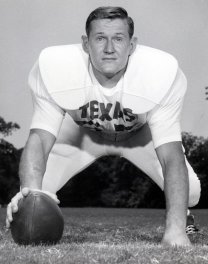

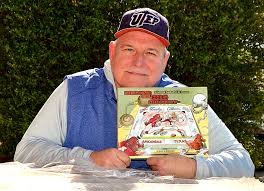

The ’68 Longhorns:Wishbone Dynasty Begins by Larry Carlson

There was a distinct edge to spring football at UT in 1968.

Three years earlier, Darrell Royal and the Longhorns were the toast of college football. Texas won a national title in ’63 and seriously flirted with three other conquests. A magnificent run of 10-1, 9-1-1, 11-0 and 10-1 from ’61-’64 made for forty victories against three losses — by a total of 17 points — and a tie.

But Royal might have been too busy on the banquet circuit after those years, as he would later admit. Perhaps the program got a little flabby and soft.

The results were, for Texas, extremely ugly. Three consecutive 6-4 regular seasons were cause for doubt and despair. Underachieving was for other football programs. Hell, this was UT.

Word was, some folks even wanted DKR gone. Frank Erwin, the bull goose of the Board of Regents, was not a happy man.

There was pressure aplenty. Texas was picked by writers to win the Southwest Conference and tabbed for a top five finish in the polls.

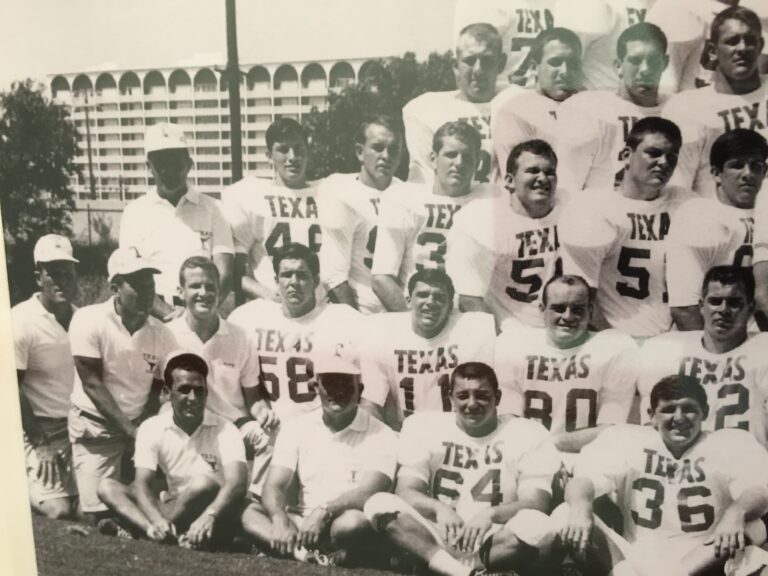

An abundance of talent, layered with veterans and newcomers, peppered the roster.

But there was a new sense of amped up expectations and the spring workouts intensified. Some of the less committed players began a steady drip of dropping out.

Billy Dale, a running back from Odessa, remembers it well. He was a soph-to-be, part of the much heralded recruiting class of ’67 that featured fullback Steve Worster and a cadre of other blue-chip recruits who had been unbeaten as a freshman team. “Every time you came to practice, there was another empty locker,” Dale recalled recently.

All told, close to thirty players surrendered to the rigors of spring and August workouts, though Dale says his high school days that included a state championship as a junior, had prepared him.

“It wasn’t near as hard as Permian’s workouts,” Dale smiled. “I was thinking, wait, this isn’t that bad.”

Most of the players who left were not expected to figure in the two-deeps, though a few potential hosses, linemen Tommy Rohrer and Baxter Braband plus highly touted halfback Pat Sheehan and versatile Deryl Comer elected to jump ship.

Comer’s decision was the one that reportedly buckled DKR’s knees a bit. But the Highland Park youngster reconsidered, came back the next day and went on to All-Southwest Conference recognition as a standout tight end for the Horns.

When word of the attrition spread, Royal told writers that he was confident in the team Texas would field but acknowledged that football was apparently not for everyone.

“I think that if there’s any one prevailing theme in our country, it’s affluence and permissiveness. Youths now have a soft cushion to fall on if they want to and the easy way beckons at every corner,” Royal said, sounding every bit like the seasoned 44-year-old who grew up during the Dust Bowl era in Oklahoma, wearing a damp wash rag on his face at night, to filter the dust and allow sleep. “We’ll tighten the circle,” he vowed.

Aside from the toughening of the team members, Royal decided to grant more autonomy to all his stellar assistants, and officially named Mike Campbell as “head defensive coach.”

Royal was tight-lipped about offensive alterations, allowing however, that he and backfield coach Emory Bellard had been working on featuring three backs — All-American Chris Gilbert, Worster and big Ted Koy — behind quarterback Bill Bradley. Houston writer Mickey Herskowitz would dub the Y-shaped backfield set-up, “the wishbone.”

When opening night’s curtain came up at Memorial Stadium on September 21st, Texas, fourth in the preseason polls, was taken to the wire with eleventh-ranked Houston. It ended in a 20-20 draw.

Gilbert and Cougar RB Paul Gipson starred and the UT ground game was productive. But Bradley did not look comfortable in operating the new formation. And three of his seven passes were intercepted.

A week later on the South Plains, Bradley and the Horns flattened out, trailing Texas Tech 21-0 at half and 28-6 in the third. The Raiders’ Larry Alford had punctured UT’s special teams with an 84-yard punt return touchdown and another long one he took to the two yard-line.

Royal sought to inject some juice into his offense, inserting James Street at QB midway through the third period. The junior hit soph speedster Cotton Speyrer with five passes and looked smoother on the option than Bradley, though he was not as talented a runner.

The Horns closed to 28-22 before falling, 31-22.

Texas hadn’t won since beating Baylor in game eight of ’67.

Royal decided to go with Street as the starter for Oklahoma State.

Bradley, a respected senior captain, was moved to wideout and responded by lightening the mood of his teammates with a self-effacing prank at practice. He loosened the drawstring on his sweatpants before running a route, thereby triggering a flying, full-moon pratfall that provided much needed levity. Royal even called for student support that week in the form of an old-fashioned pep rally. In spite of a tentative start offensively, the Longhorns beat the Cowboys, 31-3, and collectively exhaled before prepping for the annual brawl against OU.

As it turned out, the duel in Big D was the crucial building block that would re-establish Texas on the nation’s football map.

In short, Texas coaches tweaked the wishbone alignment, putting the fullback, Worster, two steps back so as to hit the line later, at less of an angle. The Bridge City soph, already excelling in his first three games, wasn’t the only one to benefit. Suddenly, with Street showing savvy and rapid improvement, the wishbone flashed the potential envisioned in summer.

After a proverbial see-saw battle that afternoon on the Cotton Bowl floor, all working parts clicked when Texas got the ball on its 15, down 20-19, with just 2:37 to play.

Street connected with Comer on three clutch passes, then hit Bradley with another. Worster gashed the Sooners with the last 21 yards on two blasts up the middle and UT won it, 26-20.

Texas had the Bronze Hat, as it was called then, for the tenth time in Royal’s twelfth battle against his alma mater. In post-game comments, Royal gushed about Loyd Wainscott’s defensive work, saying, “He played absolutely the most outstanding game we’ve had a lineman play against Oklahoma.”

Wainscott, the senior from LaMarque, had capable assistance from linebackers Corby Robertson, Glen Halsell and Scott Henderson plus large Leo Brooks at tackle, along with a swarm of white jerseys, all the live long day. The Horns had even found their placekicker, a soph named Happy Feller. In his first start, the Fredericksburg kid hit three field goals, including a school record 53-yarder that broke a 14-all tie in the third.

Not everyone knew it that day, unless it was either Royal or Coach Bellard. But the Frankenstein monster from the wishbone lab had legs now and was on the loose.

No team in the Longhorns’ final seven games would come close to scaring Texas. The offense put up an average of 40 points, with backups getting much of the second half playing time.

The defense, now featuring precocious future stars in junior Tom Campbell along with sophomores Bill Atessis, Fred Steinmark and Bill Zapalac, was doing just fine, thank you. It even got a big boost from Bradley in the last month of the season. Well familiar with the erstwhile QB’s fabled athleticism, the coaching staff moved him from receiver to the defensive backfield. In the regular season finale against A&M, SuperBill stole four A&M passes in foreshadowing his All-Pro status with the Philadelphia Eagles. The Horns led 35-0 by halftime and began turning their attention to their first Cotton Bowl in five long years. Come New Year’s Day, UT embarrassed the Tennesseans who claimed the same initials. The Steers quickly built a 28-zip lead, then cruised in for a cushy 36-13 win that could’ve been worse.

Until the wishbone came along, Royal’s “flip-flop” offense of 1961, featuring scatback James Saxton, set the ground-gaining standard at The Forty Acres, piling up 286 yards rushing per game. The ’68 bunch crunched the numbers to a robust 332 per outing. Gilbert and Worster combined for close to 2,000 yards, with Koy and Street pitching in with almost another 1,000 together. With defenses pinched in run support, Street added 1,100 yards through the air.

The Longhorns had won nine straight games and many observers felt they were the best in the land.

In just a few short months, the wishbone era at Texas had already brought huge dividends. The Longhorns were in business now.

And for future opponents, there was gonna be hell to pay.

(TLSN’s Larry Carlson is a member of the Football Writers Association of America. He teaches sports media at Texas State University and lives in San Antonio.)