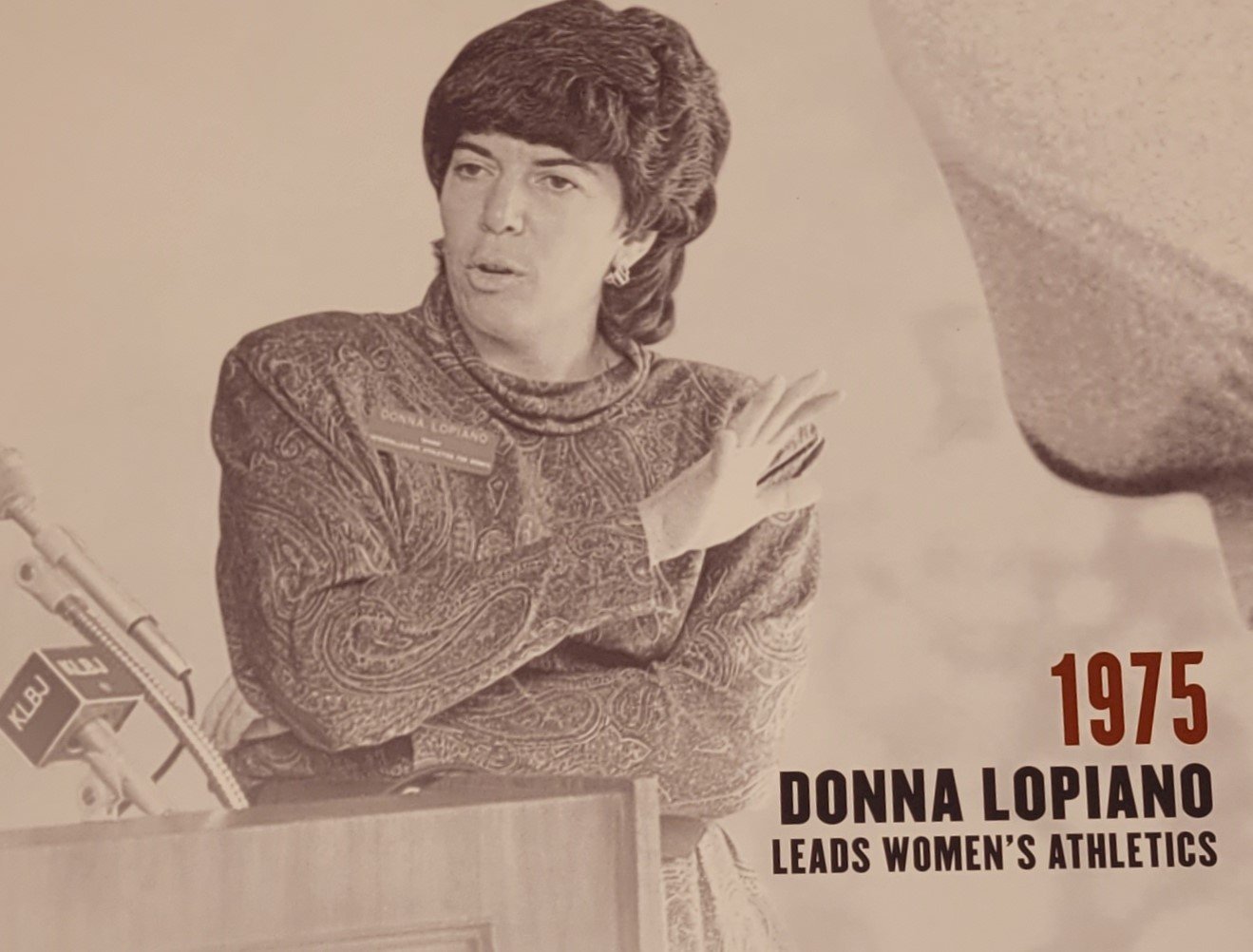

Donna Lopiano

In the book Bleeding Orange by Kirk Bohls and John Maher, there is a quote from Journalist Robert Heard. He says, “The first thing I would do is fire DeLoss Dodds and put Donna Lopiano in there, and she’d take it. She is not from Texas, and neither is DKR, but at least they bleed burnt orange.”

Donna’s oral history, as told through the Eyes of Texas, is at the following link:

Donna Lopiano a Longhorn sports Pioneer

Donna Lopiano pries doors open, whether in Little League baseball, Texas football, the NCAA bureaucracy, or by challenging the stereotype of women’s place in America’s society. Professor and politician Barbara Jordan says, “Her competence is overwhelming. A testament to her success at Texas is the 11 national championships in Longhorn women’s sports by 1987.

Donna made it ok for women to celebrate playing basketball as much as being a ballerina.

Donna Lopiano harnessed women’s sports as a venue to enhance women’s rights in other forums.

Most University administrations are slow to accept change. It took UT 75 years to concede that women could tolerate physical punishment in competitive sports. Tessa Nichols states that in the early years of the 20th century, women’s sports were “circumscribed by gender norms and restrictive ideologies that delineated the acceptable ways women could perform in sports.” During those years, “excessive” competition for a woman was considered too “masculine.” To eliminate the masculine aspect of sports, the physical educators of this period decried record-setting and personal athletic glory. The goal of Women’s sports only “aimed to ensure that the health and educational best interest for their women students were sacrosanct.” Donna Lopiano would prove these clichés as a fraud.

By definition, Pioneers are risk-takers, and without them, there is no beginning. Sports pioneers excel through vision, insight, resolve, and many other intangibles. They can successfully implement new ideas and remove obstacles that others can not. University president Rogers said of Donna, “Texans love go-getters.” Texas women’s track coach Crawford said, “Donna thrives on being a pioneer.”

Pioneers need more time to fulfill a vision than established programs. In addition to dealing with the same problems that all administrators face in athletic departments—small budgets, the ebb and flow of recruiting, and turf wars within the athletic department—sports pioneers are challenged with significant obstacles inherent in changing or creating a new program.

In the early years, men had many challenges as sports pioneers, but women had more barriers. Before a woman could be recognized as an athlete, Athletic Director, or coach, they first had to secure respect and equal rights. At Texas, this was a slow and tedious process that finally took hold in the 1950s. A movement started that would eventually correct many of the biases inculcated into society’s fiber.

1977 – sharing a newspaper article with parents.

Sports led the way in this renaissance, and in 1975, “nothing in moderation,” Donna Lopiano led the charge for equal rights and respect for women both academically and athletically. Lopiano was an “ardent feminist” who fought for women’s rights at a university dominated by a successful men’s program.

Aided by Title IX, the civil rights movement, and her take-no-prisoner leadership style, Donna Lopiano was the right hire at the right time in the history of Longhorn women’s sports.

Lopiano corrected many of the gender inequalities that separated the men’s program from the women’s program, including coaching salaries, dining hall access, and training facilities.

Tessa Nichols’ Master of Arts thesis titled ORGANIZATIONAL VALUES AND WOMEN’S SPORTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS 1918-1992 captures Donna Lopiano’s leadership skills. Tessa says that Donna Lopiano built a successful Longhorn Women’s Athletic Department by establishing:

-

a performance team;

-

student-athlete counseling services;

-

a psychological support system;

-

addressing the health problems of the student-athletes;

-

a commitment to the student-athletes welfare and

-

the creation of the Neighborhood Longhorns.

1975-1992 “Nothing in Moderation” Donna Lopiano makes her feelings known

• “The NCAA is General Motors. And I’m an investor who wants to build a car that doesn’t run on gasoline.”

• “Title IX has never been enforced. It’s the guillotine that’s been rolled out into the city square to scare people off. But it’s rusting and needs a giant can of WD-40.”

1975 – the Master teacher

Betty Thompson, UT’s recreation sports Director, said of hiring Donna Lopiano, “What this program needed was a dynamic, fast-moving, eager person- someone who understood what high-level competition was all about.” However, the President of UT, Lorene Rogers, disagreed with Betty Thompson. President Rogers thought Donna Lopiano’s personality was abrasive, and Rogers was horrified at the very notion that this headstrong individual might work for The University. Rogers commanded Betty Thompson’s committee to intensify its search and find a more demure candidate.

However, Betty Thompson’s committee disagreed with President Rogers’ assessment of Lopiano. The committee stated that Donna’s energy, strong vision, and dynamic intellect convinced them that Lopiano was the right person for the job. President Rogers finally accepted the Advisory Committee on Intercollegiate Athletics for Women’s recommendation to hire Donna Lopiano.

In Italian, donna lo piano means, very roughly, “the quiet lady.” Donna’s friends and coaches knew differently. “I thought I was a passenger in a runaway car for those first few years,” Conradt says. “Donna didn’t understand how laid-back this town was or how much of a threat she was to many.”

The “quiet lady” spent her first year in Austin in Coach Royal’s office, not being silent. She wanted Royal to establish the women’s athletic department as part of the men’s department. Royal rejected the “quiet ladies” overture, so she got louder, and Royal got “deafer.”

Years later, Donna noted that AD Darrell Royal played a vital role in women’s athletics’ thriving financial health. Lopiano said that DKR did the right thing in not being pressured by her to fund both women’s and men’s sports because if he had, “both departments would have gone under.” Of the 296 colleges in the NCAA’s Division I, only nine have autonomous women’s athletic departments, but those nine were six times more likely to have teams in a women’s Top 10 than schools with merged departments.

Sports Illustrated DECEMBER 17, 1990 states PRIMA DONNA WOMEN’S ATHLETIC DIRECTOR DONNA LOPIANO HAS TAKEN THE BULL BY THE HORNS AT TEXAS.

Robert Heard, the publisher of Inside Texas, a newsletter on Longhorn sports, says, “She’s gonna wind up with every scholarship in the program endowed.” It took hustle, but Lopiano collected $3.68 million a year to make her department go. Only slightly more than 10% of the women’s budget comes from revenues generated by the men. “

By focusing on long-term goals, Donna made sure that nothing in the women’s department was secondary to the men’s department.

-

One of her first long-term goals was to hire full-time coaches instead of using teachers who coached on the side. She envisioned coaches as “Master Teachers”. She believed that “athletics was not separate from education, but intimately connected.” The word “Master” referred to the coaches as the very best in the sport they taught, and the word “Teacher” stressed the need for coaches to possess a sound “personal, educational philosophy.” By 1982 all of the Coaches in the Women’s Athletic Department were full-time employees, and each coach was ranked in the top 10 in the country in their respective sports.

She said that in 9 years, only five scholarship athletes left the program due to academics. She also said that only 50% of all freshmen from the general UT population graduate from UT, but 95% of the student-athletes graduated.

-

The second long-term goal was to move the Longhorns from competing only on a regional basis to competing nationally, with a focus on playing at least six nationally ranked-teams every season.

-

The third Long-term goal was to fund the maximum number of scholarships as designated by the organizational rules.

-

The fourth long-term goal was to achieve an “exemplary graduation rate” of at least 95%. (Many parts of Lopiano’s successful student academic model were adopted by the men’s program in 2007.) Lopiano said the coaches she hired knew how to build a winning program with an educational priority.

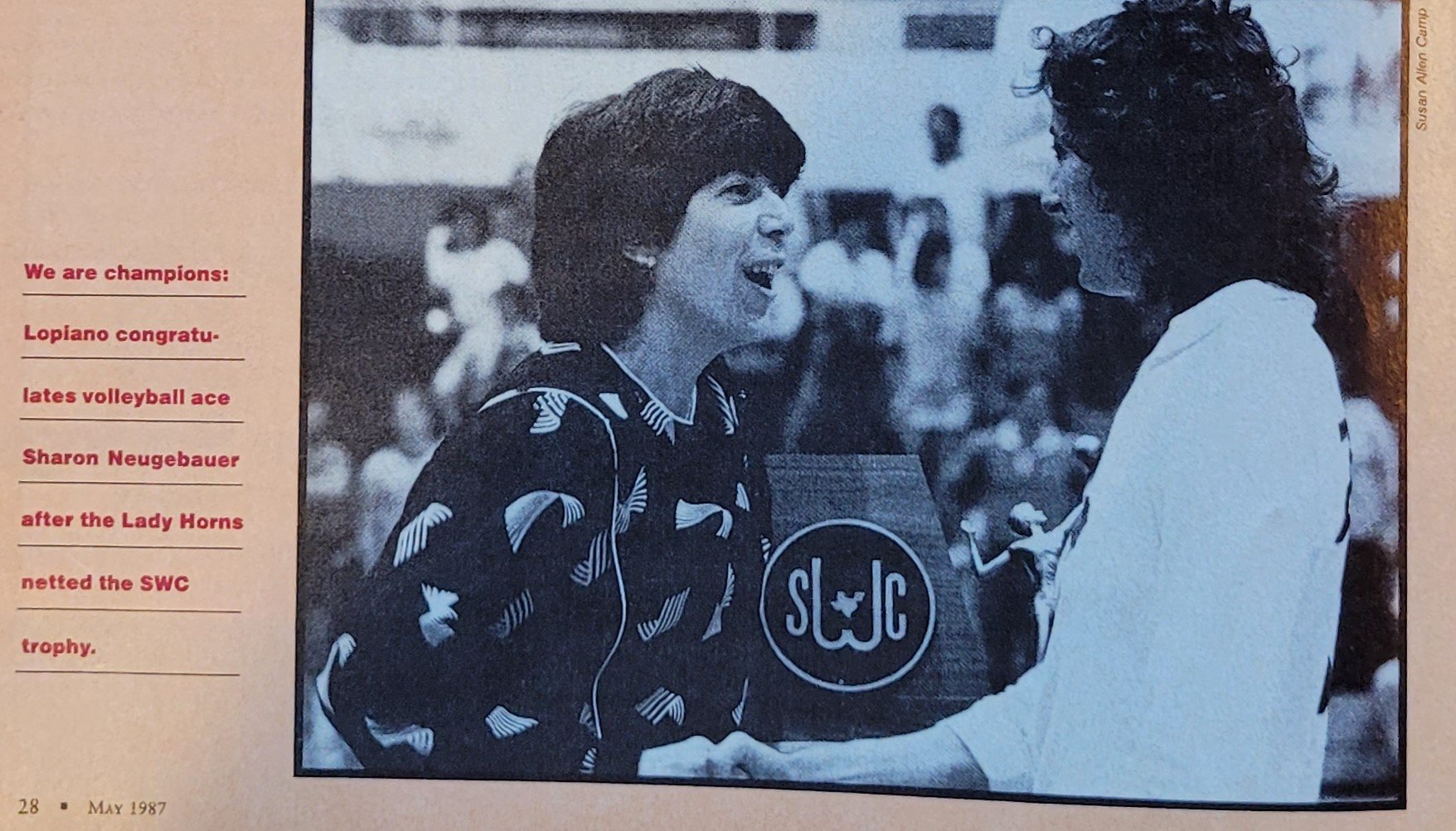

Donna congratulating Volleyball player Sharon Neugebauer

Unlike Anna Hiss, Donna Lopiano believed that a sports organization structure could be created that valued winning, education, and student-athlete welfare. Tessa Nichols states that Lopiano believed she could balance all of these factors and have great athletes and teams. The transformation of her convictions and long-term goals into reality is apparent.

Because of her high standard, Donna went thru 16 coaches in 10 years. “They were my mistakes, every one of them,” she says. “But you can’t live with your mistakes, because you’re destroying kids.”

The NCAA wins the battle against the AIAW and Donna is not happy.

The Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) was founded in 1971 to govern collegiate women’s athletics to administer national championships (see AIAW Champions). The association was one of the biggest advancements for women’s athletics on the collegiate level. Throughout the 1970s, the AIAW grew rapidly in membership and influence, in parallel with the national growth of women’s sports following the enactment of Title IX. The AIAW functioned in the equivalent role for college women’s programs that the NCAA had been doing for men’s programs. Owing to its own success, the AIAW was in a vulnerable position that precipitated conflicts with the NCAA in the early 1980s. Following a one-year overlap in which both organizations staged women’s championships, the AIAW discontinued operation and most member schools continued their women’s athletics programs under the governance of the NCAA.

One of the AIWA’s biggest mistakes was not offering scholarships to athletes. In 1980, the organization realized the mistake and renounced the NO scholarship rule, but that decision was too late. Legal, commercial, and market forces decimated the AIAW membership, and the NCAA became the governing body for all men’s and women’s college sports.

The Longhorn women’s athletic program disagreed with the decision to dismantle the AIAW. Stating the NCAA’s decision to disallow student-athletes in the governance of the organization and “using its financial monopoly in men’s sports to acquire women’s sports” was wrong. UT was concerned that the NCAA was too commercially driven and considered student-athletes as “investment property.” Many felt that women would not get fair representation in the male-dominated NCAA.

Donna Lopiano stated in an interview for the 1983 UT Cactus that discussed the demise of the AIAW. Here are some of her comments in bullet form:

-

“ football spending was an “embarrassment of riches” and that football revenues should be “shared among all the sports.”

-

The switch from the AIAW to the NCAA cost her department $153,000. Donna said her primary objection against the NCAA dealt with stresses of recruiting that coaches did not contend with under the direction of the AIAW.

Donna’s 19 years as the Women’s Athletic Director for Texas is unparalleled in College history.

Texas won national women’s championships in basketball, cross-country, indoor track, outdoor track, swimming, and volleyball. During her tenure, Texas women produced 314 All-Americas and 14 Olympians. (Note: Softball, soccer, and rowing were not NCAA sports during Lopiano’s years as athletic director.)

-

One National Champion, 8 conference champions, and 8 tournament champions in basketball;

-

Six conference champions in golf;

-

Three indoor track national champions, 2 outdoor track national champions, 8 indoor track conference champions, and 7 outdoor champions in track;

-

Eleven conference champions and one national champion in volleyball;

-

Nine national champions and 10 conference champions in swimming;

-

One national champion in cross country;

-

One runner-up to the national championship, one semi-final appearance, and 8 conference champions in Tennis, and a

-

93%+ graduation rate.

Jim Deitrick says of Donna, “I had the pleasure of serving as a faculty representative on the Intercollegiate Athletic Council for Women for four years under Donna’s direction. She was the best! She was determined, strong, bold, outspoken, and brilliant in developing her vision and making it a reality. Times change, but I wish we hadn’t deviated from her core positions. Thanks, Donna!

Below is a slide show of moments in Donna Lopiano’s life.

Donna’s success in fund drives and great coaching hires helps the Women’s program grow

President Lorene Rogers helped the Longhorn women find alternative internal and external sources of funds to support the women’s program. Internal included Auxiliary ventures such as royalties from the sale of Longhorn merchandise and voluntary student athletic fees. External funds came from independent sources which included private donors, The Fast Break Club, scholarship endowments, and gate receipts. Lopiano was proud of UT President Rogers when she said the tower should be lit for Longhorn’s success in women’s athletics.

By 1983 those alternative sources of funds included $500,000 from optional student athletic taxes, $250,000 from gate receipts, program advertisers, $250,000 from the option seating football program, and $850,000 from the interest in the auxiliary enterprise’s account.

In 1966, the Intercollegiate budget was $700. In 1975, it was $128,000, with 28 scholarships available. In 1983, it was $1,000,000, with receipts of $1,850,000. In 1987, the Women’s athletic budget had grown to 2.8 million, and by 1992, it was 4.2 million.

1987-1994 – a walkathon was a primary fund-raising event for the women’s department. In 7 years this event raised $480,000.

Horns UP to a pioneer who overcame many obstacles to create a first-class Women’s sports program at Texas

1993

This year, a battle ensued for more equity between the men’s and women’s sports programs. Over a three-year period, the participation rates and scholarship rates were to drop from 77 percent to 56 percent for men and increase from 23 percent to 44 percent for women. It was ordered that the University generate the money, not men’s athletics.

Donna’s feelings about leaving the SWC

Texas women’s athletic director Donna Lopiano supported joining the Pac-10. Donna says, “I made no bones about it. I think Texas needs to be with more like institutions. I think Texas and A&M have outgrown their compatibility with the other SWC schools. I don’t particularly like the SEC. I don’t like their academic reps and the ability of the schools to control their athletic programs. I like strong president-controlled schools like in the Pac-10 or Big 10.”

One Comment