match Coach Penick and Allison

The text and visuals of Jim’s years as a Longhorn tennis player are divided into two parts. Part I discusses the importance of Coach Penick and Coach Allison in building the Longhorn men’s tennis program. Part II’s link is listed at the end of this article and celebrates Coach Snyder’s influence on the Longhorn tennis program.

Part II also chronicles 1973, an interesting year in Longhorn men’s tennis history not known by many Horns. The Longhorns added a 12th man to the team- undefeated when asked to play – who was an influential political leader in later years.

Below is the Oral History of Jim Bayless.

In the Beginning

Jim Bayless recalls, “As youngsters learning to play tennis in my hometown of Houston in the early 1960s, my pals and I idolized the world’s top players who came to town to battle against one another at the River Oaks Invitational tennis tournament. To us, it was a veritable clay-court ‘Wimbledon’ in our backyard. We got to watch up close a remarkable generation of players such as the Aussies Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, Roy Emerson, and Fred Stolle, among other greats on the world stage. It kindled in me a keen interest in the legends who preceded them, among them Wilmer Allison, a native Texan whose name and fame I had known of even as a young boy.”

Game, Set, and Match by Jim Bayless

UT tennis adventures under Coaches Wilmer Allison and Dave Snyder, 1970-74

A Memoir by Jim Bayless

My four years as a member of UT’s varsity tennis team under Coaches Allison and Snyder gave me an education, in tennis as well as in life, which was unimaginable to me prior to my arrival on campus as a freshman in 1970. The guidance and example these men provided to my teammates and me in their ultimate mission to build character—to mold young men for good—were invaluable, for which I think of them, and thank them, every single day.

Yet the memories I revive here, offering the experiences and perspective of a single participant in just one four-year slice of a century-long Longhorn tennis program, represent only one pebble in an elaborate mosaic. For this reason, I encourage my fellow members of the herd to complement this account with reminiscences drawn from their respective eras at UT to round out the portrait. Through their recollections and mine offered here, may the reader as well as future teams come to know and appreciate the character, culture and camaraderie of the rich and colorful heritage of tennis at The University Of Texas.

Jim Bayless

PREFACE: ADVANTAGE . . . TENNIS!

At the outset, it must be understood that tennis is a sport different from the major sports that are virtually synonymous with college athletics in that tennis transcends a student-athlete’s college years, and in both directions age-wise. It is truly a sport for a lifetime—not only a sport to be played and enjoyed in one’s later years but in one’s early (sometimes very early) years as well. Point being, tennis players who compete at the intercollegiate level, many on athletic scholarships, routinely have been playing competitively on a national stage for several years by the time they suit up as freshmen. Most of my teammates had earned state and national rankings during their earlier years playing the junior tournament circuit. As a result, virtually every member of my four teams (as well as those on rival teams) had known, and likely often competed against, one another for years by the time they enrolled at UT. Consequently, our camaraderie was high, and our personal relationships were often years-long in the making well before we joined forces as Longhorn teammates. The dividends that this personal history pays are considerable and enduring.

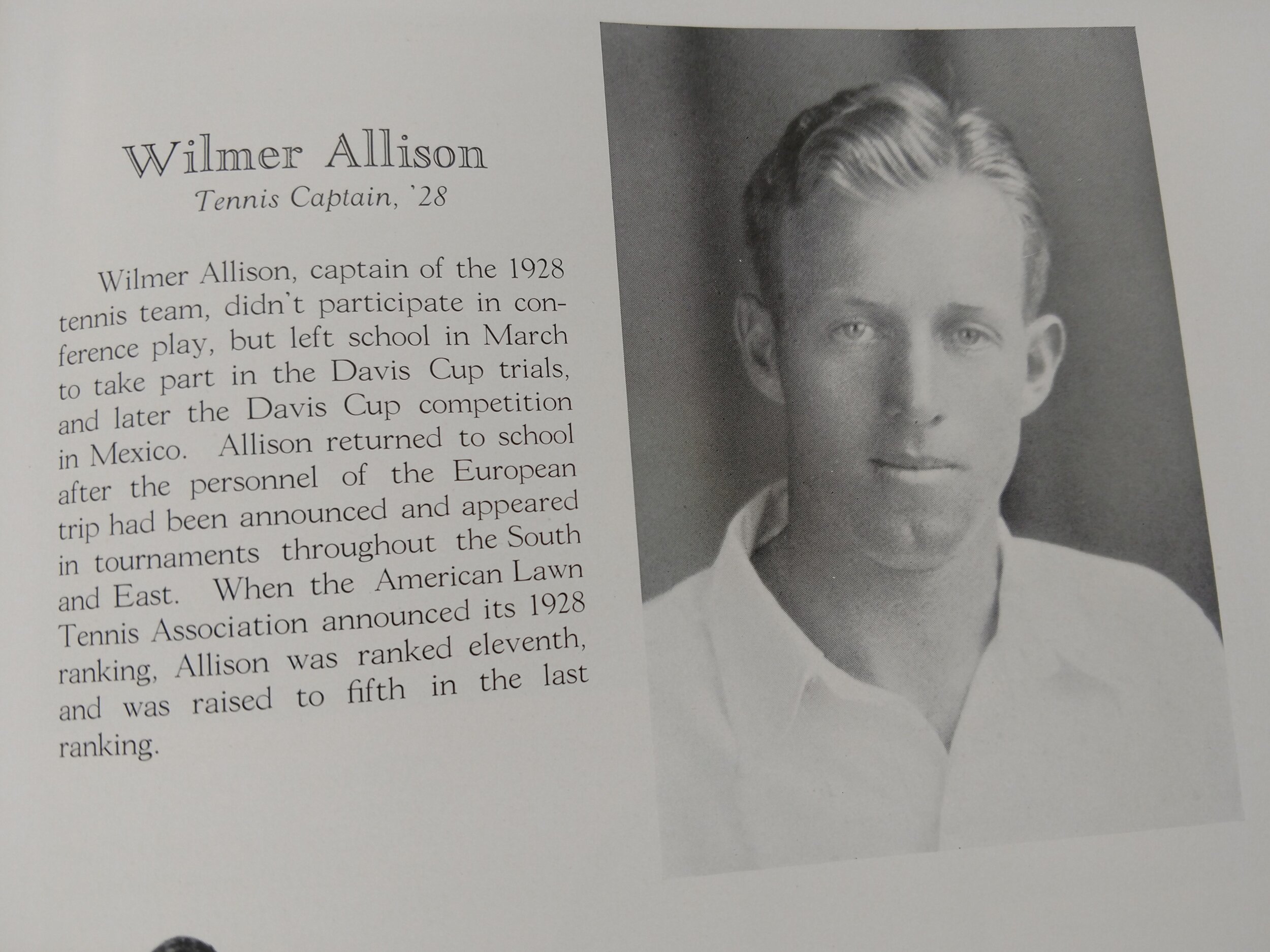

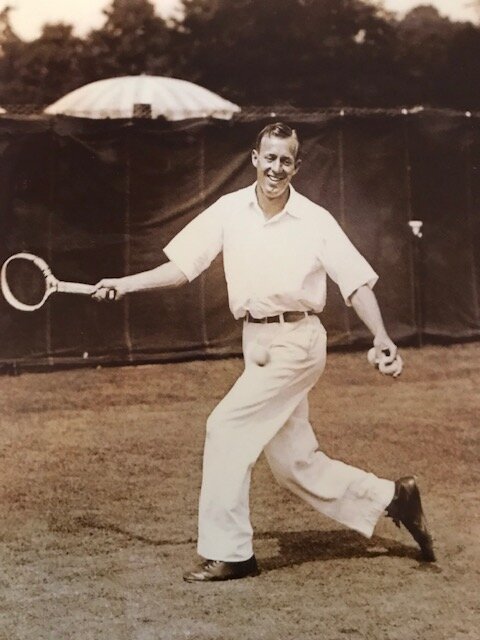

Wilmer L. Allison: Knight of the Tennis Round Table

As a youngster learning to play tennis in my hometown of Houston in the early 1960s, I idolized the world’s top players who came to town to do battle against one another at the River Oaks Invitational tennis tournament on the terre battue at the River Oaks Country Club. To my tennis pals and me this was a veritable clay-court “Wimbledon” in our own backyard. Getting to observe up close that generation of players (most notably the Aussies, Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, Roy Emerson and Fred Stolle, plus Rafael Osuna of Mexico and American Ham Richardson) kindled in me a keen interest in the legends who preceded them, among them Wilmer Allison, a native Texan whose name I had known for years before I had the pleasure of meeting him in person.

My interest in Wilmer Allison was piqued all the more when I learned that he, along with other greats of the 1940s and ’50s—Gardnar Mulloy, Billy Talbert, Jack Kramer, Ted Schroeder, Vic Seixas, Dick Savitt and others—were friends of my maternal grandfather, Ernie Langston, a co-founder of the River Oaks tournament in 1931. I remember a plaque on display at the entrance to center court that listed the names of past champions. I noted the name Wilmer Allison,

a five-time finalist who won the tournament only once, in its second year. We tennis tykes envisioned these players, both present and past, as a version of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, clad in all white. We were hooked on the history of the game as much as on the players’ athleticism, their chess-like strategizing, their . . . mystique. When I met Wilmer Allison, one of the “knights” of the golden era, then age 61, at a boys’ 14-and-under tournament at Caswell Tennis Center in Austin, and certain other elder statesmen who were past Longhorn lettermen, it began to sharpen my hazy notion of striving to play tennis at UT myself.

Page 1

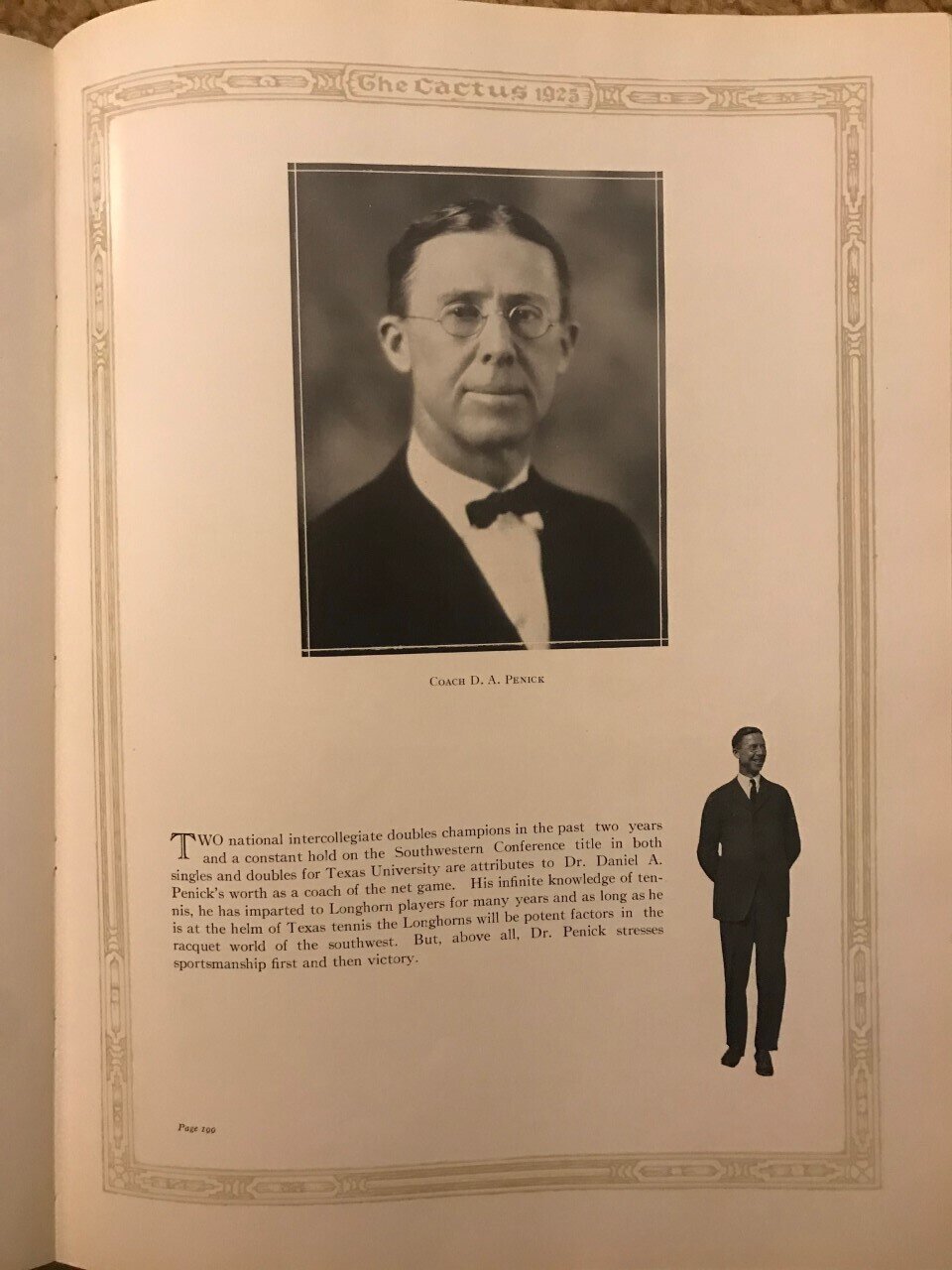

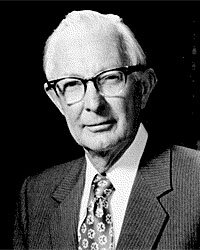

Daniel A. Penick, Ph.D.—“The Doctor”

To understand the history and culture of the University of Texas tennis program, one must first become acquainted with Daniel A. Penick, Ph.D. Though he passed away in 1964 at age 95, when I was just 12 years old, his influence continued to pervade the program, thereafter led by Coach Allison, his foremost player who, like virtually everyone else who played at UT under Dr. Penick, respected if not revered him.

“The Doctor,” as his players affectionately called him, was a bespectacled, quiet and scholarly man of distinction—firm and forthright in manner. He was a professor of Greek and Latin, a student of Sanskrit, a Phi Beta Kappa and an elder in the Presbyterian Church. He led the UT tennis program from its inception in 1899 (formally in 1908) until his retirement in 1956, an amazing 58-year run. As coach at the university, tennis director of the University Interscholastic League, president of the Southwest Conference and president of the Texas Tennis Association, Dr. Penick was the father of Texas tennis and a key contributor to the development of the sport throughout the state.

The Doctor appeared at daily practice always dressed in a coat and tie. He instilled in his teams a strong ethic of hard work, fair play and courteousness above all, never tolerating a cross word or histrionics by his players (who, by the way, had to wear shirts). Over the years, we heard time and again from Coach Allison, and subsequently from Coach Snyder, stories of Dr. Penick and the lessons he imparted. The Penick imprint remained crystal clear, as we would come to learn over the next four years of athletics and academics at the University of Texas.

Page 2

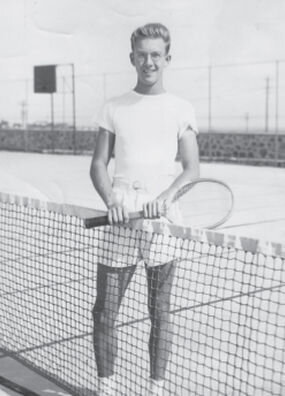

By Luck of Domicile, A Longhorn At Last

Longhorn lightning struck in February 1970, during my senior year at Lamar High School, when I received a letter from Coach Allison offering me an athletic scholarship, which I accepted by return letter immediately. I had much to be thankful for; for starters, the fact that I was born and lived where I did, for if you were not a Texan, Coach Allison was simply not interested. Like his mentor and coach Dr. Daniel A. Penick before him, Allison believed strongly that recruiting efforts at UT, a state-supported institution, should focus on home-grown talent only. Those from elsewhere need not apply. [1]

I was beyond thrilled about the upcoming chapter of my young life enrolled at UT with the honor and privilege of playing for the University of Texas at Penick Courts in Austin.

My transition as a freshman at UT that August was seamless, facilitated by long-standing friendships with virtually everybody on the team, kept fresh over the years with occasional weekend visits by upper-classman friends at my home in Houston, and reciprocally by me at their homes around the state. The camaraderie was made complete by the fact that my doubles partner in the juniors, Dan Nelson of Austin—we had been ranked No. 1 in Texas that year— would be joining me as a freshman Longhorn too.

[1] Though apply they certainly did. Illustrative of Wilmer’s adherence to his principle of not doling out scholarships to out-of-state players straight out of high school was his turning down John Pickens of Alabama, the No. 2-ranked junior in the country and runner-up to Cliff Richey in the national junior finals in 1963. Even Pickens’s impressive credentials were not enough to sway Wilmer to grant an exception to his rule. (During my years, however, Wilmer did allow one walk-on to join the team despite his status as a “foreigner”: That student was from Maryland.)

Page 3

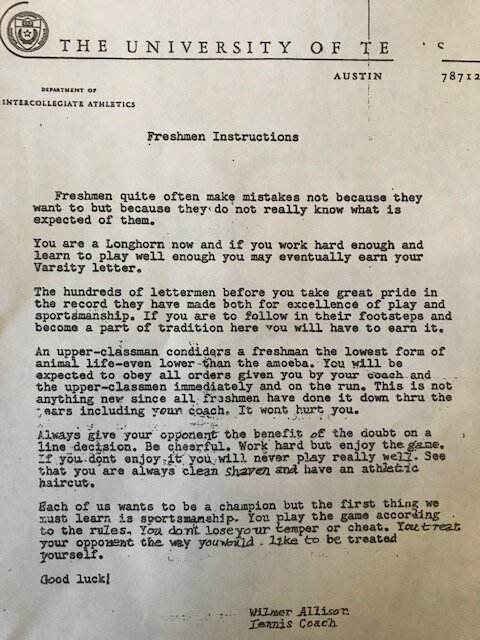

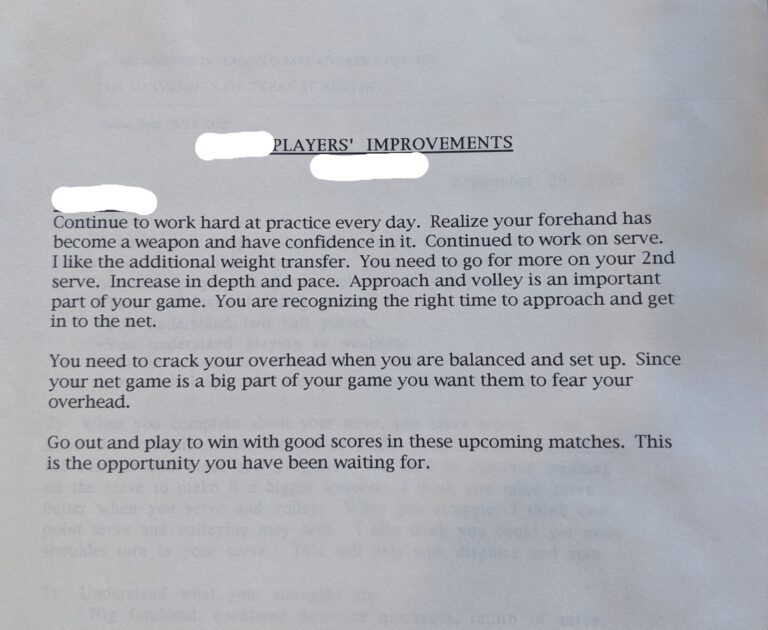

Coach Allison’s Rules of the Road: The “Freshman Instructions” Memo

Upon our arrival on campus, Dan and I received from Coach Allison additional guidance contained in his customary “Freshman Instructions,” which spelled out what he as well as upper-classmen expected of us rookies, whom he defined as “the lowest form of life, even lower than the amoeba.” Like his Texans-only policy in recruitment, Coach Allison stood firm on a number of other strict rules that we “amoebas” must observe at all times: punctuality, hard work in practice and match play, gentlemanly deportment, obedience, and good grooming. “See that you are always clean-shaven and have an athletic haircut,” the memo admonished.

In substance, though not style, Wilmer’s coaching methodology replicated that of his coach, mentor, and friend, Dr. Penick. Even as a coach who emphasized character-building above all, Coach Allison’s delightful wit shone through.

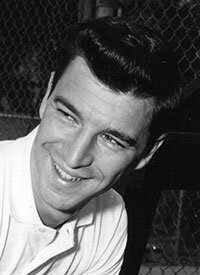

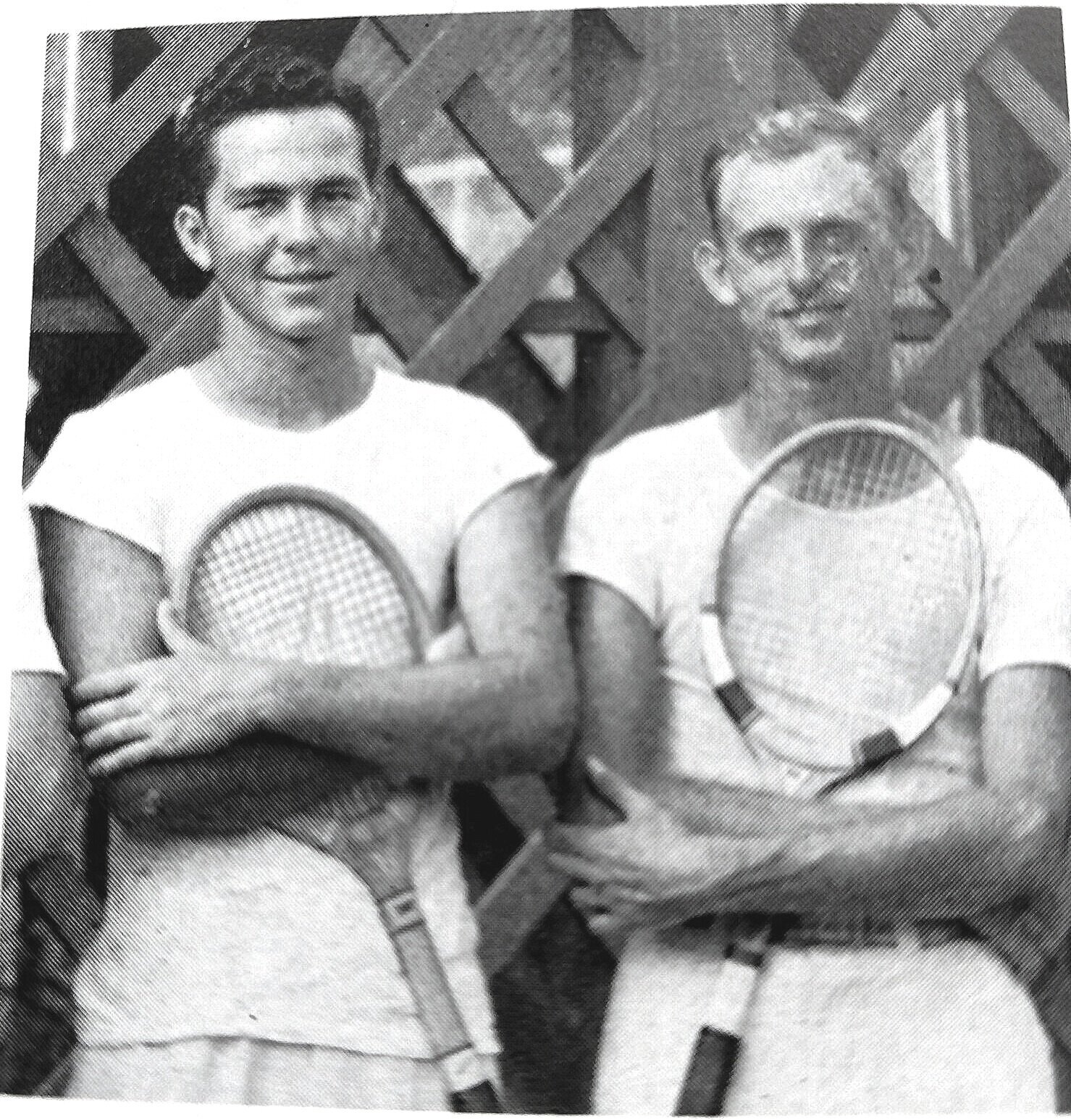

Wilmer Allison: Tennis Champion on the World Stage

My teammates and I were in awe of Coach Allison’s myriad tennis accomplishments and considered him the finest tennis player in UT history[2] After all, not everyone vaults from being ranked as the low man on the freshman Longhorn ladder to winning the national intercollegiate singles title the very next year, as he did in 1927. An extraordinary athlete who was offered a Texas League Beaumont baseball contract while a student at Fort Worth Central High School,

[3] Wilmer in 1930 became the first unseeded player in Wimbledon history to reach the final (beating the defending champion and top seed Henri Cochet of France in the quarters in straight sets),[4] earned two Wimbledon doubles crowns with partner Johnny Van Ryn in 1929 and 1930 and won the U.S. Nationals singles title in 1935 (defeating three-time Wimbledon champion Fred Perry of Great Britain in the semifinals).[5] In Davis Cup competition from 1928 through 1937, which in that era had a following akin to that of World Cup soccer today, he was a star worldwide, winning 32 of 44 Cup matches, the third most of any player in history behind John McEnroe and Vic Seixas. He and Van Ryn were the winningest U.S. Davis Cup doubles team with 14 victories, a record that stood for fifty years until broken in the mid-eighties by McEnroe and Peter Fleming. Allison’s U.S. teams made the Davis Cup championship match four times but, alas, never won the Cup. That he is enshrined in the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island, is no surprise.

[2] Longhorn superstar Kevin Curren of South Africa, whose extraordinary record in intercollegiate competition and on the ATP Tour in the ’70s and ’80s is detailed below, brought enormous prestige (not to mention other gifted South African players) to the University as well.

[3] Wilmer was born on December 4, 1904, in San Antonio, where his father, a psychiatrist, was superintendent of the San Antonio Sanitarium. The family later moved to Fort Worth, where his father became the superintendent of the Arlington Heights Sanitarium.

[4] Wilmer’s conqueror in that singles final, Bill Tilden, one of the greatest players of all time, magnanimously remarked post-match that “[Allison’s] no good and never will be.” Plainly, Big Bill spoke a bit too soon.

[5] We were dazzled by Wilmer’s stories about the tennis greats of the amateur era whom he had played—Tilden, Gottfried Van Cramm, Don Budge, “Les Quatre Mousquetaires” of France (René Lacoste, Henri Cochet, Jacques Brugnon and Jean Borotra), et al.—which he spun in a nonchalant, aw-shucks style, typically leavened with wit. One favorite: The supremely self-confident (and insufferably arrogant) Fred Perry, who had beaten Wilmer five times previously, once damned Wilmer with faint praise in a post-match press conference by acknowledging that, yes, Wilmer had played “all right, I guess—for a doubles player.” After Wilmer beat Perry at the U.S. Nationals at Forest Hills in 1935, Wilmer was asked by a reporter how he thought he had played in his upset win. He replied, “Well, I guess I played all right—for a doubles player.”

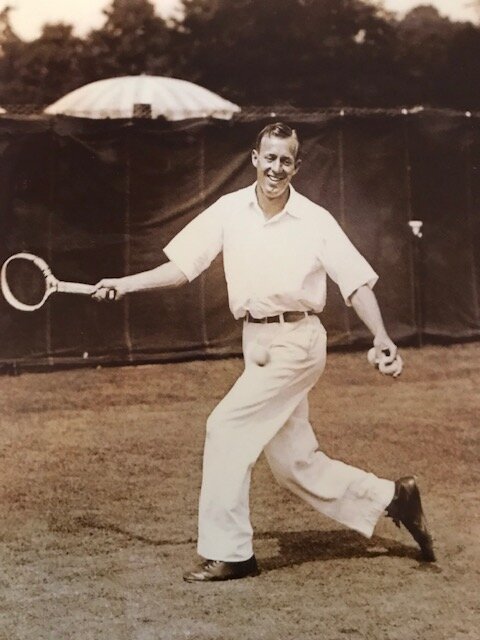

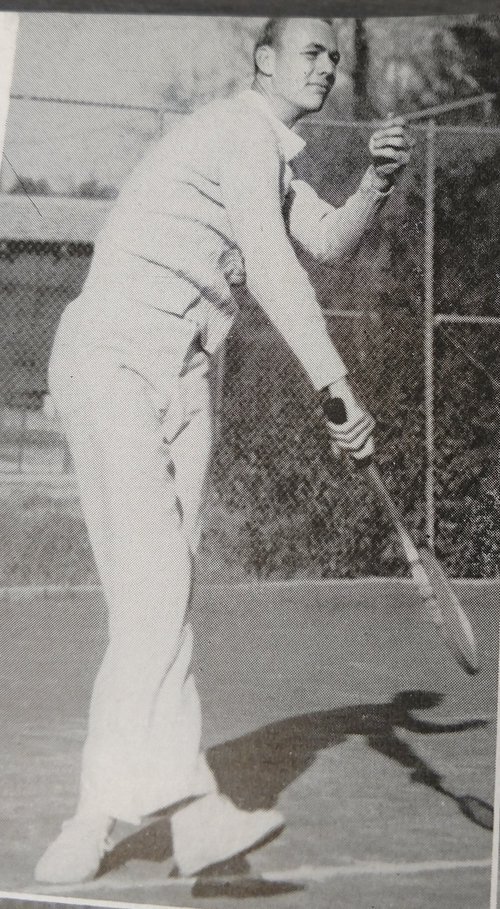

Coach Allison through the years

As a player and technician of the game,[6] Wilmer was known for his attacking, aggressive style bolstered by a big serve and a mindset to end points quickly. Among his shots most feared by opponents were his overhead smash (“Easiest shot in the game. You should never miss an overhead,” he told us) and his forehand volley (Jack Kramer in his 1979 autobiography declared it “the best forehand volley I ever saw as a kid, and I’ve never seen anyone since hit one better; Budge Patty came closest, then Newcombe”). His doubles excellence, from the left court, was unsurpassed (“It’s simple—just never let the ball hit the ground,” he explained). His coolness under pressure was self-evident: In a Davis Cup match against the ambidextrous Giorgio de Stefani of Italy in 1930 on the red clay of Roland Garros in Paris, Wilmer recovered from being down two sets to love, down two match points at 2-5 in the fourth set, down 16 match points at 1-5 in the fifth set—18 match points in all—to win the match, an astounding comeback record that holds to this day.

[6] Wilmer wrote three analytical white papers for a tennis book of instruction: “The Technique of Good Volleying,” “An Analysis of Expert Doubles Play,” and “On the Making of Ground-Strokes.” He appended this note to each 20 years later: “This article was written in 1935, but I would make no changes in what is written.”

Page 5

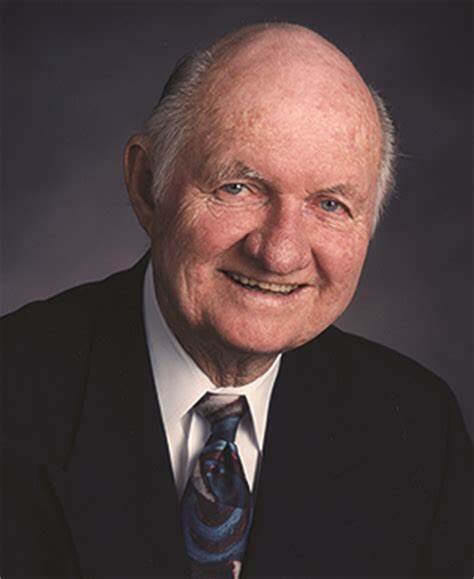

Wilmer Allison as Coach and Personality

Memories of Wilmer as a coach, friend and personality abound. In coaching, he was a minimalist, watching our practices from the stands at Penick Courts and rendering advice privately if at all.[7]

I believe that Coach Allison saw his overarching mission as coach to be building character and molding young men for good. Tennis was simply the vehicle by which he sought to accomplish that. After all, you can’t expect to control the ball until you learn to control yourself, hence the non-negotiable imperatives of personal discipline, competitive desire, fair play, mental fortitude and social maturity, which his coach and mentor, Dr. Penick, had inculcated in him when he was our age.

A video of the Tennis styles and techniques in the 1930’s is below.

Regarding academics, he made it clear that he expected us to make good grades, the reason we were in college in the first place. Fortunately, we all were pretty good students, even scholarly in some cases (witness three pre-med teammates in my freshman year, plus future lawyers, engineers and business school students among our ranks). The personal discipline forged over years of endless hours on the tennis court in practice and match play had some salutary carryover effect on our academic performance in most cases. We all understood the correlation between input and outcomes.

In dual matches against top schools, he would instill in us confidence and doggedness—and in the case of one sworn rival, a certain ruthlessness to boot, with instructions for us to “Send those Aggies home, crying like babies!”

Away from the courts or after hours, Wilmer was personable and good-humored. His passions were (a) golf (he sometimes would mysteriously disappear in the late afternoon when the putting green or driving range beckoned; ever the scratch golfer, he could still shoot his age without a care); (b) operating his amateur (ham) radio at home and in his car (a gold Buick Skylark, with license plate “W5VV – Radio Operator”); and (c) the renowned New Orleanian clarinetist Pete Fountain[8] Occasionally he would phone us in the evening in our dorm rooms, full of good cheer if not also a cocktail or two, which my funny teammate and roommate John Nelson called Coach’s “torpedo juice.”

[7] With one exception that none of us will ever forget: One day a teammate was having trouble with overheads. Coach Allison, attired as usual in slacks, Ban-Lon polo shirt (likely burnt-orange), dress shoes and his ever-present straw fedora, came onto the court, grabbed the player’s racquet and asked someone to hit him a lob. Never having seen him wield a racquet or hit a ball in our lives, we were dumbfounded. As the lob crested, Wilmer, then 67 years old and still in his street shoes, leapt as smoothly as Baryshnikov might and cracked an overhead with authority into the corner of the court. Handing the racquet back to the player and putting his hat back on, Wilmer, expressionless, simply said, “See, nothing to it” and returned to the stands.

[8] As a freshman, I drew the black bean to ride shotgun with Coach Allison on the 302-mile (five-hour) drive to Edinburg, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley for a match against Pan American University, a tennis powerhouse comprised mainly of Davis Cuppers from various South American countries. It soon became clear why I was awarded this assignment: Wilmer listened the entire way to Pete Fountain’s music on his 8-track tape player, gyrating to the Dixieland jazz beat while dreamily humming along, declaring, “That Pete, he sends me!” On a subsequent trip to New Orleans to play against Tulane (facilitated by the use of a DC-3, arranged somehow by Wilmer’s next-door neighbor, Dr. Walter Sjoberg, a dear friend and benefactor to us all), Wilmer took us with him to listen to Fountain perform at Pete’s Place in his native habitat, the French Quarter, on Bourbon Street. When Fountain saw Wilmer arrive, he called for silence as he introduced his friend to the audience with great fanfare as “one of the greatest tennis players that ever lived!” Wilmer was in rapture. David Nelson, the elder brother of two of my teammates and who had played for UT some years earlier, told me that Wilmer was so enamored of Fountain’s tunes (as well as those of trumpeter Al Hirt, also of Bourbon Street) that he once bought a clarinet for himself and took lessons. He soon recognized that he was so God-awful at it that he despairingly threw the expensive instrument in the trash.

Page 6

Wilmer also was a great teller of stories about his tennis forays around the world and his widespread personal friendships with the likes of actor Douglas Fairbanks and golf legend Bobby Jones[9] and other celebrities of the age. Or of his days as a colonel in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II as a pilot and commander of two different Air Force communication wings, once buzzing through the spray of the cavernous Victoria Falls on Africa’s Zambezi River, one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World.

He would entertain us with campfire tales of his travels to these remote lands, where “The natives were so huge that they had hands like hams and fingers like bananas!” and that “The mosquitos were so large you could track ‘em on radar!” And when he once landed in Greenland, he regaled us by declaring, “The wind was blowing so hard that it blew a manhole cover against the wall—and it stayed there for a week!”

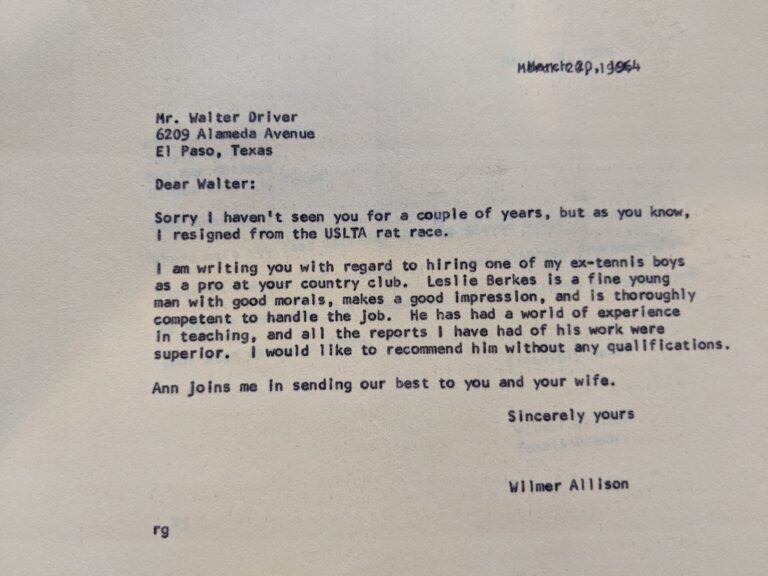

He also was a frequent letter writer, sometimes in longhand or otherwise typed with a font instantly recognizable as his, and usually in a jaunty style, with his typical closing of “Cheerio and pip pip!” He encouraged us to keep him posted on our travels while playing summer tournaments, which I faithfully did.

One time, however, Wilmer outdid his custom of using only a few words to get the message across by using no words as an even better alternative, as my teammate Marc Wiegand experienced to his chagrin. Having recently returned home to Austin after playing summer tournaments around the state, Marc paid a visit on Coach Allison to check in. Marc had grown a thin, David Niven-esque, reddish-blond mustache that was so pale and slight that it was discernible only in the right light and at the right angle; otherwise, it would have gone unnoticed. He and Wilmer caught up with each other over a pleasant conversation, and Marc then departed. Two days later, Marc received in the mail an envelope scrawled in Wilmer’s hand and bearing his return-address label. He opened the envelope only to find a single piece of paper with no writing on it whatsoever. But the paper did contain an item fraught with meaning: a single Gillette razor blade!

[9] A cute story that links two Longhorn heroes of different sports who were two generations apart: Bobby Jones gifted to his friend Wilmer the putter with which he had won golf’s exalted Grand Slam in 1930. Decades later, Wilmer, perhaps sensing greatness already in the future, in turn bequeathed Jones’s putter to Ben Crenshaw, then a young boy in Austin, who coveted the treasure as the equivalent of the Sword in the Stone. Ben’s father sent the club off to be cut down to size to make its length proportionate to his peewee son. Ben, of course, went on to become two-time champion of the Masters Tournament (1984 and 1995) and earn 17 other PGA Tour victories, not to mention three NCAA individual championships as an amateur and a Longhorn (1971-73).

Page 7

Practice, Practice, Practice

Under Coach Allison, our afternoon practices started at 2:00 p.m. precisely, Monday through Friday, at Penick Courts, located at the time about twenty yards south of the football field in Memorial Stadium.[10] As freshmen, we showed up early to fulfill our custodial duties—opening the padlocks on the gates and the dark shed that housed grocery carts full of balls (while dodging the Daddy-Longlegs in residence), placing the net sticks in the right spots on the courts and filling up and putting the hefty water jugs atop the umpire chairs beside each of the five Laykold courts.

Once done with our chores, we joined our teammates in drills before playing two-out-of-three-set matches that Wilmer assigned on a random basis, followed by doubles matches along the same lines. Coach Allison, who would be watching from the stands above, believed that the best training for matches was playing sets, and lots of them; the by-product was that the collective match results established the line-up with utter transparency and without argument.

[10] Having long been addicted to a daily diet of tennis year-round in the absence of rain or cold—Wilmer forbade us to play if the temperature was below 50 degrees, which in Austin deprived us all of six days in two years—we almost always played on Saturday and often on Sunday in addition, though Wilmer discouraged the latter.

Page 8

Sometimes elder lettermen such as Ted Gorski, a third-year law student at UT who had won the Southwest Conference singles title in 1966,[11] and his teammates Bill (“W.D.”) Driscoll and Larry Eichenbaum would be a part of the mix, as would John Mozola, a former No. 1 player who was then at UT Law School.[12] We would wrap up practice by hitting baskets of serves and then running the stadium steps and doing wind sprints on the track at Memorial Stadium—in our Wilson Skid-Grip tennis shoes, since proper running shoes were a luxury afforded only to the track team. We would lock up and return to Jester Dorm by 5:30 or 6:00 p.m. for showers and dinner and then hit the books at either the Academic Center or Main Library until 11:30 p.m. or later.[13]

On a football home-game Saturday each fall, Wilmer would arrange the annual Old-Timers Match, a social event in which former lettermen of all ages (some fairly carbon-dated) paired up with members of the current team to play doubles. It was another tool in Wilmer’s bag to enable us to meet and befriend previous generations of the UT tennis fraternity in the hope that long-running friendships would emerge. Did they ever—many lasting to this day some fifty years later.

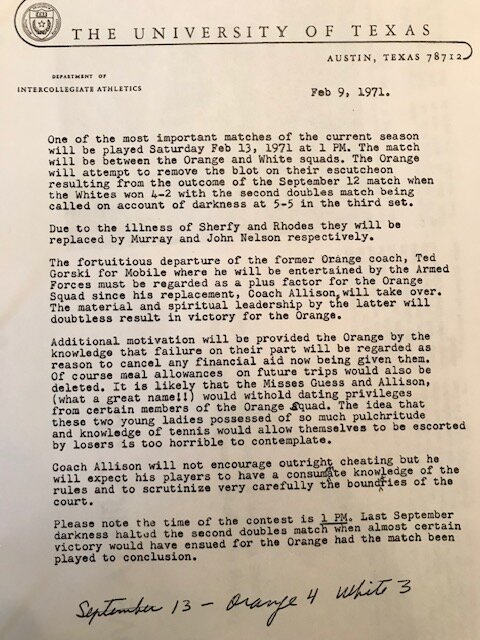

Of a more serious nature, one of the most important matches, the annual Orange-White grudge match, was scheduled in early February as a prelude to the season. This was announced by one of Coach Allison’s wry memos, written in elevated prose, which raised the stakes for each side of this intramural contest with playful “threats” of canceling financial assistance and meal allowances for those on the losing side and raking various players over the coals. Vintage Wilmer!

[11] Ted, who did not own a car at the time, was then serving in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserves. I was frequently on call to drive him to the feeder road on I-35 to hitchhike to his hometown of Fort Worth and back for his periodic meetings with “the Coasties.” He carried with him a huge poster with “Fort Worth” written in Marks-A-Lot on one side and “Austin” on the other. He said he rarely had to wait very long for a free ride door to door.

[12] Mozo was a master tactician of the game. I can still hear him shout, “When you lob, LOB! Two telephone poles high!”

[13] Admittedly, outbreaks of horseplay, which involved shaving cream, firecrackers or an offending teammate’s clothes and other belongings being removed and relocated elsewhere, were known to happen when circumstances demanded. Acts of retaliation were almost always forthcoming. Another disciplinary action was once taken by us vigilantes against an uppity freshman teammate (who shall remain nameless), who was kidnapped from his dorm room on a wintry Sunday morning. He soon found himself momentarily airborne as he let loose a desperate scream before plunging into the icy depths of Town Lake below. The medicine took, but only for a while.

Page 9

Freshman Season, 1971

In my freshman year our team had good depth, with any player capable of picking off anyone else on occasion. But the top of the lineup was clear: junior Avery Rush of Amarillo at No. 1 singles, followed by junior John Nelson of Austin, sophomore Ron Touchon of Amarillo (who had beaten me soundly in the state interscholastic singles final two years prior), Dan Nelson of Austin, and either Marc Wiegand of Austin or me, who were interchangeable at Nos. 5 and 6 singles. Starting with the traditional kickoff team tournament in chronically windy Corpus Christi, we then played the usual series of dual matches with a flurry of non-conference schools across the state and beyond. Our opponents included some smaller schools that seemed to be de facto Davis Cup teams of foreign lands, as well as domestic powerhouses like the nearly invincible Trinity University in San Antonio.

These were followed by the Southwest Conference matches at home and away, in round-robin format, which outcomes determined the final standings. This being Dan Nelson’s and my debut in intercollegiate competition, we were ready for action in the big leagues notwithstanding the usual butterflies that come with the territory, for which in tennis no preventive medicine has yet been found.

As it happened, we did respectably well. We finished third in the SWC behind national dynamos Rice University, led by superstars Zan Guerry, Mike Estep and Harold Solomon (who beat me in the quarters of the SWC individual singles tournament, held at Texas A&M that year), and SMU, spearheaded by two tough Aussies.

Page 10

With a knack for poor timing, I began to catch fire only after conference had ended, at the NCAA tournament, staged at Notre Dame that year. Though ostensibly I was cannon fodder in the first round against No. 18 seed Sashi Menon of the University of Southern California, the national junior champion of India of the year before, I came within just a few points of notching an upset, only to fall in three sets. That fed me into the singles consolation draw in hopes of partial redemption. Fortunately, I ran the table through the 32-man field, ultimately winning the unspoken title of “Best of the Worst.”[14] My opponent in the final was ambidextrous Bobby Bell of California State at Long Beach, whose forehands and wide-angled serves off of both wings took some getting used to, needless to say. Lucky for me, the match wasn’t a reprise of Wilmer Allison’s Davis Cup marathon against dual-handed Giorgio di Stefani in 1930, in which Wilmer overcame 18 match points to win; otherwise, I may have missed my plane.

As pleasing as my first year was at UT, on the court and in the classroom, the summer tennis tournaments thereafter provided the usual, extended satisfaction as well as further proof that for tennis, the year-round “season” never truly ends. After the NCAAs, three teammates and I took another long road trip to play the Pacific Northwest circuit through Oregon, Washington and British Columbia (including on the grass courts of the Vancouver Lawn Tennis and Badminton Club). These whistle stops lent us additional tournament experience and expanded friendships with a new batch of competitors from the West Coast and elsewhere, including some professionals who, unlike us collegians, were vying for the prize money on hand.

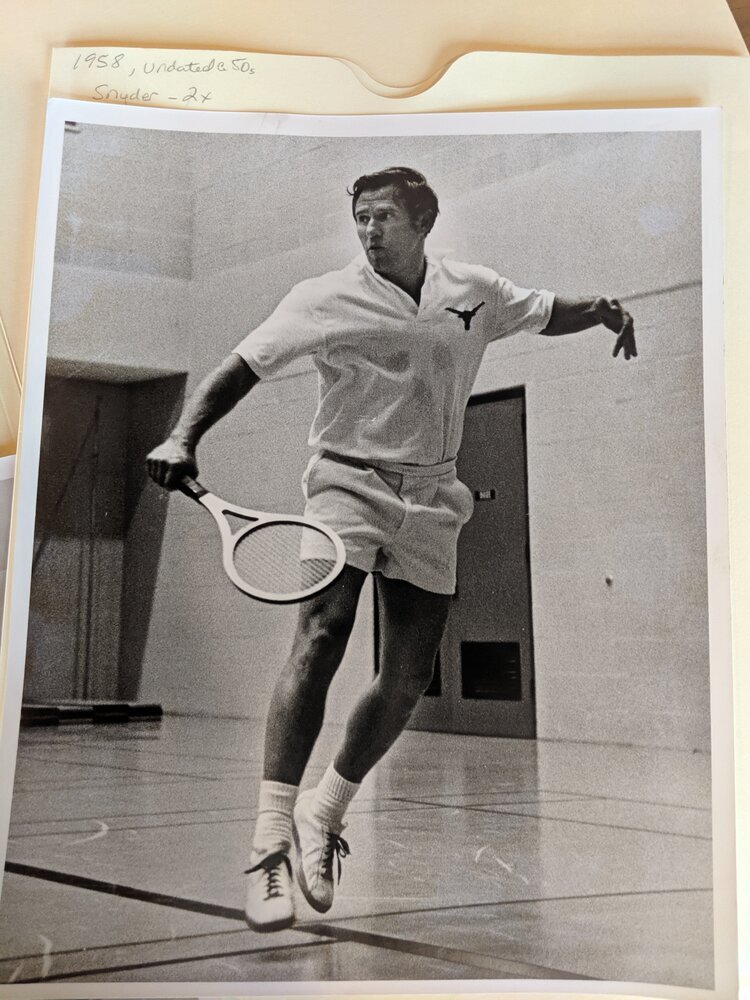

[14]I took heart in the fact that the only other NCAA singles trophy that year went to the actual champion, freshman Jimmy Connors of UCLA, who defeated Roscoe Tanner of Stanford to become the first freshman to win the title. To my inner Walter Mitty, this suggested that Jimmy and I have a lot in common (well, the first name at least). But the more gratifying encomium for me (and for Coach Allison) was being named an Honorable Mention All-American. Speaking of commonality, I learned four decades later that as a Longhorn, our future coach, the preternaturally self-effacing Dave Snyder, was likewise “consoled” by winning the NCAA consolation singles title as a sophomore in 1954.

Page 11

1972

Having lost only one senior to graduation the previous May, our team remained largely intact for my sophomore year, fortified by a transfer, Tommy Roberts of Fort Worth, a great friend since we were 14 and my incoming roommate. Unfortunately, the same was true for our main competition both within and outside the Southwest Conference. Predictably, our results mirrored almost perfectly the previous year’s, where we again finished third in the SWC with a 29-13 record, maintaining our edge over most of our Conference opponents, while striving for respectable performances against always-daunting Rice (35-7) and SMU (31-11). In addition, we got smoked by a new opponent at home that year, highly ranked University of Arizona, whose coach had played at Texas two decades before. Unbeknownst to us at the time, we would be seeing a lot more of him in the near future.

Jim Bayless Continued

Following the regular season, Dan Nelson and I represented UT in the Blue-Gray tournament in Montgomery, Alabama, as a tough prelude to the NCAAs at the University of Georgia in Athens. This was during the (short-lived) era of the nine-point tiebreaker, intended to prevent endless matches but which was inherently unfair because one player got five serves and the other four in the tiebreaker. Nonetheless, the device came in handy for me, as I won my first-round match over Brazilian Davis Cupper Carlos Goffi of the University of Corpus Christi on the ninth point in the third set—match point for each of us—in a three-hour struggle. Alas, my success was short-lived by losing in a tight match to Patrick Dupré of Stanford University, a four-time All-American. Since I’m a fan of the artifice of “indirects,” whereby one may imagine superiority over much better players by comparing wins or comparative scores, my loss looked better in retrospect when, years later, Dupré reached the semifinals of Wimbledon and was ranked No. 14 in the world.

Page 12

At the NCAAs, Dan and I each reached the third round of singles, where I lost to Paul Gerken, one of the four ferocious Trinity Tigers, which team dominated the tournament to win both the individual and team championships (Dick Stockton defeating Brian Gottfried, both of Trinity, in the singles final). By the “logic” of indirects, I was buoyed that Gerken beat the second seed, Eddie Dibbs of the University of Miami, by the same (lopsided) score two rounds later.

On June 20, a week after the NCAAs, Coach Allison announced his retirement as the Longhorns’ tennis coach after 15 years at the helm (for which he never took compensation, by the way). The news was not unexpected—Coach had pledged to stay until Avery Rush, John Nelson and Marc Wiegand graduated—and understandable given his distinguished lifetime of accomplishments, both as a coach and a player of international renown. He was entitled to declare victory and put his feet up at last. To convey our gratitude for what he had taught us, both on the court and off, and the great respect we had for him as a coach and mentor, we gave him a handsome gun case to indulge another of his favorite pastimes that involves placement, power and trophies of a different sort.

While we awaited word on who Wilmer’s successor would be, three of my teammates and I represented UT on the Pacific Northwest circuit again. We started in Eugene, Oregon,[15] with successive tournaments in Portland, Tacoma, and Seattle (all on hard courts), and Vancouver (on grass) and Victoria B.C. (on hard). In the Washington State Tennis Championships in Seattle, I had an early upset win over Jody Rush, who had been ranked No. 3 in Southern California the previous year, behind U.S. Davis Cuppers Stan Smith and Bob Lutz, before losing in the quarterfinals. Showing that early tennis friendships count for a lot, especially among fellow Texans, my doubles partner in the tournament was Howard Butt, a Trinity Tiger of the newly crowned national championship team.

Male-bonding among us Longhorn teammates was a natural for us 24/7, and year-round at that. In undertaking our tournament-laden summers, we would pile into someone’s car together and take off cross-country—the Deep South, the Northeast, or Pacific Northwest—or even Canada. Ed Innerarity volunteered his Plymouth Duster (Texas license plate: “6LOVE”[16] for the task this time around.[17]

[15] By chance, that tournament coincided with the U.S. Olympic Trials at the University of Oregon, where between matches we witnessed the track & field events such as the hurdles, whose contestants included a fellow Longhorn, Gordon Hodges. The Trials also featured record miler and Olympic silver medalist Jim Ryun of Kansas and Steve Prefontaine, Oregon’s revered long-distance runner. Notably, these two runners and their American teammates went on to compete in the Summer Olympics a few weeks later in Munich, Germany, the scene of the Palestinian terrorist group Black September’s hostage-taking and murder of 11 Israeli athletes.

[16] The News Tribune of Tacoma, Washington, was so impressed that it ran a photo of Ed holding his racquet aside the license plate in its sports section to publicize the tournament.

[17] The players in these tournaments, of all stripes and nationalities, were vagabonds, which was the nature of the beast. For example, at the Western Canadian Championships in Vancouver, B.C., one year, Felix Ponte, who played for Brigham Young University, once asked my teammate Bill Fisher, “Can I have a ride?” Thinking that Felix wanted a lift to his local housing, Bill was taken aback to learn that what Felix actually had in mind was a ride with us to Texas en route home to Lima, Peru!

page 13

That summer, chess was the craze, given the worldwide attention to the Match of the Century between chess Grand Masters Bobby Fischer of the U.S. and Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union, with serious national-pride implications. Hooked on the game ourselves—there was a lot of “chess” in tennis in the days of our wooden Jack Kramer Pro Staff racquets—we rigged up two small, magnetized chess boards, connected by wires to dry cell batteries and tiny lightbulbs.

Since Ed’s car was congested with four or five bodies plus gear, chess-nut Robert (“Spook”) Campbell [18] would ride in the trunk, passing the time by playing chess against those of us inside the car whereby we would signal our moves with an invented Morse code by light flashes!

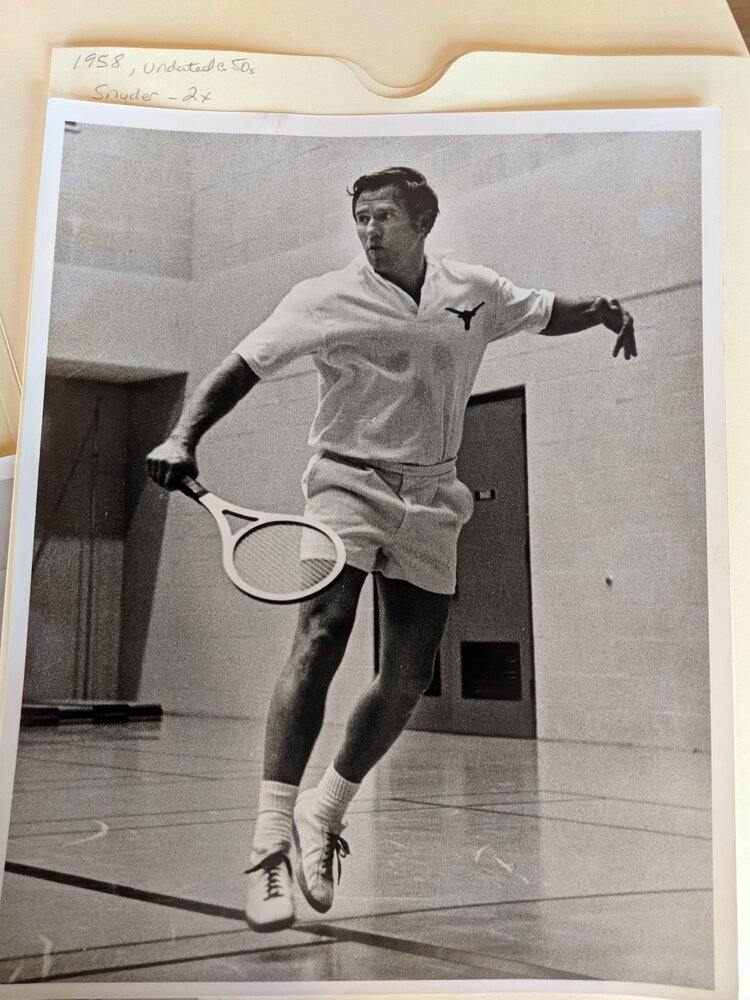

We were thrilled to get the news a few weeks later that our new coach would be Dave Snyder, the successful and highly respected head coach for 14 years at the University of Arizona, a perennial tennis power. Just as appealing to us were his Longhorn credentials on Dr. Penick’s teams in the early- to mid-’50s. He had won the Southwest Conference doubles title (with Sammy Giammalva) for UT in 1956 and had been elected as team captain.

My teammates and I had a sneaking suspicion that we were on the cusp of throttling up to a new level. We were bullish on the prospect, knowing that our ranks would be fortified in the fall with some outstanding freshmen from across Texas: Graham Whaling of Wichita Falls, Bill Fisher of Houston, both of whom I had known well for years; southpaw Don Murray of Fort Worth; and Dan Byfield and Paul Wiegand of Austin. Typical of Coach Allison’s collaborative style of leadership, he had sought our advice months beforehand on the best prospects in terms of talent and cultural compatibility according to the Penick-Allison template.

The Legacy of Dr. Daniel A. Penick*

During his time as coach from 1899 to 1956 (officially since 1908), Dr. Penick’s men won all ten of the Southwest Conference team titles awarded, took 31 of the 40 individual doubles championships, and captured 26 of the 40 individual singles championships. Not only that, his teams won five national doubles championships and two national singles championships. All told, apart from Wilmer Allison, the greatest tennis players in University of Texas history under Penick are chronicled in the photo montage to the right starting with Lewis White and ending with Dave Snyder.

* Enshrined in the Longhorn Hall of Honor.

LOOKING FOR BETTER IMAGES BUT THESE WILL HAVE TO DO FOR NOW.

The link to Part II of The History of Tennis by Jim Bayless is at

PART II -JIM BAYLESS – GAME, SET, MATCH COACH SNYDER (squarespace.com)