1963 George Sauer A talented but Conflicted Soul

GEORGE SAUER

George Sauers’s story is about a brash individual who felt he and most of the other professional football players were terribly mistreated. In many ways, he was like Joe Don Looney, a counter-culture icon stuck in an era of conformity—one who left the fame of pro football in search of a deeper meaning of life.

At Texas, Sauer was an under-utilized receiver in Darrell Royal’s run-heavy offense. His father, a former college star for DX Bible at Nebraska and a former Green Bay Packer, happened to be personnel director of the Jets from 1962-69 when clubs in the upstart American Football League were desperate to find the talent they could lure away from the NFL.

The Jets hit the jackpot with the quartet from Texas.

“All of us wound up being better in the pros than we were at Texas” “Lammons said.

Sauer had an extremely productive career. He was chosen to four all-star teams and was a two-time All-Pro.

In a primarily defensive struggle in Super Bowl III, Sauer had eight receptions for 133 yards — more catches and yards than he had for the entire 1963 season at Texas.

The team and Moreland Funeral Home in Westerville confirmed that George Sauer died after a long struggle with Alzheimer’s disease.

In 1970, Sauer walked away from football, turning his back on a sport he called “inhumanly” tal.” In 1972, he penned the introduction” to “Meat on the “Hoof,” a still controversial expose of the brutality of UT football.

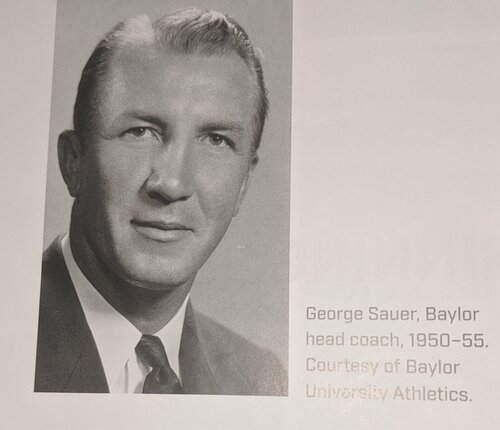

George Sauer’s dad as the head coach at Baylor.

Sauer loved sports, and his first blush with football was as the Baylor Bears’ mascot when his father was the coach.

After Sauer lost his father to Alzheimer’s, he wrote a poem that captured his sorrow and a suspicion that he might suffer the same fate — “an old man dances in my mind his broken brain rattles mine.” Sauer never finished his novel. Alzheimer’s began to take its toll.

“He became something of a hermit,” Peter Lammons said.

Sauer passed away in 2013. According to published reports, no one from his college or pro playing days attended his funeral.

A quote on the Internet sheds a little light on a man who was liked by many but chose to live a lonely life. The quote sums up my understanding of George Sauer, a man I only know through research. Billy Dale

The author’s name is unknown, but in many ways describes George Sauer.

“I became a loner. I became a mountain man. Many of those qualities are very good qualities, and they help you do your work, help you be singular, and keep the artistic integrity of your work intact, but they don’t make it very easy to live your life.”

New York Times- “Longhorn George Sauer walked away from football, turning his back on a sport he called “inhumanly brutal.” The words he used in the whole article were not ambiguous. George told Dave Andersons of the New York Times that “for me, playing pro football got to be like being in jail.” He said, “football does not do what it claims to do…It claims to teach self-discipline and responsibility, which is its most obvious contradiction. There is little real freedom. Instead, the system – the power structure of the coaches and the people who run the game – works to mold you into something they can manipulate.”

George Sauer’s is driven by the voices of the Counter-culture of the 1960s generation.

Starting in the late 1950s, many college campuses across America acted as incubators for a counter-culture revolution. This new breed of students was disillusioned with the status quo, rejected authority, and rebelled against traditional values. By 1967, the Guadalupe “drag” was populated with “flower children” who chose to spread their communal spirit of peace and love while spewing anti-war slogans and anti-authority rhetoric.

The 1960s song written by the Beatles, “All you need is love, love is all you need,” was considered by many as the mantra that would finally create perfection in an imperfect world. For many, It was a song that captured and reconciled all the social, political, and religious upheaval ravaging America’s soul. Many thought that, for once in American history, idealism would triumph over reality.

During this period, George Sauer was a Longhorn football player and New York Jet. He was not a “flower child” but an idealist- a writer and poet with a quixotic personality. It is a dangerous combination where ideals control the individual’s persona, but reality intrudes and disrupts the perfect state. The sport of football and his coaches were the reality intruders.

George Sauer, the Athlete

As a high school athlete, his years were non-descript until his junior year, when he blossomed into a star on the team and a football scholarship to Texas in 1961.

The scholarship offer was pre-ordained. Because of George’s junior pedigree, he received a scholarship offer to Texas the day he was born. His father, George Sauer Sr., was an all-American halfback at Nebraska when D.X. Bible was the head coach, and he was later inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. Professionally, he played for the Green Bay Packers, coached at several locations, and ended his career as the Jets’ director of player personnel. The New York Times says, “When Sauer (George, Jr.) finally decided to go to Texas, his mother showed him the letter they received from Coach Bible all those years before. Coach Bible said, “As for George Jr., don’t worry, I’ve got a uniform reserved for him here (Texas) in 1961.” George Junior said, “It was as though something was driving me from behind to do those things.” Many thought that drive was motivated by his desire to live up to his parent’s expectations.

At Texas, George rejected the people’s perception of him as just another football player. He wanted to be recognized as an intellectual, and intellectuals had to make all A’s in their school course load. Ernie Koy, a teammate of George’s at Texas, said: Billy, The comment about dropping courses because he was going to make less than an ‘A’ happened more than once. He would have to go to summer school to become eligible for the following fall.”

Unfortunately, signing with Texas was the wrong decision for George’s skill set, and from the beginning, George was under-utilized in Darrell Royal’s run-heavy offense. Frustrated with an offense that chose not to pass, George left Texas early to join the New York Jets. His move was unprecedented in college football in the ’60s. He became the first Longhorn to skip a year of eligibility to bolt for a pro contract. Stunned and angry, DKR banned Jet Scouts from U.T. premises.

Comments from George Sauer’s Longhorn roommate

One of my journalism profs at UT said you can’t be more unique than you can be more pregnant. You either are, or you aren’t. Grammar be hanged, I’m going to say George was the MOST unique individual I’ve ever known. We were roommates in 1963, the first national championship team. I guess the coaches thought anyone, but George would be offended to be roomed with a student manager instead of another player. And they would probably be right! George was so crazy he fit right in with all the other non-jocks in our wing of Moore-Hill Hall. He could beat anyone at anything — pitching quarters at a coffee can, flipping playing cards at a hat, throwing shuttlecocks at a tiny basketball goal attached to a wastebasket. His hand and eye coordination were uncanny. We’d have batting practice in the hall with the handle of a golf club and a ping pong ball. Every pitch looked like a Hoyt Wilhelm knuckleball, and most of us batted about .100. George could hit every pitch. Often, right in the middle of one of the games in our room, his personality would change. He’d say, “Alright, everybody out; I’ve got a quiz tomorrow.” As soon as the door closed, he could get out his electric guitar and play for hours. His redshirt year, he and some of the others who weren’t going to be playing in the Cotton Bowl the next day, emboldened by some brew, had a contest to see who could knock a heavy hotel chair the farthest with a forearm shiver. George won, of course, against all the bigger players, but he broke a window — and his forearm in the process—anything to win. The craziest thing he pulled was dressing up like a Catholic priest with a black T-shirt over a white shirt worn backward and a dark sports coat. About six of us — he was the lone jock — went to the all-night Pancake House about 2 a.m. All of a sudden, George jumped up in the middle of the table and yelled for quiet. Then he told the stunned diners he was going to give them a blessing. I’d had two semesters of Latin, just enough to know that all the Latin he was spouting made absolutely no sense. Then he said Amen in English, and the diners echoed his benediction. Several stopped by the table to thank him. It was so hard to keep a straight face. He was truly one of a kind. The fine story about George quotes several of the comments made on George’s obituary on the Ohio funeral home website. One was conspicuous in its omission, however: Signed only “Joe” from Florida, it reads, “George, you were a kind and gentle soul, and the best receiver I ever had.” Wanna bet that’s not Broadway Joe?

Roy Jones

The Jets selected George in the AFL’s redshirt draft in the fall of 1964. Playing for the NFL (not the AFL) was George’s first choice, but he says, “I think the NFL people were certain that I would sign with the Jets (because of my father), so they wouldn’t spend a draft choice on me.” Destiny was smiling at Sauer. He joined the soon-to-be Super Bowl Champion New York Jets.

As a professional football player, Sauer was one of the most feared receivers of his time. He combined an intuitive understanding of football with great hands, fluid movements, and precise routes. Namath said. “Nobody can cover George one on one.” He was selected to the AFL All-Pro team four times. Don Maynard said that George Sauer was a better receiver than he was, and if he had pursued his career until the end, Sauer would have ended up in the Hall of Fame. He was well on his way to becoming a legend when he quit.

Sauer quit after catching passes for nearly 5,000 yards in six seasons with the Jets. Sauer said he left because “I always wanted to do something else.” “I had reached the same point my father had: to be on an NFL championship team.” “I’m not astute enough psychologically to know for sure, but maybe it was about sons wanting to be as good or better than their fathers.” Still, as history unveils, the reasons “reti” from professional football were much more complicated.

The video below shares stories about NYork’sk’s Jet Jim Hudson (2:58- 4:17 mark) and Jim Hudson and George Sauer (8:15- 9:40 mark).

In the prime of his football career, the realities of the sport he played (as he viewed them) led to a disillusioned soul.

He chose to stiff-arm football and implement a scorched earth strategy using the sports media as his megaphone. George needed to escape reality (jail) and return to the comfort zone of Utopia.

Few successful professional people choose to quit their prime jobs to pursue a “worthy” cause. Most understand that business, politics, power, money, and winning are the end game. They may disagree with the system but choose to tolerate the process. Not George– he decided to rebel and tell. He blew a whistle on the human transgressions of football. He said, “The structure of pro football generally works to deny human values’ and he criticized its ‘chauvinistic authority.”

Coach Weeb Ewbank ignored George’s critical public comments about football and said: “He will be missed very much, both as George Sauer, the player and George Sauer, the person.”“ “The fans believed Weeb and the sports world moved forward without George.

George rejected the absolute authority given to institutions, organizations, and individuals to control a player’s destiny. Most athletes internalize these types of frustrations and move on with life. Others cannot or will not. Their suppression of perceived injustice leads to a lifelong bitterness ingrained in their character. I know many players of this ilk.

His plan for self-liberation from football was to write. His first attempt at writing was the foreword to Gary Shaw’s controversial book Meat on the Hoof. Then Life magazine asked him to write a 12,000-word article about quitting pro football. This article and all of his other efforts at writing were never published.

Mark McDonald wrote a book titled Beyond the Big Shootout. One chapter deals with the subject he titles “Wine to Vinegar.” He says, “I played with a number of guys at UTEP who not only regret the time/effort required to compete in college football but there’s more. An equal number blame the system (or the coaches or the University)……. “. They turned bitter.

George Sauer’s Epiphany

Mirror, mirror, on the wall,

Who is the fairest of us all?

According to George, the NFL was stunning and beautiful to the fan base, but that image was incorrect for the NFL/AFL players. For the players, the image was a curved, distorted mirror of hopelessness.

Many agreed with George’s assessment of professional football.

I admired George, followed every bit of his career, was shocked when he left the game and upset that it was impossible to keep up with his “afterlife”. Later, when I read about his feelings and reasons for leaving…it made sense. I was also an art student and my conflicted feelings about violence in sport were confirmed by George’s decision. Watching him play and rooting for him in particular… Gregg May 16, 2013

-

I admire him for taking a stand on player treatment and walking away in his prime. God Bless. Jim May 12, 2013 | OH

-

When hearing of Sauer’s death, Knutson, who still has letters and poems Sauer sent him, wrote a tribute for some closure. “George Sauer was the most interesting guy I’ve ever known,” he wrote. “It always amazed me that, though I had gotten to be such a friend to a Super Bowl hero, I was never awe-struck by it. I think that was because of the depth of the man. The more I came to know him, the more I realized how much more there was to him than just a former football star. He was an incredible man who could never overcome his demons. His is a sad story about a man who, I think, wanted to achieve greatness and, at the same time, was scared to death of the greatness that he wanted to achieve.”

-

There is an Interesting story on the mental state of football players. I once did an interview with Hall of Fame Eagles center Alex Wojciechowicz here in NJ. He told me if he had to do it over, he would not have played in the NFL. He was a member of the Seven Blocks of Granite at Fordham University and played with Vince Lombardi on that team. During our interview, we had to reschedule it because Alex was so overwhelmed by arthritis that he had trouble getting out of bed, all due to his NFL career. In conclusion, he didn’t seem angry at the game, but you could read on his face that he wished he maybe had not played pro football.

Struggling to Write

After completing his football career, he chose to make a living as an author and poet. He wanted to write a novel like Peter Gent’s North Dallas Forty. The New York Times said Gent’s book was a “dark, funny, profane novel … which dramatized the game’s ruthlessly competitive, aggressive elements.

George spent considerable time trying to convert his thoughts about football to paper. Sauer’s always talked about his novel, the project he would work on no matter his day job. Having once been employed as a textbook editor by Simon & Schuster, the New York publishing house, Sauer submitted his partly completed manuscript for consideration, but it was turned down. Tormented and frustrated, Sauer never found the rhythm to complete a novel. The New York Times theorized, “He couldn’t bear the imperfections of his prose, perhaps discovering, as Peter Gent confessed in 2003, “Writing is the only thing I have done that comes close to being as terrifying as being a football player.”

Writing is a challenging profession. Converting surface words into cognitive thoughts that translate into content that a mass audience will want to read is a complicated process. The Times quotes John Dockery saying that Sauer “walked away from money, from everything, because it was too painful for him. Encapsulating that pain into a work of fiction must have been a great challenge. “

“I don’t know what he expected to do with his life other than being a novelist,” said his third wife, Virginia Dugan, 64, who married Sauer in 1979. The marriage lasted a year and a half. “He never saw his life as anything else.”

Keifer said that she believed her brother always intended to be a writer, and her earlier memories of Sauer were of him jotting down his thoughts — “sometimes dark” — on the nearest sheet of paper. His Jets teammates would tease him about his “little black box,” Keifer said. The box was a small container filled with index cards. He would write down words he did not know on the cards to go back and learn them.

One day, his wife glanced at the pages of the legal pads with Sauer’s writing. She found a title, “Never Before Seen Again,” and a protagonist named Aggie Bitters but could not discern a plot or the tale Sauer was attempting to tell.

“It was almost as if he wanted to convince the world that he was an intelligent human being and not just a dumb football jock,” she said. It was also, she said, likely therapeutic.

A snapshot of George in the late 1990s offered by the Associated Press.

Dane Knutson, a friend of George, said: “He had problems I couldn’t solve.”

In the late 1990s, George Sauer Jr. moved to Sioux Falls, S.D. He was employed by the Sunshine Food Stores, stacking shelves by day and writing his novel by night.

Mike Dhaemers, 55, Sauer’s supervisor, said, “George would talk about how he would go home and write, but, you know what, I would never see any of his writing. ” Dhaemers remembers him as friendly, intelligent, and interesting but private. He was so secret that he worked in the store for more than a year before anyone discovered he was a former football player.

Dhaemers said, “He asked for time off to go to New York, and he showed up on the ‘Monday Night Football'” broadcast, commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Jets’ Super Bowl team.

A co-worker, Dane Knutson, 66, had not watched the 30th-anniversary show but had heard about it and approached Sauer after a weekend shift to see if it was true that he had once been a football player. Sauer casually confirmed it and spoke to Knutson about the sport, which is far more favorable terms than he had in the 1970s. Knutson said that the only doubt he still had involved how little players were paid for the physical hits they took when Sauer played.

Knutson soon realized that football was not one of the many subjects that excited Sauer. “He was, without a doubt, the most intelligent and talented man I’ve ever known,” Knutson said. “He knew and understood things from medicine and nuclear physics to classical and popular music, Saturday morning cartoons, and ’50s and ’60s TV sitcoms. He was Curious George in the flesh.”

Sauer told Knutson that he slept in a sleeping bag on his living room floor because of an old football injury. His bedroom was littered with piles of books and magazines, many with yellow sticky notes marking spots that Sauer wanted to re-visit. When Knutson knew him, Sauer was having trouble in his fourth marriage and often seemed “tormented.”

Knutson said, “He always seemed so frustrated that he could never finish anything.” He added, “But one day, he would finish that novel; that would be the one thing he would complete.”

According to his sister and others who knew him, Sauer never did finish the book. In 2002, he moved back to Texas to care for his mother, who was ill. It was then, Keifer said, that the signs of Alzheimer’s, which she had noticed many years earlier, became more prominent. She said Sauer became verbally abusive toward her and her mother and was increasingly introverted. In 2007, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

After his mother died in 2008, Sauer moved into an assisted living facility in Westerville, Ohio, where his sister lived. It was about two years before that move that his novel — years in the making, in a white folder, yellow sticky notes plastered all over it — was last seen. Keifer said that the story she thought George was trying to tell was of a confessional booth, with different characters discussing personal issues.

End of Associated Press article

George Sauer passed away on May 07, 2013. Excerpts from the New York Times remember him.

George and his teammate Jim Hudson passed away with Alzheimer’s. The New York Times said, “It is impossible to know whether football caused it.” Still, their stories are strikingly similar to several of the other former football players who suffered from CTE. These once-vibrant and intelligent men gradually withdrew into themselves and experienced increasing individual and social difficulties.

The article painted George as a man who “sadly, never seemed to be comfortable with life.” “He had a series of failed marriages, an unsteady employment history, and a disdain for the sport that at one time had made him famous.”

The Times says, “There is no doubt that as much as the game made him, it also destroyed him and sensed this even at the time. “His life ended as he feared. The New York Times says, “After Sauer lost his father to Alzheimer he wrote a poem that captured his sorrow and a premonition that he might suffer the same fate — “an old man dances in my mind his broken brain rattles mine.”

End of New York Times Paraphrased article.

REFLECTION POINT BY BILLY DALE

Many who knew him said his obsession with writing resulted in a hermit lifestyle. A lifestyle so isolated that many/most of his college and professional teammates did not know it when he passed away. Many of his teammates say they would have honored him if they had known of his passing. Ernie Koy elaborates:

Billy

“I saw George several times in NY, and he and I returned to the UT campus after our first year of pro ball to finish our degree. But I never saw him again. I was a Board member of the Brazos River Authority, which has its headquarters in Waco. George was there with his Mother. I would call and want to come by and visit, but George always had an excuse for why he could not see me. Then I learned that he had gone to Ohio with his sister after his Mother died.”

“I think we all knew George, but we never really knew George.”

As the author of this article, the thought that George did not have friends in the last days of his life disturbed me.

How could this be? I don’t habitually read obituary guest books, but I made an exception in George Sauer’s case. The Obit guest book is more reflective of George’s life journey. It sheds some inspirational light on the life of a conflicted soul.

· David Kelly said, “I met George while playing tennis at Freedom Park in Charlotte. I spent many sunny, wonderful days talking and playing tennis. He was such a special person, so warm and friendly, accepting of everyone, and extremely intelligent.”. David Kelly May 24, 2013 | Charlotte, NC

· Although George was a star jock and I was not, he was easy to be friends with, and we never ran out of things to talk about on the rides. Good guy. Bill Alexander May 14, 2013 | Austin, TX

· As a Sigma Chi Fraternity brother of George in the early sixties at UT, I remember his calmness, courtesy, friendship, and intelligence. He was a fine football player. My prayers are with all of the family. Ken Carr May 11, 2013

· George was like a big brother to me in my early teens. We played many games of all different sports while he was living in San Francisco & visiting Arizona. He was a big kid at heart….always asking, “Come on, one more game, Matt” I miss ya, George…RIP Matt Jablonka May 12, 2013 | Mesa, AZ

· He was a great football player, but, more importantly, a great friend. And I could talk to him about anything. I will miss him. Chris Nicholas May 11, 2013 | Brooklyn, NY

· George was anything but the typical kind of athlete of the day, being well-read and much more cerebral than most. He was a quiet but well-respected leader with that team. He will be missed. alan Friedman May 10, 2013, | Tucson, AZ

· George was one of our most well-known classmates at Waco High School. He was an incredibly lovely person. I was so saddened to hear this news. Rest in Peace, Waco High Tiger!!!!!

You are receiving catches in Heaven!!! CJPC Carol Copeland May 14, 2013 | Waco, TX

· T lilljedahl July 26, 2013 at 9:25 AM I have posted here before about George. I roomed with Pete lammons at U of Texas.

George was two years ahead of me. There is no question he had extraordinary intellectual abilities. He had thoughts that no other guys had. He was very kind to me, an underclassman that played his position. He also had a Fender electric guitar, and when he cranked it up, he could rattle my dorm room, which was right above him. Before he left for the Jets, he had quite the team to work on his grades.

The story goes that he had made a B in a subject, which, was his first grade, which was lower than an A. Looking back, I think he was in a world of his own.

· My condolences to the family. I played for George in 79 with the Carolina Chargers. He was a legend to me, and I was stunned by his regular-guy persona. He was a great player, person, and coach. Funny and loving life. He will be missed. · Ken Helms May 14, 2013 | Raleigh, NC

· I worked with George during his time in Sioux Falls, and we became good friends. We had many long talks about many things, some of it way over my head because he knew so much about so many things…science, medicine, history, poetry, music, literature….I could go on and on. He is aI’ll always miss him an extremely talented, curious, and intelligent human being,. Goodbye, old friend. Dane Knutson May 13, 2013 | Sioux Falls, SD

· Dana, I’m sure you don’t remember me (it’s only been 50 years!!), but I met you and your parents when I was George’s roommate at UT’s Moore-Hill Hall. I was a student manager for four years and was the head manager of the national championship team. I couldn’t have asked for a better roommate. He was a groomsman at my wedding. I’m sorry I lost track of him several years ago, and I am so sorry to learn of his illness. I lost both parents and both of my wife’s parents to Alzheimer’s, so I understand…Roy Jones II May 15, 2013 | Abilene, TX

· Dana, I remember Georgie so well because he spent a lot of time at our house on MacAethur Drive. I could still hear his voice when he phoned Jim…

Missy, this is Georgie….” I remember how slowly he talked….and walked. He was thinking great thoughts even then. I know he has found peace now. I have sent the article to the NYT to Jim. He will be unfortunate too….. Missy Monnig (Watt) May 13, 2013 | Austin, TX.

05.15.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The odyssey of George Sauer

May 15, 2013

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In the poem “The Road Not Taken,” the writer Robert Frost discusses the options faced by a traveler who comes to a crossroads in life and has to decide which direction to take.

“Two roads diverged in a wood,” wrote Frost. “And I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.”

Welcome to the life story of George Sauer, Jr.

Sauer, who was 69 when he died last week after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease, was a poster child for Frost and his story of choices.

Born the son of a football coach, Sauer was a prototype wide receiver in the early 1960s in college football- at a time when they didn’t have prototype receivers. At 6-2 and 195 pounds, he chose to come to The University of Texas just as the Longhorns were flowering into full blossom in the early era of Darrell Royal’s success.

The game of college football was evolving–at a perfect time, it seemed for George Sauer Jr. The days of players playing both offense and defense were ending, and Sauer’s arrival at Texas with a talented freshman class seemed to indicate a new direction for the run-oriented Texas Longhorns. He was redshirted after his freshman season, sitting out the season of 1962. He was destined it seemed, to be a part of some amazing success at Texas.

Even so, Sauer had trouble cracking the lineup of the talent-laden Longhorns–a power-running winged-T team that admittedly disdained the forward pass. Until, of course, they needed it. In his twilight years, Royal often looked back on his career and mused that despite a reputation for not throwing the football, some of his greatest victories came because of the forward pass.

Sauer first became a part of that scenario in the Cotton Bowl victory over Navy that capped the Longhorns’ unbeaten National Championship season of 1963. While wingback Phil Harris caught two touchdown passes, Sauer had a 21-yard reception that set up the Longhorns’ final score in a 28-6 win.

The next season, the NCAA relaxed its rules on substitutions, allowing platooning when the clock was stopped. That meant more playing time for Sauer, who was clearly more suited as an offensive player. His pass-catching skills were critical in the Longhorns’ come-from-behind victory over Baylor, including catches of 10 and 25 yards on the final drive, which helped preserve what would turn out to be a 10-1 season.

It would be an ironic matchup later that season. However, that would underscore his travels with destiny. A lone, one-point loss to Arkansas had knocked Texas from an unbeaten season and a trip to the Cotton Bowl, but the No. 5 ranked Longhorns were rewarded with a trip to the first-ever prime-time Orange Bowl game against No. 1 Alabama. That is where the entangling alliances got complicated.

Alabama was quarterbacked by all-American Joe Namath, who was in his senior year for Bear Bryant’s Crimson Tide. Earning the quarterback start for Texas was a strong-armed, part-time defensive back named Jim Hudson. The `Horns leading receiver that season, with all of 13 catches, was junior tight end Pete Lammons. In that game in Miami, Texas won, 21-17, and Sauer electrified the crowd with a 69-yard TD pass reception from Hudson.

It was also a time of a dramatically changing landscape in professional football. In 1960, the American Football League had been formed as a fledgling competitor to the established National Football League. While the NFL had a strict policy that frowned upon drafting any college player with eligibility remaining, the AFL had no such standards.

Sauer had just completed his junior season (because of the redshirt year) at Texas and seemed headed to be a part of a 1965 senior class that would feature defensive star Tommy Nobis. But Sauer’s father, George Sauer, Sr., (a former coach at Baylor) was the personnel director for the New York Jets of the American Football League.

Against strong protests from Royal (which included banning AFL scouts from the UT campus), the Jets drafted George Sauer, Jr., and he became the first Longhorn football player to leave early for professional football.

The irony, of course, in the road that Sauer took was that it would unite him on the Jets with Namath and Hudson. Soon to follow would be Lammons and defensive tackle John Elliott, as four former Longhorns became part of a glorious era for the Jets, teaming with Namath for fame on and off the field.

Sauer rode Namath’s arm into history in Super Bowl III, when he had eight catches for 133 yards in the Jets’ 16-7 win over the heavily favored Baltimore Colts of the NFL. Hudson also had a key interception in the game, which was a turning point in pro football as it showed that the AFL could compete with the older, more established NFL, just as the two leagues were on the eve of a merger that had been set for 1970.

By the end of the season of 1970, George Sauer Jr. had played six seasons with the Jets. He had been a four-time league all-star. He played in 84 games and had 309 catches (which still ranks ninth in Jet history) for almost 5,000 yards (ranks sixth) and nearly 30 touchdowns. He had more than 3,000 receiving yards from 1966-68 and had his best year in 1967 when he had an AFL-best 75 catches for 1,189 yards and six touchdowns.

Again, at the divergence of the two paths, Sauer walked away from the game. He was 27 years old and at the peak of his game.

To understand the man, it would be important to understand the times. The late 1960s had been a time of cultural change in America. There were riots, hippies, and a war in Vietnam. Whether George was caught up in that, we will never know. We do know that the son, who had grown up in football all his life, would later say that he was disillusioned with the structure that existed in the game. He left the big city and wrote novels and poetry, and became a textbook graphics specialist.

What is important to understand here is that it is not for us to judge whether George made wrong choices or right choices. It is simply our charge to recognize that he made his choices.

In his passing, yet another victim of an insidious disease at too young an age, we can salute what he did and respect who he was.

It is left to us to understand that in life, we may never know the lot that is ours or the lives we touch with what we choose to do. And it is that which defines the journey–on the road which we take.

horns up!

Loved this article, thank you!

Thank-you for visiting the TLSN Longhorn Sports historical site.

Great article! Thanks so much! As a distant relative of George, I had heard of some stories of his persona but not into so much detail. Thanks again

After George quit football at Texas and was going to the Jets, he moved in to an apartment with me in 1965. We had lived next door to each other in Moore Hill Hall where we became good friends. Other than we were both nerds, we had one big thing in common, music. He played a good lead guitar and I was his rhythm man though I was really a piano player. We even wrote a few songs together; sort of jazz in nature.

I was an engineering major with left brain tendency while Georege was certainly the other way. Maybe that is how we got along so well. We followed each other for about 20 years after school and lost touch. I still think of him.

I lived in Moore Hill for 4 years from 1960-1960. So knew almost everyone of the people on this site. Great times.

Thanks for your comments. I would like to add them to George’s bio as presented by TLSN. I want print anything unless I have permission to do so.

Billy Dale

Do you have a jpeg of you from your colleges days I can use to associate your photo with the comments?