Bill Little Articles XVI

Bill Little articles For https://texassports.com–

-

Manny Diaz reinventing himself

-

Memorial Day

-

One Heckuva Man

-

The Cornerstone- A story of Bennie Wylie

-

Pipe dreams — Remembering Emory and the Wishbone

-

Arranging the Deck Chairs

-

The Short Happy Life of the Big 12

-

Remembering how to Win

-

The Presents of the Past

-

The Dozen

-

Understanding the Challenge

06.28.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Manny Diaz – Re-inventing Yourself

June 28, 2011

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of articles on the new coaches for the Texas Longhorns football team.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In the on-line English Grammar Secrets by Caroline and Pearson Brown, we find the following: “We can also use ‘have to’ to express a strong obligation. When we use ‘have to’ this usually means that some external circumstance makes the obligation necessary.”

Manny Diaz would tell you that sometimes, “have to” comes from within.

“I think it was coach (Bobby) Bowden who said that you won’t make it as a coach unless you HAVE to coach,” he said.

And there begins our story.

“Sports was a big part of my life growing up,” the Longhorns’ new defensive coordinator and linebackers coach recalls. “I was one of those guys who learned how to read by reading the sports page in the morning.”

His early education came from Miami Country Day School, an elite college preparatory private school that begins at age three and continues through high school. Fewer than 1,000 students are enrolled in the historic institution that was founded in 1938.

“The classes were so small, so if you were in athletics you had to play on multiple teams. When the football season ended, we would all move to playing basketball. Then, from the basketball court to the baseball diamond. So it gives you a chance to be involved in a lot of different things–probably more than most people would think.”

But where some kids grow up imagining themselves playing sports at the highest level, Manny Diaz dreamed of telling about it.

“A lot of people grow up who don’t really know what they want to be. It dawned on me midway through high school that I just wanted to be in journalism in some way, shape or form. I had already talked to people that had worked at TV stations. I was writing for the school paper. Everything was on that line. That’s part of why I chose a large university.

That is why he chose to travel northwest from Miami, to Tallahassee and Florida State University.

“I wanted to be in a big place where I was able to cover big time events,” he said. Once there, it seemed the beginning of a charmed life. “It was one of those many, many breaks that I had–it’s funny how things happen in your life.”

In the fall of his freshman year, the school newspaper at Florida State lost its credibility with the administration. After a series of articles, readers and supervisors had had enough, and the school decided to start another newspaper on campus. So a call went out for volunteer writers, and at the front of the line was Manny Diaz.

“It was an amazing opportunity…one of those things that just kind of falls from the sky. I got a job as a sports writer and was covering the NCAA Baseball Regionals in the spring of my freshman year in college. The next year I was covering the football team. My third year I was sports editor of the paper, [and] I had a TV show on the campus TV station. Everything was going exactly according to plan. It was why I had come to Florida State. My third year we won the National Championship in football. I was on the field at the end of the game. The whole thing was like a dream.”

Then, another turn came. Florida State’s communications degree accepted journalism courses from cross-town Florida A&M, and in a speakers’ series there he met Pam Oliver of ESPN.

“We wrote mock articles and did other work,” Diaz recalls, “and at the end of the seminar she encouraged me to apply for an internship at ESPN. That was the second thing that fell from the sky.”

The selection process for the internship began with a phone interview, and then, Manny was one of a dozen hopefuls chosen to go for in-person interviews at ESPN’s headquarters in Bristol, Conn. The test there was about sports knowledge. Diaz handled the questions about the NFL and the major league baseball teams, but was stumped when they asked him who was going to win the National Hockey League’s Vezina Trophy. Then, the straightforwardness that would eventually endear him to prospective employers such as the Longhorns’ Mack Brown took over.

“I have to be honest,” he said. “We don’t get much hockey coverage down in Florida, and I have no idea what the Vezina Trophy is for.”

But told that it went to the NHL’s top goalie, he proceeded to rattle off the names of outstanding goalies in the league. Still, when he walked out, he figured his chances were slim.

“I figured one of the other 11 would know what the Vezina Trophy was, so I figured I was done,” he remembered. When he got back to Miami, however, he got a call from ESPN. He had won the internship.

He returned for his senior year at Florida State, and when graduation came, he called ESPN and they hired him without an interview. Manny Diaz, the youngster from Miami who had dreamed of covering “big time” sports, had made sports television’s “big show.”

Immediately, the rising star was grabbed up by ESPN’s NFL show, which at the time was the lynchpin of the network’s coverage. He worked the 1996 season breaking down films and putting together production features. It was then that announcer Sterling Sharpe, a former college and NFL star, told Diaz that if he ever went into coaching, he was taking Diaz with him.

That began to stoke an emotion for Diaz. Finally, at the Super Bowl, the flame burst out.

“We were interviewing Bill Parcells,” he says. “And I remember thinking this was my big moment. On the one hand, you are working for ESPN, and you have made it. You are at the top of your profession. But then, if you are getting interviewed by ESPN AND coaching the Super Bowl, you have made it to the top of the coaching profession.”

So the question became, “which one would you rather be? And it was obvious. From that moment on, anything I was doing working toward the ESPN chair was denying what I really wanted to do.”

At the time, he had sent out prospective interview tapes to television stations. Had one responded, his career as a coach would likely not have happened.

“I had been at ESPN for two years, and I think if I had been there two more months I might have gotten a promotion to the next level. And once I had that, I don’t know if I would have ever left,” he says.

His wife, Stephanie was using her degree in hospitality management from Florida State. She was running a restaurant in Bristol, and was six months pregnant.

“It’s funny how, looking back, how youthful naivete can get you a lot of places, because you have no idea what all it takes to get into this deal. It wasn’t the most well thought out plan in the world. I had no idea how [being a] graduate assistant worked…had no idea how staffing worked. I just showed up at Florida State. I knew of the coaches from interviewing them, so I just went back and wanted to throw myself on their doorstep and see what I could do,” he remembers.

The first answer was “nothing.” NCAA rules govern the size of football staffs, and volunteer coaches are not allowed.

“So I said `that was a great plan.'”

Still he pursued the dream. He started taking courses in coaching while Stephanie enrolled on a path that would eventually earn her a master’s and PhD in sports administration. Diaz was working with a high school basketball coach at one of the main high schools in Tallahassee, and came close to getting the JV job there. Again, it was the turn in the road that he didn’t take that made all the difference.

Florida State found that he could do clerical work in their football offices. For the entire 1997 season, he worked as a data entry employee in the Child Support division for the state of Florida in the morning, grabbed lunch and then headed to the football offices. But when he proved to the football staff that he was willing to do anything from picking up recruits at the airport to stuffing envelopes, he finally got a job as a graduate assistant. Just as he had done with the NFL films in his “other life”, he was breaking down video tapes and doing the duties now handled at colleges under the job description of “graduate assistant” or “quality control.”

The biggest break came when Florida State needed an on-the-field grad assistant, and the obvious candidate was right there on their staff–Manny Diaz.

A lot of his strength comes from his roots. His parents had divorced when both they and Manny were very young. He was reared by his mom, a cardiac cath lab nurse, and his stepfather. His father, Manny, Sr., was the son of Cuban refugees who had fled their native land in the late 1950s.

The admiration for his parents is obvious, as is his respect for those who dared to cross the water from Cuba.

“Those people came over with nothing. They were teachers, doctors and lawyers who were at the top of their profession. Then they had to get to the back of the line. They had to fight to get their way back up,” he said. People will say `but your dad was the mayor of Miami.’ That was in the last ten years. When I was growing up, he was re-inventing himself.”

Reared in the home with his mom and step-dad, and attending Miami Country Day, he found the environment that would drive him. And when he got to Florida State, he got the motto that would become his benchmark.

You get what you demand.

When he left Florida State to become a full-time assistant coach for the first time, he had a new revelation.

“I had been at ESPN, and they were the industry standard. I went to Florida State, and they were the industry standard. We lost three games in three years. We had lost one national championship game and won another. It was an amazing time to be there…an amazing time to learn. So when I got to NC State with Chuck Amato, it was valuable because it was the first time I saw why people lose. I got to see how a program got built from day one, and it was really fascinating. That’s where you start to see that everybody says the same things. You go to everybody’s football practice and nobody’s teaching the guy to go the wrong way. Everybody does an off-season program. Everybody lifts weights. Everybody does the same more or less drills in practice. Everybody runs one style of offense or the other. There is nothing that guarantees success. It is how you do it. The thing that jumped out at me is the attention to detail. That’s what I saw at ESPN. We would do a four minute feature and show it to the boss and there would be a half second of video that’s he didn’t like, and we would have to redo it. Nobody watching television would ever notice a half second of video.

“At Florida State it was the same thing. A drill was all the way right, or it was all the way wrong. And if anything was not exactly the way it was supposed to be done, it was done again. And when we got to NC State, that was a surprise to those players. They had not had that level of accountability…to do everything exactly right. In the six years I was there we got the program to a different level.”

In the years since he became a Graduate Assistant at Florida State, Diaz has coached teams that have appeared ten bowl games. He followed his tenure at NC State with stints as defensive coordinator at Middle Tennessee and Mississippi State.

Stephanie and Manny have three sons, Colin, Gavin, and Manny.

They have taken the values of their upbringing into their family today.

“What I learned from my mom and stepdad and my dad was to be loving, and that’s the most important thing in parenting. It is to have your children be inspired and follow their dream and keep the lights on at your house.

“Leaving ESPN, almost becoming a JV coach…it doesn’t seem to add up. The string of variables that have to go your way to make it to a place like Texas…you have to sit back and you have to believe one of two things: it is an extraordinary amount of luck, or it is the hand of God, and I am more willing to believe the latter. These things don’t just happen.”

What he has learned in the process of “re-inventing himself,” is that the road Manny and Stephanie Diaz traveled has truly been a journey spotted by those who have touched their lives.

“Both at ESPN and at the places I have coached, I have been fortunate to work with great people. It is not about buildings or logos, which history had proven.

“If you love your profession, you will never work a day in your life,” he said. “Coaching is an outstanding occupation. It is a hard profession. It’s funny when you think back about the way I got into coaching football, because I was a fan first, and when I was a fan I didn’t know what I didn’t know about this game. You think you know, and you find out and realize how little you knew. There are certainly things that affect my philosophy that I remember from being a fan. When you start a restaurant, you are going to revert back to the type of food that you like and there are certainly some things about the aggressiveness of our defense that if I were sitting in the stands I would want them to do. I have been blessed to work with great people who had similar philosophies. And the coaches I have worked for have just let us go. There are things that we do that are exotic and unusual, and we turned those into our strengths. It almost became fun to stay ahead of the curve and do weird things.”

It is what happens when you re-invent yourself, and when you have to coach.

05.30.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Memorial Day

May 30, 2011

Editor’s note: The following article is a reprint of a classic Bill Little commentary that originally appeared on May 25, 2008.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

“In Flanders Fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields.”

Sitting in the back of an ambulance near a battlefield in France, a Canadian doctor, Lt. Col. John McCrae looked out on a cemetery where a gentle breeze stirred the wildflowers that provided the imagery for this classic poem of World War I. A friend lay buried in the field, one of thousands who died in what was called “The Great War — the war to end all wars.”

Sadly, that lofty goal has never been realized.

“The torch” has been passed from generation to generation. Brave men and women stand today in harm’s way, fighting to preserve the life we know.

Memorial Day is, and should be, a day of honor. Since the days of the War Between the States, this has been a day of remembrance for those who have died in our nation’s service. And in that space, history both mourns, and applauds, who they were, and what they did.

And as the massive remodeling of Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium nears its completion during this summer, what started in 1924 as a concrete edifice dedicated to those Texans who died in World War I re-emerges as a majestic monument to them, and to all those men and women who have served our country in any foreign conflict.

Juxtaposed with the Louis Jordan Flagpole in the southeast corner of the stadium (a monument honoring the first former Longhorn killed in World War I) are a plethora of significant factors that recognize the value of leadership, as well as the importance of history. The stadium veterans committee is already working on a re-dedication of the stadium this fall, as well as a plaza outside the north end that will serve as a special place to remember the veterans and memorialize those who died.

Mack Brown‘s office contains a healthy supply of pictures and flags sent by Longhorns serving in the Middle East, and the stirring memory of Marine Ahmard Hall carrying the American flag onto the field started a tradition that is repeated each year.

About a month ago, Coach Brown sat in his coaches’ conference room talking to more than a dozen touring cadets from the United States Military Academy at West Point. The subject had to do with teamwork and leadership.

A little over ten days ago, Penn State coach Joe Paterno and Hall of Fame wide receiver and Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate Lynn Swann came to Austin to help celebrate the launching of a Distinguished Chair in Leadership in Global Affairs in Mack Brown‘s name.

The Chair will be connected to the LBJ School of Public Affairs, and it is not without irony that one notices that the LBJ Library and the stadium — two of the three most recognized structures on the UT campus (the Tower being the other) — sit across the street from each other.

The students who helped raise the money for the construction of the original Texas Memorial Stadium did not have the benefit of today’s technology to understand about “global affairs.” All they knew was that school mates had died in faraway fields whose names they couldn’t pronounce.

It was a big, big world, then.

Today, instant communication and travel have made the world a lot smaller, and yet larger with the challenges. And as Mack accepted the honor of the Chair named for him, he acknowledged that leadership cannot come without teamwork, and teamwork is about relationships. All of which goes back to the benchmark principles of his football program — communication, trust and respect. All applied with a common purpose.

Global affairs have to be about all of that. That is the power of education, the reason for reasoning. But as we dream of a world where we can all work together, it is important to remember that reality says there will be a time where, despite the best of efforts, men and women will have to stand and fight against the demons of greed and jealousy.

That is why, on the lake or at the barbecue or at some distant outpost where death bids hard to take the valiant, it is important to understand what Memorial Day is all about.

The men and women of the United States Armed Forces fight, not to make war, but to achieve great peace. Death is, and always will be, a part of the reality of war. That is why, on Memorial Day, America pauses to honor those who have lost their lives in battle.

Because the men and women we honor, whether it is amid the white crosses at Arlington Cemetery or a family plot in a little town in West Texas, died fighting for our freedom.

And there is no thanks great enough, or memorial big enough, to repay them and their families for that.

Or, as another poet wrote as a reprise to McCrae’s poem, “We cherish too, the Poppy red that grows on fields where valor led, it seems to signal to the skies that blood of heroes never dies.”

05.17.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: One heckuva man

May 17, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In a land of giants, Doug English always came up big.

Tuesday, the former Longhorn all-American and four time NFL Pro Bowl tackle, reached the pinnacle of the collegiate sport when he was named to the 2011 class of the College Football Hall of Fame of the National Football Foundation.

English will become the 16th Longhorn player and 18th Texas inductee, including coaches Dana X. Bible and Darrell Royal, to be enshrined in the College Hall of Fame, which recently moved from South Bend to Atlanta. The 14 new members and two coaches joining the Hall will be welcomed at a banquet at The Waldorf=Astoria Hotel in New York City on December 6.

A team captain and the Most Valuable Player of the 1974 Longhorns, Doug earned consensus all-American honors his senior year, and was a two-time all-Southwest Conference selection at Texas in 1973 and 1974. The 6-5, 260 pound tackle was a second round draft choice of the Detroit Lions in 1975, and for ten seasons he was one of the best, and most popular, members of the Lions’ team.

He was named to the NFL Pro Bowl as an all-star following the seasons of 1978, 1981, 1982 and 1983, but was forced to give up the game following a neck injury he suffered in a game on November 10, 1985.

His induction puts a final stamp on the faith held in him of his college position coach–and the man who recruited him to Texas–the late R. M. Patterson, who died in December of 2009.

Patterson found English after he had finally gotten on the field his senior year at Bryan Adams High School in Dallas.

“He was a lanky, tall fellow that ran hard and worked hard to get to the football,” Patterson remembered during English’s senior year at Texas. “I thought someday he might be a 6-5, 260 pound lineman with tremendous potential.”

And that is exactly who he became.

“I liked what I saw in every way,” Patterson said then. “He just came from an all-American family. You know any person who has great ability will be a natural leader. But when you get a real exceptional person with a great attitude as well, you’ll almost always find good results, whether it’s in football, or in any aspect of life.”

Jerry Green, the long-time respected columnist for the Detroit News, saw the same gifts in English. When English was forced to retire from pro football in May of 1986 because of a ruptured vertebra, Green wrote a column entitled, “Lions lose a class act in English.”

“You are not allowed to make too many friends among the athletes in this journalism business,” wrote Green. “The athletes have to be choosy and so do you. Doug English was a rare friend.”

Twenty-five years later, Green and fellow sports writer Mike O’Hara of the Detroit News still agreed.

“Doug English made such an impression on Detroit that 25 years later he is still remembered,” says O’Hara. “I will use the words of his former coach, Monte Clark, to describe him: `Doug English is a cut above the guys who usually came through as professional football players. ` He was a great player, and a great guy. When they named an all-time Detroit Lions team for their 75th anniversary, Doug was on it.”

He was on it, both sports writers would add, for all the right reasons.

When he returned to Austin after his playing days were over, English got involved in business activities, but still found time to support numerous charities, including one that is involved in research of spinal cord and traumatic brain injuries. In 1998, he served as a member of the search committee which recommended the hiring of Longhorn football coach Mack Brown. He is active in the NFL Alumni Association in Austin, and now spends most of his time with his ranch and his family.

“First of all, he was a human being,” says Green today. “He was a great person as well as a great football player. We would go to dinner together once a year, and would talk about everything and anything except football. He had manifold interests. I really appreciated him. He was a wonderful pro.”

Jay Arnold, who played with English at Texas during the 1972 and 1973 seasons, remembers a teammate whose work ethic would be his lasting impression. It came naturally: when English was in junior high, his coaches cut him from the eighth grade squad. But English just kept coming back, and finally, the coaches agreed he could be on the team.

“He practiced as hard as he played,” remembers Arnold. “And he led by example. He expected all of us to give as much as he did. I remember watching the film of an Arkansas game his sophomore year. He had been sick and hadn’t practiced all week. Arkansas was at our goal line, and it was fourth down. They decided to run right up the middle. On the film, it looks like a bomb exploded. Doug crashed through everything and made the tackle behind the line of scrimmage. Plays like that were pretty commonplace for him in his later years, but I remember all of us looking at that video and thinking he was going to be a really special football player.”

For English himself, joining the elite of college football is more of opportunity than an accomplishment.

“One thing that being able to split a two-gap and bring down a guy with one hand provides is a chance to help young people,” said English, who was one of the most consistent tacklers at Texas and in the NFL, ripping down ball carriers with hands that were as big as baseball gloves. “You get a chance to pat a young player on his back and say `good job’ and `are you doing your homework?’, and they will listen to you more than they will 900 counselors and advisers because you enjoyed success as an athlete. In that, you may be able to do some good.”

It is not without irony that English once played the lead in a movie called “Big, Bad John.” It co-starred country singer Jimmy Dean, and was based loosely on Dean’s song about a miner who became a hero when he used his mighty strength to rescue some co-workers trapped in a mine disaster.

“The only important thing sport can leave you is a chance to make a difference for people,” English said Tuesday. “This is a chance to represent your school, but it is also a chance to represent those teammates who worked so hard with you. It is good for people whom you care about.”

Through his example as a player, his character and reputation as a person, and his commitment to charities which make a difference to others, English personifies the big man who lifted those timbers in the song.

The day English retired from the Lions, he said this to Jerry Green:

“Life is an experiencing of emotion. Technically, you can take a computer and hook it up to a corpse and make it talk, make it breathe – do things that people do. But it wouldn’t have emotions.”

That is why Doug English’s cell phone was full of messages Tuesday. It is why he called his old coach, Darrell Royal, to thank him. And it is why there will be smiles, and there will be tears, each time he is honored as the newest Longhorn member of the National Football Foundation’s College Football Hall of Fame.

05.06.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The cornerstone — A story of Bennie Wylie

May 6, 2011

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of articles on the new coaches for the Texas Longhorns football team.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

It is not without irony that any discussion of the phrase “it takes a village to raise a child” seems to place its origins either as an African proverb, or a historical root of Native American tribes. Either way, Bennie Wylie is good with it.

That is the way life was for Wylie when he was growing up in Mexia, Texas–a town of 6,500 in an area of farms and folks located at the base of the Great Plains, 45 miles east of Waco and 85 miles south of Dallas. Settled in the 1800s, it was once the home of settlers, buffalo herds, and Plains Indians.

And in his eyes–and those of hundreds of kids who grew up in the local elementary school–the most important man they ever met was not measured by stature in the community or great wealth. He was measured by his wisdom, and his heart. He was the elementary school janitor, Bennie Wylie Sr.

“I guess my life started by just watching my father, who passed away five years now,” says Bennie Wylie, the new Strength and Conditioning Head Coach for Football for the Texas Longhorns. “Just to watch how hard he worked and didn’t complain. He grew up watching whole generations as they went through school. He helped every kid in my town. He taught them how to tie their shoes and wiped their eyes when they cried. Every little kid knew Mr. Wylie.”

Bennie Wylie may have grown up with a dad who worked extra jobs after the school closed just to make ends meet, but he grew rich in spirit. And he learned a work ethic that burns deeply within him today.

“Dad would spend all day at the school, and then after work he would go mow yards. He’d do all this stuff to help us. Then we would throw hay, and we had a friend who would let us prune their trees. Dad worked to get us to where we could, not have nice things, but just so we could eat,” Bennie says.

At the same time, his mom worked just as hard, rearing Bennie and his brother and sister and taking odd jobs in home health care after Bennie, the youngest child, was in school.

“I didn’t really know it then, but as you look back, you realize all the things they had to give up just to make sure we were okay,” he says.

The one family vacation he remembers taking was the 85 mile trek to Dallas when he was seven years old to see his grandfather.

But while all of that may seem dire, it would be the village who would raise the child.

His third grade teacher, Sheila Phillips, told him, “Bennie, be well rounded. Be good at a lot of things.” And so he was.

The first time he left the state of Texas was when he was 15. He was a member of a Texas all-state church choir that traveled to Disneyworld in Florida. The third grade teacher’s advice was taking: he excelled in education and music as well as sports. Playing both the trumpet and the tuba, he was the band captain in high school, as well as the football team captain. He was an Eagle Scout and was on the student council in high school.

The modern day example of a Renaissance Man, he did everything well, and had a wide circle of friends.

“I was never just a jock, and I was never just a nerd. I was just ‘Bennie’. To everybody,” he says.

The commitment he carries into the Longhorn football strength and conditioning program came from a variety of disciplines.

“I guess I learned discipline from a lot of people. It was kind of like a village that raised our kids in our town. My parents helped raise our friends. I was raised by my friends parents, by my pastor, by my youth minister, by my scout master, by my head coach. Everybody had a part of the discipline. Everywhere I went, everybody expected a certain thing, and you had to live up to all of these different people. My scout master expected me to make Eagle, and I was the first African-American that made Eagle Scout in my whole area. He made sure I did that. I had a pretty decent voice then, and my youth minister made sure that I wasn’t just going through the motions and riding through…he wanted me to be the best. My band director wanted to make sure I wasn’t just second chair because he knew I could be first chair. I got pushed by everybody in our life.”

And the ripples of the message carried far beyond the small town.

“I have two best friends that I call brothers who were Navy SEALS. Their discipline, their work, and that of all of our men and women in the military inspire me. They do what they do so that we can do what we do here,” he said.

It is that kind of commitment, that kind of discipline, that leads Wylie to the task he now faces: helping the Longhorn football team rebound from a disappointing season.

“People often ask, ‘Are kids different today?'” says Wylie, who at 34 is part of the new young staff for Mack Brown‘s University of Texas football team. “There are different stimuli than when I was growing up, but kids are kids. They are a product of their environment. If we let them watch all the TV in the world, then they are influenced by that. If we don’t discipline them, then they get away with that. Our student-athletes here are incredible, because we expect a lot. We demand that they go to class, we demand that they are good citizens outside of here, and so they do it. In a way, it’s weird that we are a great program and have very few issues, but that’s what we demand of our team. Kids will give you what you ask of them. If you don’t ask very much, then they won’t give you very much.”

In his years with the Dallas Cowboys, at Texas Tech and at Tennessee, Wylie gained a national reputation for his own conditioning. But he says it isn’t the body that makes the difference–it’s all in your head.

“I am intrigued by the mind,” he says. “The body is just a machine. It will do some amazing things, but the brain–the soul, the spirit–drives the machine. And that is my edge. That’s my strength. I have a strong mind, and I will make my body do things it probably should not do any more…that it can’t do. And hopefully, that’s what I can pass on to the team–that your body will do what your mind tells it to do.”

Having worked with superior professional athletes such as Troy Aikman, Emmitt Smith and Darren Woodson, Wylie understands the drive it takes to excel.

“We’ve all seen great athletes with great talent that do nothing with it. So to me, that mental edge is the difference. There is a little man in your head and he can talk you into, and out of, a lot of things. So are you going to listen to that little guy when he tells you to stay in bed? It’s early, and you don’t have to get up. Or the little guy tells you this is too heavy. Don’t lift this…you have a little ache here…don’t finish through the line, just pull up. We all hear that little voice, and to me, that’s what makes the human being incredible, because that little guy in your head runs the whole thing. You have to conquer him.”

Wylie, a former tailback at Sam Houston State is married to a great wife, with twin sons. He says the strength and conditioning room is like a microcosm of life –“truth and reality and production.”

“You can tell me that you are going to bench press 400 pounds, but you have to show me. This room is humbling. It’s about working, and it’s about getting better.”

While NCAA rules prohibit Mack Brown and his football coaching assistants from working with the players in the summer, they do allow the strength and conditioning coach and the trainers to be present for volunteer workouts. But Wylie would be the first to say that while the summer workouts are “Bennie’s time,” that’s a long way from it becoming “Bennie’s team.”

“If we are a coach-driven team, we are not going to be very good. This is a player-driven team, and it needs to be that way. Coach Brown gives me the honor of giving me his team to train and take care of. It’s like your Dad gives you the keys to the Porsche. You can drive it, but you better not scratch it or wreck it. It’s great that you get to drive a Porsche, but you are really excited when you get to hand him the Porsche back and there’s not a scratch on it. It’s in perfect condition, just like he gave it to you. It’s a huge responsibility for him to trust this football team with not just me, but our entire strength and conditioning staff. There are a lot of guys and girls that work down here that push this team. They are here at five in the morning, and they stay late just like I do.”

So what does the summer look like for the Longhorns of 2011?

“I hope they don’t like me most of the summer, because I am going to challenge them, I am going to push them to the edge, trying to get them outside their comfort zone. We are going to put them in situations where we feel we are going to get into at some point in the season, so we can learn how to work through those things and learn how to react to them and respond the right way. It will be tough. We are going to work hard, because when you have pain and a little bit of suffering and you do that together, it forms this football team.”

In a conversation during the spring with new co-offensive coordinator Bryan Harsin, a brainstorming session turned into a philosophy and a season’s theme of “brick by brick.”

“When you build up a building, you have to have that foundation, and I think this program will always have that solid foundation. Our building got shaken a little last year. So instead of Coach Brown saying this is panic mode, he’s saying ‘let’s build this thing up, one brick at a time.’ And that’s what we have been doing since we’ve started. You have to know that it is going to be a process. You can’t just jump to the roof. We have to lay each brick, train hard, take care of our bodies, be smart with all of our school work. We have got to put all of these things together or we are not going to have that end product that we wanted,” Wylie said.

As a dad, his goals for his children are simple.

“I want them to have a better life than I did, but I want them to go through life and have some hard times, because that’s what made me who I am. I don’t want them to go through life and have a fluffy, carefree ride. I want them to have the things they need to deal with and work through just to make sure they are tough. I will try to provide more for them than I had. I want them to be good citizens. I don’t care if they are good in sports. We don’t push them into anything. If they are good, we’ll support them, as my parents supported me. They taught me to never quit anything. If I was in it, I was in it,” he says.

While the players marvel at his determination and endurance to run and work out with them as if he were 15 years younger, Wylie still sees himself as the teacher and friend who guides them on their way.

“I am just a blue collar kid from the country,” he says. “I am just going to do my part and push our team from the back, and let our players drive the team. When you bring energy and excitement and you are willing to work hard, only good things are in store for us.”

It is his role, and his legacy. Part of the village, grown from the roots of a humble man who never considered what he did; but lived and thrived, on who he was.

02.11.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Pipe dreams — Remembering Emory and the Wishbone

Feb. 11, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

It was the baseball season of 1968, and I had just joined the Texas Longhorn athletics staff as Assistant Sports Information Director. Texas was playing Rice in Houston, and I had agreed to meet my favorite uncle for breakfast at the legendary Shamrock Hilton Hotel. I was there with our baseball team; Uncle Clarence was there because my cousin’s husband was in the hospital at the fledgling medical complex which would later become world renown.

“How’s Gale?” I asked.

The usually cheerful face darkened as he said somberly, “Gale is a very sick man.”

It was then that I learned that my cousin-in-law was battling a disease with a very long name that for practical purposes had been shortened to its initials: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis was becoming known as ALS. I would learn in time that one of my heroes, Lou Gehrig, had died of it. And within three years, so would my cousin’s husband.

That was 40 years ago. Modern medicine has solved a lot of things in those years, but sadly, curing amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is not one of them. That is why we were all devastated to learn that Emory Bellard, an icon of the coaching profession, was fighting the uphill battle that matches modern medicine and the disease. Thursday, the disease won.

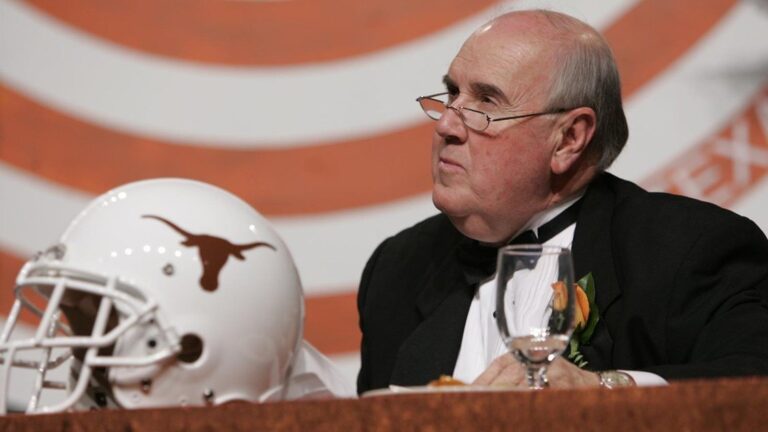

Just two years ago, Emory had attended a Sportsman’s Club dinner previewing the Longhorns’ upcoming season and honoring the 1969 Texas National Championship team. His hair was snowy white, and the ever-present smoking pipe which had been his trademark was gone. Otherwise, he was the usual, ultimate gentleman. A master of the game and a citizen of the people. And in this space, I remember another place, and another time, when the faces of Texas Longhorn football, and the mindset of the college and the high school game, were about to change.

It was the summer of 1968, and Emory Bellard sat in his office, down the narrow, eggshell-white corridor that was part of an annex linking old Gregory Gymnasium with a recreational facility for students. There were two exit doors, one at the glassed-in front of the two-story building, and the other at the end of the hall.

Summer, in those days, was a time for football coaches to relax and to prepare for the upcoming season. Summer camps for young players were years away, and few of the players were even on campus. Most were home, or working to earn extra spending money to last the school year. Most of Bellard’s cohorts on Darrell Royal’s staff were either on vacation or had finished their work in the morning and were spending the afternoon at the golf course at old Austin Country Club.

Texas football had taken a sabbatical from the elite of the college ranks in the three years before. From the time Tommy Nobis and Royal’s 1964 team had beaten Joe Namath and Alabama in the first night bowl game, the Orange Bowl on January 1 of 1965, Longhorn football had leveled to average. Three seasons of 6-4, 7-4 and 6-4 had followed the exceptional run in the early 1960s.

Despite an outstanding running back in future College Football Hall of Famer Chris Gilbert, the popular “I” formation with a single running back hadn’t produced as Royal and his staff had hoped. So with the coming of the 1968 season, and the influx of a highly touted freshman class who would be sophomores (this was before freshmen were eligible to play on the varsity), Royal had made a switch in coaching duties.

Bellard, who had joined the staff only a season before, after a successful career in Texas high school coaching at San Angelo and Breckenridge, was the new offensive backfield coach.

He had gone to Royal with the idea of switching to the Veer, an option offense which had been made popular in the southwest at the University of Houston. As the Longhorns had gone through spring training, they had returned to the Winged-T formation which Royal had used so successfully during the early part of the decade.

So, as the summer began, the on-going question was, who was going to play fullback, the veteran Ted Koy, or the sensational sophomore newcomer Steve Worster? With Gilbert a fixture at running back, even in the two-back set of the Veer formation, only one of the other two could play.

And that is how, on that summer afternoon, the conversation began.

“So, who are you going to play, Koy or Worster?” I asked. Bellard took a draw on his ever-present pipe, cocked his chair a little behind the desk that faced the door, and said, “What if we play them both?” He took out a yellow pad and drew four circles in a shape resembling the letter “Y.”

“Bradley,” he said, referring to heralded quarterback Bill Bradley, as he pointed to the bottom of the picture. “Worster,” he said, indicating a position at the juncture behind the quarterback. “Koy”, he said as he dotted the right side, “and Gilbert,” indicating the left halfback.

Royal had told Bellard he wanted a formation that would be balanced, and that, unlike the Veer which was a two-back set, would employee a “triple” option with a lead blocker. On summer mornings, Bellard would set up the alignments inside the old gymnasium next to the offices, using volunteers from the athletics staff as players. When the team members came back at the end of the summer break, Bellard took Bradley, James Street, Eddie Phillips and a fourth quarterback named Joe Norwood to the Varsity Cafeteria next to the gymnasium. There, as they sat at a table in the back of the room, Bellard arranged some salt and pepper shakers and the sugar jar in the shape of a Y. Then he explained the concept.

When the players tried it on the field for the first time, Street remembers saying with Bradley, “this ain’t gonna work….”

Still, Bellard persevered. As fall drills began, the formation was kept under wraps. Ironically, Texas opened the season that year against Houston. It was only the second meeting of the two. The Longhorns had won easily in 1953, but the Cougars had established themselves as an independent power that was demanding respect from the old guard Southwest Conference.

A packed house of more than 66,000 overflowed Texas Memorial Stadium for the game, which ended in a 20-20 tie. The debut of the new formation didn’t exactly shock the football world. A week later, Texas headed to Texas Tech for its first conference game, and found itself trailing 21-0 in the first half. It was at that point that Royal made the first of a series of moves that would change the face of his offense and the face of college football, for that matter.

Bill Bradley was the most celebrated athlete in Texas in the mid-1960s. He was a football quarterback, a baseball player, could throw with either hand and could punt with either foot. He was a senior, and when Royal unveiled the new formation, he thought that Bradley’s running ability would make him perfect as the quarterback who would pull the trigger.

But trailing in Lubbock, Royal made one of the hardest decisions of his coaching career. He pulled Bradley and inserted a little-known junior named James Street.

A signal caller from Longview, Street had been an all-Southwest Conference pitcher in baseball the spring before, but no one could have expected what was about to happen.

Street brought Texas back to within striking distance of the Raiders, closing the gap to 28-22 before Tech eventually won, 31-22. Bradley would eventually move to defensive back, where he became a star in the NFL.

Back home in Austin, the staff met to adjust where the players lined up in the new formation. In a debate that was won by offensive line coach Willie Zapalac, the fullback position alignment was adjusted. Worster, who had been lined up only a yard behind the quarterback in the original formation, was moved back two full steps so he could better see the holes the line had created as the play developed.

Against Oklahoma State the next week, Texas won, 31-3. Nobody realized it at the time, but that would be the start of something very big. With Street as the signal caller, that win was the first of 30 straight victories, the most in the NCAA since Oklahoma had set a national record in the 1950s, and a string that held as the nation’s best for more than thirty years.

Today, James Street is one of the nation’s most successful structured settlement money managers, and in countless public speeches, he uses things Bellard taught him–not only about the game, but about life.

“Emory,” Royal recalled Thursday, “understood the game of football, and was a great coach. But beyond the X’s and O’s, he was a great teacher.”

A teacher, Street says, of more than just the game.

“Before every game he would tell me `stay steady in the boat,'” Street recalled. “‘Play every play like it’s a big play. Don’t worry about the outcome of the game. Just play every play like it’s a big play.'”

The offense Bellard designed became a staple for colleges and high schools in the 1970s and on into the 1980s. Bear Bryant at Alabama and Chuck Fairbanks and Barry Switzer at Oklahoma would use variations of it to compete for national championships. Bellard would run it successfully as a head coach at Texas A&M and Mississippi State. The service academies–most notably Air Force–would use the concept with good results for years.

Bellard, whose highly successful high school career included a record of 136-37-4 and three state championships, left Texas after the 1971 season for his head coaching stints at Texas A&M and Mississippi State. He eventually came out of retirement to return to his roots as a high school coach before retiring for good as he neared his 80s.

Mack Brown remembers him from his time as a coach at Mississippi State, when Mack was coaching at Tulane. Most of all, he remembers his contribution to the history of the game, and to his dedication to help young coaches whenever they asked.

They will hold a memorial service on Saturday, February 19, at the First Baptist Church in Georgetown. There’ll likely be a gathering of Longhorns, from his five years as an assistant here, as well as Aggies, for his years as a head coach there. There will be those who remember the Wishbone, and the legacy it left.

More than that, however, they will recall the patience of a pipe smoker, who in his own way was an artist of the game, as well as a teacher. There is a touch of sad irony as well. With Bellard’s passing, seven of the eight assistant coaches on that staff which changed the face of Texas football are gone. Tom Ellis, Bill Ellington, Mike Campbell, Leon Manley, Willie Zapalac, and R. M. Patterson preceded Emory in death. Only Fred Akers remains.

And through his legacy – like all of them – Emory, with his pipe and his yellow pad, his schemes and his dreams, will stand the test of time, not only for what he did, but for who he was–and the lives that he touched.

01.22.2011 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Arranging the deck chairs

Jan. 22, 2011

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

The preacher lady turned to the philosophy of the “Peanuts” comic strip Sunday morning, and I couldn’t help but think of how it related to the month Mack Brown has spent in his quest to rebuild his Texas Longhorn coaching staff.

It seems Charlie Brown’s adversary, Lucy, has asked the following question: “Charlie Brown, life is like a deck chair on a cruise ship. Passengers open up these canvas deck chairs so they can sit in the sun. Some people place their chairs facing the rear of the ship so they can see where they’ve been. Other people face their chairs forward—they want to see where they are going. On the cruise ship of life, which way is your deck chair facing?” she asks.

Replies Charlie Brown, “I am working on getting one to unfold.”

Starting before the season ever ended, Mack Brown was working on the chair issue. To say that he was not satisfied with the way things turned out for the Longhorns of 2010 would be a gross understatement. He wasn’t happy with his team, he wasn’t happy with his staff, but most of all, he wasn’t happy with himself. No coach in college football—or any level of football for that matter—adheres more to the philosophy that “the buck stops here” than does Brown. After 27 years as a head coach and 36 in the coaching profession, he understands the deal.

And so, with a huge dose of humility and a strong prescription of self-evaluation, he began the process of looking off the back of the ship—to try and figure out what happened.

In the days immediately following the Thanksgiving Night game with Texas A&M, he went back and looked at videos of every game. He re-watched practice tapes. He had called in highly respected friends to do the same thing and report to him what they saw. He asked for and received input from his team, and from his staff. He looked at all areas of the program. And he didn’t base it on one year—the evaluation included undetected trends that had slowly led to the erosion of the excellence.

It wasn’t as if anybody was blindsided by the actions that followed. All season, Brown warned repeatedly that things had to change. And at the end, they did. Texas was heading in a new direction. Now, it was time to turn the deck chairs toward the front of the boat. In his years as a head coach, Mack has always kept a list of coaches at every position whom he would seek out when the inevitable vacancies occurred within his staff. That would be the starting point. Then, he talked to his best friends in the business about candidates. Legendary college coaches and highly successful NFL coaches spoke with him.

As coaches resigned and chose to retire, Brown sailed through with a new look to the future of Texas football. He knew that he had a solid base in the four returning staff members—but even that was subject late in the process to what Brown refers to as “sudden change. Popular running backs coach Major Applewhite would have an expanded role in the offense. Recruiting coordinator and tight ends coach Bruce Chambers (the only original member of Brown’s staff at Texas) would be an anchor as well. Duane Akina‘s work with defensive backs and some phases of the special teams would be valuable, as would former Longhorn star and defensive ends coach Oscar Giles.

In searching for new coaches, there were some ground rules which he would absolutely observe. First, he, and only he, would know the people he was choosing as candidates. Second, he would not disrupt the staff of a team in a bowl game by wooing one of their coaches until after the game was finished. Internet and radio talk show rumors of what he was doing would abound—but none of them were true.

Immediately, he found that there are a lot of great coaches out there who would be capable and would love to work at Texas. He also learned that today’s college football is an industry where coaches are represented by agents (particularly when it comes to pro coaches), and many of the conversations with perspective candidates happened first with them.

Building a staff is like creating a mosaic. In the specialized world of college coaching, to recruit and to succeed you have to make sure you are teachers first and cover the critical positions. So you typically find the best possible coach to replace the position coach you lost. If your defensive coordinator coached linebackers, you go out and find the best possible coordinator who also coached linebackers.

For most of a month, he spent long days talking, texting, and reading resumes of coaches who might fit. A coaching staff is a critical combination of expertise, the ability to recruit, and the chemistry to blend with each other. By his own assessment, Mack never worked harder in his coaching career. And as December dwindled and the bowl games began, he had zeroed in on his top candidates.

The dominoes began to fall just as 2010 was ending. First announced was receivers coach Darrell Wyatt, who brought a wealth of experience in recruiting and a sterling background which included ten players who went on to play in the NFL.

Bo Davis came next, interviewed and announced after his Alabama team had played and won its bowl game. Chosen to mentor defensive tackles, he also brought strong recruiting ties within Texas, as well as high school coaching experience in the state.

Then came a tandem of exciting hires that continued a pattern of thirty-something men who infused both youth and enthusiasm into the new staff.

Manny Diaz had become a hot commodity on the defensive side of the ball as he had constructed innovative schemes both in his year as defensive coordinator at Mississippi State, as well as his time before that at Middle Tennessee. He had joined the coaching profession in the late 1990s, when he gave up a budding career with ESPN to work as a graduate assistant under the tutelage of the highly respected Mickey Andrews at his alma mater Florida State.

In his evaluation process, Brown had discovered that the structure of the strength and conditioning program needed to be tweaked. Jeff “Mad Dog” Madden had supervised the football program as well as maintaining duties as assistant athletics director overseeing the strength and conditioning program for all men’s and women’s sports except basketball. Nationally recognized by his peers and well-liked by the Texas players, Madden’s expanded duties had become too demanding to maintain a total focus on football. In the years since Madden had joined Brown at North Carolina and followed him to Texas, other schools had named a football strength and conditioning coach, just as Texas already had, for instance, in basketball with the talented Todd Wright.

That led to the next step—the hiring of Bennie Wylie. Wylie, a native of Mexia, Texas, who was at Tennessee for a year after helping the Texas Tech football program achieve national recognition, was the perfect fit. He perfectly fit the image—young, enthusiastic, respected by his peers and revered by his players.

Over the past several years, the biggest story in college football has been the rise to power and prominence of the football program at Boise State. In his years in the coaching profession, Brown has formed life-long relationships with other coaches. He counts retired coaches such as Darrell Royal, Paul Dietzel, Lloyd Carr, Urban Meyer, LaVell Edwards and Bobby Bowden among his close friends. But if you asked him to name one young coach whose work he greatly admires, one of the first names he will mention is Chris Petersen at Boise State.

And that brought Brown to the next major hire of the reconstruction project. Bryan Harsin had been Petersen’s offensive coordinator for five years with the Broncos. He is 34 years old, and was ready to stretch the envelope for him and his family. In a career that seems laden with destiny, he had been intrigued by Texas and Brown for some time. So when the call came to come and look at Texas, he and his wife, Kes, took the trip. There, they quickly formed a bond with Mack and Sally Brown, as well as with Major Applewhite and his wife, Julie. Together, with Harsin calling the plays and Applewhite serving with him as co-offensive coordinator, they determined they could write the next chapter in the long history of offensive football at Texas.

The sudden change factor entered when veteran secondary coach Duane Akina began considering an offer to return to the University of Arizona, where he spent 13 seasons as part of Dick Tomey’s famed “Desert Swarm” defense. When Akina finally made his decision to leave on Friday night, Brown immediately opened conversations with Longhorn legend Jerry Gray, who had college coaching experience and had spent 23 years as an all-star player and coach in the NFL. Gray had just finished coaching former Longhorn Earl Thomas while serving as the defensive backs coach for the Seattle Seahawks. The NFL had been good to him, but he was ready to come home. So on Monday the announcements of Akina’s leaving and Gray’s return to his alma mater came back-to-back, in time for Brown to tell the team as they gathered on Monday night for the first time since the break.

The final piece of the staff puzzle was put in place Thursday, when Stacy Searels was announced as the offensive line coach. Searels, who was offensive line coach and running game coordinator at Georgia, has an extensive background that included being an all-American player at Auburn, as well as experience in the NFL. His coaching stops include time at LSU when the Tigers won the national championship.

As Brown and members of his new staff hit the road visiting recruits this week, the players began early morning workouts with Wylie on Tuesday morning—the first day of spring classes. Clearly, there is much work to be done as new terminology and schemes will be installed this spring on both sides of the ball. Rarely has an in-place program undergone such an extreme makeover, with six new coaches out of the nine assistants, plus a change in the strength and conditioning area.

Last week, Brown sent his players a long note telling them his thoughts as their first meeting approached. In it, he acknowledged the fact that he is re-energized and invigorated with tremendous excitement as the spring semester begins. It is, he said, as he felt on his first day at Texas that December of 1997, prior to the 1998 season.

He has paid proper respect to the coaches who have left—all men who were a part just a year ago of what had been back-to-back runs at the national championship. He celebrates the history of Texas football on a daily basis. But he also realizes that history is a collage of both the past, the present and future.

At the team meeting, players met the new and the old staff members. As each introduced himself, he would say his name and his position, and then add in a show of solidarity: “This is my first day at Texas.” The theme—as Bennie Wylie articulated it—was “rebuilding, brick by brick.”

“I am a brick,” Wylie said, “and you are a brick.”

And that is why, with a group of young coaches who are ready to accept the challenge of the spirit and tradition of Texas football, Mack Brown has turned his deck chair so that it sails forward, into a new beginning.

12.03.2010 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The short, happy life of the Big 12 Conference

Dec. 3, 2010

(Editor’s note: As we prepare to enter a new era of college football with the final football event of the Big 12 Conference coming Saturday in the championship game, we take a look back at the beginning of the league just 15 seasons ago. The following is reprinted (with figures updated to reflect current status) from the book “Stadium Stories – Texas Longhorns” published by Globe Piquot Books and written by Bill Little)

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

Fourth and inches, & the beginning of the Big 12

As he came to the line of scrimmage and surveyed the Nebraska defense in the first-ever Big 12 Championship game, James Brown stood at the edge of history.

Or maybe, better said, he was right smack in the middle of it.

To understand the moment, it helps to understand the situation.

Our story begins long before that December afternoon 1996 in the TransWorld Dome in St. Louis. Less than three years before, there was no league championship game, because there was no league. Texas was the linchpin of the Southwest Conference, and Nebraska had become the dominant team in the Big Eight. But the college football world had been undergoing a metamorphosis that had actually been evolving since the summer of 1984.

That was when a lawsuit concerning television rights and who owned them was settled. For years, the NCAA had controlled broadcast television rights for its schools, and had distributed appearances and money as it chose. As new networks emerged with interests in covering sports, the parent organization held fast to its right to control the medium. But its member institutions, particularly the leading football powers, saw a new opportunity for both money and exposure. The universities of Georgia and Oklahoma led the way in a lawsuit, and when the court’s landmark decision sided with them, it became open season in the television market.

ESPN was a new player in the arena, but it had been limited to showing games on a delayed basis while the NCAA apportioned games to its over-the-air network partners. When the Georgia-Oklahoma decision came down, ESPN quickly began seizing properties that brought nationwide exposure to programs such as Florida State and Miami, which heretofore had limited reach.

The College Football Association emerged as the steward of the television rights for the large conferences and independent universities, and that system worked until the University of Notre Dame saw an opportunity and seized it. The Irish signed an exclusive contract with NBC, thus breaking the CFA’s control of college football weekend air time. Still, the CFA continued with a good coalition of conferences, so the issue was manageable.

But the restlessness and the positioning was a flowing stream that was not going to be denied. The dominoes began to fall in the late 1980s, and shortly after Penn State elected to join the Big Ten Conference, the musical chairs were activated.

In Austin, DeLoss Dodds was in his first decade as Texas’ athletics director, and he was recognized as one of the cutting-edge ADs in the business.

Since coming to Texas in 1981, he had watched the defection of high school recruits from Texas to other high profile schools around the country. Attendance at league games at Houston, Rice, SMU, TCU and Baylor had diminished tremendously, despite relative success on the field. When Andre Ware won the Heisman Trophy at Houston in 1989, the Cougars averaged only 28,000 fans at their home games in the Astrodome. Part of all of that, Dodds had seen, came from the turmoil caused by recruiting scandals in the Southwest Conference. But he also knew the most important figure of all: As television began to become such a powerful force financially and exposure-wise, the area covered by teams in the Southwest Conference had only seven percent of America’s TV sets. The Big Ten had thirty percent, even without Penn State. The Southeastern Conference had twenty-three percent. And the Big Eight, which had even lost its regional TV package, had seven percent.

As the dollars and the exposure opportunities began to be distributed, it was clear that the SWC and the Big Eight were in trouble.

“It usually takes a crisis to cause change,” Dodds would say later, and the crisis came in the summer of 1990 when Arkansas announced it was leaving the SWC for the SEC.

Rumors flew that Texas and Texas A&M were right behind the Razorbacks. But when folks go shopping they often visit more than one store, and suddenly, the schools of the Southwest Conference were shopping, or in a couple of specific cases, being shopped.

While the old guard of the SWC entertained the notion of raiding its neighbor to the north – the Big Eight – the progressives were imagining what it would be like for Texas and A&M to play Alabama and Tennessee. There was even a small but powerful group that wanted to see the Longhorns as part of the Pac 10. Conversations were held between Texas and Texas Tech (which was the closest geographically) with the Pac 10. Some even considered the possibility of Texas and Texas A&M going their separate ways in different leagues, but that idea quickly was dispatched as nonproductive.

Before the flame could burn in either direction – west toward the Pac 10 or east toward the SEC – politics entered the picture. The state legislature and offices even as high as the Governor’s and Lt. Governor’s squashed the idea, out of deference to the Texas schools in the SWC which would be left behind.

Discussions of expanding the SWC included in-state schools such as North Texas, and schools as far away as Louisville and as close as Tulane to the east. To the west, informal discussions included Brigham Young, which was part of the Western Athletic Conference.

The people in the Southwest Conference office made overtures to the Big Eight to form a television alliance, where the two leagues would remain intact but would negotiate a television package together. There was talk of a merger combining all of the schools, with a playoff game between the two league champs.

Dodds, however, looked beyond the money. His goal had always been to keep Texas in a position to compete for national honors in every sport. The Southwest Conference, an institution in college athletics for over seventy-five years, was dying a slow death. Attendance was down just about everywhere except Texas and Texas A&M, and in the major sports of football and basketball, recruiting was getting harder and harder. Other schools regularly raided the football-rich arena of Texas high school football, and convincing an outstanding basketball recruit to even visit was harder and harder work.

In the Big Eight, things were not a lot better. Despite the fact that both Oklahoma and Kansas had Final Four caliber basketball programs and Missouri had a nationally respected hoops program, football was still the main attraction for television and fact was, not many folks were being attracted.

In Texas, three cities ranked among the nation’s top ten in population – Houston, Dallas and San Antonio – and the television markets in Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth were in the top ten television markets in the country. Denver, Kansas City and St. Louis were the only cities in the Big Eight with any significant media markets at all. While the Southwest Conference had what was called a “regional” TV package that aired its league games over stations in the area, the Big Eight had not been able to generate one at all.

So when Dodds and Oklahoma athletics director Donnie Duncan got together to survey the landscape, they saw a far different future than those who wanted to hang on to what was.

In early 1994, the house of cards fell. The Southeastern Conference, which had added South Carolina along with Arkansas when Texas and Texas A&M chose not to leave the SWC, signed a five-year, $85 million contract with CBS. The network also signed one with the Big East for $50 million, effectively ending the CFA. The final crisis was at hand.

In the space of less than two months, the league which had begun as the Southwest Athletic Conference in 1915 was dismantled. Television negotiations pairing the Big Eight and SWC were virtually an afterthought for the networks, who were after new material. They found it when the Big Eight voted to invite Texas and Texas A&M, and with significant encouragement from Governor Ann Richards and Lt. Governor Bob Bullock, their respective alma maters of Baylor and Texas Tech.

Left behind were TCU, SMU, Rice and Houston.

Texas agreed to join the merger on February 25, 1994, and on March 10 the league negotiated a television package worth $97.5 million, the most lucrative in college football history at the time, surpassing the one the SEC had cut just a month before.

The conference began play two years later, electing to split into two divisions. The North Division was exclusively former Big Eight schools, with Nebraska, Kansas, Kansas State, Iowa State, Missouri and Colorado. In the South Division were the four former Southwest Conference schools as well as Oklahoma and Oklahoma State. And despite opposition from the coaches at all Big 12 schools, their presidents voted to have a championship game matching the division winners and sold the package to ABC-TV.

That is how James Brown came to stand with his team on the field of the TWA Dome, with less than three minutes remaining and Texas nursing an improbable lead of 30-27.

Since the league’s formation, the South Division had been viewed as simply cannon fodder for the powerful North Division. There was open resentment among some media, fans and officials in the old Big Eight toward the interlopers from the four Texas schools. So it was with a degree of irony that Texas and Nebraska, two of the winningest programs in college football, would be the first representatives of the divisions to decide the first-ever championship.

Nebraska, which, along with Florida State, would be the most dominant team in college football in the 1990s, was 10-1 and within striking distance of playing for a national championship. All the No. 3 ranked Cornhuskers had to do was eliminate the Longhorns, who were twenty-one point underdogs after winning the South Division with a 7-4 overall record.

James Brown had been a significant figure in Longhorn football. He had emerged as a hero when he got his first start and beat Oklahoma, 17-10, as a redshirt freshman in 1994. He went on to lead the Longhorns to a Sun Bowl victory that season, becoming the first African-American quarterback at Texas to start and win a bowl game.

In that 1994 season, a year that was tenuous at best for the Longhorns’ head coach John Mackovic, it was Brown who effectively turned the year – and Mackovic’s tenure at Texas – around, as he led Texas to a 48-13 win over Houston and a 63-35 victory over Baylor.

In 1995, he had piloted Texas to the final Southwest Conference Championship, including a gutsy performance despite a severe ankle sprain in a 16-6 victory over Texas A&M in the league’s last game ever. In leading Texas to a 10-1-1 record, he helped the Longhorns earn an appearance in the Bowl Alliance at the Sugar Bowl.

The Monday before the Nebraska game, Brown had walked into a press conference in Austin and stunned the media. Badgered by a reporter about the fact that Texas was a 21-point underdog and, “How do you feel about that?” – Brown finally responded, “I don’t know…we might win by twenty-one points.”

In less than five minutes, it was on the national wire.

“Brown predicts Texas victory.”

John Mackovic, who was in his fifth season at Texas, told his quarterback in a meeting that afternoon, “Now that you’ve said it, you better be ready to back it up.”

The TWA Dome was packed, with a decided Nebraska flavor for that game which would decide the first Big 12 Championship. James Brown had led his team on the field in warm-ups, and was out-cheering the cheerleaders in the pre-game drills.

Mackovic, who was known for creatively scripting his offense at the beginning of games, put the Cornhuskers on their heels immediately with an eleven play, 80-yard drive for a touchdown to open the game. Texas had led 20-17 at half, but when Nebraska took its first lead of the game at 24-23 in the third quarter and then made it 27-23 with ten minutes remaining in the fourth quarter, things looked bleak for Texas.

The representatives from the Holiday Bowl in San Diego, who had come poised to invite Texas after the `Horns were dispatched by Nebraska, had marveled at the Longhorn Band at halftime and had delivered to the Texas representatives material advertising the attractiveness of San Diego as a bowl destination site.

But four plays later, Brown hit receiver Wane McGarity for a 66-yard touchdown pass, and Texas was back in front, 30-27.

Nebraska’s ensuing drive stalled at the Longhorn 43-yard line, and with 4:41 remaining in the game, Texas got the ball at its own six. A penalty on the first play pushed the ball back to the three. Five plays later, Texas had moved the ball to their own 28-yard line.

It was fourth down, with inches to go.

Mackovic called time-out and summoned Brown to the sidelines.

“Steelers roll left,” he said. “Look to run.”

Mackovic had used his weapons well in the game. He had taken Ricky Williams, who would win the Heisman Trophy two years later, and used him primarily as a decoy. Priest Holmes, who had been the third back after coming off of a knee surgery earlier in his career, had been the workhorse.

Both players, of course, would go on to fame in the NFL, with Holmes becoming the league’s top rusher at Kansas City in 2001. Holmes finished the game with 120 yards on 11 carries, and Williams carried only eight times for seven yards. Everybody had seen the pictures of Holmes as he perfected a leap over the middle of the line for short yardage. He had scored four touchdowns that way against North Carolina in the Sun Bowl alone.

Nebraska geared to stop Holmes.

And now, there was James Brown, right where you left him at the start of this story.

“Look to run,” Mackovic had said. But as the team broke the huddle, Brown looked at his tight end, Derek Lewis, and said, “Be ready.”

“For what?” Lewis responded, as he turned to look at his quarterback as he walked out to his position.

“I just might throw it,” Brown replied.

Brown took the snap, headed to his left, and saw a Nebraska linebacker coming to fill the gap. He also saw something else. There all alone, seven yards behind the closest defender, stood Derek Lewis.

Seventy-thousand fans and a national television audience collectively gasped as Brown suddenly stopped, squared and flipped the ball to Lewis, who caught it at the Texas 35, turned and headed toward the goal. Sixty-one yards later, he was caught from behind at the Cornhusker 11-yard line. Holmes scored his third touchdown of the game to ice it at 37-27 with 1:53 left.

The next morning, Mackovic was on a plane to New York to attend the National Football Hall of Fame dinner, and to accept on national TV the Fiesta Bowl bid to play Penn State. The reaction and reception he received was amazing. In choosing not to punt from his own 28-yard line, thus leaving the game in the hands of his defense with three minutes left, Mackovic had swashbuckled his way into a significant amount of fame. Had it failed, he would have been second-guessed forever, because the Cornhuskers would have had the ball only 28 yards from the goal, where a very makeable field goal attempt would have tied the game, and a touchdown would have won it.

There is an old Texas proverb that says it is only a short distance from the parlor to the outhouse, and there was John Mackovic, sitting on a stuffed sofa in a studio at CBS-TV, accepting a bid as the Big 12 representative to the Fiesta Bowl, as Nebraska dropped from national title contention and went to the Orange Bowl.

“The call” seemingly had been seen by everybody in America. Ushers at the David Letterman show were high-fiving the Texas coach, and managers of leading restaurants were sending him complimentary bottles of wine.

James Brown had made good on his promise, even if he didn’t quite get the 21-point margin of victory. He passed for 353 yards, hitting 19 of 28 passes, including the touchdown pass to McGarity. He had led Texas to a stunning victory. The mystique of the North Division of the Big 12 had been shattered, and the guys from the South had proved they belonged.

In the years that have followed, Big 12 schools have played in the BCS National Championship Game seven times, as the young league quickly solidified itself as a true power in college football. Now, of course, it is in its swan song, with Nebraska departing for the Big Ten and Colorado for the Pac 10 after this season.

The victory marked the high water mark for Mackovic, who was able to enjoy the popularity of “the call” for a short spring and summer. When Brown sprained his ankle in the season opener of 1997 and couldn’t play the next week against UCLA, disaster struck. Texas came apart as the Bruins beat the `Horns, 66-3. Brown never really got well, and neither did his coach. When the Texas season ended at 4-7, Mackovic was removed from the head coaching position and reassigned within the athletics department.

James Brown made a run at arena football and spent some time playing in Europe. In his time at Texas, he had earned a special place.

First, he destroyed the myth that an African-American couldn’t play quarterback at Texas, and second, he had taken “fourth-and-inches,” and made it into a euphoria that will forever rank as one of the greatest moments in the storied history of Longhorn football.

11.21.2010 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Remembering how to win

Nov. 21, 2010

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

It can lead to a deep philosophical and psychological discussion, but the metamorphosis that took place Saturday in the Texas-Florida Atlantic game probably deserves that.

Here was one of the premier college football programs in history, a group that had lost only two games in the previous two years and won at least 10 games for nine straight, seeking to break out of a slump.