Campus 1969

Click on the Text denoted in red font on the side bar to visit other sites in this grid

U. T. building in 1898’s

UTNews

The University of Texas at Austin

-

My All American Campus — UT in 1969 By Chad Schneider | Oct. 15, 2015

Aerial spread from the 1969 Cactus. 1969 Cactus Yearbook

The year 1969 brought a tumultuous decade in American history to a close, capturing a place in our collective memory and, for those of us who weren’t there, in our imaginations.

Texas football fans reveled in the thrill of a National Championship, tempered by news of a cancer diagnosis for gritty fan-favorite Freddie Steinmark just weeks earlier.

Man walked on the moon and the Civil Rights movement continued its long march toward justice in the wake of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Vietnam War raged overseas, as did the protest movement against it back in the states. On the coasts, Woodstock and Altamont epitomized the contradictions of a baby-boomer generation that would soon evolve from hippies to yuppies.

[On Nov. 19, 1969, Longhorn Legend Alan Bean became the fourth man to walk on the moon.]

In Austin, the bones of the city we see today were becoming more visible through infrastructure expansion and commercial development projects.

Austin from above in 1969 Douglass, Neal. Austin Aerials – Downtown, Capitol, Photograph, January 1, 1969; http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth33281/ University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library, Austin, Texas.

The UT campus was physically expanding, too, as new buildings began to rise along the East Mall and beyond, including construction of the LBJ Presidential Library and upgrades to Texas Memorial Stadium.

LBJ Library

Coach Royal talks about renovations coming to Memorial Stadium in 1969. Texas Archive of the Moving Image

http://bit.ly/1eODllx

<iframe src=’http://texasarchive.org/library/index.php?action=ajax&rs=GLIFOSEmbedded&w=480&h=360&c=2011_03733&s=embedded&p=video1&b=0′ frameBorder=’0′ style=’max-width:100%;width:495px;height:385px;border:0px;’ width=’495′ height=’385px’ allowTransparency=’true’> </iframe>

While the specter of an unthinkable tragedy three years before still loomed in the memories of upperclassmen in 1969, the daily rhythm of a busy campus carried on, punctuated by student protests and school spirit rallies.

1969 Cactus

And then there was football.

Link to Arkansas-Texas Longhorn locker room with President Nixon 1969

Freddie Steinmark on crutches giving the Hook ’em sign. Dolph Briscoe Center for American History di_05224

The most bittersweet football memories from 1969 are being rekindled by the feature film My All American, which opens nationwide on Nov. 13. The movie tells the tale of Freddie Steinmark, the inspirational heart and soul of the Longhorns 1969 National Championship football team.

After leaving the “Game of the Century” against Arkansas with an injured leg, Steinmark learned that the injury was due to a tumor in his left thigh bone. Though his leg was amputated within days of the diagnosis, Steinmark vowed to be on the sidelines of the Longhorns National Championship Cotton Bowl game three weeks later. Sure enough, he made the trip and received the game ball from Coach Darrell K Royal.

http://bit.ly/1MzOeSb

The following year Steinmark coached freshman football at UT, was a spokesperson for the American Cancer Society and gave motivational speeches across the country. On June 6, 1971, Freddie Steinmark passed away, leaving behind a legacy of inspiration and courage in the face of adversity.

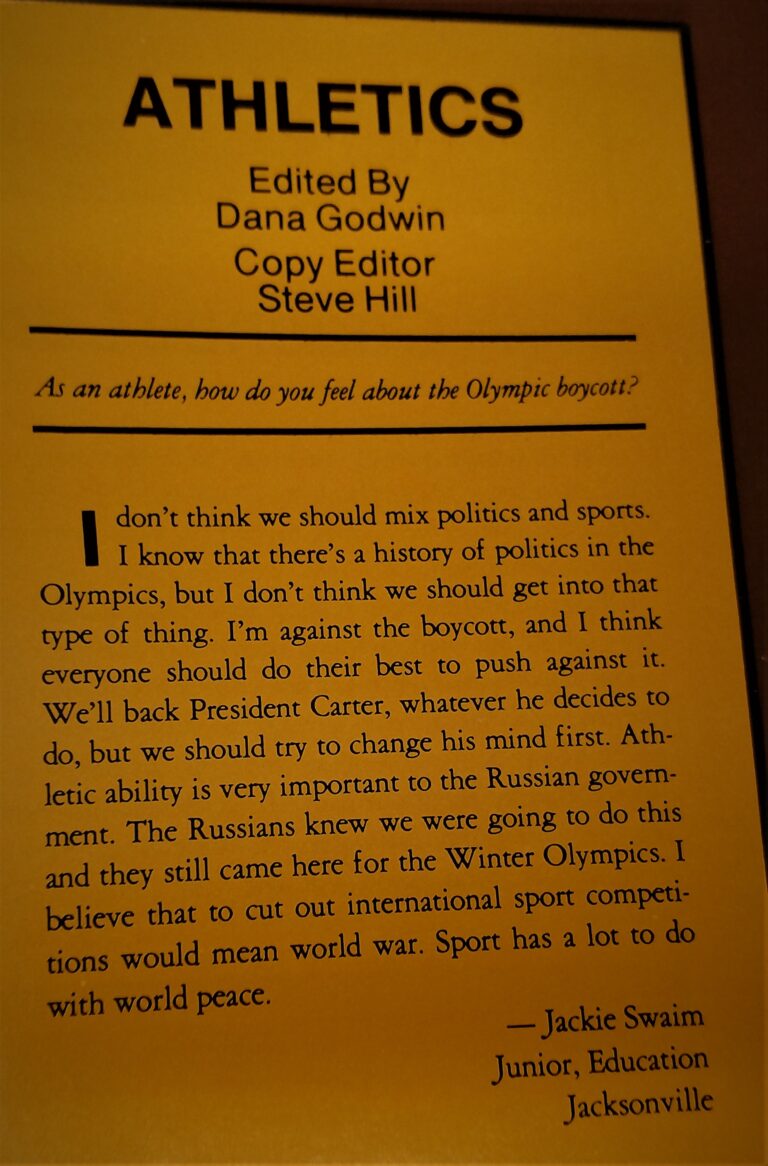

Culpepper’s Commentary

September 30, 2013 by Pat Culpepper

James Street had a heart attack and that’s the only thing that ever beat him. His enthusiasm, his smile, and his love for his sons overacame all obstacles. His teammates loved his spirit and gathered around him like the huddles he commanded during the 1968-69 seasons.

When we had lunch with coach (Darrell) Royal, James would always sit next to coach and get him to smile. He was like Royal – not tall, not blessed with all the talent – but overcame anything. Royal had to be the dustbowl and lack of love from anyone except grandma Harmon in Hollis, OK. Street’s home was in Longview, TX and his father thought he should make it in baseball. If Emory Bellard had not been invited on Royal’s staff and come up with the Wishbone, Street might not have ever gotten under center. Gone are the days of the huddle for many teams, and Street was the master of leadership skills. He had energy, guts, and was a fighter. The play-calls for the Wishbone were simple. “Liz (rip) 22 dive, on two.” Not near the complexity of today’s sideline, signal-waving coaches, shouting directions to the QB in shotgun. This allowed Street to call out his teammates. “McCoy (Bob), get your block,” was the kind of stuff Street would instruct. We will all miss him and can’t forget his plays in Fayetteville in the “big shootout” that gave the Longhorns a chance at the National Championship. Everybody that loved football was watching as Street brought the ‘Horns back against all odds, with his passing, running, and leadership. His name is on the DKR-Memorial Stadium as it should be, next to Bobby Layne, Vince Young, and Colt McCoy. I will miss him. Thanks, James. For what you gave all of us who played at Texas.

© The University of Texas at Austin 2015