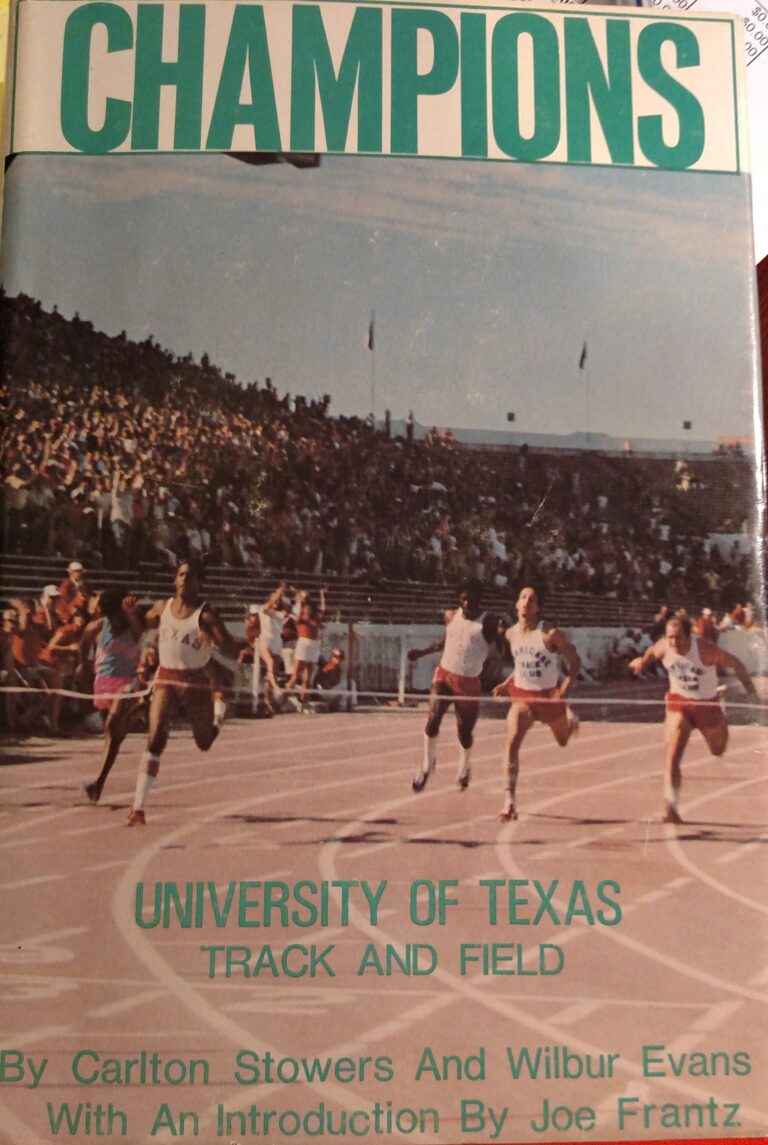

1967 Fosbury Bill Elliott

**Longhorn Track and Field: The Internal Battle to Excel**

The primary goal of track participants is to transform their innate talents, strong discipline, and hard work into peak performance. Track and field require not only physical capabilities but also mental toughness, as athletes must confront personal challenges, flaws, insecurities, and demons. Jesse Owens wisely noted, “The battles that count aren’t the ones for gold medals.” These battles take place internally during practice.

For track participants, the real competition isn’t against fellow athletes; it’s a mental struggle that they face every day. Patti Sue Plumer once said, “Racing teaches us to challenge ourselves. It teaches us to push beyond where we thought we could go. It helps us find out what we are made of.”

The saying “Sports do not build character; they reveal it” perfectly encapsulates the essence of track and field athletes. They encounter “invisible, inevitable battles” and face daily gut checks. Track and field are unique among sports in that athletes reveal their character to spectators as events unfold. During competitions, track athletes mirror the internal struggles that U.T. athletes experience countless times as they write their stories in the history of U.T. Track.

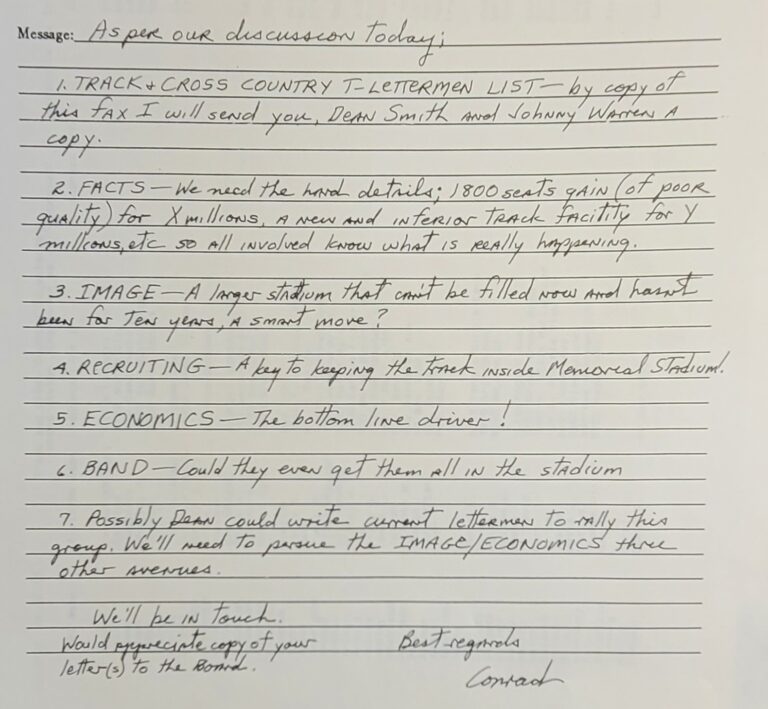

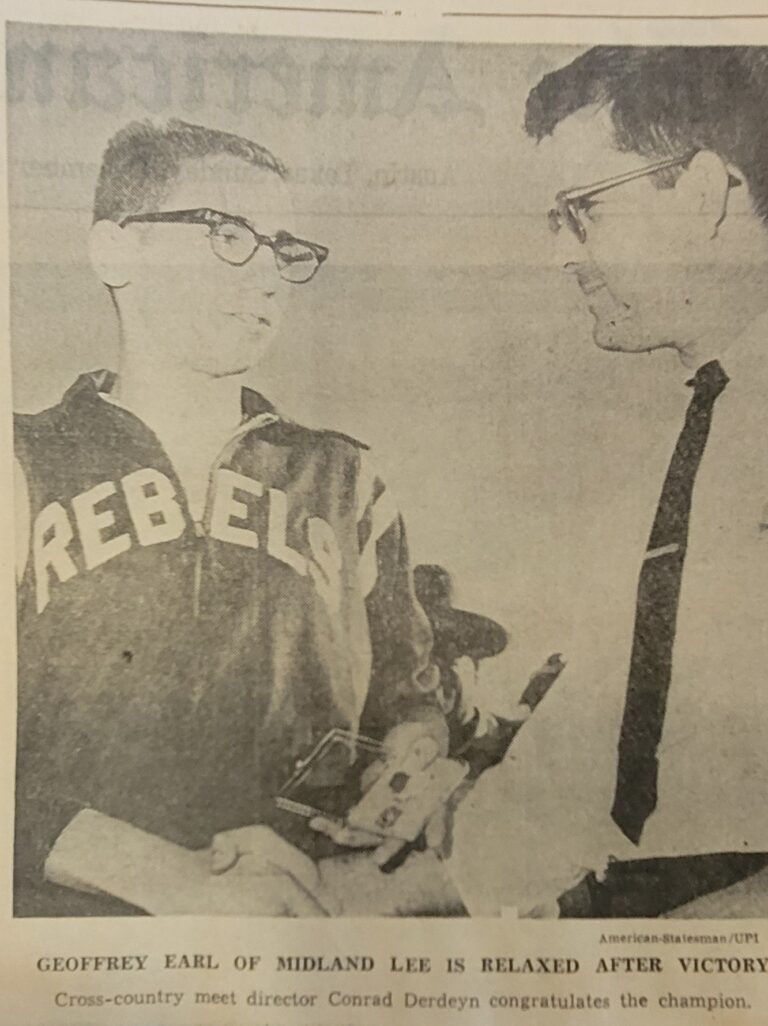

Below are photos that capture the character of these remarkable individuals:

– 1979 Cross Country: Mike Burly

– 1925: Anderson, 6 feet 2 1/2 inches

– 1973 Track: John Lee

– 1968: David Matina

Dick Fosbury – Olympic gold medalist in the high jump

Dick Fosbury didn’t just win a gold medal at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics; he fundamentally altered the way athletes approach one of track and field’s most iconic events. Before him, high jumpers relied on the traditional “straddle” technique, twisting and contorting their bodies to clear the bar. It worked—but it wasn’t revolutionary. That is, until Fosbury turned the high jump on its head with a daring, untested approach: jumping backward.

At first, the “Fosbury Flop” was met with skepticism. Coaches and athletes alike raised eyebrows at his unorthodox style, with its back-first arching leap. But when Fosbury cleared the bar at 2.24 meters (7 feet, 4 1/4 inches) to win the gold, he wasn’t just winning an Olympic title—he was proving that sometimes, breaking tradition is the path to greatness. His victory didn’t just add a new technique to the sport; it redefined it entirely.

The world quickly took notice. The Fosbury Flop became the gold standard in high jumping, and today, athletes still use it to break records. Fosbury’s moment in 1968 wasn’t just a personal achievement—it was a catalyst for change, showing how a single act of innovation could ripple through an entire sport. His triumph wasn’t just about crossing a bar—it was about elevating the entire discipline.

Fosbury developed a curved, J-shaped approach run. This allowed him to increase his speed while the final “curved” steps served to rotate his hips. As his speed increased, so did his elevation. Fosbury made little to no use of his arms at takeoff, failing to “pump” them upwards, keeping them down, close to his body: the next generation of floppers would add an arm pump. Fosbury’s key discovery was adjusting his point of takeoff as the bar was raised. His flight through the air was described as a parabola: as the bar went up in height, he needed more “flight time” so that the top of his arc was achieved as his hips passed over the bar. To increase “flight time,” Fosbury moved his takeoff farther and farther away from the bar (and the pit). Jumpers naturally tend to be drawn closer to the bar, requiring mental discipline to move out rather than in. By way of comparison, classic straddle jumpers plant their take-off foot in the same place every time, less than one foot away from a line parallel to the bar. Photographs of Fosbury attempting heights above 7 feet (2.1 m) show him taking off nearly 4 feet (1.2 m) out from the bar.

Bill Elliott’s Fosbury

High jumper Bill Elliott used innovative processes and techniques to accomplish multiple tasks in new ways. But first, he had to change his mindset and remove mental roadblocks to master the Fosbury.

One of the first disciples of Dick Fosbury was Longhorn Bill Elliott.

Bill Elliott understood that a record high jump required a disciplined technique of building a jump one step at a time. Bill ignored old-school practices and beliefs of high jumping techniques to set high standards for the Longhorns. Elliott won the “head” game and transformed the sense of what’s possible in the high jump.

In late 2019, Glen Sefcik sent the following comments from Owen Yarborough about Bill Elliott.

Bill Elliott is currently going through some medical issues—several months ago, Bill had a bleeding episode, and the cause was a diverticula problem—a pocket led to a severe bleed just before he was scheduled to get his other hip replaced—his hemoglobin count got way done and postponed the surgery —about November 4 he woke with severe stomach pain and the doctors determined he had a bad infection in a pocket this time—-he was at seton hospital for a little over three weeks and was sent to Centex rehab about a week ago…his strength is slowly coming back, but it is and has been a struggle…Bill is a great friend to all of us, and I’m sure he would appreciate your prayers for his recovery…..thanks, Owen Y (Owen Yarborough) from Glen Sefcik.

The prayers for Bill’s recovery worked. In 2022, he has returned to good health with a smiling spirit.

https://fb.watch/dENxh9h2Sn/ (outlook.com) The History of High Jumping

https://youtu.be/9SlVLyNixqU Fosbury flop Changing a mental process is necessary to develop a winning culture.

https://youtu.be/CZsH46Ek2ao Fosbury flop