This was not the Game of the Century

The Toilet Bowl as told by David Anderson

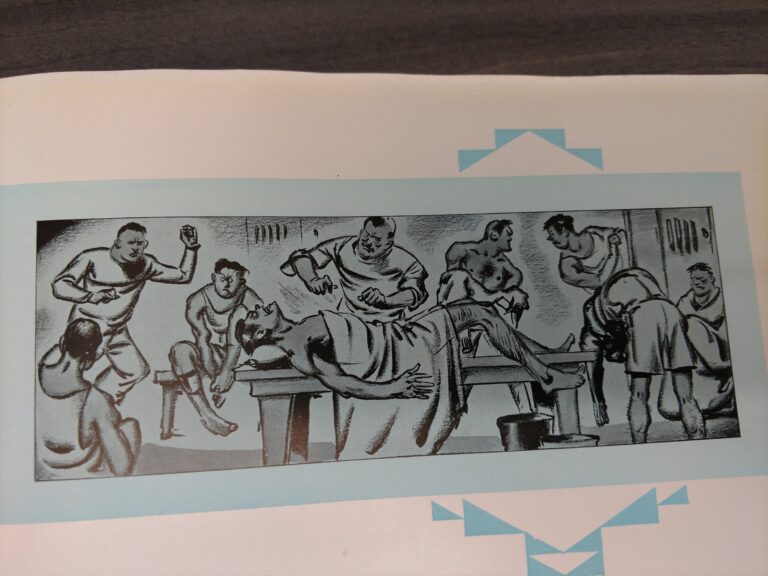

David Anderson says “You may hear about the legendary Toilet Bowl “touch” football game that was played on the Friday afternoon or Saturday morning of the UT-Baylor game. The day it was played was determined by the location of the UT-BU game. In 1971, trainer A. Y. McWright and manager Bubba Simpson were injured, one with a broken wrist and the other with a broken arm. After Coach Royal was informed of the injuries, he came into the managers’ dressing room and informed everyone present at that moment that he didn’t know or care when that “%$@#* toilet bowl” started, all he knew was that it was ended as of that moment. Well, it was ended for at least 364 days!

The Daily Texan Tackles Football, 50 Years Later

BY LARRY UPSHAW IN 40 ACRES, JAN | FEB 2019 ON JANUARY 2, 2019 AT 3:58 PM | 4 COMMENTS

The Typewriter Bowl

The game clock ticked down as the Texas defense faltered and Tennessee’s running back broke for the end zone. We were tied in the bowl game, 6-6. Going for the two-point conversion, the opposing quarterback rolled left, a lineman leading him forward. Only the linebacker on that side could save the day for Texas. As the lineman lunged to block him, the UT linebacker slammed him into the ball carrier and all three crashed to the ground a yard shy of pay dirt.

It’s a goal-line tackle I will always remember, but not because any legendary UT players were involved, nor was a national ranking at stake. I was the linebacker who made that game-saving play at the first annual Typewriter Bowl on a frozen field in Dallas 50 years ago, New Year’s Eve 1968.

The real UT football team was across town preparing to battle the Tennessee Volunteers the next day at the Cotton Bowl. Meanwhile, staffers of the rival student newspapers, The Daily Texan and Tennessee’s The Daily Beacon, clashed in their own gridiron matchup. Those young men who fell in a heap near the goal line to tie the game were better equipped to write about the contest than play in it.

So how did this game between opposing journalism students mushroom into full tackle in helmets and pads, with a sponsor, a trophy, and the blessing of some (very) well-connected people? It started with a budding showman named Bruce Hicks, who was associate news editor in the Texan newsroom, back when the small building now called the Gordon-White Building on 24th Street was known as the J Building. One December evening, a telegram arrived from Tom Gillem, editor of the Daily Beacon.

“We proposed a simple bet,” Gillem says. “It was a coonskin cap against a Stetson, like the governors of states do.”

Hicks alerted Leslie Donovan Banks, BJ ’69, JD ’75, the Texan managing editor, who discussed with other staffers whether to take the bet. Hicks and his fellow news editor, Rick Scott, BJ ’75, had bigger plans. “We’ll one-up them,” he said. “Challenge them to a real football game.”

To raise the stakes, Hicks and Scott penned a dispatch on the wire services, before the Tennesseans had responded, announcing the Typewriter Bowl, a tackle game to be played in conjunction with the Cotton Bowl. They practically dared the Daily Beaconnot to show up. Funny thing is, neither Hicks nor Scott had ever played a down of organized football. Neither considered the logistics of organizing a game like this on a busy holiday. But they were determined to put on a show, and the rest of the staff went along with it.

That year, 1968, was a chaotic one for journalism. Early in the year, CBS news anchor and Longhorn Walter Cronkite, ’35, Life Member, Distinguished Alumnus, deemed the most trusted man in America, reported that we were not winning the war in Vietnam as our military leaders had claimed. After that, President Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not seek reelection. In the ensuing months, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert Kennedy were both assassinated and the Democratic National Convention in Chicago erupted into antiwar protests and a police riot.

The freedom to tell these stories was especially great at student-run, college newspapers like the Texan. Some Austin residents who lived near campus subscribed to the Texan rather than the Austin paper. Staff positions were highly prized and today, the student-elected editor-in-chief is a combination of journalist and campus politician. No matter how media changes, this makes the Texan student property.

After a year as sports editor, I ran for editor-in-chief in spring 1968 until I found out my opponents had unlimited amounts of money to spend on their campaigns. Expenses often included printed literature, yard signs, and payment to people to distribute them. I attended UT on scholarships and barely had coffee money. Neither of the other candidates had held an editing position on the paper, but I saw what I was up against and dropped out of the race in favor of an internship in the Texas Athletics sports information office.

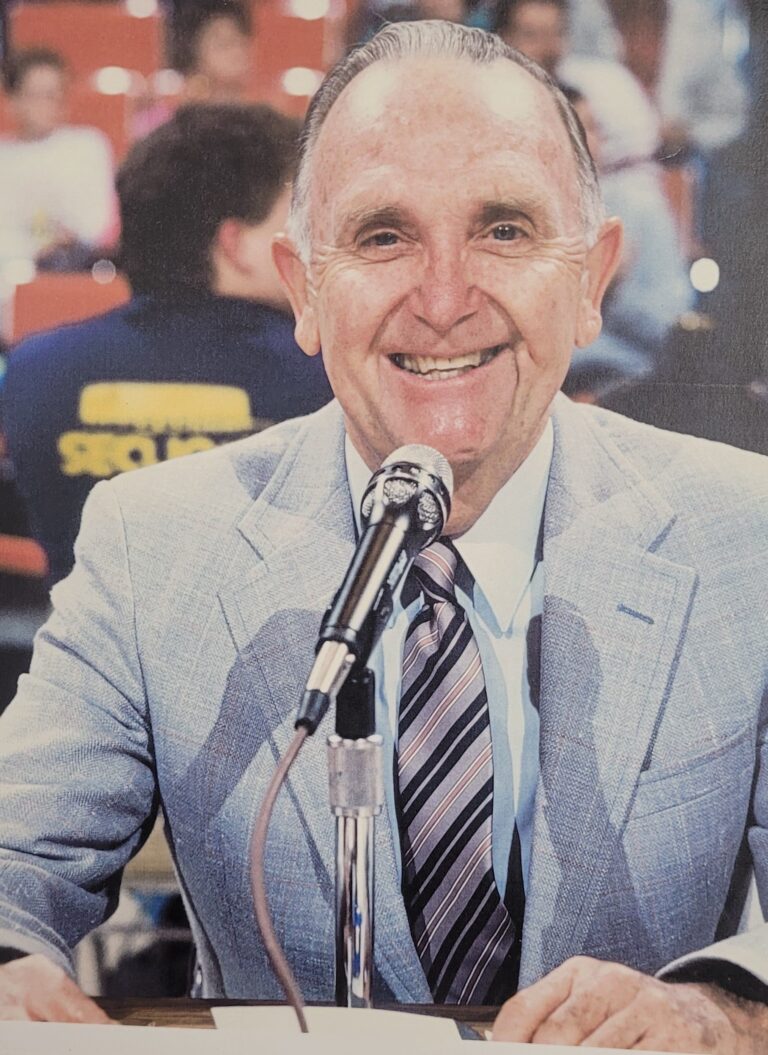

Here, I was around coaches and athletes all the time. How cool would it be for me to end my UT career by suiting up in a Texas football uniform? I convinced my somewhat reluctant boss, Sports Information Director Jones Ramsey, to arrange a meeting for Hicks and Scott with Darrell K Royal.

“We weren’t sure what to ask for,” Hicks recalls. “Coach Royal was amused and asked us if we were crazy or stupid. We admitted to both. I think our enthusiasm impressed him. So he offered to come up with uniforms.”

Scott remembers that Royal assigned student trainer Michael “Spanky” Stephens, BS ’70, to make sure everyone survived the game.

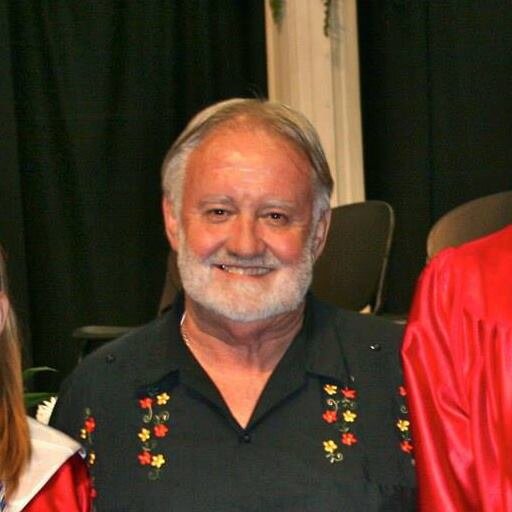

“Coach also strongly recommended that we put an adult in charge,” he says. So we asked assistant journalism professor Griff Singer, BJ ’55, MA ’72, Life Member, to coach us.

Now we had some slightly worn orange-and-white uniforms and an organizational structure to our team. Next, we needed a place to play. Hicks and Scott had already announced the game location, without securing it, of course. They turned to Clint Murchison, then-owner of the Dallas Cowboys. At that time, the runners up in the previous year’s Super Bowl II played home games in the Cotton Bowl. Hicks placed a cold call to the Dallas businessman and somehow got his cooperation, though there were limits to what Murchison could do for our fledgling team.

“We wanted halftime of the Cotton Bowl game,” Hicks says. “Murchison told me, ‘No, it’s either you or the Longhorn Band at halftime. Who do you think’s going to get it?’ I asked what about the day before, and he said that wasn’t possible either because we could damage the field.” So Murchison, acting as our sponsor, arranged for us to use Sprague Field in Dallas’ Oak Cliff neighborhood the morning of New Year’s Eve.

With less than a month to prepare, the Daily Texan Press Stoppers practiced each night at an intramural field off San Jacinto. Some of us had played football in high school, but we were not in game shape. Back in those days, the stereotypical journalism student wasn’t training for athletics—we were intent on emulating crusty news people who smoked, drank too much, and stayed up until we put the paper to bed. That didn’t leave much time for speed and conditioning drills.

In a sign of the times, most of the players smoked. I started out at halfback, but during scrimmages a number of offensive players lit up cigarettes in the huddle. It was like a bonfire. I bugged out for some fresh air playing outside linebacker on defense. During that month, though, we attracted a few serious athletes to the team through word of mouth. Defensive players from the Southwest Texas State (now Texas State) football team drove 60 miles roundtrip from San Marcos to Austin each night for practice. Rumor has it that Tennessee recruited members from its freshman football team. Each team had players you could reasonably classify as ringers.

Leading our offense was Frank Filtsch, BJ ’71, who had been a decent high school quarterback. Behind him was our power, fullback Rick Keeton, BJ ’70, who played freshman football for the Longhorns and then gave it up for campus politics. Keeton was the vice president of the Students’ Association and a bruising runner.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1552581194073_12234 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid { margin-right: -4px; }

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1552581194073_12234 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid-slide .margin-wrapper { margin-right: 4px; margin-bottom: 4px; }

I can assure you that after a half century, your memory of events can play tricks on you. Details you are certain you remember become sketchy. But everyone’s most vivid memory of gameday was the godawful, blue-lipped, hypothermic cold. This was the coldest day of 1968 and the coldest New Year’s Eve in Dallas history by wind chill, which was 4 below zero. The temperature that morning was 16 degrees, with a north wind of 30-plus miles per hour. Players wore thermal underwear, ski masks, and gloves. The few wives, girlfriends and other female spectators who braved the elements were worse off. “Back then, a lady wouldn’t be seen in pants or leggings, no matter how cold it was,” Banks says. “Skirts and pantyhose, that was it!”

In a pre-game scrum of game captains, referees, and coaches at midfield, Singer asked, “Are we really gonna play under these conditions?” We all finally agreed to, but the clock would not stop for anything, not out-of-bounds or incomplete passes. We would get this game over in one hour.

The entire first quarter was our drive for a touchdown, with Keeton up the middle dragging defenders six or seven yards at a clip. Filtsch hit a couple of short passes. Then Moore scampered 35 yards for a 6-0 lead. The two-point conversion failed. The visitors scored a touchdown late in the fourth quarter, then we took the ensuing kickoff down the field but ran out of time at the Tennessee nine-yard line.

The 1969 Cactus acknowledged that our tie game “had proven nothing, except that football was a lot harder than it looked.” Tom Gillem won a coin toss and Banks awarded the visiting team a portable typewriter, sort of a 20th century precursor to the laptop computer. We hated to lose that little typewriter. But the next day, the real Longhorns routed the Vols 36-13, and we all felt better.

Those who participated in the Typewriter Bowl are now in or beyond their 70s. Hicks has forged a career as one of America’s top corporate spokesmen. Filtsch wanders the world as a freelance writer and photographer. Banks is a renowned criminal defense attorney and former Austin judge. Spanky Stephens became head trainer for Texas Athletics and Griff Singer taught journalism at UT before retiring. I’ve written a dozen books on legal and business topics. Other players and Texan alumni are publishers, editors, and philanthropists, and most of them are retired.

There has never been a second annual Typewriter Bowl. Still, it allowed some wannabe jocks to suit up one more time, and gave us a story to tell about an oddball game back in the ’60s. The experience offered some of us a window into our future lives. “I can think of many professional life exercises that have been similar to the Typewriter Bowl,” Hicks says. “Ideas come to you out of the blue and seem impossible to realize, but you find a way to make them work.”

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX