Julius Whittier – The Benchmark

MACK BROWN SAID ABOUT HIS LIFE JOURNEY, “WE ARE LIKE PIECES OF CLAY, AND EACH PERSON WHO TOUCHES US MAKES AN IMPRESSION. JULIUS DID SO ON MY LIFE JOURNEY.

WHO SOMEONE ROOMS WITH SHOULD NOT BE A NEWSWORTHY EVENT. HOWEVER, ON SEPTEMBER 8, 1970, THE ASSOCIATED PRESS WROTE A “PROVOCATIVE” ARTICLE THAT SAID, “WHITTIER, TEXAS BLACK OFFENSIVE GUARD, IS ROOMING WITH A WHITE PLAYER AND OCCASIONALLY DATING WHITE WOMEN.” I AM THAT “WHITE PLAYER.”

SINCE HE PASSED AWAY, SEVERAL NEWS ORGANIZATIONS HAVE CALLED ME REQUESTING AN INTERVIEW TO DISCUSS JULIUS WHITTIER. I DECLINED THOSE REQUESTS, AFRAID I WOULD BE MISQUOTED.

HOWEVER, I HAVE NOT BEEN SILENCED BY THE MEDIA, AND MY STORY IS MY REFLECTION POINT. THE WEBSITE IS FREE, HISTORICAL, INSIGHTFUL, AND EDUCATIONAL.

JULIUS WHITTIER IS A VITAL PART OF LONGHORN SPORTS HISTORY, AND HIS LIFE JOURNEY DESERVES TO BE CELEBRATED.

IN 1970 COACH ROYAL CALLED THREE SENIORS INTO HIS OFFICE AND SAID: “THERE ARE TWO TO A ROOM, AND ONE OF YOU THREE WILL ROOM WITH JULIUS.” JULIUS WAS MY ROOMMATE.

AS JULIUS AND I SOON LEARNED, WE HAD NOTHING IN COMMON EXCEPT THE LOVE OF FOOTBALL. WHILE JULIUS WAS A CRITICAL THINKER, I WAS NOT. IN ADDITION, CULTURAL PRISMS SEPARATED OUR LIVES. I WAS FROM WEST TEXAS AND VIEWED THE WORLD AS SIMPLE, UNCOMPLICATED, AND LINEAR. JULIUS WAS FROM SAN ANTONIO, AND HIS VIEW WAS COMPLICATED, THOUGHT-PROVOKING, DEEPLY PENETRATING, AND PERSONALLY INTRUSIVE. JULIUS FORCED ME OUTSIDE MY COMFORT ZONE, AND I DID NOT ENJOY IT. SO WE ARGUED, AND THROUGH THE PROCESS, I LEARNED MORE FROM JULIUS THAN JULIUS LEARNED FROM ME.

IT HAS TAKEN ME FIVE YEARS OF SOUL-SEARCHING AND RESEARCH TO COMPLETE THE STORY BELOW. IT IS A LONG ARTICLE THAT INTERTWINES LONGHORN’S RACIAL HISTORY WITH SPORTS AND SETS THE STAGE FOR NEW BEGINNINGS WITH THE BENCHMARK BEING -JULIUS WHITTIER.

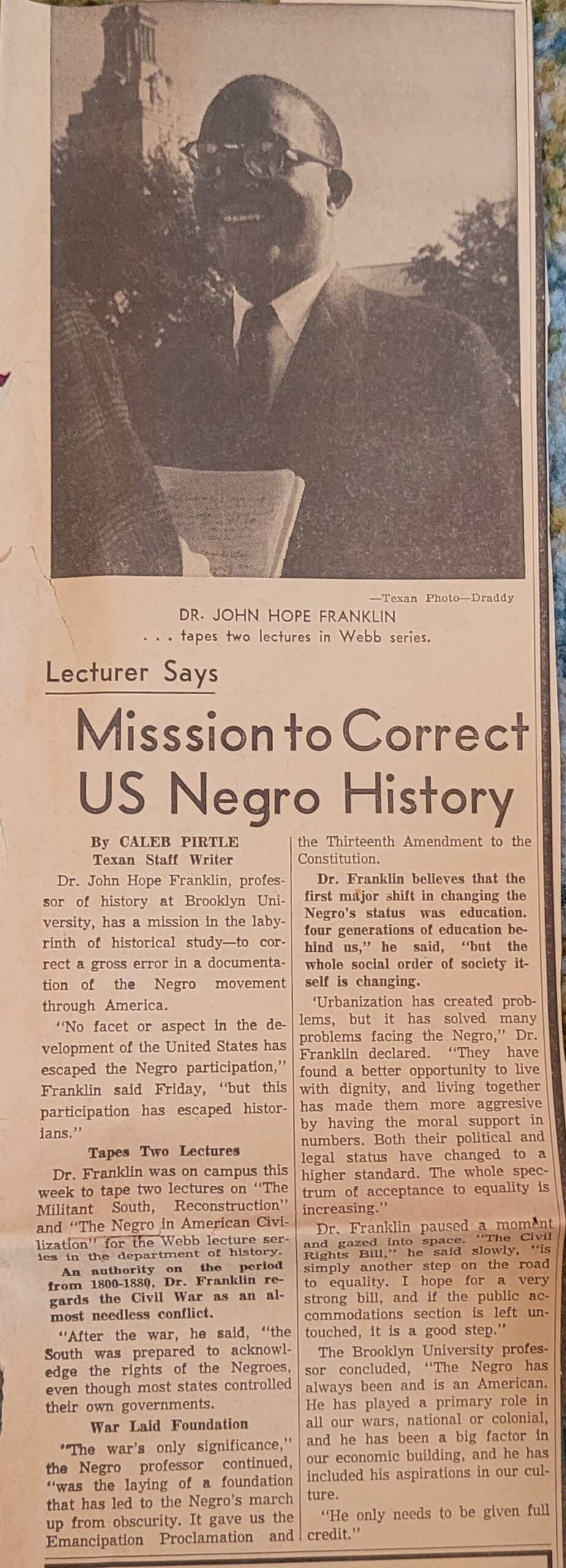

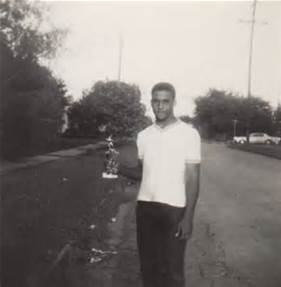

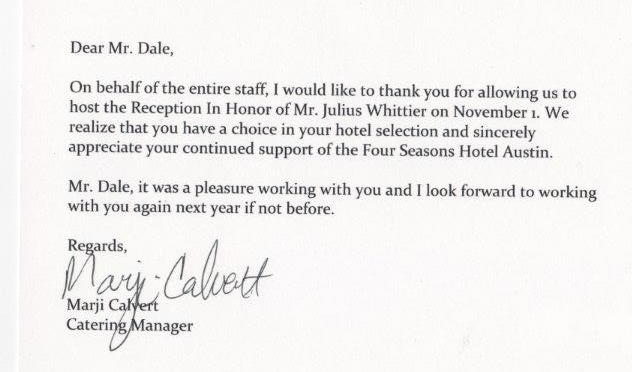

Vince did his thesis on Julius Whittier’s life and the small part I played in it. The photo below is after the interview.

IF YOU CHOOSE TO READ THE ARTICLE, PLEASE KNOW THAT I DO NOT PRETEND TO BE A PROFESSIONAL WRITER OR A PROFESSIONAL HISTORIAN. I AM NOW, AND I WILL ALWAYS BE AN AMATEUR WHO ENJOYS SHARING LONGHORN SPORTS HISTORY.

RESPECTFULLY, BILLY DALE

The Long Journey and It is not over

1913 the UIL stated that only white high schools qualified for league membership.

“ Even though we come from a racist past, we should be proud that we have created this University that attempts to collect all of what is known about us, our lives, and the world we live in and to preserve the thought and reflection of it for future generations. I am proud of that. I’m proud to have gone to THE UNIVERSITY.” Julius Whittier

THERE were MANY BLACKs BEFORE JULIUS WHITTIER WHO BUILt THE BRIDGE THAT JULIUS CROSSED IN 1969.

“Integration at UT came slowly, painfully, with much unnecessary resistance.”

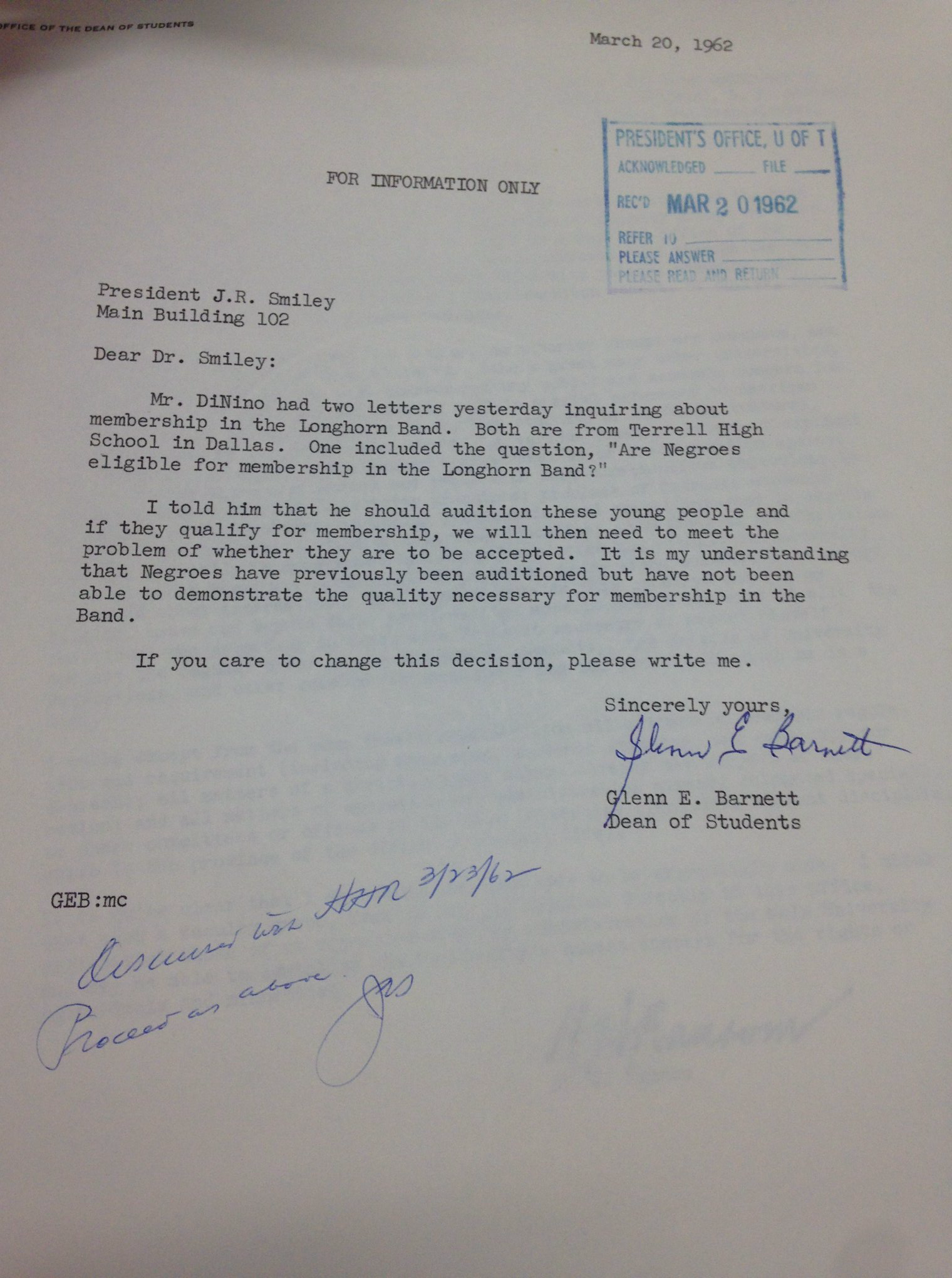

Some of their stories are shared on this website. There were documents written by large universities in the ’50s and ’60s that are racially incriminating. Two letters from U.T., one from A & M, and one from LSU, are shared below.

1938- George Allen tried to register for a Geology 601 class. He was accepted. He was hoping that Texas would refuse his admission so he could sue Texas. George said, “The only wrench in the whole machine is that they admitted me.” However, circumstances changed quickly, and the U.T. registrar’s office canceled his admission, so the original plan was back in play.

1946- African-American sues U.T. for access. Heman Sweatt is a qualified law school applicant. He held a bachelor of arts degree from Wiley College and had successfully completed 12 hours of graduate work at the University of Michigan. With the help of the NAACP, Sweatt spent years challenging the educational segregation policy. J. Frank Dobie sided with Sweatt and said to the state leaders we are more loyal “to prejudice and fanaticism than to Christianity or constitutionality.” In 1950 Sweatt won his right to attend the University of Texas.

1950– W. Astor Kirk entered U.T. graduate school, but he was told he would have to take his courses at the YMCA across the street from the Texas campus. Not caring to get into another court case, the university permitted Kirk to take classes on campus but seated him at the back of the classroom with a metal ring around his desk chair so his blackness did not rub off on the white students.

1954

1954 is the starting point for this article about Julius Whittier. Fifteen years after writing the 1954 document referenced below, Julius Whittier receives the second football scholarship presented to a black player at U.T. Julius but he will be the first African American to make the U.T. varsity football team. This was also the year that the first black (Duke Washington) played in Memorial stadium. His appearance at the game violated university rules since the Board of Regents didn’t drop the stadium’s color barrier until Texas hosted the 1957 NCAA track meet.

In May 1954, the Supreme Court ordered the integration of the nation’s public school.

Darren Kelly, a postdoctoral fellow in the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement who wrote his master’s thesis on the integration of Texas football, said several factors caused UT to delay the integration of its teams later than other schools. Texans tended to connect with their university through football, and some alumni exerted pressure on the university to remain segregated on the field. “Whether it was hesitation because of fear of losing money from boosters or lack of being able to get great white recruits who didn’t want to play with African-Americans, or fear from other fans or parents and players who didn’t agree with integration — all of these were factors,” Kelly said. “You didn’t want to rock the boat too much and lose support.”

In August 1954, Marion Ford Jr., a good student and athlete who wanted to major in chemical engineering and play on the UT football team, was admitted to the university along with four other African-Americans. The registrar, athletic director, and two members of the Board of Regents met to decide what to do. Ford had been admitted to UT, but the university still segregated its varsity teams. Their decision was to revoke the admission of all five students, making the athletic decision moot. Ford was angry and protested, but the decision stood.

He enrolled at the University of Illinois, where he did well both academically and on the football team. Ford transferred to UT in 1956, the first year African-Americans were admitted to the university as undergraduates, but he still wasn’t allowed on the football team. He graduated magna cum laude, earned an M.A. and a doctorate in dental science, and in 1963 received a Fulbright scholarship. But he never played football

1956– The University of Texas announced that the classrooms would be fully integrated. Texas was the first school in the South to adopt this policy. However, Royal believed that the UT regents just were not ready to integrate totally. Integration occurred in small incremental steps as permission, not a mandate to integrate. Dorms and dining halls were still segregated.

1959- The regents voted to provide on-campus housing for blacks attending summer orientation programs.

Early 1960’s

1961– April 27th, the Student Assembly voted 22-2 to integrate the dormitories.

1962- The Longhorn Band accepts Edmund Guinn as its first black member.

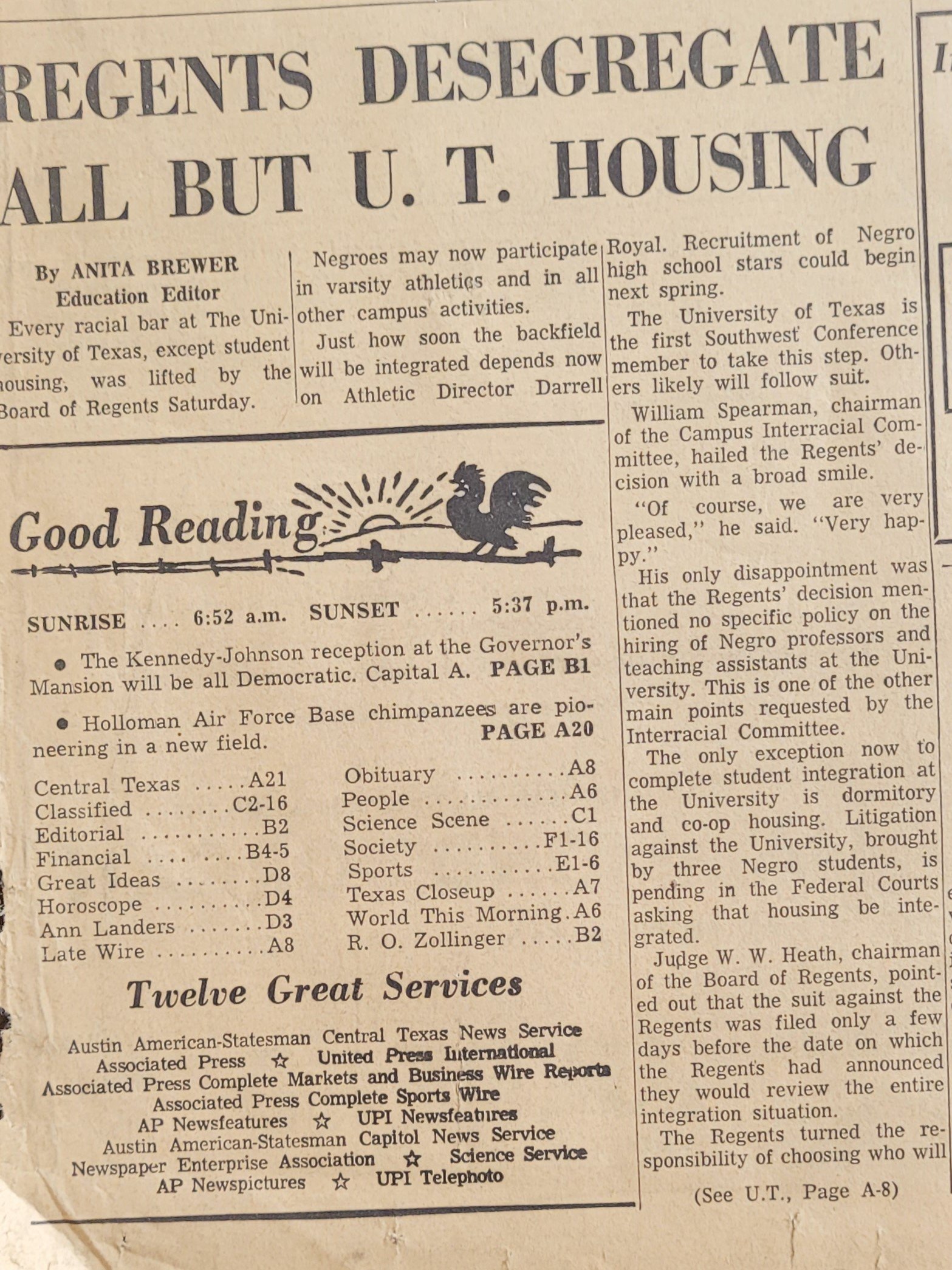

Author J. Brent Clark says in his book “Texas Caeser” that In July of 1961, the UT regents passed a resolution that housing was auxiliary to the educational process and not subject to campus integration. That resolution did not last. There were powerful forces working to desegregate all aspects of University life under the leadership of Governor John Conley, Frank Erwin, and LBJ.

By the early 1960s, a majority of students favored integration both on the playing field and off. In May 1961, the Regents received a Student Assembly and faculty petition with 7,000 signatures to support “the immediate integration of all housing and athletic programs.” A concurrent request from students opposing integration contained only 1,300 signatures.

1962

1963

The university’s first black varsity scholarship athlete was track star James Means, an Austin high school student who planned to attend UT in the fall of 1963. His mother, Austin civil rights activist and teacher Bertha Means, called Frank C. Erwin Jr., who was then a new member of the Board of Regents, to protest the fact that her son was ineligible for varsity track only because he was black. A few months later, the Board voted unanimously to integrate athletics, stating that extracurricular activities would be open to all students without regard to race or color.

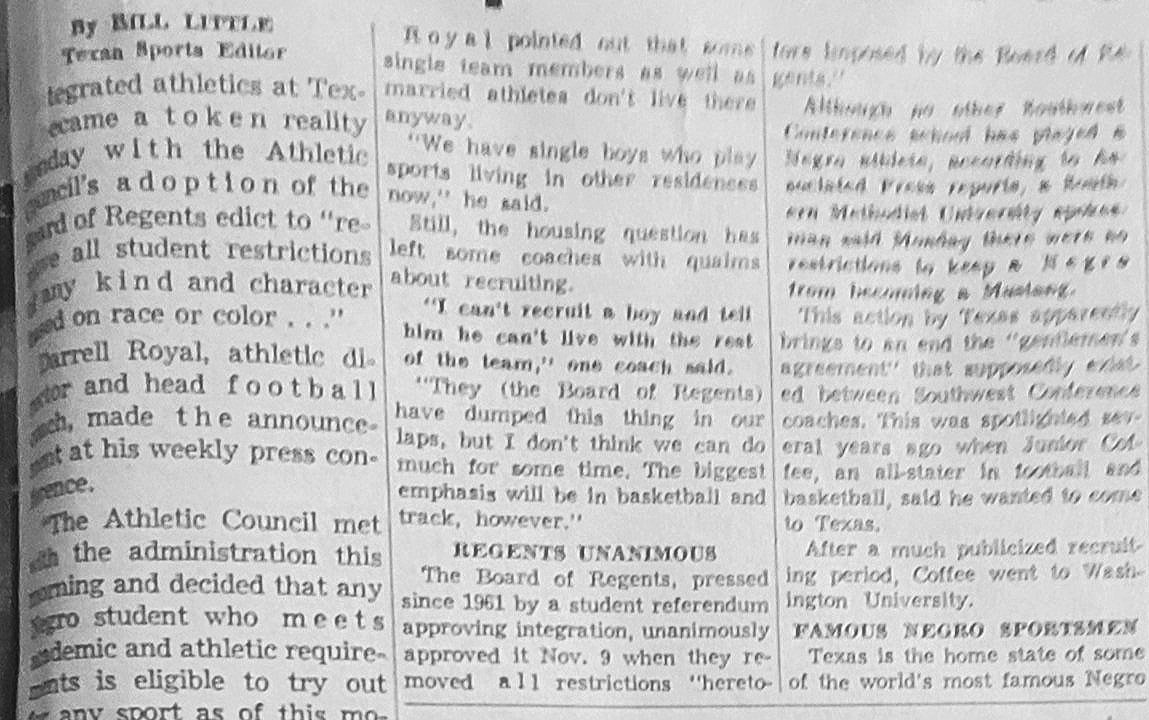

1963 -the University of Texas Board of Regents overturned a rule prohibiting black athletes from playing on various intercollegiate teams. James Means, Oliver Patterson, and Cecil Carter joined the track team as scholarship athletes. The first black (Gwen Jordan) was elected to the Student Assembly.

The University of Texas announced that everything on the campus was now open to all students. Did that also mean Texas athletics?

Royal says, “It might come as a shock to some people, but football coaches don’t decide when you integrate.” The Regents gave Darrell Royal, then-athletic director and football coach, discretion on when and if a black student might participate in a UT athletic program.

Royal offered football scholarships to black athletes, but none joined the team for various reasons. The racial issues continued to fester until 1969.

On 11/19/1963- the university’s board of regents desegregated all student activities.

1964

Texas set up Mexican-American study programs.

1964- Erwin Perry broke the faculty’s color line at UT. Perry was the best of a new group of engineers.

1965

U.T. officially integrates its athletic program.

1966

In 1966 Jerry LeVias was recruited by Coach Royal, but Jerry chose to integrate the Southwest Conference at Southern Methodist University.

In the book “The Big Shootout” by Mike Looney, Edith Royal says, “When Barbara Jordan (first black woman in the Texas Legislature) came to the lieutenant governor and governor and said ‘We’re not gonna vote for any more appropriations for the university until it’s integrated into sports,’ that’s when they got started on it,” revealing the bare truth of how and why integration came slowly to Longhorn football.

1967

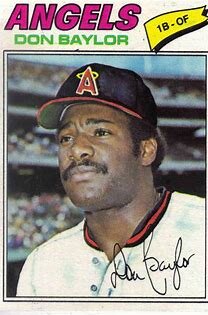

New York Times says, “In 1967, Royal and his staff recruited a local star named Don Baylor, a gifted baseball and basketball player. He grew up in West Austin during a time that downtown had separate water fountains for blacks and whites. Don integrated into his junior high school and dreamed of breaking the color barrier at Texas. Don Baylor wanted to play all three sports, something universities like Stanford, Oklahoma, and Texas Western would allow, but not Texas.

Royal wanted him to play football. Baylor never discussed with the public anything about the recruiting process with DKR, but Baylor did say, “they were relieved when the Baltimore Orioles drafted him.” Don Baylor said, “The Southwest Conference and U.T. were not ready to break the color barrier.” “The Orioles took the pressure off Texas.”

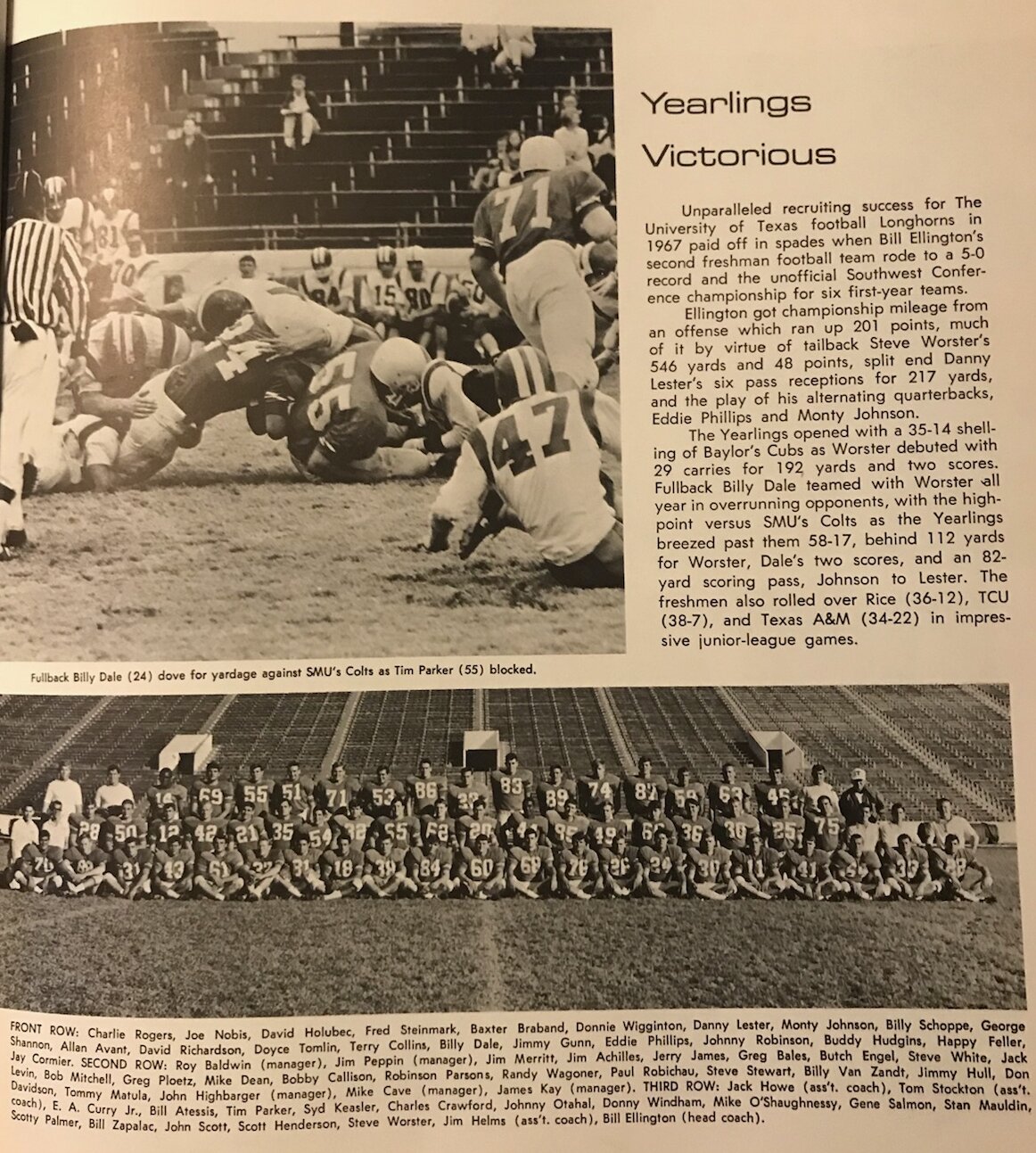

In 1967 two black students- E. A. Curry and Robinson Parson walked on. E.A. made the freshman team, but he struggled academically and quit.

E.A. Curry was a walk-on freshman from Midland’s all-black Carver High School, hoping to win a football scholarship, scores a touchdown in practice, the first African American to ever score a touchdown for Texas.

In the Fall of 1967 the Negro Association for Progress informed DKR they were not happy with the progress on integration.

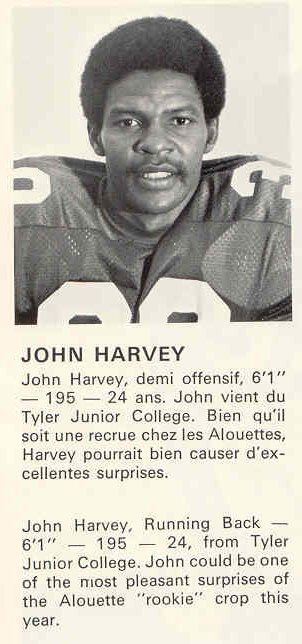

1967- John Harvey signed a letter of intent but never attended UT.

John Harvey was perhaps the most outstanding athlete ever at the original Anderson High School. Anderson had remained an all-black school on the east side even though Austin’s schools had technically been integrated since the mid-1950s.

Harvey signed a letter of intent to play football at Texas for Darrell Royal. However, he never entered UT, choosing instead to go to Tyler Junior College, where he became an All-American and later a star in the Canadian Football League.

1968- Leon ’Neal was the first African American awarded a full football scholarship to UT.

In the fall of 1968, Royal believed he had found the right young man to integrate his squad and signed tight end Leon O’Neal of Killeen to a scholarship.

O’neal says, “UT was and always will be a football school, and I loved that about them,” O’Neal said. “So when they wanted to recruit me straight from high school, I was not only excited but felt surprised since this was the first time UT had ever done anything like that.”

Headlines from all over the state, including the Killeen Daily Herald, touted the history-setting scholarship. Herald sports columnist Herb Gormley described the act as a good choice. “From what we have seen, Texas could not have made a better choice. … Leon was a team man, doing his job, a good one, in his quiet way.”

O’Neal played well on the freshman team, despite spending his first year in Austin under a microscope. It made news when he missed a practice, O’Neal recalled.

“I was coming home from the dentist when I hear on the radio I ran away from campus. I didn’t run away; I had to get my wisdom tooth out!” he said.

For the first time, O’Neal said he felt what it was like being discriminated against because of the color of his skin. “I didn’t get spit at or anything like that. But I had not as much help getting used to the campus as the other guys,” he recalled. “Yet on the field, we got along to get the win.”

O’Neal’s football career at UT ended with an ankle injury and the loss of his scholarship due to academic probation. But he transferred to Southwest Texas State University (now Texas State), played on one conference championship team, and led the nation in interceptions in 1972.

In 2005, he was inducted into the Texas Black Sports Hall of Fame.

“My dad’s story is one where every time you see an African-American football player at UT, you can say. ‘You would not be here if it wasn’t for my dad,’” Leon O’Neal III said. “My family and I are truly proud of his legacy.”

The barrier O’Neal broke at the University of Texas helped change the face of athletics in the South, and O’Neal will always be grateful for the opportunity. “If it wasn’t for my faith, and my upbringing none of this would happen. None.”

Article from Killeen Daily Herald by Monique Brand – Herald correspondent

In 1970, he was a junior college 1st team All-American at Tyler Junior College in Tyler, Texas.

He burst into the CFL with the Montreal Alouettes in 1973. Rushing for 1024 yards, with an incredible 7.5 yards per rush average and 32 pass receptions, he was an all-star and won the Jeff Russel Memorial Trophy, being runner-up as CFL MVP.

Like many other players lured by the big money, he jumped to the World Football League in 1974, playing two seasons with the Memphis Southmen. In his first season, he rushed for 945 yards, caught 21 passes for 275 yards, scored five touchdowns, and threw three passes (one for a touchdown.) In 1975, rushing behind future NFL Hall-of-Famer Larry Csonka, he gained 137 yards, caught eight passes for 107 yards, scored four touchdowns, and threw two passes (1 for a touchdown.) In the short history of the WFL, he was 13th on the all-time rushing list, with 1082 yards.

When the WFL folded, he returned to the CFL, playing ten games for the Toronto Argonauts in 1976 (rushing for 68 yards, catching 26 passes for 459 yards, and five touchdowns) and one game for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats in 1977.

The recruiting of Julius Whittier

Julius Whittier says:

Quotes from Julius and Leon were taken from Texas, Our Texas

in the middle of winter January 1969 I rode a greyhound bus to Austin. Leon O’Neal met me at the station. Leon was one of the most disarming and friendly people anyone could know. He was the best possible guy to show me around the Texas athletic department and facilities.

Meeting Leon had as much to do with my going to Texas as the fact that Texas was competitive nationally in football. I didn’t think there was any leverage from the outside to force Texas to change to an integrated football program. Besides the first step toward change would be for blacks to accept scholarships show up and seriously compete for starting positions. My own experience may be important to an assessment of that big step. However the experience of EA Curry, Roosevelt leeks, Lonnie Bennett, Fred Perry, Donald Early Howard Show and every other black who has been through the Texas football program including Heisman Trophy winner Earl Campbell are equally important.

Leon told me how important it was for people like me who were offered scholarships to accept them in order to get blacks on the rosters of Texas football lettermen. Yet this opportunity was being overlooked by black athletes. Leon was very honest with me he said that dorm life would be comfortable but easy to get enough of .

He said that with all of these different guys from towns all over Texas there would be something happening all the time from a quiet studying and television watching to well…. just about anything. Getting along with the white football players would not be much of a problem Leon said because most of them did not have a problem with having black teammates. Of course there would be some guys who would but there would be guys like that anywhere I might go.

Leon pointed out that what commanded the most respect from teammates was showing everyone coaches and players alike that you took care of business on the football field. After Julius had his meeting with Darrell Royal he was convinced that he wanted to be a Longhorn And on February 11th 1969 Julius signed the Southwest Conference letter of intent declaring that he attended to accept the scholarship offer from Texas.

1969

In 1969, DKR offered scholarships to Jon Richardson( who became a Razorback) and Julius Whittier. Leon O’Neal showed Julius around the Texas campus during his recruiting trip, and Leon shared with a smile on his face that white folks were ok.

1969,1970,1971 Basketball

Sam Bradley was on the freshman track team and Leon Black ask him to join the basketball team. He Is the First African-American to play basketball at Texas.

Sam Bradley Is also the First Black Athlete To Letter In Basketball At Texas.

Coach Black worked hard to get Blacklock to come to Texas, and it was big news when he signed.

Quiet, even-tempered, and dedicated to the game, Blacklock was perfect for his historical role. He quickly established himself as a starter and finished his junior season as the leading scorer for the 1971 squad, averaging 17 points a game.

Jimmy Blacklock transfers to Texas and leads the basketball team in scoring.

Never mind his numbers, Blacklock proved his true value when, through a vote of the players, he became the first black athlete to be a team captain on any UT team.

1971

In 1971 there were 289 black students and 1283 students with Spanish surnames attending UT. Texas leaders decided to establish a compensatory program to help culturally denied black Americans and Mexican Americans a better chance of attending Texas.

The Board of regents said that this compensatory program was unfair and prejudiced. While Irish, Scotch, Yougoslave, Japanese, Chinese, Italian, French, and other descents were denied entrance due to Texas academic standards, African-American and Mexican-Americans who also failed the same academic standards were admitted.

1971 Carl Johnson’s Struggle For Equality

Carl says

“They Keep Telling Me Things Are Getting Better,” Johnson said. “Well, Sure, They’re Getting Better, But When You Want Something Real Bad, You Don’t Want To Wait 20 Years For It.”

Byrd Baggett shares Carl Johnson’s story at https://www.texaslsn.org/byrd-baggett-carl-johnson-track-lost-too-soon

1972 – A Season of What Could Have Been

Larry Robinson is the first Black athlete who signed a letter of intent to Texas. On The Freshman Team he Scores 55 Points And collects 28 Rebounds In A Win Over TCU.

1972

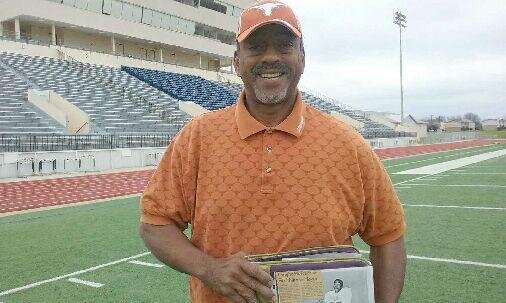

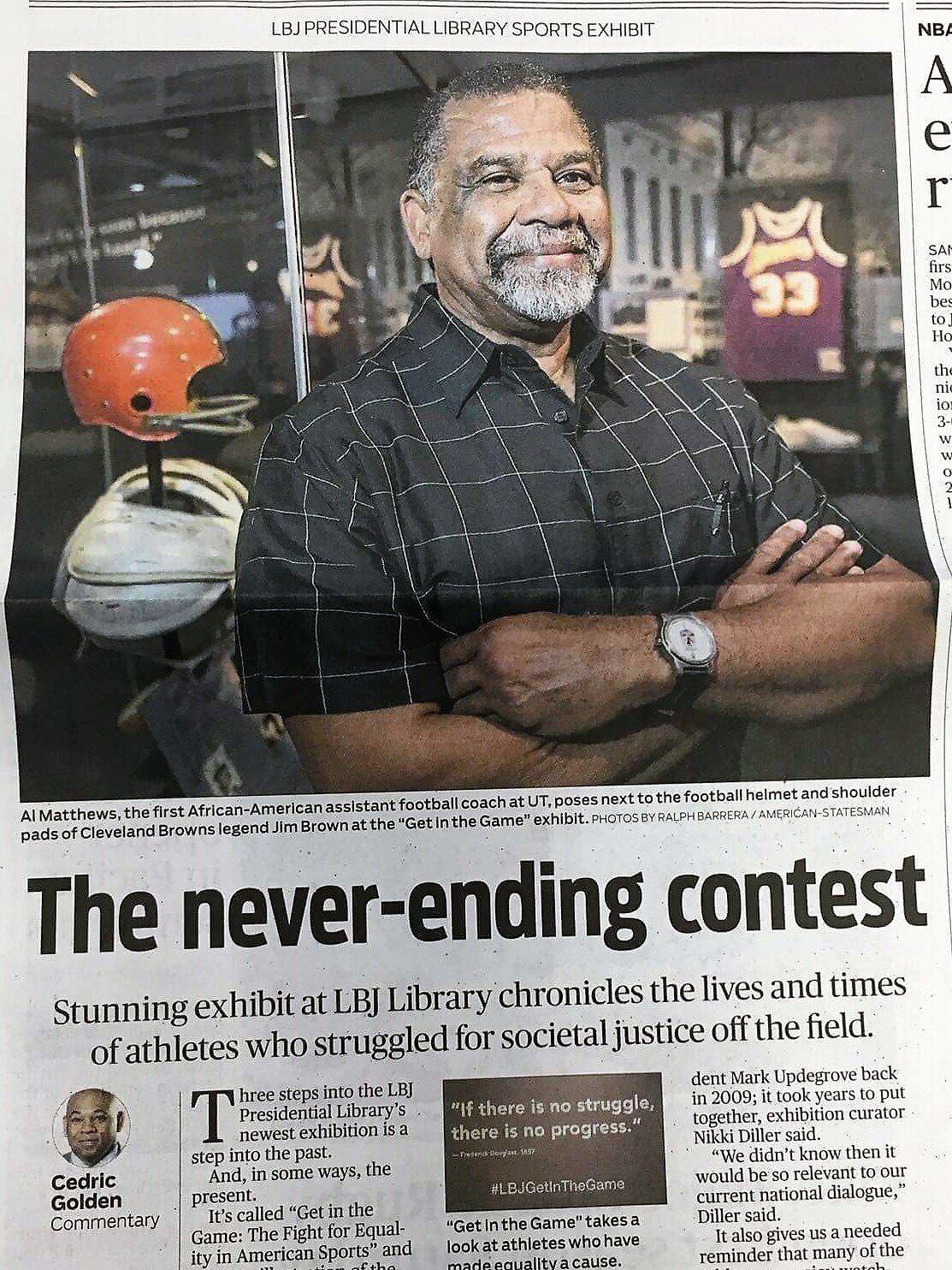

Al Matthews is the first African-American football coach at the University of Texas.

Lonnie Bennett is the first African American to score a touchdown on the varsity.

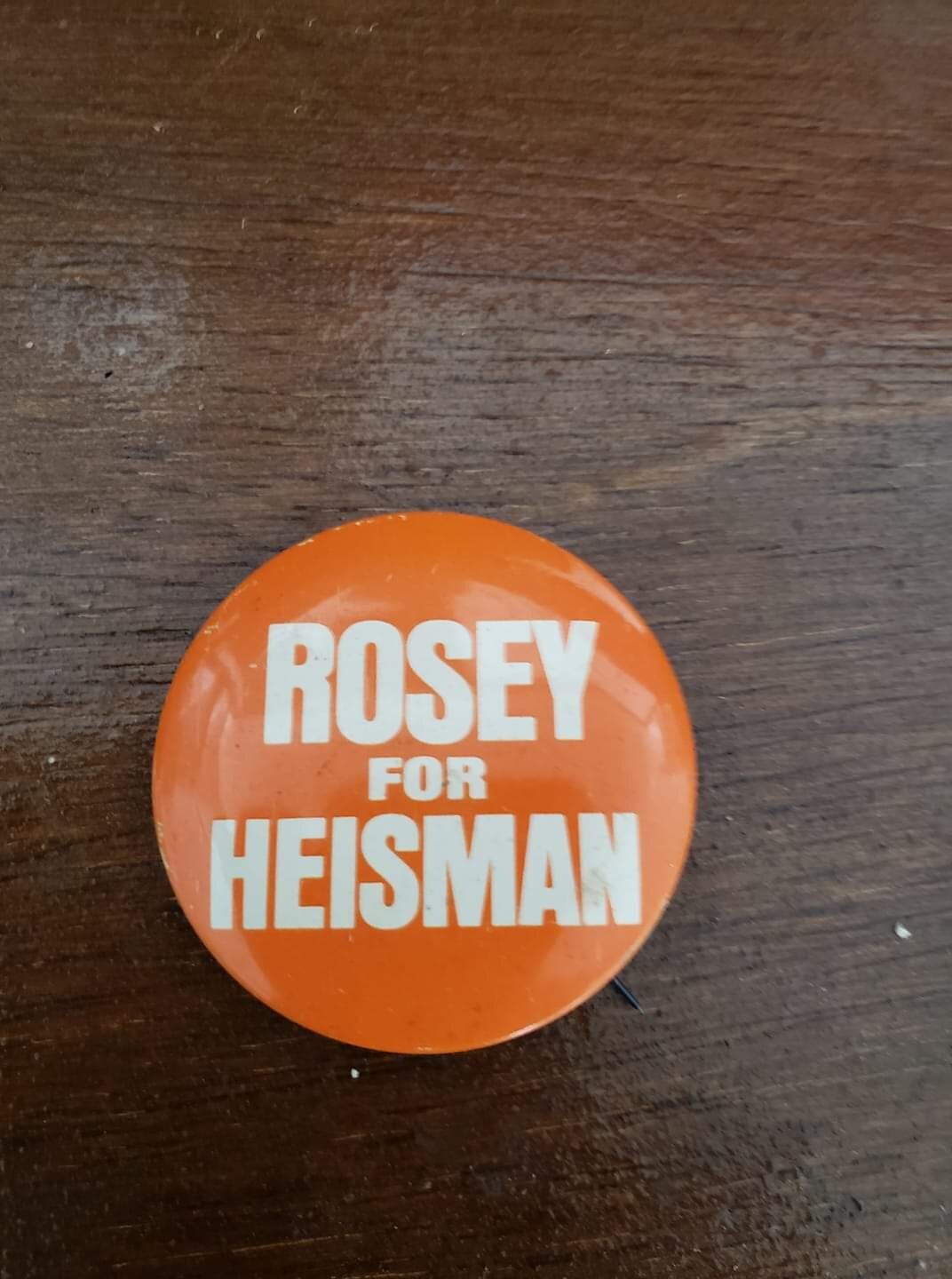

1973 Roosevelt Leaks First black Longhorn All-American

In 1973, UT had 412 black students and 1,600 Mexican American students enrolled of 41,000 students.

Rosy says in the book. What it Means to be a Longhorn, “ Being one of a small number of African-American students on campus, there were issues that happened on and off the field, but they were some of the same issues I’d faced in high school. “…….”It was just a matter of whether or not You could tolerate it.”

“I knew I would be looked at closely because I was black, and it was not an easy chore. But it was nothing unusual. It was no different from the way it had been in high school. We had been dealing with it all of our lives, and we knew how to handle ourselves.” Royal says, “Roosevelt Leaks ….did more to kick down doors and break barriers than anyone. Earl knew that he could be at Texas and be a star. which blacks didn’t know until Rosey came.”

1976

Gralyn Wyatt was the first black baseball player at Texas as a walk-on, but he never lettered (looking for photo).

Andre Robertson, in 1976 was the first black baseball player to receive a scholarship at Texas, and he had to endure racist slurs from fans in a still tense time in American history.

Andre Robertson was a trailblazer for The University of Texas baseball program. He was a standout infielder for three seasons with the Longhorns, lettering each year from 1977-79.

1990

The fight against racism takes slow, incremental steps forward for decades. Still, in 1990, with only 3.7 percent of the student body of Afro-American heritage and half of the football team black, there was a significant racial confrontation that set back race relations.

In Eric Metcalf’s senior year, he received no awards or honors. By many, not honoring Eric was perceived as racist by team members and some high school recruits. Also, there is only one black assistant coach, no black administrators, no black trainers, no black managers, and a minimal number of black professors. Many wondered why?

Johnny Walker’s father did not want his son to go to Texas to play baseball and football because he thought U.T. was a racist institution. Walker experienced one racial slur, the “N” word, while playing baseball for the Longhorns.

Donna Lopiano says, “I don’t think there are enough black anybody.” We have a real credibility gap … I believe that people are trying hard to make sure this place is not racist, but systemic racism is part of bureaucracies that move as slow as a large dinosaur.”

These unanswered questions and comments listed above, followed by offensive racial slurs against blacks during Roundup, raised its ugly fraternal head and justifiably angered the black Longhorn student population. President Cunningham tried to resolve this battle before it became a war.

Coach McWilliam canceled one day of spring practice to let his players march on the campus’s West Mall to protest the racial slurs. President Cunningham also was there to deliver a 6-page speech that was ultimately rejected by those who attended. He was told that his speech had no value. The protestors wanted dialogue, not rhetoric. In the book “Bleeding Orange,” the authors Kirk Bohls and John Maher summarize Cunningham’s speech as vague and bureaucratic; if anything, Cunningham’s speech just reinforced the university’s aloof image that U.T. has been trying to shake for decades.”

Perhaps to save his credibility, President Bill Cunningham later suspended the Fraternities involved in the racial event.

Julius Whittier’s UT journey started in 1969. Julius has received the most national exposure for his place in Longhorn Sports History, but as outlined above, there were many before him who built the bridge that Julius crossed.

Julius Whittier’s journey by Billy Dale

On September 8, 1970, the Associated Press wrote a “provocative” article that said, “Whittier, Texas black offensive guard, is rooming with a white player and occasionally dating white women.” I am the “white player.”

In 2013 Julius was in Austin on business and spent the night at my home. Vince Young called me and asked if he could visit and interview Julius and me for his thesis paper. He wanted to relate our story as roommates in 1970 to the present state of racial relations. Here is our picture after the interview.

Julius Whittier, Vince Young, and Billy Dale

JULIUS WHITTIER SAYS TO BILLY DALE “I WAS JUST TRYING TO MAKE YOU THINK.”

Living with Julius was both challenging and a blessing.

In October of 1970, Julius Whittier, after “lights out,” chose to engage me in an argument about mortality.

Julius said, “Billy, I’m never going to die,” and you are.”

I told Julius that was a ridiculous statement, but he continued to push me on the subject.

I got so frustrated with his argument that I leaped out of bed and jumped on top of him, pointing my finger at his face and saying, “It is people like you who give your race a bad name.”

Julius pushed me off him, stood beside his bed, and returned the pointing finger saying “Did you think I was serious”? I said, “yes,” and Julius responded, “I was just trying to get you to think.”

He accomplished his goal. I learned more about life through Julius’ eyes in 6 months than I ever learned in classes at Texas. Julius challenged me to question conventional racial wisdom with the reality of a changing world.

In the book Horns, Hogs, and Nixon Coming by Terry Frei, Julius says he was on a mission to play football first. Still, he was troubled by his teammates insulating themselves from important political, racial, and war issues facing the country. Meaning that his teammates weren’t out to change the world in any way. From my perspective, as the webmaster of this site, that is a true statement. Julius said that he was into social change, but his Longhorn teammates had no clue there were any problems.

Billy Dale , Julius Whittier, and JoEllen Dale in 2013 at Julius party after his induction into the Hall of Honor.

Julius was troubled when the expansion of Memorial stadium caused environmental changes to Waller Creek and the destruction of many beautiful old trees. Julius felt that he was part of the problem. The system he was playing in was the reason for all the destruction. On the other hand, his teammates just shrugged their shoulders and wondered why they protested over a few trees. Julius said, “They were about playing football and stepping into the life that a solid football career at a solid football school gets you.”

Most of the time, our “discussions” were based on cultural differences caused primarily by how we were raised as boys. We verbally fought like siblings, but in the end, we formed a lifetime friendship built on our love for Texas, a team bond, and mutual respect.

I am proud of Julius more for his intellect, strength of character, and resolve to challenge the University of Texas “group think” than his football skills. He was the right person at the right time to break the color barrier in Longhorn Texas football history.

Since his death, the media has written volumes about Julius’ life, but they write from a distance while I write as his roommate, who shared many “pointing finger” moments with him. As I reflect on Julius’s life journey and that one night when he told me he would never die, I now understand his comment about dying (you see, he taught me to think, after all). His legacy will never die; in that sense, Julius will live forever.

Julius Whittier – The rest of the Story

This article’s research is derived from living with Julius Whittier, an article by Stephen Ross dated Nov 14, 2012, a link to the following site http://www.youplusdallas.com/cityblog/sports/2012/11/julius-whittier-darrell-royal-changing-the-face-of-texas-football/#sthash.pTnyiuA9.dpuf and an article written in the New York Times called Changing The Face Of Texas Football.

Julius roomed with another black his freshman year, but he was the only black on the team by his sophomore year, and Coach needed a roommate for Julius. As in all sports, seniors are the team leaders, so Coach Royal decided a senior could help facilitate Julius’s transition to the varsity. Coach asked three seniors on the team to his office and asked one of the three to room with Julius.

Julius was a high thinker most of the time.

Julius had one regrettable low-thinking moment that could have been explosive. He said, “Texas seems to recruit a lot of boys from small towns, and most of them have small minds just like their fathers.” History says Julius was wrong in making that statement. I can confirm that most of the young small-town boys welcomed him to the team. Julius never mentioned to me the name of one team member who made a blatant prejudiced remark that precipitated his comment, “minds just like their fathers.” As far as I know, no one on the team ever challenged him for making that statement. Years later, Julius conceded to me that comment was wrong.

That is not to say that prejudice did not have a home with the Longhorns. Julius says he was never exposed to any outright racist outbursts from teammates, but he did recognize teammates’ slights. He was never invited to parties with his teammates, and though racial slurs were never directed at him, Whittier heard them when his fellow Longhorns forgot he was in the room.

Recruiting of Julius and Beyond

Steve Barton

Billy,

I am sure you do not remember me, but I walked on in 1970 made the team and Lettered at fullback my Freshman year behind Gaspard. I roomed with McEnvale (Not the Mattress Mac) but ended up rooming with Julius for a few months. I remember you and Julius coming to the room and giving me the Freshman once over. Nothing bad. Julius was a funny, likable person with many girlfriends. I was often his receptionist, relaying phone calls to the room for him from dang near all girls of all races. During Spring practice, I was working as a fullback on the attack team against the first-team defense and made a lucky block on Randy Braband. Coach Door grabbed my face mask and asked me my name. I told him, Henry Barton. The next day, I had a white jersey and reported to Coach Ballard. I was way over my head and nervous, but I think at the time, Bobby Callison was hurt, and I actually scrimmaged at fullback with Eddie Phillips at QB and Burtelson and Don Burrisk at running backs. My speed was not world class and I remember Julius started calling me speedy. We only roomed together for a few months, and I know you were close, and I think that is when he moved in with you. I actually don’t remember if I changed rooms or if he moved out. I hurt my knee the week before the Spring game and ended up having to have surgery. That is when Coach Ballard told me the scholarship we discussed was out the window. I moved out of Jester in a few months and rented a house with Rick Vacura, who had also had knee surgery.

I did not mean to make this a book but just wanted to relay my fond memories of Julius and thank you for all you do for this great site.

Thank You

Steve Barton

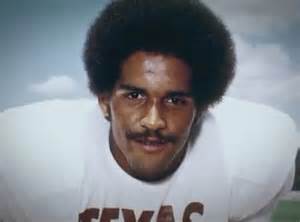

Defensive coordinator Mike Campbell recruited Julius Whittier. Julius says, “If you know Mike Campbell, you know that he was not a man of any finesse, except when it came to designing defenses. He said what he meant and meant what he said,” Whittier said. “He convinced me that I would get a fair shot.” Whittier also ask Coach Royal if he would get a chance to start? Everyone gets a chance to start at Texas, but you must earn it,” said Coach Royal. Coach does not “give” anyone a starting position. Julius was the first black starter in Longhorn football history.

Royal said, “I knew he could play for us and handle any difficulties off the field.”

Julius confesses that breaking the racial barrier at UT was not his primary goal. He says, “I was a jock, plain and simple,” he said. “I didn’t care about civil rights or making a mark. I just wanted to play big-time football.”

However, Julius was not naïve about racial issues. He said, “I soon found out that there were probably a lot of racists on campus, but there were far more people who gave a damn about you as an individual as opposed to the color of your skin.” He soon learned that UT was not a racial madhouse.

Julius says he never felt pressure as the first black varsity football player at Texas. He said he was too busy wrapped up in the events of each moment, class, workout, dinner, study hall, practice, and friends. “I had no real-time or hard-drive space in my brain to step back and worry over how potentially ominous it was to become a black member of the University of Texas football team and all of the horrifying things that, from a historical perspective, could happen to black people who dare to accept a role in opening up historically white institutions.”

Whittier only had one serious run-in with Coach Royal, and it was over an AP article written that suggested that Coach Royal and his coaching staff were racist.

Royal and Whittier in conflict

In 1972 Robert Heard co-authored a 5 part AP series on recruiting blacks. Even though in 1972 there were 7 African American players on the Longhorn team, Texas was not able to recruit one black player in 1972. Robert Heard says, “Royal had tried to recruit blacks, but the “image” (of being a racist school) fed upon itself and reinforced the difficulty” of recruiting African American athletes. Alfred Jackson confirms Heard’s comment- “Everyone told me that the University was not a good place for me because Texas hadn’t recruited many African Americans and that it would be a hostile place for me to go.” “My mom never believed that; she just believed in David McWilliams.”

It did not help that the AP articles quoted 6 Longhorn players saying they felt there was some racism among the Coaches. One of the 6 was Julius Whittier. In Jimmy Banks’s book The Darrell Royal Story, page 156-159, Jimmy relates a story about an interview written by AP that quotes Julius as saying some unflattering things about UT. After reading the article, Julius visited Coach Royal and said, “the interview was a “pressure cooker” and “I (Julius) was really trying to help (UT) but was clumsy.” Royal responded, “If you were trying to help, you really were clumsy.” Eventually, the matter was dropped, and Julius continued to remain in the starting lineup. Excluding this incident, Julius and DKR had a close relationship during and after Julius years at Texas.

Piling on Royal, Meat on the Hoof, written by Gary Shaw, also made some unmerited accusations about DKR. It was apparent that Gary Shaw had been radicalized. There had never been a book like this written. George Sauer, a member of the 1963 Longhorn national championship and the New York Jets Super Bowl National Championship team, endorsed the book that portrayed DKR as a fraud. Shaw accused Royal of building a regimen that demeaned athletes, instilled fear, ignored human rights, implemented academic deception, and supported racism. I know first hand these accusations by Shaw and endorsed by Sauer were in 2020 parlance “fake news.” Royal was no saint, but he did not deserve these accusations.

After graduating Julius said, “the further his UT playing career receded into the past, the more he appreciated his head coach.’’ “He made a difference in black athletes having access to play football at a top-notch University. “There were alumni and regents – I don’t know who they were, but I do know for a fact that there were alumni and regents who did not want black kids on this campus. Coach Royal bucked that. That’s one of the things I admired about him; he was a man who had his own independent image about what was right and wrong.”

Julius was interviewed by KUT and expressed his deep affection for Coach Royal. “I had a great time at UT. I got disciplined at the right times because I was into stuff. Being under Coach Royal’s eyeball, I needed to watch what the hell I was doing… Coach Royal will be missed. He was a mountain of a man. He had a big view of the world, and I was glad to be a part of his program. I love him.”

These last few quotes are taken directly from the KUT podcast.

Julius had command of the English language, and his keen insight was newspaper QUOTABLE.

Whittier said he turned two personal flaws into powerful tools of perseverance. He was confident to the point of cockiness and had a gift for oratory that served him well as a trial lawyer. “I had a mouth that I ran a lot and coherently,” he said. “It sounded like I knew what I was saying, and that protected me.”

President Johnson invited Jerry Sisemore, Alan Lowry, Randy Braband, Julius Whittier, and Roosevelt Leaks to his ranch. During lunch, President Johnson discussed the LBJ School curriculum with Julius and asked him to consider the School after he graduated from UT. Julius said, “that’s when I first learned what the LBJ School was all about. Julius said that, “the president told me specifically that he would enjoy knowing that I had at least examined the School’s program.” After finishing his undergraduate degree, he attended the LBJ School.

Julius received 3 degrees. An undergraduate degree in Philosophy from Texas, a graduate degree from the LBJ School, and a law degree from Texas. He retired from Dallas District Attorney’s Office as a chief supervisory prosecutor in 2014.

Julius said that it was “fairly easy” to determine a motive as a prosecutor for violent crimes. “Greed, passion, relationships with other people, appetites out of control, depression, low self-esteem, people wanting more than they make: all the things the Greeks wrote about 3,000 years ago.”

AUSTIN, Texas– December 1, 2010– LBJ Alum Julius Whitter (’76), The First African-American To Play Football For The University Of Texas At Austin, Recently Spoke To Current Longhorn Football Players,

Photo to the left- Coach Brown invited Julius to speak to his team in 2010. Coach said ‘We are so honored that Julius would come out and meet with the players,” “He’s a hero. He’s a pioneer. Thank goodness it is a much better world than it was in 1969 because of people like him.”

Julius through the years

Many of the photos in the following edited article were added by Billy Dale. Please google “Changing the Face of Texas Football” to read the original article.

Changing The Face Of Texas Football New York Times Article

By DEC. 23, 2005

AUSTIN, Tex., Dec. 16 – It was Dec. 6, 1969, and Julius Whittier was stretched before a television in the lobby of the jocks’ dorm, Jester Hall, when the euphoria of a heart-stopping victory lifted him, and most University of Texas students, outside onto Guadalupe Street. Texas had just beaten Arkansas, 15-14, in Fayetteville in what had been billed as the Game of the Century.

President Richard M. Nixon appeared in the locker room to declare the undefeated Longhorns as national champions. Whittier was a member of the Texas football team, but as a freshman, he was not eligible to play varsity at the time.

He was also the only black football player at Texas. As Whittier pinballed amid the revelers on the main drag here, he had an epiphany, one about the unifying elements within football that he would lean on for years.

“I had never experienced the exhilaration and joy of celebration where I was participating with what looked like millions of other kids my age,” Whittier recalled recently at his law office in Dallas. “It did not matter that they were almost all white.”

Neither Whittier nor anyone else knew that the time-capsule moment they were celebrating would become an inglorious milestone: the 1969 Longhorns were the last all-white team to win a national college football championship.

When Texas was co-national champion with Nebraska the next year, Whittier was a backup offensive lineman and the Longhorns’ first black letterman. He acknowledged that he had endured indignities but said his life experiences were expanded as much as those of his white teammates.

By playing at Texas, Whittier received advice from former President Lyndon B. Johnson over lunch at his ranch and learned to love Willie Nelson’s music.

Whittier, however, is intensely interested in the Jan. 4 Rose Bowl, the national title matchup between defending champion Southern California and Texas. He is proud that about half of the Longhorns’ roster players are black, including the star quarterback Vince Young.

“It completes the circle from a team that had no blacks to a truly diverse one, one with a black athlete in the ultimate leadership position — quarterback — of the university’s most prized institution,” Whittier said.

In the South, however, all-white teams were the norm into the late 1960s as the region was slow to embrace civil rights, especially in something as cherished as college football. Coach Royal recruited Jerry LeVias, but Jerry chose to integrate the Southwest Conference in 1966 at Southern Methodist University. In December 1969, with Nixon in the stands, the top-ranked Longhorns faced another all-white team in No. 2 Arkansas, a Southwest Conference rival.

“How’s that song go?” said Darrell Royal, the Longhorns coach who won three national titles from 1957 to 1976. ” ‘Things they are a-changing. But they weren’t changing that quickly around here at the time.”

When Royal arrived here, he was 32 and fresh from head-coaching stints at the University of Washington and the Edmonton Eskimos of the Canadian Football League. He had coached black players at both stops.

In 1967, Royal and his staff recruited a local star named Don Baylor, a gifted baseball and basketball player. He grew up in west Austin, knowing that downtown there were separate water fountains for blacks and whites, had integrated his junior high school, and dreamed of breaking the color barrier at Texas.

Chairman of the Board of Regents Frank Erwin pressured Royal to recruit black athletes. At the same time, Royal struggled to convince the big donors composed of oilmen, industrialists, and politicians to Recruit black athletes. Royal was on shaky grounds. Frank Erwin was weary of Royal’s failures to follow orders and wanted the coach fired. Many from the donor class and other influential friends of Royal had to defend him. For the remainder of Royals’ years as coach, supporters practiced damage control. The University of Texas publicity machine had to work overtime to support Royals’ image.

in 1969 Royal signed Julius Whittier to a letter of intent to play football for U.T. Royal described Whittier as “smart and tough and a heck of a football player.” He added, “I knew he could play for us and handle any difficulties off the field.” Whittier was a star at an integrated high school in San Antonio. His father, Oncy, was a doctor. His mother, Loraine, was a school teacher and a community activist who protested against a local grocery chain that prohibited black women from becoming cashiers. Whittier said his uncle Edward Sprott was head of the N.A.A.C.P. in Beaumont, Tex., and had not been intimidated when his house was bombed. Julius said his older brother, also named Oncy, had his head cracked open by police officers for his involvement in a guerrilla theater troupe that performed pointed skits about prejudice in San Antonio’s streets.

Whittier’s had success on and off the field — he was a three-year letterman and a starter his junior and senior year. His success paid immediate dividends for Texas. Roosevelt Leaks joined the Longhorns in 1971 and Earl Campbell in 1974.

President Johnson did his part in recruiting black athletes to Texas. Johnson sometimes would land by helicopter on the lawn of his presidential library and tell the prospective players why they should play for Texas.

50 years after Whittier as a freshman watched his white teammates defeat Arkansas on T.V. and win the national championship, and much has changed. However, some issues still conflict with the Texas football program. In 2020 the changes continued. Julius, Royal, and all the coaches except Akers on the 1969 and 1970 national championship teams have passed away. Royal, before his death, expressed regrets that he did not integrate his teams earlier. Many of us share that burden of guilt.

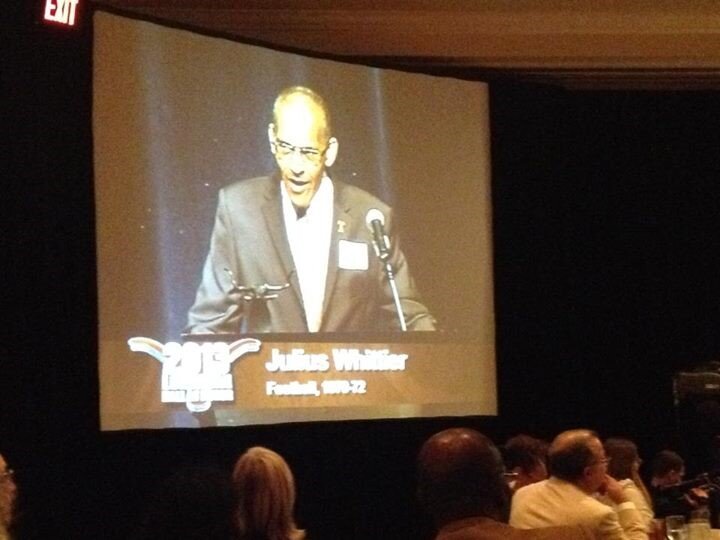

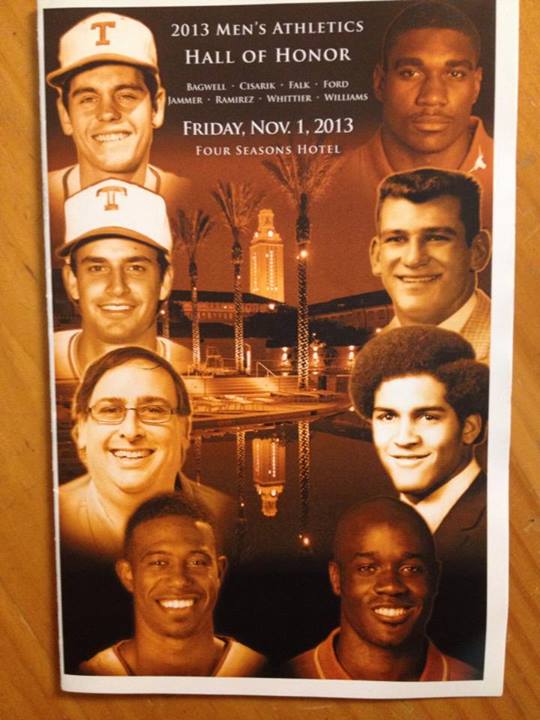

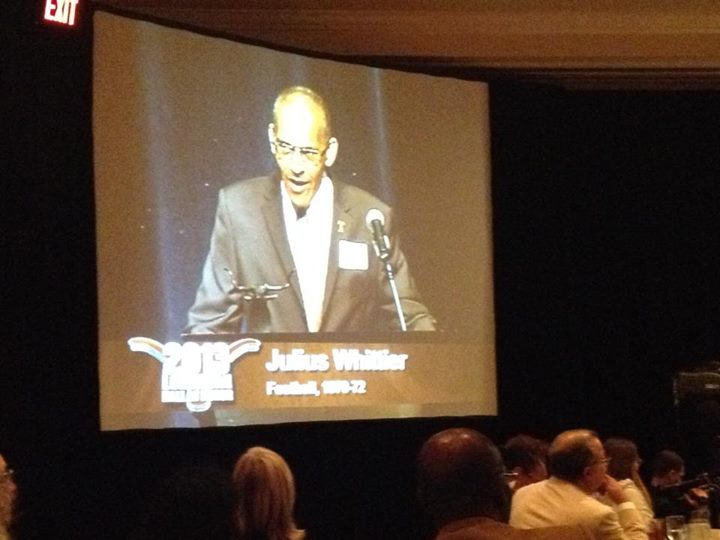

Julius Whittier Entered the Hall of Honor in 2013

Julius Whittier’s contributions to Longhorn heritage represent a portal to the past that reminds Longhorn fans that sports history shapes the present and empowers the future.

One Comment