Bill Little Articles Part XIV

Bill Little articles For https://texassports.com–

-

A Toast to Willie Morris

-

A Birthday & Mexican Dinner

-

Heading to Lubbock

-

The Last of Legends

-

The Last Brick

-

Santa ???? is Coming

-

Harley Sewell dies at 80

-

In Their Time

-

The Best of Friends

-

A Turn in the Road

-

The Warrior Way

-

The Thread

09.13.2012 | Football

Bill Little commentary: A toast to Willie Morris

Sept. 13, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

OXFORD, MS – No one – absolutely no one – would have loved this Texas-Ole Miss football game at Vaught-Hemingway Stadium more than Willie Morris. He loved sports, he loved Texas and Austin, and he loved Ole Miss and Oxford.

In this college town in Mississippi, Willie Morris was a literary giant in a haven of great writers. Modern day John Grisham still visits here regularly. The late William Faulkner’s home, Rowan Oak, is a local shrine. Square Books has hosted signings by such famous authors as Stephen King and John Grisham – at the same time.

But it is Morris, who died in 1999 down the road in Jackson, who would have been a likely choice to flip the opening coin toss at Saturday night’s game. After growing up in Yazoo City, Miss., he came to The University of Texas at Austin in the mid-1950s. He was elected editor of the Daily Texan, and his scathing editorials against segregation, censorship and government corruption won him no prizes with the UT administration. He was named a Rhodes Scholar, and after graduation from the other Oxford – the one in England – he eventually returned to Austin as the editor of the liberal weekly newspaper The Texas Observer.

He migrated to New York City, where he served as the youngest editor ever of Harper’s Magazine, and then he wrote “North Toward Home,” which became one of his most famous books. In 1980, he became a writer in residence at Ole Miss, and lived his final years there. While writing was his vocation, sports were his avocation.

Langston Rogers, the long-time media relations director at Ole Miss, remembers Morris sitting in the lounge at the Holiday Inn in Oxford with his black Labrador retriever, Pete, by his side, regaling folks with stories – including those memorialized in his books about trips with his father to football games and the puppy dog he immortalized in his book (which later became a movie), “My Dog Skip.”

Morris’ relationship with Oxford (the one in Mississippi) extended to reverence when talking of things such as the pre-game parties at The Grove – the tailgating capital of the South – near the football stadium. He also was known for taking guests on a late-night trip to the local cemetery to visit Faulkner’s grave. There, with a bottle of spirits of choice, he would announce that, “Mr. Bill is thirsty.” And then he would pour out the contents and leave the empty bottle on William Faulkner’s tombstone. It is one of those literarily inclined in Oxford to this day.

The irony of Morris and his odyssey is that he and Texas’ legendary football coach Darrell Royal were ships passing in the night at UT. Morris left after graduating in the spring of 1957, as Royal was preparing to coach his first season in 1957. However, as the years passed, Morris and Royal would become great friends. And the connection with Texas and Ole Miss would also have significant impact on Royal’s early career. Fact is, the meetings of the schools in bowl games following the 1957 and 1961 seasons arguably represent the lowest and highest points of Royal’s early career at Texas.

The season of 1957 was a Cinderella story for Royal, who had come to Texas following a 1-9 season for the Longhorns in their final year under favorite son Ed Price. In that opening season, Royal’s team surprised the country. They knocked off four nationally ranked teams, including a shocking 9-7 win at Texas A&M that knocked the Aggies out of national contention.

It was an era of excellence at Ole Miss, however. The Rebels of Johnny Vaught were a juggernaut of Southern football, and when Texas, at 6-3-1, was a surprise invite to the Sugar Bowl to meet the No. 7 ranked Rebs, Royal knew he was overmatched. And he was. The story goes that Royal was so embarrassed by the 39-7 thrashing that he walked out of a post-bowl team dinner and gave his watch to a guy on Bourbon Street. That, by the way, has never been verified.

What is true, however, is that four seasons later, Royal and his Longhorns would find redemption. This time, the game was a national showcase.

Ole Miss was still a major force in college football, and Texas had held the nation’s No. 1 ranking for much of the regular season until a stunning 6-0 loss to TCU in the next-to-last game of the year knocked the ‘Horns out of contention. In the final rankings (which were done before the bowl games back then) Texas had finished No. 3 and Ole Miss was No. 5 when the two headed into the Cotton Bowl Classic in Dallas on New Year’s Day, 1962.

Royal’s first bowl win at UT had been elusive. Texas followed that Sugar Bowl loss with a defeat to Syracuse in the Cotton Bowl game following the 1959 season, and a 3-3 tie with Alabama in the 1960 Bluebonnet Bowl. But riding the wings of perhaps the best offensive team of his career, Royal used a surprise 80-yard quick kick by all-American running back James Saxton to seal a 12-7 victory and claim his first bowl game win.

This 2012 version of the match-up has far different, and yet still important ramifications. It is the first road game for Mack Brown‘s very young football team. The times have changed since Willie Morris held court in that bar in what was then a sleepy college town. Folks who know say this game is one of the biggest things to happen in Oxford, where the Rebels are a dominating 40-6 against non-conference foes recently.

ESPN-TV will be airing the game nationally in a late (8:15 p.m. CDT) window, giving the country a look at the two schools who were national powerhouses fifty years ago.

The Longhorn coaches are anxious to see how the development progresses for a team that will close out the first quarter of its 12-game regular season with this road trip. As the non-conference schedule ends Saturday, Texas will follow its bye week next week with a trip to open Big 12 play at Oklahoma State on September 29.

Saturday’s game will be intriguing and watched with interest across the country. And maybe, if the moon is just right, Willie Morris (wherever he is) will cover the game and drink his own toast to the two schools which drew his allegiance so many years ago.

07.06.2012 | Football

Bill Little commentary: A Birthday and a Mexican dinner

July 6, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Of all the words in the English language, the word “unique” is rare. It is rare because it requires, nor will it accept, no surrounding superlatives. You can’t say “very unique,” “so unique” or even “extremely unique.” Unique is…well, unique.

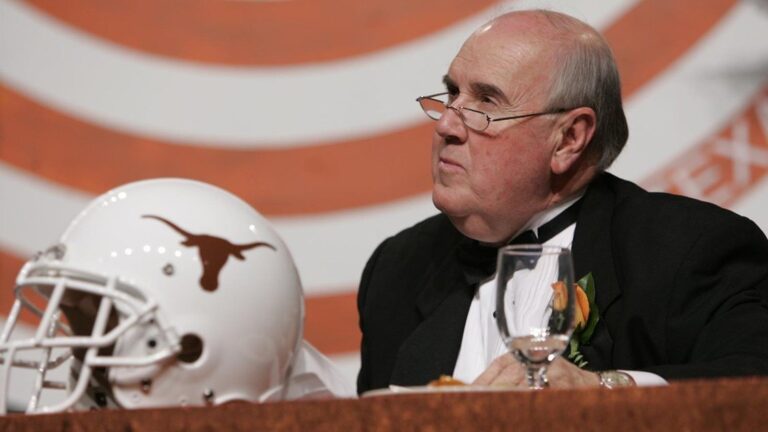

The subject came up a couple of times Friday as a group of about 50 former players gathered to celebrate the 88th birthday of their coach, Darrell Royal. With each moment, and each comment, Royal’s impact on their lives – and the lives of all those associated with The University of Texas football program – was a reminder of a meaning and a strength that transcends years.

The flowers on the counter in the party room of Matt’s El Rancho further emphasized the occasion, as the restaurant which has been so connected to Longhorn athletics for all these years prepared to celebrate its 60th birthday on Saturday.

Mack Brown had started the day for Darrell and Edith Royal with a good-wishes phone call from his house in the mountains of North Carolina. President Bill Powers was rushing from a meeting to try to arrive in time.

Players who spanned an era of Texas football from 1957 through 1976 each spoke briefly. Former Longhorn quarterback T Jones was there, thanking Royal for hiring him as a 26 year old assistant coach when he came to Texas in December of 1956. Fred Akers, who joined Royal’s staff as an assistant in 1966 and later returned as the Longhorns’ head coach himself, thanked Royal for plucking him from the ranks of high school coaches and “giving me a chance to become a college coach.”

With only a handful of exceptions, the men in the room had either played or coached for Royal during one of the most successful runs in the history of college football. But to many, he had been more than a coach.

“It may be your birthday,” said Jim Bob Moffett (who played on Royal’s first teams), “but to us, it is a little like Father’s Day. Because you have been like a father to a lot of us.”

As the sun bathed the courtyard of the restaurant beyond the latticed windows, the clock turned back. For Royal, it was a celebration of a variance of “family.” Many of these same men, including former basketball assistant coach Eddie Oran, see Royal on a regular basis. They follow a schedule, taking turns taking him to lunch. There’s a table at a restaurant near the facility where he and Edith live that’s held available daily for him to drop in for a meal or a cold beverage.

Friday’s gathering was also the anniversary of another Texas tradition, because it was 50 years ago, in the summer of 1962, when Royal and a local sporting goods salesman named Rooster Andrews introduced the modern football world to the uniform color of burnt orange.

Urban legend would eventually suggest that Royal, who was known for his affinity for running the football, created the color to deceive opponents because of the similar colors of the new home jerseys and the leather footballs.

Nothing, Royal said Friday, could be further from the truth.

Ronnie Landry, an offensive lineman in the 1960s who was a freshman in 1962, remembers a couple of varsity players modeling the jerseys. Pat Culpepper, who was a star senior linebacker, remembers nothing close to the stir caused by some of the new uniforms of today.

The truth is, Royal had tired of the orange color which Texas had been wearing since World War II. It was a darker version of the light orange worn by Tennessee, and no one manufacturer seemed to be able to match the color year after year.

That was what prompted Royal to ask Rooster to research the color, and when he did, he came to realize he was seeking something that had already been created.

In 1928, Texas coach Clyde Littlefield had sought a resolution of a problem with the school colors. The orange dye used at the time tended to fade when washed, thus reducing it almost to a lemon yellow color. Thus came the derogatory term “Yellow bellies” to describe the proud Longhorn players. Littlefield went to a friend in the garment business in Chicago, and together they created the burnt orange color and it was officially named “Texas Orange.”

That was the color Texas wore until the 1940s. It seems the dyes used for the dark orange color came from Germany, and during World War II that wasn’t available. So the lighter orange had to suffice, until Royal and Andrews stepped in.

“I was looking for something that would be only ours,” Royal said Friday. “Besides, it was our original color.”

When the Longhorns take the field in September to open the 2012 season, it will have been 50 years since the burnt orange color arrived on the college football landscape. The myth about the color of the football still surfaces from time to time, but there are some interesting figures in that regard. The Longhorns, of course, wear the orange jerseys at home, as well as in some bowl games and as the home team every odd year against Oklahoma in Dallas.

During the first three years Texas wore the new jerseys, from 1962 through 1964, Texas was 15-2 (with a win over Roger Staubach and Navy in the Cotton Bowl) while wearing orange, and 15-0-1 (with a win over Joe Namath and Alabama in the Orange Bowl) while wearing white.

In the ten years between 1962 and 1971, the Longhorns were 49-12-1 in orange and 39-6-1 in white, and Royal was named coach of the decade by ABC-TV. So much for the theory of deceptive trade practices.

As Royal posed for pictures with legendary players such as James Street and Bill Bradley and the noon luncheon began to drift into the remains of the work day on a hot July 6 afternoon, Royal thought of one more thing about the jerseys that pretty well summed up them, and him.

“I wanted,” he said, “for it to be unique.”

And that, without superlatives, is Darrell Royal at 88.

01.12.2012 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The last of the legends

Jan. 12, 2012

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Chances are, you have no reason to know about Canute the Great, a Viking who became king of England, Denmark, Norway and parts of Sweden. But it was Canute who once proved the infallibility of man by walking to the sea and commanding the waves to stop.

When they didn’t, he uttered the now-famous, loosely translated, phrase, “Time and tide wait for no man.”

We are sadly reminded of that as we learn of the passing Saturday of Julian Garrett, thus closing a treasured moment in time in Texas Longhorn football history. Garrett, who had turned 94 three days earlier, was the last surviving member of a group of Longhorn football players featured on the cover of Life Magazine during the season of 1941, arguably the greatest team in the first half-century of Texas football.

To understand the significance of the magazine cover of November 17, 1941, it is important to understand the times. There were no sports magazines at the time. The Sporting News, was a newspaper published in St. Louis which covered major league baseball, but that was the only thing even close. Life Magazine was an icon, a weekly news features publication that was a pioneer in photojournalism. Exactly one year before, the issue of December 18, 1940, featured President Franklin Roosevelt on the cover. Two weeks before, actors Clark Gable and Lana Turner had shared the front page. And in a touch of irony – since the magazine had gone to press the week before – Gen. Douglas MacArthur was featured on December 8, 1941.

But in the days before all of their lives would change with the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the innocence of the age included a multi-page spread on the hottest team in college football, the Texas Longhorns. For a dime, on November 17, you could have been one of 13.5 million people who bought the most popular periodical in America and been introduced to 14 Longhorns on the cover, and candid photos inside with players and their families, and their coach, D. X. Bible.

The cover photos were of the eleven starters and three key reserves who were the regulars during an era where players played both offense and defense. Julian Garrett, a starting tackle, was one of a class of 125 recruits which Bible had brought into Texas as freshmen in 1938. The names of others would become like a roll call of the legends of the game at Texas. Malcolm Kutner, an end, would become UT’s first all-American of the modern era. Jack Crain, Pete Layden and Noble Doss the offensive heroes, along with Kutner. Wally Scott, one of the few juniors on the cover, went on to become a successful Austin attorney and one of UT’s most ardent supporters during the next sixty years.

Scott, Spec Sanders (a junior college transfer at running back who would go on to a fine pro football career), and R. L. Harkins were the non-starters among the fourteen. The others included end Preston Flanagan, tackles Garrett and Bo Cohenour, guards Chal Daniel and Buddy Jungmichel, center Henry Harkins, and quarterback Vernon Martin.

After a mid-season victory over SMU, the Longhorns were elevated to the nation’s No. 1 team, and appeared destined to play in the Rose Bowl – which would have been the first bowl game in school history. Part of that dream was dashed the next week, when the injury-riddled `Horns were tied by Baylor, 7-7. That was the weekend before the Life issue appeared on America’s newsstands.

Still, the hope of playing in the Rose Bowl remained, even after a subsequent 14-7 loss to TCU the following week. As the days dwindled down in November, Texas still had a final game on the schedule. After shutting out Texas A&M, 23-0, on Thanksgiving, the Longhorns had to wait until the first week in December to finish the ten-game schedule.

The Rose Bowl was still an option, but fate intervened. The Longhorns’ final game was against Oregon, and Oregon State had defeated the Ducks, 12-7. The bowl committee was concerned that it could be embarrassed if Oregon defeated Texas and the Horns headed to Pasadena off of a defeat to a team Oregon State had already beaten.

Intertwined in all of this was Bible, the legendary Texas coach. He was arguably the most visible figure in college football. He had won at Texas A&M and Nebraska before Texas made him their head coach and athletics director and paid him more money than the school president was making (which was really unusual at the time). Bible’s winning ability was well known, but his greater strengths were his character and his integrity. So when the Rose Bowl folks suggested that Bible cancel the Oregon game to clear the path for a Rose Bowl invitation, Bible staunchly refused on the principle that he had given his word to play, and UT, therefore, was going to play.

The Rose Bowl invited Duke, and by the time dusk came on the Ducks in Austin in the final game of the season, Texas had won, 71-7. It was December 6, 1941.

The next day, of course, the country was at war, and the lives of all of the players, coaches, and everyone had changed forever. The trip to Pasadena didn’t happen for anybody, as fears of a Japanese invasion of the West Coast of the U.S. caused the Rose Bowl to be moved to Duke’s home field in Durham, NC.

Many of the Texas seniors entered the Armed Forces, and some played with service teams during the war. A number tried post-war pro ball in spite of the rust they had collected. Sanders and Kutner were the most successful, although Doss was a member of Philadelphia’s NFL championship team in the late 1940s. Sanders returned from the Navy in 1946 to play for the New York Yankees in the old All-American Conference, and led the team to Division championships in 1946 and 1947. His 1,432 yards rushing in 1947 set the pro record which stood until 1958. In 1950, the team had been absorbed by the NFL, and Sanders led the league in interceptions with 13.

Kutner, who would become the only member of the team to make the National Football Foundation’s Hall of Fame (he was the only all-American, therefore the only eligible player), played five years with the Chicago Cardinals and was twice named all-NFL. He followed his playing career with great success in the oil business in Texas.

Upon returning from World War II, success in their lives after college would be a common theme for the players. Doss entered the insurance business and became one of Austin’s leading citizens. Crain was a member of the Texas House of Representatives. Layden, who as a baseball and football star is still considered one of the greatest athletes in Texas school history, went on to become one of the few players in history to play major league baseball and NFL football.

When Doss died in February of 2009, Garrett became the lone survivor of the boys who are forever young on that cover of Life Magazine. Garrett had spurned offers to play professional football after the war, and spent his time in the ship building industry during WWII. His life’s work would include many years in the petroleum industry in the Golden Triangle area of southeast Texas. His family, and his love for The University of Texas, punctuated a life well-lived.

Seventy years after they carved their legacy, most of the members of that 1941 team are gone. It is hard to put into perspective what they did for the school. Seventy years is a long time. What we do know is that they came from a time where their parents had survived “The Great War” (World War I), and the Great Depression. Their time at Texas was brief, in the grand scheme of things. And yet somehow, they rode into a mosaic that included men who would be later termed “The Greatest Generation.”

The character of Mr. Bible cast a long shadow on The University, which was, in its own way, trying to define its identity. The game, the school, the town, the state – all were different then. But the value of a university will always be represented by the people it produces…not as much for what they did, but for who they were.

And there, on the cover of Life Magazine, young men with hopes and dreams stare back at us. The realization of their accomplishments is great. But the promise they leave us is a reminder that universities aren’t about buildings, and teams are not just about wins and losses. In those photos, the fourteen young men look to a future – a future they had no way of realizing, or imagining. That is the gift they gave us, because that’s the gift that never changes. And as they march forever into the distance, it is that which we celebrate, respect, and honor. Because they remind us that generation after generation, college football is a game played by young people, whose present is undefined, and whose future is limitless.

12.29.2011 | Football

Bill little commentary: The last brick

Dec. 29, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

SAN DIEGO, CALIF. — In the end, the 2011 Bridgepoint Education Holiday Bowl belonged to those who have been there all along, and one who almost never was.

Wednesday night’s 21-10 victory over California closed the Longhorns’ reconstruction year at 8-5 — hardly what they had dreamed of earlier in the year, but a solid victory all the same. It is a redeeming quality of the collegiate football bowl season — about three dozen games produce darned near 20 winners. Arguments will continue among the fans and the media for years about reasons for an NCAA playoff system at the sport’s highest level, but in that scenario, one team is happy and everybody else is not.

This one came for Texas because a senior class never quit believing, their teammates (particularly on defense) rose to the occasion, and because Marquise Goodwin changed his mind and decided to play football in 2011 after all, rather than redshirt so he could continue preparations as a long jumper for the U.S. 2012 Olympic Team.

Goodwin, who joined the team for his junior season after the Longhorns had played their first game, made a similar impact offensively in the Holiday Bowl with a stellar second half. With the Longhorns trailing, 10-7 after Cal had taken the lead with an opening third quarter drive, Goodwin found separation behind a Cal defender and hauled in a 47-yard catch-and-run (and he does that second part very fast) pass from quarterback David Ash for a touchdown that gave the Longhorns a 14-10 lead.

Then, as the third quarter was ending, he turned what looked like a Cal defensive stop into a 37-yard run on a reverse that put the ball at the Bear seven and resulted in the game clinching touchdown on a four-yard run by Cody Johnson two plays later.

Of the Longhorns 163 total yards in the second half, Goodwin accounted for 89 all-purpose yards. Among the other standout moments for the offense, senior tight end Blaine Irby hauled in a 30-yard pass to set up the Longhorns’ first touchdown, and wide receiver Jaxon Shipley made it a perfect four-for-four in pass attempts with three touchdown passes, as he netted a TD on a four-yard pass to Ash for the Longhorns’ first score. Those three TD passes put Shipley tied for second for most TD passes by a true freshman (Ted Constanzo, 1975). Ironically, Ash’s touchdown pass was his fourth of the season which is the new record for touchdown passes by a Longhorn true freshman.

In a game that set a Holiday Bowl record for number of punts, Texas senior all-purpose kicker Justin Tucker set a bowl record with a 64-yard punt, and three of his nine punts were inside the Cal 20.

But for this Texas team, in the beginning of the season it was the defense that shined, and it would be the defense that would dominate with its best game at the end. It was hard to pick a star on a defense that limited its opponent to only seven yards rushing, recorded six sacks and had 13 tackles for a loss and forced five turnovers.

Senior linebackers Emmanuel Acho and Keenan Robinson led with eight total tackles, but the most impressive statistic on the chart was the fact that Texas was so solid individually, recording 42 solo tackles on the Golden Bears’ 69 total plays. Defensive end Jackson Jeffcoat had two sacks and two-and-a-half tackles for a loss and linebacker Jordan Hicks had one and a half sacks and two and a half tackles behind the line. The highlight defensive play of the game came from Kenny Vaccaro, who leaped over a Cal blocker to record a sack and also had two other tackles for a loss. Freshman cornerback Quandre Diggs, with his NFL brother and former Longhorn Quentin Jammer watching, had an interception and the Longhorns were credited with three forced fumbles and four fumble recoveries.

For the game, California netted only 195 total yards — 109 of which came on their first drive of the game (40 to their field goal) and their first drive of the second half (69 to their touchdown).

Throughout the week of preparation, Mack Brown had stressed that it was important to get a victory for the seniors, and when it was over, it was to the seniors he gave the credit. It was a senior class which had lost only one game in the final second to Texas Tech in 2008 and to Alabama in the National Championship game when Colt McCoy was injured in 2009. They, more than any group, had determined to move past last year’s 5-7 season, and this was their moment.

The victory also helped put the season into perspective. This was a team that took its “brick by brick” theme into a rebuilding process. By mid-season, until it was devastated by injuries to running backs Fozzy Whittaker (the heart and soul of the offense), as well as freshmen Malcolm Brown and Joe Bergeron, this team had become an impressive power running attack that appeared destined to finish among the nation’s elite. But without those players, and with the loss for more than a month of the standout freshman Shipley, Texas slipped at the end.

While the final record of 8-5 is not the usual standard of the Mack Brown era, it will be remembered for team and individual bright shining moments that will forever be remembered in Longhorn history. The bowl win ran Mack Brown‘s bowl record to 9-4, with a mark of 8-2 in the Horns last ten bowl games, including six wins in the last seven games. That only loss came in the BCS National Championship game in 2009.

The high point of the season, of course, was the dramatic victory over Texas A&M in the final game of the storied rivalry, when Case McCoy scrambled for 25 yards and Tucker kicked the game winner as time expired. Of all of the season’s plays, those will forever be etched in Longhorn lore with the names of men like Noble Doss, Bobby Layne, James Street, Roosevelt Leaks, Earl Campbell, Major Applewhite, Colt McCoy, Ricky Williams and Vince Young.

When defensive coordinator Manny Diaz talked about “the bridge” that would symbolize the game, he wrote the story before it ever happened. The seniors leave with a win, and time will remember them as those who righted a ship that seemed in stormy seas.

For the many who return, and the young coaches who will have their first full spring to begin preparations for 2012, it is the pathway to a new set of bricks. Joined with outstanding incoming freshmen, it will be they who attempt to continue the construction job. Manny Diaz will have some rebuilding to do with the loss of seniors Acho, Robinson, Kheeston Randall and Blake Gideon, and Bryan Harsin will have a full spring to work with quarterbacks Ash and McCoy. Stacy Searels will get his first full spring with the offensive line, along with hopeful newcomers who will be joining the team in January to begin their college careers.

As for Marquise Goodwin, the 2011 Longhorns will be forever grateful that he decided to forego his training for the Olympics to join his Texas football family for what turned out to be a memorable end of his junior year. This spring, he will split time between work with the Longhorn track team, working with Bennie Wylie in the weight room and checking in with Darrell Wyatt and his spring drills. He has, quite obviously, proved he can handle that schedule.

Attitude, they say, is everything in sports. And nothing helps attitude more than a victory. It is the stuff of which dreams are made, and the Longhorns have put themselves in position to dream positively, about bricks and bridges, and where they go from here.

12.25.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Santa Claus is coming

Dec. 25, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

SAN DIEGO, CALIF. — The prime question, for the children of the Horns, was whether Santa Claus could really find them at the shiny Marriott Marquis on Christmas Eve in this city by the sea. So just to cover his bases, the jolly old elf came early before the Texas team and staff left on Friday to begin preparations for their upcoming Bridgepoint Education Holiday Bowl on December 28.

The visions of sugar plums dance in the heads of a good portion of the Texas travel party, a reflection of the youth of the staff Mack Brown has assembled to lead the Longhorn football program. Young coaches have young kids. The infusion of excitement about Christmas is infectious for the Longhorn players, many of who are spending their first Christmas away from home.

San Diego obliged its visitors with a stunning chamber of commerce day, and the Longhorns spent a morning workout preparing for the game and then were guests at Sea World San Diego in the afternoon. It was a great orientation following Friday’s travel day.

Sunday the team will observe Christmas Day with a voluntary chapel service and evening dinner, which will follow a morning practice and a trip to the world famous San Diego Zoo.

In a press briefing prior to the Saturday morning practice, Mack Brown discussed the team’s need to finish strong in their game with California. In retrospect, he said, the Longhorns lingered too long in the glory of their Thanksgiving night victory over Texas A&M and failed to respond the next weekend when they played Baylor on December 3.

The Holiday Bowl offers an opportunity to rebound and a victory would take the Longhorns’ final record to 8-5.

Texas is playing in its fifth Holiday Bowl, and there is a lot of positive history entwined between the Longhorns and this game. Each time Texas has played in the game, win or lose, it has provided a launching pad for something special. In 2000, Texas missed on what would been a game-winning touchdown in the closing minutes in a loss to Oregon. The next season, the Longhorns advanced to the Big 12 Championship game and came up two points shy — in a 39-37 loss to Colorado — from playing for the national championship.

A return trip to San Diego that season earned Major Applewhite Holiday Bowl Hall of Fame honors and launched the career of a freshman linebacker named Derrick Johnson in what was then the Horns biggest come-from-behind victory (19 points) in school history to beat Washington.

But it would be the next two games here that would best characterize Texas in the first decade of the 21st century. In 2003, Texas lost by eight points to Washington State. The next two years produced two BCS trips to the Rose Bowl, including victories at the end of the 2004 season over Michigan and over USC in the BCS National Championship game for the 2005 season. Texas capped an up-and-down 2007 with a win over Arizona State here, and then finished third and second in the national rankings in 2008 and 2009.

The Horns enter this trip hopeful and healing — the former directly related to the latter. Injuries to freshmen runners Malcolm Brown and Joe Bergeron and receiver Jaxon Shipley and the loss of veteran tailback Fozzy Whittaker hammered an emerging Texas offense at midseason. Though Whittaker is gone for the year, the other three are expected to be healthy.

As he greeted his team on Friday and again at practice on Saturday, Brown stressed the fundamentals which dictate outcomes in all games, but are particularly important in bowl games.

“A bowl game is like starting a season,” Brown said. “The kicking game will be key, as will turnovers.”

Those are the basics, it is true. But reflecting on bowl games played and those about to be played, the victor almost always is determined by the team which arrives ready on game day. This game, more than any other, will be decided by attitude.

That is why a week’s preparation for a bowl, particularly around Christmas Day, is really significant. Practice Monday (which is like a Thursday practice on a normal game week of preparation) will be followed by perhaps the most significant event annually at the Holiday Bowl – the Navy and Marine Corps Luncheon aboard an aircraft carrier. There, the Longhorns will sit down with Cal players and hundreds of sailors and Marines who are on active duty. There, 18- and 19-year-olds will break bread together. It is a stirring reminder that agenda and purpose vary, and it is a chance for the players to show respect for those who stand in harm’s way on their behalf.

As the sun slowly set on the Pacific across the bay from the Marriott on Saturday, the little kids began dreaming of Santa, and the players reflected on the coming days. For the staff and coaches, it was a time of remembering, and a time of thanksgiving. Christmas means different things to different folks, and that is how it should be.

For some, it is a remembrance of a time long past; a moment when believing was stronger than reality, and hope overshadowed despair. The distant glisten of the sea reminds us of that. It is a beacon shining, a reflection of memories and a validation of miracles.

That is why this bowl trip for this Texas team is so important. Life, after all, is a connection of souls to a Higher Being, and a thread that binds us together and a family as children of the universe. Somewhere between Santa finding San Diego, and the story of a star and a baby, we are reminded that we may be alone, but we don’t have to be lonely.

There is, we are told, the matter of angels. Movies are made about them, books and songs tell their story, and like the kid who can’t figure Santa, we wonder if they are real. Paul Crume, the late columnist of The Dallas Morning News, wrote a column in 1975 that addresses that, and on this Christmas, I will leave you with it because it tells it better than I could:

“A man wrote me not long ago and asked me what I thought of the theory of angels. I immediately told him that I am highly in favor of angels. As a matter of fact, I am scared to death of them.

Any adult human being with half sense, and some with more, knows that there are angels.

If he has ever spent any period in loneliness, when the senses are forced in upon themselves, he has felt the wind from their beating wings and been overwhelmed with the sudden realization of the endless and gigantic dark that exists outside the little candle flame of human knowledge. He has prayed, not in the sense that he asked for something, but that he yielded himself.

Angels live daily at our very elbows, and so do demons, and most men at one time or another in their lives have yielded themselves to both and have lived to rejoice and rue their impulses.

But the man who has once felt the beat of an angel’s wing finds it easy to rejoice at the universe and at his fellow man. It does not happen to any man often, and too many of us dismiss it when it happens.

I remember a time in my final days in college when the chinaberry trees were abloom and the air was sweet with spring blossoms and I stood still on the street, suddenly struck with the feeling of something that was an enormous promise and yet was no tangible promise at all.

And there was another night in a small boat when the moon was full and the distant headlands were dark but beautiful and we were lonely. The pull of a nameless emotion was so strong that it filled the atmosphere. The small boy within me cried.

Psychiatrists will say that the angel in all this was really within me, not outside, but it makes no difference. There are angels inside us and angels outside and the one inside is usually the quickest choked.

Francis Thompson said it better. He was a late 19th-century English poet who would put the current crop of hippies to shame. He was on pot all his life. His pad was always mean and was sometimes a park bench. He was a mental case and tubercular besides. He carried a fishing creel into which he dropped the poetry that was later to become immortal.

‘The angels keep their ancient places,’ wrote Francis Thompson in protest. ‘Turn but a stone, and start a wing.’

He was lonely enough to be the constant associate of angels.

There is an angel close to you this day.

Merry Christmas, and I wish you well.“

12.19.2011 | Football

Harley Sewell dies at 80

Dec. 19, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

The death this weekend of former Longhorn great Harley Sewell, 80, brings to mind the story of the recruiting of one of Texas’ all-time greatest football players. In the days before the sophisticated systems of recruiting that benefit today’s football programs, great players were often discovered in out of the way places. But no one more so than Harley Sewell, who became one of the greatest linemen in college and pro football history.

The scene is somewhere in far north central Texas, on a hot summer day in the 1940s not too long after World War II. Phil Bolin, who had played at Texas and was a Longhorn fan, was bird-dogging talent for the UT coaching staff. He had heard of a player in the little town of St. Jo – population 900. And he was driving the county roads trying to locate him. He discovered him atop a telephone pole, working at a summer job as a lineman.

“Son,” Bolin hollered up the pole to the big blond youngster, “How would you like to play football for the University of Texas?”

“Be fine,” Harley Sewell called down the pole.

A few days later, coach Blair Cherry sent him a penny post card, and Sewell signed with Texas.

He arrived at Texas with just a pair of faded blue jeans, a couple of tee shirts and one slightly scuffed pair of work boots. A month into his stay, however, he was homesick. He was packing his old cardboard suitcase when then assistant coach J. T. King came into his room. Sewell would toss a pair of socks into the suitcase, and King would toss them out as he worked on convincing him to stay. In the end, it worked.

And Texas football, and the game of football in general, would be the better for it. Sewell would go on to become one of the greatest linemen ever at Texas. He was a two-time All Southwest Conference selection who earned All-America honors as a lineman in 1952, when he helped Texas to a 9-2 record and a victory over Tennessee in the 1953 Cotton Bowl, where he earned MVP honors. In that game, he led a UT defense that limited the Vols to six first downs and minus 14 yards rushing.

He was the first Longhorn to play in the post season all-star game, the Hula Bowl, and he was a first round selection (13th overall pick) by the Detroit Lions in the NFL draft.

Harley played for the Lions from 1953-62 before finishing his 11-year career with the L.A. Rams. A four-time pro bowl selection, Harley would forever be linked with fellow Texans Bobby Layne and Doak Walker at Detroit, where they earned NFL championship rings in 1953 and 1957. For over 30 years following his retirement from the field, he still worked in pro football, as a talent scout for the Rams. In that role, he became one of the most respected – and loved – men in the NFL scouting business.

Harley was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2000, and several years ago they dedicated the football field in Saint Jo in his honor.

The story of Harley’s odyssey from Saint Jo to Texas had one more twist. As the late J. T. King used to tell it, Harley was playing in the Oil Bowl in Wichita Falls the summer before he came to Texas. He was told to stop by a hotel for a meeting to discuss coming to Texas. Harley knocked on the door, and when King answered he said, “Are you the coach for the University of Texas?”

“I’m one of them,” King replied.

And in disbelief Harley replied, “One of ’em? How many y’all got?”

What we’ve learned over the years is that Texas did have a lot of coaches, and a lot of great players. But when it was all said and done, there was only one Harley.

Visitation is scheduled Tuesday, 5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. at the Arlington Funeral Home in Arlington. Funeral services will be at 2:00 p.m. Wednesday at the Arlington Funeral Home chapel, with interment following at the Mount Olivet Cemetery. Donations may be made to the Alzheimer’s Association.

11.26.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: In their time

Nov. 26, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

COLLEGE STATION – Everyone thought that final Texas-Texas A&M football game on Thanksgiving Night would be about memories.

Instead, it was about dreams.

Case McCoy was 14 years old the first time his brother, Colt, came to Kyle Field in College Station as a member of the 2005 Longhorn team. He was just two years removed from seven years of grueling treatment for a rare auto-immune disease called scleroderma that had begun when he was five.

“I have dreamed of playing in this game for a long time,” he would say late Thursday night.

Justin Tucker used to go with his dad to Westlake High School when he was a kid, kick the football at the uprights on the football field, and imagine one final swing of his leg to win the game for Texas against Texas A&M.

And somewhere along the way, “make believe” and “play like” were transformed to a surreal reality on a night when the defense played incredibly well against a really good Texas A&M team, and dreams transcended hope, and wove their way into believing.

For much of the game, Manny Diaz‘ defense had fought tenaciously and successfully to protect their goal line against a Texas A&M offense that has been as good as any in the country this season. After the Aggies scored on their opening drive, the UT defense limited Texas A&M to four field goals. They intercepted three passes, including one which Carrington Byndom returned 58 yards for a touchdown early in the third quarter. Led by seniors Emmanuel Acho, Blake Gideon and Keenan Robinson, they recorded eight tackles for a loss. Until the final Texas A&M scoring drive of 68 yards, they had given up only 260 total yards and one touchdown for the game. In fact, in the final statistics, removing the first and last Aggie drives, the Longhorn defense allowed only 193 yards on 68 snaps of the ball.

Still, that valiant effort hung in the balance when Texas A&M scored with 1:48 remaining in the game to take the lead at 25-24. But Diaz and his crew had one arrow left to shoot, and they turned it loose on one of the three most important plays in the series’ final game. As the Aggies went for two, Texas went for the throat. Aggie quarterback Ryan Tannehill had barely gotten the snap when Acho and Keenan Robinson came untouched on a full gallop blitz. As Tannehill rolled right, running for his life, he spotted a receiver at the right edge of the end zone. But Kenny Vaccaro slowed the intended target’s progress, and Adrian Phillips stepped in front and knocked the ball away.

“At that moment,” Mack Brown would say later, “I knew we were going to win the game.”

It had been two years since the last of those clutch comebacks that had become a trademark of Texas. Memories of Vince Young’s run against Kansas, the two Rose Bowl wins, the victory in the Fiesta Bowl over Ohio State, and last second game winning field goals by Dusty Mangum, Ryan Bailey, and Hunter Lawrence seemed a distance away. Longhorn magic, it seemed, had been on vacation for awhile.

For most of the game, the Longhorns had been trapped deep in their own territory. Positive field position had been non-existent. Texas had managed only 189 yards on offense against those odds, and now, here they were, back at their own 29-yard line, with just 1:48 left in the game.

Dr. Ruben Pizarro, who does the Longhorns’ Spanish language broadcast, has given Longhorn players fun nicknames in Spanish during his years with the team, and at the UCLA game he came up with one for Case McCoy.

Harry Houdini was a famous escape artist in the 1930s, and that’s what Ruben thought of when he saw McCoy against the Bruins. He named him after Houdini and called him “El Mago” – the magician. Locked deep in their own territory for most of the game, it was time for the Longhorns to escape.

Nothing that had occurred to that point foresaw what would happen next. Mack Brown remembers telling McCoy, “It’s your time. God has given you another chance.”

Somehow, he had to get Texas to Justin Tucker.

It was first down, just inside Texas A&M territory when it happened. McCoy rolled left, then spun to an open middle of the field and began running.

“It was instinct,” he would say. In the stands, Brad and Debra McCoy watched as their youngest son, who had gone through so much as a child, began to run. Twenty-five yards down field, he was hit by one, then two, then another and another Aggie. Four finally surrounded him, trying desperately to pull the ball from the iron-lock grasp of his right arm. But little boys who dream don’t give up easily, and neither did Case McCoy. The kid’s never quit in his life, and he wasn’t about to then. When the play ended at the Texas A&M 23 yard line, twenty-eight seconds remained. Justin Tucker was in range.

Texas stopped the clock with three seconds showing, and Tucker, along with his kick team including deep snapper Alex Zumberge* and holder Cade McCrary, came onto the field. The jumbotron at the south end of the field loomed over a stadium now totally involved in emotion. Texas A&M called the obligatory timeout to freeze the kicker as he lined up for a 40-yard kick into a soft breeze, but it served no purpose. Justin Tucker was frozen in time, lost in his moment with his dad so long ago.

It was a perfect kick, it was a joyous celebration, and an historic series finished with an ending for the ages. Texas had won, 27-25. Big games do make interesting heroes, and history will place this one with the best. And when they remember, they will think of two little kids and their teammates who grew up to be big boy heroes, all part of one of the more valiant efforts ever by a Texas team. Never, in the 118 years of the rivalry, had it been decided on the game’s final play.

In the locker room after the game, as the celebration had wound down and the interviews were over, Case McCoy sat unwinding the wrappings that had covered his body. His field and sweat stained No. 6 jersey lay nearby. But his mind was no longer on the events in the once-maroon filled cavern outside.

“We’ve got Baylor next week,” he said. “That’s all I am thinking about right now.”

In a way, it was the fitting comment to close the chapter. College football is what it is because of the memories – those tucked carefully with the millions of fans who are given the gift to remember. History is huge there. But most of all, college football is about those who play it, the young men who come of age in a myriad of circumstances. It is they who dream, and they who do. They may be pieces of adults who both thrill and frustrate us, but it really is their world – their moment, and their time.

11.24.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The best of friends

Nov. 24, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

COLLEGE STATION – Remember when you were a kid, and your best friend’s dad got transferred to another town? You vowed to remain close…said nothing would be different. Pals forever. But the miles, and the years changed everything. And you found that emotion gives way to reality, and in time, the old relationships were never the same.

That is the destiny of the Texas-Texas A&M rivalry in football. With the moving of the Aggies to the Southeastern Conference, the game as we have known it will be gone forever. Even if the two schools do, one day, agree to play again, it is folly to think it will be anywhere close to the same. Actions, we are taught, have consequences, and the result will be manifested on Thanksgiving night.

For 118 years, it had been played, with the teams in the same league for most of the last century.

It had begun in 1894, this football series between The University of Texas and what was then Texas A&M College. In the years that would follow, it would become one of the great rivalries in College Football. And Thursday night, it all ends.

All of us who have been around the series for a while, or for just a stop, have vivid memories. I was 17 years old when my brother Harvey and I drove from Winters, just south of Abilene, to College Station to watch the Longhorns and the Aggies play. Darrell Royal was in his third year at UT, and the ‘Horns needed a victory to claim Royal’s first Southwest Conference title, and first Cotton Bowl trp. They got it, but not before quarterback Bobby Lackey led them from a 10-0 halftime deficit with two fourth down conversions in the fourth quarter.

Four years later, in the shadow of one of the nation’s darkest hours, the Longhorns again needed a come-from-behind win to garner their first National Championship. In 1965, the Aggies stunned the folks from Austin with a trick play called “the Texas Special” (a bounced lateral that turned into a touchdown pass.) That brought a 17-0 Texas A&M halftime lead, and it led to one of the storied moments of Royal. His only speech to the team at intermission was to write the “17” on the board, and converted it to “21-17.” And with three touchdowns in the second half, Texas won, 21-17.

In 1969, the Longhorns Wishbone offense was so dominating statisticians wondered what the record was for a team going an entire game without ever facing third down. Earl Campbell clinched his Heisman in a rout in 1977. Starting in 1985, Texas A&M won five straight games in College Station, and the Aggies’ “Wreckin’ Crew” defense became dominant.

When I was working on a book called “What It Means To Be A Longhorn,” I asked Ricky Williams of his memories of “The A&M game.” I assumed, of course, that he would talk about his record setting performance in Austin in 1998. But Ricky, as was his nature, turned instead to a team victory. He remembered the season of 1995, when Texas had taken down the great Aggie defense to win the final Southwest Conference Championship. Since that game, the Longhorns have dominated the series, 11-5, including games in both Austin and College Station. Mack Brown‘s teams are 4-2 at Kyle Field, once considered one of the toughest places to play in America.

One by one, the memories return, each with a special twist, depending on the color you prefer, or the school that you have come to love. And love and family has been what this thing has always been about. It has been like brothers who squabble, but share a common bond. It is a game where legends played, and legends were made.

They are all gone now, with their tattered pennants and their faded uniforms. It would be wrong to call it the passing of an era, because it is much more than that. As Texas A&M moves to uncharted waters in the Southeastern Conference and Texas remains a pillar in the Big 12, the landscape of the college game, and the Lone Star state, changes forever.

And so, to pick a greatest moment – to pick a single legend – becomes impossible. In a way, it is rather like the putting away of Christmas decorations that have adorned the family tree for generations. Place them gently in a box, tuck them away, and treasure their memories.

For well more than a century, this series has brought people of the state together, in a friendly (though sometimes heated) rivalry. Blended families, particularly from the days when Texas A&M was an all-male institution and most of the pretty girls went to Texas, have long been part of the fiber of the state of Texas. It has been unique, in that people who were business partners and husbands and wives would share the same Thanksgiving dinner, but cheer fervently for their respective team. And when the game was over, on the next day they would go back to work, side by side, building lives together.

It was, in its own way, the rarest of competitions. In a 27-game span from 1940 through 1966, Texas won 24 games. There were two Aggie victories and one tie. That would have been enough to dull some rivalries, but not Texas and Texas A&M. The roots were deep, and firmly planted in the history of the state’s two flagship institutions.

For the Longhorns, it has been a series of heroes and memorable moments. Who will ever forget Noble Doss’s famous catch that beat the Aggies, 7-0, in 1940? It was an upset of epic proportions, coming as the Aggies were ranked No. 1 and seeking to duplicate their only National Championship in football, which was won in 1939. The Red Candles – the genesis of Texas Hex rally of later years, came out when the Longhorns won for the first time at Kyle Field in 1941. Duke Carlisle and the Longhorns’ 1963 team won UT’s first National Championship, coming from behind in College Station in an historic time less than a week after President Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas.

Texas rolled in the Wishbone years, and the Aggies had a successful run in the 1980s. In the twilight of the old Southwest Conference, Ricky Williams played brilliantly and James Brown played bravely in winning the league’s final game in 1995 in College Station. And then, of course, 1998 brought Ricky’s run to the NCAA record books in Austin. The recent years would bring Vince Young and Cedric Benson, Chris Simms and Colt McCoy. Twice – in 2005 and 2009 – the Longhorns beat the Aggies on the ‘Horns’ way to playing for a national championship.

Many will say that their greatest, most moving moment in this rivalry came in 1999, when 12 young people died when the Aggie bonfire fell shortly before the game. Mack Brown and his wife Sally had organized a blood drive, and Texas turned its Hex Rally into a memorial service shared by both schools.

In a moment of silence after the Longhorn band played the hymn “Amazing Grace” during its halftime performance, those who were there felt a kinship unlike any other, as the only sound was the tolling of a bell, and the rustling in the wind of the flags of the two schools.

The memories, and the stories, are legion, but perhaps it is there that we should stop. As this game winds down and the clock clicks zero, that is truly how we should remember. Because in that space, this has never been just about balls and scores and bragging rights and trophies and championships. It has been, after all, about people – a small, but very significant part of being Texan…a shining moment that is gone, but not forgotten.

11.13.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: A turn in the road

Nov. 13, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

COLUMBIA, MO – Saturday reminded me of something I wrote several years ago, reconnecting my college learning experience with the reality of the day.

Etched in my memory is a college English professor who was trying to get us to understand the poet Robert Frost. Frost, you will recall, wrote a poem entitled “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.”

In it, the writer is traveling on a cold winter night, and stops along the road to observe a scene. He ends the poem with words, “The woods are lovely, dark and deep, but I have promises to keep, and miles to go before I sleep…and miles to go before I sleep.”

When our professor asked us what the writer meant, at the time, being a cut-to-the-facts journalism major, I simply said the guy saw a significant scene and wrote about it.

Saturday in Columbia, I remembered that a few years ago the answer to the prof’s question came to me. What he meant was, whether the scene is beautiful or ominous, you can’t stop there. You have to go on. And so it is with the Texas Longhorns of 2011. Despite the loss to Missouri, and more significantly the loss of a player who represented a major part of the senior leadership of this team on the offensive side of the ball, there are still three games left in the season (plus a bowl game) that are on the schedule to be played. You can’t just pull the sled over and take a long November nap. Texas has two games to play in the next 12 days, and three within less than three weeks.

Mack Brown has often said what a fun team this has been to coach, and Saturday the fun took the turn of consternation. Officials at the University of Missouri say they will replace their dilapidated old artificial turf next year, but that will be too late for Fozzy Whittaker, whose right leg twisted without contact as he took a step on the seven-year-old field surface that has not weathered well the ravages of the Missouri winters. Fozzy was injured when he planted his foot to cut on the rock-hard surface.

The Longhorns had gone into the game short-handed at running back, but the recent involvement of Fozzy, both as an offensive force at running back and in the “wild” formation gave the Texas folks hope for a solid attack, despite injuries to Malcolm Brown (toe) and Joe Bergeron (hamstring) which hadn’t responded to treatment during the week. Both were tested before the game, and neither could safely play without threat of further injury.

But for this team of 2011, there has always been Fozzy. He was, unequivocally the heart and soul leader of a young offense which had only recently found its identity. And Fozzy was a huge part of that identity. And when he went down, despite whatever they tried, the Texas offense was unable to regroup. For this young team, it was a blow not unlike what the loss of Colt McCoy was to the 2009 team in the BCS National Championship game.

With the offense reeling, the Texas defense battled gallantly against Missouri, which would also lose their star running back Henry Josey late in the third quarter to a severe knee injury on the poor footing on the treacherous turf. Despite losing stellar senior linebacker Keenan Robinson to thumb injury on the game’s first series, the Longhorn defense held Missouri to only three points in the second half – and those came following a goal-line stand that came after a blocked punt gave the ball to the Tigers at the Longhorns’ one yard line. In the fourth quarter, Missouri gained only 55 yards.

The windy, gray day seemed a throwback to college football in the 1950s. There were – as there always are on days like this – some superb individual performances, and linebacker Emmanuel Acho turned in one for the Texas defense. Among his 14 tackles were five behind the line, as well as a stripped fumble that stopped the Tigers’ initial drive. The Longhorns had some good work from kicker-punter Justin Tucker and a punt block team which netted the Longhorns’ third safety of the season, but those, even with some outstanding defensive work, just weren’t enough to overcome the struggles of the star-stripped Texas offense.

In a way, the game was indicative of what has been a weird season throughout college football. The Big 12 has been a microcosm of the game nationally. Fraught with strange twists and inexplicable turns, 2011 has been a year where it is impossible to predict anything.

And that brings us back to the guy on the road looking at the woods. Texas is now 6-3 on the season, with three tough games remaining – two of which are on the road. Locked in the image of the scene they view is the loss of Whittaker, and the question marks of when several other playmakers may or may not return.

The youth, which has been the trademark of this team from the beginning, will now have to pull together under the leadership of a coaching staff which in its first season as a unit. Including a bowl game, they have four games remaining to write their legacy. Truth is, the road doesn’t stop in Columbia, Missouri, it only pauses. There, you gather your belongings and move past the woods.

You hurt for great guys such as Fozzy Whittaker, a young man who has already graduated and has done so much for so many people. He deserved a chance to finish his final college season differently. The hard thing, and the great thing about football is that it does mirror life. Hard moments give way to new opportunities, tough lessons begat positive learning experiences, and nobody ever promised this deal would be fair.

For the Longhorns of 2011, the 24-hour rule will be in effect. With two major games in the next 12 days, there isn’t time to feel sorry for yourself. You don’t forget the scenes of life – like the woods Frost told us about – but you do have to keep going. You still have miles to go.

11.06.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The warrior way

Nov. 6, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

The link between the U. S. military and the Texas Longhorn football program has been strong throughout the years of the Mack Brown era at UT, but perhaps never more evident than the events of Saturday in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium.

The paratroopers were perfect, the flyover impressive, the response from the crowd on Veterans Recognition Day was heart-warming. And in its own way, the Longhorn football team arrived ready for a battle.

In a team meeting Thursday, the members of the team were given camouflage tee-shirts to wear as they came into the stadium. Bennie Wylie, their football strength and conditioning coach, had talked that day about the mentality of the soldier. Wylie, whose twin best friends were Navy Seals, told them to forget what they had seen in the movies and on television about the military. And in that context, he took the “play to win” philosophy to a different level. Because he had worked at Texas Tech just two years ago, he also knew the opponent, and what it would take to win. He acknowledged that football is not war, but he made it clear that for those in the arena, it is a fight of its own kind.

It was Wylie who masterfully implemented the Longhorns’ theme of “brick by brick” to represent the rebuilding of a proud program, and it was to Wylie and honored World War II veteran Frank Denius that game balls were presented after the game. Denius, who chairs the Stadium’s Veterans Committee, has long been a fixture with the program. But it had been Wylie, during his grueling workouts in the off-season, who had the players run to the top of the west side upper deck. There, as they towered high above the field (and the campus for that matter), Wylie told them to envision themselves playing in the arena far below. It was, for them, “our house,” which was slowly being rebuilt – brick by brick.

Mack Brown has often said his program is built on “communication, trust, and respect.” And the respect aspect jumped to the front Saturday. First, there was respect – a respect that transcends into love – for Wylie and all that he has meant to them. Second, there was respect for their opponent, the Texas Tech Red Raiders.

Texas Tech had left its calling card of impressions in Norman, Oklahoma, where the Raiders had stunned No. 3 ranked OU. Despite a surprise loss to Iowa State, that is the team that showed up in Austin on Saturday. The Red Raiders opened on fire, with a 16-play drive that consumed over seven minutes of the first quarter. In a strange series that included 12 plays within the shadow of the Texas goal line, Tech had taken a 3-0 lead.

This day, however, would be a retro game for long-time Texas fans. Long known for defenses that “bend but don’t break,” that’s what Manny Diaz and his crowd were in the process of doing. On the flip side of the ball, the offense had taken its cue from a military operation. They had gone in “hot,” prepared, not to defeat, but to crush, their opponent.

It was 3-3 with 4:24 left in the first quarter. Over the next 20 minutes of the half, Texas would score 28 unanswered points to lead at intermission, 31-6. From a suite on the west side of the stadium, Darrell Royal smiled, and summoned the memory (on this Veterans Recognition Day) of his famous defensive guru and World War II pilot Mike Campbell. Texas Tech in the first half ran 45 offensive plays, including a glittering 23 of 31 passes for 219 yards. And had two field goals to show for it. Texas had rushed for 237 yards on 24 carries (that’s almost ten yards per play) and was dominating the game.

By the end of the third quarter, Texas Tech had 306 total yards and 13 points. Texas had 466 and 38. It was, plain and simple, exactly what the Longhorns had come to do. They were invested, not only in winning, but dominating.

The defense had done it by protecting their goal line and destroying Tech’s running game (the Raiders had 30 net yards on 27 carries), and the offense had rushed for 439 yards and amassed 595 total yards as the ‘Horns steamrolled to a 52-20 win. Texas never punted, and the only drives on which it failed to score were when they let the clock run out at the end of the first and second halves.

Not lost on the team in its locker room celebration was the fact that the victory was UT’s sixth of the season (against two losses), which made the ‘Horns bowl-eligible for the 13th time in Brown’s tenure at Texas. After missing out on a bowl trip last year, it was another brick in the wall of goals which had now been achieved.

The passing game was limited, but effective, despite the fact that leading receiver Jaxon Shipley missed the game with an injury – as did leading rusher Malcolm Brown. Freshman Joe Bergeron (191 yards) and veteran Fozzy Whitaker (83 yards) led the running game, and quarterbacks David Ash and Case McCoy were both impressive in guiding a turnover-free team through the 60 minutes of the game.

For Tech, the yardage numbers were impressive, but the results were not. Seth Doege was 40 of 55 for 381 yards, but the Raiders failed to score a touchdown until just a little over three minutes remained in the third quarter. The 52 points posted by Texas is made all the more impressive by the fact that all of the scoring drives were self-generated, without the aid of a turnover to help field position.

A key to playing Texas Tech well includes sure tackling, and Texas did not disappoint there. The defensive statistics from the game showed Emmanuel Acho with eleven tackles, nine each for Blake Gideon, Keenan Robinson and Kenny Vaccaro, seven apiece for Jackson Jeffcoat, Carrington Byndon and Kheeston Randall, and six for both Quandre Diggs and Alex Okafor. Doege was sacked four times, and there were 13 tackles behind the line of scrimmage.

With the victory over the Raiders behind them, Texas now faces the challenge of finishing their schedule with three road trips (to Missouri, Texas A&M and Baylor) in their final four games. The lone home appearance is November 19, when they host Kansas State.

But the second straight game with over 400 yards rushing clearly has established an identity for this Longhorn team of 2011. Power and strength, rewards from their work with Bennie Wylie over the summer and off-season work, characterize the rapidly improving team. Most important, it is clear they are not satisfied with what they have achieved. You do not build your house and forget to finish it.

So, it would seem, Bennie Wylie‘s trip with the players to the top of the stadium was significant in more than one way. It taught them to look down, to Joe Jamail Field far below, and envision playing before 100,000 people there, but it also taught them to look out in all directions. It is one thing to see where you are and where you have been. It is another to survey what lies beyond, and the possibilities of what’s out there to conquer.

11.04.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The thread

Nov. 4, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Every now and then, when you have a busy weekend of Texas football, it is interesting to realize that as big as something is, a common thread can usually be found. For Saturday’s events in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium surrounding the Longhorns’ game with Texas Tech, Mike Cotten is that thread.

When this 2011 team was practicing in August to prepare for the season, I remember watching the new excitement in the innovative offense and attacking defense and commenting to former coach Darrell Royal, “This team will remind you of your 1961 team.”

To which he replied, “Well, that’s a good start.”

Saturday, the 1961 Longhorn team will hold its 50th anniversary reunion. For those who saw it, and for those who coached it, many believe it was the best of all of Royal’s great teams. It was his first to achieve a No. 1 national ranking, and only a stunning 6-0 upset by TCU here in Austin kept it from being the first National Championship team in Texas football history. In an era where players played both offense and defense, it scored 303 points (despite the shutout) and allowed only 66. In fact, only one team – Texas Tech in a 42-14 loss – scored more than one touchdown against the UT defense.

In an era where points were usually hard to come by, it hammered most of its opponents. Its 12-7 win over a highly regarded Ole Miss team in the Cotton Bowl produced Royal’s first bowl win in his 20-year career.

Mike Cotten was the quarterback of that team.

Cotten had already had success against Texas Tech, throwing two 50-plus yard touchdown passes in 1960, when the Longhorns defeated the Raiders in Tech’s first-ever Southwest Conference game. The 42 points against the Raiders were the most UT scored against any opponent in that banner year of 1961.

That win, incidentally, really launched the Royal era in the 1960s. Using an innovative winged-T offense which employed a line alignment called the “flip-flop,” the offense not only baffled opponents, it captured the interest of the Texas fan base. It was a “score from anywhere” offense that was built on the concept of the strong running game to which Royal always adhered.

The difference, of course, in the 2011 team is that Royal’s 1961 team was filled with veterans. So where this young team is 5-2 and getting better, that one came into the year with a solid base of experience. What we saw last weekend, when the Longhorns rushed for 441 yards, is a calling card of the fundamental base Mack Brown and his staff are seeking. They want to be balanced between the run and the pass, but they want to establish the power running game that has been missing in the UT attack for the last several years. But there is no question that the intriguing possibilities for this Texas team is akin to the excitement felt for Texas football in 1961.

Cotten links the final piece of Saturday’s activities as well, and that is the observance of Veterans Recognition Day. When Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium was built in 1924 it was a monument to Texans who had served in what was known as “The Great War” – which is what World War I was known as at the time. The legend of the fall of Texas football had, for years, gone on to serve their country honorably in the years that would follow.

But by the time Mike Cotten and those players on the 1961 team were leaving college, the conflict in Vietnam had begun. With a commitment to military service on his life plan, Mike had entered a Marine Corps program during his freshman year at Texas. When he graduated, he entered UT Law School, and in 1965 he went on active duty as an officer. He rose to the rank of captain in Vietnam, and returned to a law practice in Austin at the end of his service stint.

Cotten remembers the excitement around the 1961 team, and likes what he sees from the 2011 Longhorns. The ball control game fits the memories of the Longhorns which Cotten captained, but the depth is also similar. In an era where there were no recruiting numbers limitations, Texas had three full teams which alternated – a similar philosophy to offensive coordinator’s reasoning for having packages which involved almost every player at some point in the game.

The 1961 team was the genesis of what would become the domination by Texas of the early 1960s. The sophomores (freshmen were not eligible then) on that team would finish their college careers with a National Championship in 1963, and would leave Texas with an amazing three-year record of 30-2-1.

When the Stadium Veterans Committee was formed in 1996, Cotten was one of the original members.

Saturday, he will gather with his former teammates at 9 a.m. in the “T” Room in the stadium, then hustle down to the field to be with the committee for pre-game ceremonies. That done, he will head to his seat to watch the modern era Longhorns.

For Cotten and his teammates, it seems hard to believe that it has been half a century since they carved their niche in the stadium. For the Longhorns of 2011, it is about seeking a sixth win, and continuing to rebuild their destiny, brick by brick.

But for the Wounded Warriors and other service personnel who are guests at the game, and for Mike Cotten and all of the Veterans Committee, this day is about memories far beyond the field. The meaning of the Memorial in the stadium stands sentinel for those who have fought and died so that freedom can live.

That is why, in tribute to them, the Longhorns will arrive at the stadium wearing camouflage T-shirts. In his years at Texas, Mack Brown has emphasized respect for the U.S. Military, and for the men and women who stand in harm’s way.

It will be a bright morning Saturday. Full of memories for some, and hopes for others. It is a thread that exists, not only for them, but for us all.