Strength , Conditioning, and Rehab

To add depth to the History And Evolution Of Conditioning And Weight Lifting for the Longhorns, some content and photos from the Stark Center site are used on the TLSN site.

One of the Stark Centers’s directives is to study Kinesiology’s effect on athletes and sports. If you want more information about the Stark Center, Please visit the Stark Center at 403 East 23rd Street North End Zone, Suite 5.700 Austin, TX 78712. their Phone # is 512-471-4890, or you can visit their site at

1895

UT hires Frank “Little” Crawford who played under Yale’s legendary football coach Walter Camp. At Texas, Crawford incorporates several forms of physical conditioning along with the standard passing and blocking plays in his workouts. Crawford’s fitness program works. The Longhorns finish 5-0 winning their games by a combined score of 88-0. It is the only perfect season (no losses and no opposing team scores) in the history of Texas football. In an era when physical educators considered running as potentially dangerous for the heart, Crawford’s team jogged a mile to and from practices at Hyde Park. Camp also was an innovator and a football rule maker.

At Texas, Crawford introduced what was then referred to as the Yale System and incorporated several forms of physical conditioning along with the standard passing and blocking plays in his workouts. There are not any records suggesting Crawford’s team participated in any weight work at this time, but it is logical to assume that Crawford used his mentor at Yale, Walter Camps’s system of bodyweight calisthenics, called the Daily Dozen, to condition the Longhorns.

1919 – 1967 Roy McClean slowly and methodically proves that athletes who lift weights add strength, quickness, and speed.

SEE link https://www.texaslsn.org/the-precusors-to-longhorn-strength-coaches

Roy McClean, Lutcher Stark, and Theo Bellmont are convinced that weightlifting can enhance athletes’ skills. McLean uses the techniques suggested in the Milo weight training program to add thirty pounds of muscle to his thin frame, and Lutcher Stark uses barbells to drop his weight from 220 pounds of fat to 180 pounds of muscle.

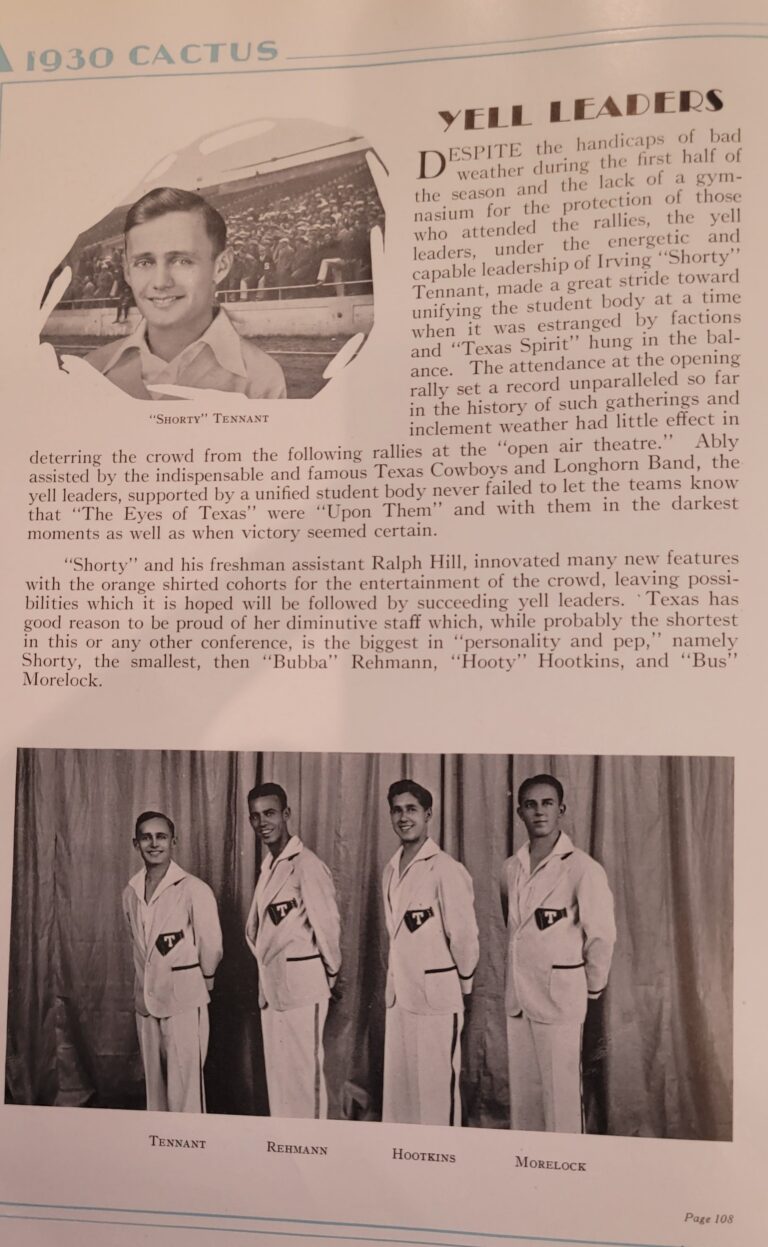

With two Milo barbells and some dumbbells, in 1919, McLean starts the first class in weight training. His focus breaks all the traditional rules of practice. Most coaches still believed that lifting weight made athletes muscle-bound, but they were proven wrong. The eleven male students in McLean’s class had more muscle mass and could jump higher and run faster than before. The popularity of weight training arrives at UT, leading to more classes and more Milo barbells. By 1929 demand for weightlifting classes are so high that a weight room was added to Gregory Gym. When McLean retired in 1967, the men’s physical training program had 660-plus students enrolled in 22 classes.

Most UT coaches up until 1973 chose not to have their athlete’s weight lifting. It was considered detrimental and dangerous to the athletes. After OU decimated the Horns in 1973, the Longhorns asked why, and Jay Arnold answered the question. “We were part of the ‘old school’ when it came to physical and strength training.” “We would lift and condition in the spring and off-season but put the weights away during the season. Oklahoma chose weight lifting all year long. We changed after that game and never looked back. We were in an era of enlightened transition as far as that was concerned.”

Roy J. McLean, born in Austin in 1897, grew up on the edge of the campus and was a “mascot” for the UT football and baseball teams from 1906-to 1911. McLean entered the University of Texas in the fall of 1913 at age 16. In his first semester in the afternoons, he had only one class, Physical Training. That class met at the University YMCA building on Guadalupe, where Mclean began spending most of his free time and met the newly-named athletic director L. Theo Bellmont. In March of 1914, was hired by Bellmont and set up the first accounting system for the Athletic Department. Roy McClean managed the ticket sales for the home football games.

Later that same month, Bellmont introduced McLean to H.J. Lutcher Stark, who’d been the manager of the 1910 football team and would later serve for 24 years on the Board of Regents. (For more on Lutcher Stark, click here). Lutcher told Bellmont about his trip to Philadelphia to learn how to lift weights and eat properly from Alan Calvert, owner of the Milo Barbell Company and the publisher of Strength magazine. McLean said, “Lutcher had dropped by for a visit and to work out with his barbells which he always carried in his car, and which he said had changed him from a 220-pound fat boy into a 180-pound muscular athlete.” At that moment McLean was hooked understanding that sets and repetitions built muscle. Following that visit, McLean and Bellmont continued training and Mclean eventually added thirty pounds of muscle to his lanky frame and became a true believer in the benefits of weight training.

This photo is part of an article that Roy McLean authored in Strength and Health that gives a brief glimpse into the early days of strength training at the University of Texas in the 1960s.

Click here to view the extended file

After the war ended, McLean returned to UT to work on a Master’s Degree and was offered a teaching and coaching position by Bellmont, in 1920 even though he would not finish his degree until 1923. As coach of the wrestling and the cross-country teams, he incorporated weight training and other conditioning techniques.

Ralph Hammond

Mclean was a great success as a coach. He helped wrestling star Ralph Hammond earn a spot on the 1928 Olympic team and his Longhorns won many conference championships. In cross country, Mclean remained head coach until 1933 when it was decided that Clyde Littlefield would step down as head football coach and take over all track and field teams.

By this time, however, Mclean had found his true calling in the weight room. In 1919 when he began teaching at UT, Mclean requested permission to schedule a class in weight training. The two Milo barbells and several pairs of 10- and 15-pound dumbbells owned by Mclean and Bellmont comprised the equipment for that first class, and the training sessions were held in the wrestling room, in one of the abandoned military barracks on campus. In that first class, McLean had 11 freshmen and none of them had ever seen a barbell before. The other coaches, according to Mclean, forbade their athletes to even touch a weight—and told them it would make them muscle-bound. The eleven male students, however, loved the class, and after McLean tested them at the end of the semester and showed them that they could jump higher, run faster, and had more muscle on their bodies, they spread the word to other students and there were soon more young men wanting to take his weight training class than he could handle. And so, additional courses were added, and more Milo barbells were shipped down from Philadelphia.

By 1929 when Gregory Gym was built to house the men’s Physical Training Program, demand was so great that a special weight room was added to the new building to accommodate what had then grown to ten classes per semester. Over the next five decades, interest in weight training continued to grow and in 1967, when Mclean finally retired as an Associate Professor, the men’s physical training program was offering 22 sections of weight training each semester. With 25-30 students approximately in each section, this means that over the course of his long and profitable life, Roy J. McLean taught tens of thousands of Longhorn men how to lift weights.

Frank Medina 1945-1977

In 1945, the University of Texas hired its first full-time athletic trainer, Nebraska native Frank Medina. The 4’10” Medina would remain in charge of athletic training at Texas for the next 32 years, and he was against the idea of heavyweight training for sport up to his retirement in 1977. As he told Terry Todd, “We never used weights in my early days here because the coaches just didn’t want to. And neither did any other coaches in the country,” he explained. “The coaches here all wanted their players to be quick. And I didn’t believe in it either. I still don’t believe in all that heavy stuff. I always said that if God wanted a boy to be bulgy, He’d have made him bulgy…Some of the football players these days look like weightlifters. That’s not good.”

Although Medina did not recommend heavy lifting, he did finally agree that high repetition work with light dumbbells could be useful. He was inspired by a film he saw about Northwestern University’s training program in the early 1950s and then told Todd, “A pair of 20 or 25-pound dumbbells is enough for anybody, no matter how big and strong he is,” Medina said. “You need to see how many times a man can lift a lightweight, not how much a man can lift once or twice.”

As he told Todd, “After we watched the Northwestern film, one of the things we did before spring training was to have the men wear ankle weights and waist weights and weight vests and lift the dumbbells over their heads while they were jogging around in a heated locker room. I worked them hard.”

Heisman Trophy winner Earl Campbell suffered through similarly innervating workouts in the summer of 1977 after new football coach Fred Akers told him to lose 20 pounds before the start of the season. Over that summer, Campbell’s website reports, “Earl met Medina at 6:30 AM, pounding the heavy bag in a rubber sweat suit, running track for an hour, lifting weights and doing 400 sit-ups while wearing a weighted vest. Then it was off to the sauna for over a half-hour. He would attend his classes for a few hours and then participate in practice for the remainder of the evening.” (To read more from Earl Campbell’s website, click here)

Although never an advocate for heavy lifting, Medina played an important role in professionalizing the conditioning program for athletes. In addition to starting the first off-season workouts at UT, he also introduced true physical therapy procedures to the UT athletic department. He also brought distinction to the university by serving on two Olympic teams, and he worked with athletes from a wide variety of sports. He passed away in 1989. For more about Frank Medina visit

https://www.texaslsn.org/frank-medina-1

Early 1960’s Dr. Stan Burnham

Dr. Stan Burnham was one of the first Exercise Physiologists at Texas and our first Sports Medicine Director.

Charlie Cravens

Although he never formally held the title, Charles (Charlie) Craven was, in a very real sense, the University of Texas’ first strength coach. It was through comics that he was first exposed to weight training. Craven was intrigued by the Charles Atlas ads on the back of the comics he read, and as he recalls, he sent away for the Charles Atlas course.

“Cost me a couple of dollars . . . I thought that it would really be neat, I wanted to get a little bigger and stronger and faster, and that was the only vehicle,” said Craven. Once he arrived at UT, Craven began lifting with a friend who owned a set of weights and he began reading about strength and physiology.

During his senior year, Craven began assisting Dr. Stan Burnham, a faculty member interested in athletic training, with some conditioning work for the baseball team. Burnham had been approached by Bibb Faulk, the head baseball coach, for advice on how he could make his men hit the ball farther. As Craven recalls, the program Burnham designed primarily consisted of exercises with wrist weights, ankle weights, and weight vests with minimal rest between sets in the hot gym in the basement of Gregory Gym. Compared to modern sport-specific training, it probably was not the best method to build hitting power. However, it was resistance exercise, and according to Craven, it was his work with those baseball players and Stan Burnham that convinced him he should attend graduate school.

Charlie Craven discusses how he became interested in weight training.

As a graduate student, Craven taught activity classes for the Men’s Physical Training Program, and in the afternoons he assisted the athletic department in establishing a rudimentary strength training program for a few of their athletes. During class days, Craven recalls that he would back his pickup truck into the alley behind Gregory Gym and then, “ I would get some bars and some weights, transport them to the stadium, unload them, let the athletes use them, and then bring them back for the next day of physical education classes.”

After finishing his master’s, Craven taught at Del Valle High School for a year and then returned to UT as a full-time instructor for the Men’s Physical Training Program in 1964. According to Craven, both Burnham and head football coach Darrell Royal asked him to help with weight training for the football team.

Charlie Craven talks about the start of the new weight training new era at the University of Texas.

*Video created using iMovie software

By this time Royal had recognized that in order to compete, the Longhorns would have to become more serious about strength work. Beginning as a volunteer, and later as a part-time employee of the athletic department, Craven became the de-facto strength coach for all men’s athletics in the mid-1960s.

“I worked with football, worked with basketball,” said Craven. “We did a lot of weight vest programs, jump and reach, and of course we had baseball, continuing on, through the last of the Bibb Falk era, into the Cliff Gustafson era.” According to Craven, it took about 12 years before UT coaches came to understand just how beneficial training would be for their athletes. “ . . . Coaches were very fearful because these youngsters were going to become muscle-bound,” said Craven. “A lot of these coaches didn’t want them lifting weights at all.”

Even Coach Royal, Craven claimed, did not embrace the program at first. He told Craven, “OK. We’re going to keep the training program, but I don’t want them to work too much, get too ‘taut’, get too big.” “Now, some of the coaches didn’t like that idea, but Coach Royal liked the idea,” said Craven. “He liked something new, but he wasn’t ready to embrace it fully, and I think that process took him to the mid to late ’60s.”

During these early years, Craven borrowed weight training equipment from the Physical Training Program to use with his varsity athletes. “We started with Elmer’s weights out of West Texas,” recalls Craven. “Elmer had wrist weights and ankle weights. We had weight vests and so forth.” From there, Craven explained, they began using Universal Gyms that had been discarded by the Department of Physical Training for Men. When the physical education department would wear out a universal gym, the athletic department would say, “Hey, we can use this.” Finally, the Athletic Department decided to dedicate some of its own space to a weight room. Underneath the football stadium, up the ramp on the south end of the stadium was a large room numbered DL8. It had formerly been an athletic dormitory and was filled with old Army bunks, with no heat or air conditioning except for a couple of space heaters, that had been used to house recruits who came for campus visits in earlier years. According to Craven, as the physical education department’s Universal machines broke down, “I’d make a deal for it, and we would take it down there, refurbish it, put it up, and we ended up with four of those, in that room. I was able to supplement that with a few other stations and that was where we began.

During most of the 1960s, the programs used by the football teams at Texas were primarily circuit programs in which “an athlete would work as hard as he could for thirty seconds, and then had fifteen seconds to change to the next station and go as many as he could for another thirty seconds.” In the off-season, Craven explained, this created some real challenges for him as he would have all the offensive players for one hour and then all the defensive players for one hour.

Charlie Craven talks about the circuit training workouts he leads during the early years of strength training at UT.

*Video created using iMovie software

Said Craven, “That became a little bit of a management issue because we had, roughly, 70 offensive and 70 defensive players. Because of this, I had to have 70 stations of some sort set up. I would blow the whistle, take on all of these characters and make sure that once they got to a certain spot that they didn’t slip off into the restroom and hide out for two stations.” Craven admits it was a nightmare to try and supervise a workout like that with only one coach in the weight room, “But, we survived well and won a couple of national championships with that process.”

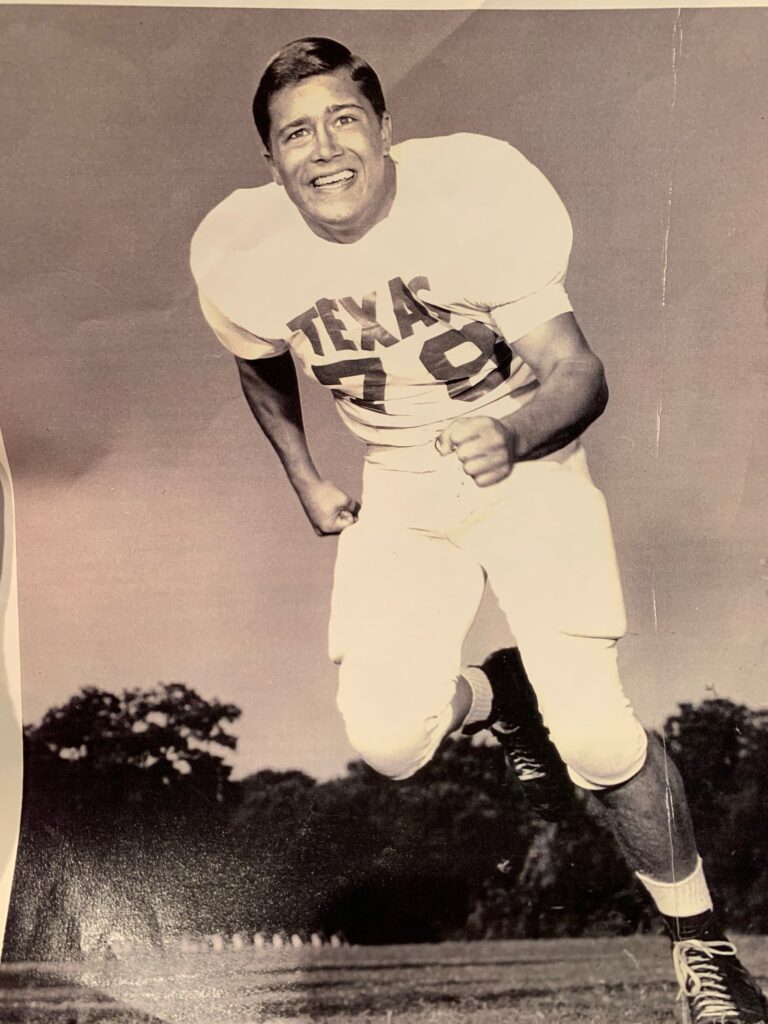

One player who made a big difference in the acceptance of weight training by both coaches and other players was Tommy Nobis. Nobis, who grew up in San Antonio, had begun weight training before arriving at Texas. Nobis started as a sophomore on the 1963 National Championship team and averaged nearly 20 tackles a game before moving on to the Atlanta Falcons.

Charlie Craven on Tommy Nobis and the overall ideal football player.

*Video created using iMovie software

According to Craven, Nobis was a great natural athlete—but he was also a really hard worker in the weight room. As Craven recalls, “At that particular time in our history, we were concerned with shoulder and neck injuries and Tommy wanted his neck to be stronger than everyone’s. According to Craven, they fixed a special station for him so he could specifically train his neck, and, “when the other athletes saw Tommy doing that, and they watched him play, that helped create our interest in strength training a lot.”

By the 1970s the weight program for varsity sports had gained increasing acceptance and Craven was now fully in charge of the program. As acceptance for strength training had grown, however, Craven was finding it increasingly difficult to keep up with all the requests for assistance from various sports and so he asked for permission to hire shot-putting phenomenon Dana LeDuc as an assistant. Following his graduation from UT as an undergrad, LeDuc worked part-time for Craven (who continued teaching in what was now called the Department of Kinesiology and Health Education and supervising student teachers.)

For more on Charlie Cravens visit https://www.texaslsn.org/charlie-cravens

Their dreams came true after the UT Football Team won the National Championships in 2006 and the Athletics Department decided to move forward with the construction of a new building at the North End of the football stadium. UT Athletics Director DeLoss Dodds supported Todd’s proposal to move their collection to the new building and a 27,500SF space was allocated for the Center. The only caveat was that the Todds would have to raise the funds to build the Center. And so, the Todds turned to the Nelda C. and H.J. Lutcher Stark Foundation of Orange, Texas for the lead gift of $5.5M that covered the Center’s construction costs and named the Center in honor of former UT Regent Lutcher Stark. An additional $2M from Joe and Betty Weider and the Joe Weider Foundation to help with operations and exhibits, allowed the Center to move into its new home in the Fall of 2009 and to open the Weider Museum of Physical Culture and the adjacent sports galleries in the Spring of 2010.

The Center is now recognized by the Olympic Committee as an official IOC Research Center (one of only three in the United States), and it has played an increasingly important role in the preservation of the history of UT Athletics. The Stark Center now holds the UT Sports Media Relations Archives as well as personal papers and other memorabilia from many UT athletes and such UT coaching greats as Jody Conradt, Augie Garrido, and Clyde Littlefield, Mack Brown, Harvey Penick, Pat Weiss, David Snyder, and Wilmer Allison.

International scholars from Canada, Italy, Iceland, Austria, Germany, Scotland, Australia, New Zealand, England, Norway, South Africa, France, Denmark, and Ireland have used the Stark Center for research since 2009. The Center has also assisted researchers working on a wide variety of popular books, documentary films, and other projects.

1978- 1992 Dana LeDuc

Charlie Craven discusses Texas’ first full-time strength coach, Dana LeDuc.

The demands on Craven’s schedules finally grew to be so great, however, that he decided he had to step away. Leduc had proved to be an able assistant and so in 1977, Craven met with Darrell Royal and explained that he needed to retire as the strength coach. Craven recommended LeDuc to Royal and so, at a yearly salary of $10,000, Dana LeDuc became the first person at UT to hold the official title of “head strength coach”.

Craven, continued assisting with the strength training after LeDuc was hired and was UT’s representative at the first meeting of the National Strength and Conditioning Association in 1978 in Lincoln, Nebraska. However, after Medina’s retirement, he shifted his duties with Athletics into rehabilitation where he is still involved, even after retiring from the Department of Kinesiology and Health Education in 2008.

While Craven retired from Kinesiology, he has not retired from the Athletics Department where he still works with the football team overseeing injury rehabilitation. According to Jeff Madden, Assistant Athletic Director for Strength and Conditioning, Craven plays an invaluable role on that team.

“He’s the glue that holds us together,” said Madden. “He’s been an inspiring person, an incredible role model for the athletes, and I’ve watched him bring player after player back into shape after their injuries. He’s one of the most impressive and honorable men I’ve met in coaching, and it’s been a real honor for me to work with him all these years.”

When asked to think back on that earlier time, Craven said, “It was just so much fun to see those youngsters improve, even though it was through circuit training and we couldn’t get the pure strength, as we know it today, but they did get absolutely stronger and never entered a game, back in that time, where we thought the fourth quarter would be anyone’s business but the University of Texas at Austin. We took over. I get a lot of satisfaction out of seeing the strength and conditioning program today compared to where it was when I started. To tell you the basic difference, I tell you, back in that time, as I’ve said in earlier comments, I had the entire offense for one hour and the entire defense for one hour. I could not take into account the individual differences, and individual needs by position, because that was the only time that Coach Royal would allow. Since I was working at his pleasure, I certainly followed his directions. So, that was the first model. Just circuit training. Now, we have every program and every sport is individualized to where every youngster has records on computers and we have normal progressions, periodization concepts, and all of this. We have taken science to a real new height in the strength and conditioning programs in America. We have done that here too at the University of Texas.”

For more information on Dana LeDuc visit https://www.texaslsn.org/dana-leduc

1982 Longhorn team captain and nine-year player for the Seattle Seahawks Bryan Millard, said, “I cannot tell you how valuable Dana LeDuc was because of his strength training. I played with some very good offensive linemen who played not only at Texas but went on to have extended careers in the NFL, and a lot of that had to do with Dana LeDuc.

1976- NCAA Shot Put Champion

Southwest Conference Championship Titles In The Shot Put In 1974, 1975, And 1976

HOH inductee In 1997

In 1986 Dana went directly to the European weight lifting manufacturers to purchase state-of-the-art equipment and computerized aerobicyles for conditioning for the Neuhaus-Royal facility.

Dana LeDuc is the first person at UT to hold the official title of “head strength coach”.

LeDuc states, “I really believe there is no type of athlete that weight training and strength work can’t help.” LeDuc believes in utilizing strength and flexibility exercises to combat joint injuries.

LeDuc’s coaching philosophy is based on strength development as a means to increase on-field performance for football players. He allows athletes to transition into more power and sport-specific movements once a standard level of strength is attained.

LeDuc also believes that athletes’ conditioning will improve by the use of “quick bursts of speed over shorter distances” compared to the “lap after lap” of long-distance runs. He also adds Olympic weight lifting techniques to mirror the physiological demands of football.

LeDuc left Texas in 1992 after accepting a job as the head strength and conditioning coach at the University of Miami.

For more about Dana LeDuc visit https://www.texaslsn.org/dana-leduc

1992- Jeff Moore the women’s tennis coach says that without strength Coach Angel Spassvo’s work on his team there would not have been a National Championship team for women in tennis.

1983 The Todds returned to the faculty at Texas

The Todds joined the faculty at the University of Texas in 1983, bringing with them 380 boxes of books, magazines, photos, artifacts, materials and a $25K gift from Terry’s former weightlifting coach, Roy J. McLean, and the gift of Mclean’s own collection of strength-related materials. It was the official beginning of what is now known as the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center. The Todds have continued to accumulate more materials for their collection—described in 1999 by sports historian John Fair as “the single most important archive in the world” in this field.

In return for McLean’s generosity, the Todds began calling their collection the Todd-McLean Physical Culture Collection, and the collection is cited in numerous books and journal articles from the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. The Todds also started actively acquiring other collections in the 1980s and by the time the Todd-McLean Collection moved into the Stark Center in 2008-2009, their collections had grown to several thousand boxes and their book collection took more than 100 book carts to move.

1993-1997 Roger Gullickson is hired by John Mackovich as head strength and conditioning coach

Roger “Rock” Gullickson accepted the head strength and conditioning position at The University of Texas in 1993 under head football coach John Mackovich. In his early years before Texas, Gullickson competed as a drug-free powerlifter, became the Montana state champion from 1983-1986, and had an eighth-place finish at the U.S. National Powerlifting Championships in 1986. Following his success at Montana State, Gullickson was hired by Rutgers University where he was in charge of strength and speed development for the Scarlet Knights football team for three years.

Gullickson’s success at the University of Texas was due to his ability to ignite competition in the weight room. Honor boards showing current record holders in various exercises displayed around the weight room sparked competitiveness among the players.

The boards were comprised of school record holders and current team record holders for the given lifts by position. As a result, Gullickson witnessed large jumps in strength measures, such as double the number of 400-pound bench pressers and tripling the 300-pound power cleaners among the team from 1992 to 1993. This success garnered praise from Coach John Mackovic who said, “Rock has put a program in place that is goal-oriented and helps to build success for players off the field. The progress our team has made in the past twelve months has been dramatic.”

Another tactic Gullickson used was the Iron Man competition, in which players would compete against one another to discover who was in the best condition at the various positions. With this tactic, Gullickson was able to challenge his athletes, such as offensive lineman Dan Neil and Blake Brokermeyer, outside of practice. During his tenure, Gullickson witnessed Iron Man battles translate to numerous Longhorn weight records, including Neil and Brokermeyer, both of whom set the push jerk mark at 385 pounds, a new record at the time.

Although Gullickson was a strong advocate for raw strength, he also challenged the players to other areas, such as agility and power movements. Gullickson would test vertical jumping and “jingle jangles” (a measurement of agility) as ways in which skilled positions could demonstrate their ability.

Throughout his career at Texas, Gullickson witnessed the athletes’ weight lifting numbers increase as a result of the competition in the weight room. In 1995, Gullickson had just 10 players squat over 550 pounds and 15 players recorded a vertical jump of 32 inches or more. In 1997, 15 players squatted more than 550 pounds and 21 players jumped 32 inches or higher. One particular athlete, defensive tackle Chris Atkins, broke nearly every Longhorn lifting record during his tenure at Texas. By his senior year, Atkins set marks in the squat, bench, and power clean of 760 pounds, 556 pounds, and 363 pounds, respectively. Atkins credited his on-field performance to his work in the weight room when he said, “I don’t think I’d be playing at a Division I school without the strength I have,” said Atkins. “It would be hard for me to see any program better than ours as far as strength and conditioning.”

Gullickson believed that player competition in the weight room would lead to success. He is right. The players get stronger, and Coach Mackovic is pleased. He says, “Rock has put a program in place that is goal-oriented and helps to build success for players off the field. The progress our team has made in the past twelve months has been dramatic.”

After Texas, Gullickson joins New Orleans Saints, Green Bay Packers, and the St. Louis Rams as the strength and conditioning coach.

“Look like Tarzan but play like jane”

Weight lifting is only one factor in winning- 1997 proves that point-

Weight lifting, strength, and superior vertical leap are only one component of team wins. The formula for winning requires great recruiting, a competent coaching staff, great players, inherent trust in the system, team chemistry, a strong work ethic, and a little luck. If a team does not have these qualities, then strength and conditioning will not create a winner.

The 1960s represented a decade when conditioning was important, but weight lifting was not. Seven teams from 1961-to 1970 had a combined record of 77-5-2 and won three of the four Longhorn National Championships. Vertical leap and strength did not win those games.

Strength and conditioning are ancillary not the catalyst to winning. In 1995 Texas had ten football players squat over 550 pounds, and 15 players recorded a vertical jump of 32 inches or more. Texas’s won-loss record that year was 10-2-1.

In 1997 Texas had 15 players squat more than 550 pounds, and 21 players jumped 32 inches or higher. Texas record was 4 -7. The O.U. Sooner players said this Longhorn team was in poor condition. One Sooner said, “We flat wore their ass out.”

John Hagy 1985-1987,

John Hagy was 100% right when he said, “How much I could bench press didn’t have a whole lot of bearing on how good a football player I was.” The human spirit and drive to excel beats the bench press every time.

John as a freshman at Texas could not bench press 135 pounds. Dana LeDuc, the strength coach, told John that he would never smell the field until he benched pressed 300 pounds. Two weeks later, John Hagy started against Auburn and Bo Jackson. John says weight lifting and conditioning are necessary, “but it can also be “overrated.” “Certain things will make you a better football player. But it doesn’t mean you can’t be a good football player just because there’s this one condition you can’t meet.”

1995 Trey Zepeda Interns with UT and is hired in 1997 as the assistant strength and conditioning coach.

Trey Zepeda was busy in his youth, growing up as a rodeo kid on a ranch in southern Texas while participating in many different sports. He remembers training for football, basketball, baseball, and track and field. However, during his time at Ottawa University in Kansas, Zepeda narrowed his focus to football and baseball.

Prior to his collegiate career, Zepeda gained valuable knowledge that would lead him to his current profession in weight training. During his junior year of high school in Vanderbilt, Texas, Zepeda came in contact with Dave Goodin, a professional bodybuilder, and personal trainer. Goodin taught Zepeda the techniques for and the reasoning behind various exercises during training periods. Zepeda attests that “some of the things I took from those early sessions [with Dave] are what I still use with my athletes now, [specifically] the principles of what a lift is and how those movements apply differently to the body.”

Zepeda had gained a strong weight lifting base from Goodin, and it propelled him within the weight room. He excelled in comparison to his peer during his time at Ottawa. During this time, there was a lack of scheduled team training sessions, so Zepeda would often time help and teach his own teammates. “I didn’t realize it then, but I was actually coaching [my peers] and not even knowing it,” said Zepeda.

After college, Zepeda played professional football in the arena and European leagues as a linebacker, before enduring a career-ending shoulder injury. With his football career moving into the past, Zepeda turned to the radio industry and used his business degree during his transitional period away from athletics.

In 1995, Zepeda discovered that weight training was a legitimate profession, and he so reconnected with Goodin at Hyde Park gym in Austin, Texas. Zepeda assisted Goodin in managing the gym, in addition to interning at The University of Texas’ strength and conditioning department. A few years after he began his internship with the Longhorns, Zepeda was hired as the assistant strength and conditioning coach. His primary sports currently include men’s track and field, men’s golf, and men’s swimming.

Zepeda’s main concern as a coach is finding the strengths and weaknesses of his athletes at Texas. Once he has determined each athlete’s specific weakness, Zepeda uses his experience in the Olympics and powerlifting, as well as his functional movement science knowledge, to enhance performance and adjust movement discrepancies for each athlete. As a result, Zepeda’s influence in the weight room has assisted in three top-five finishes at the NCAA Golf Championships, including a 2012 National Championship in men’s golf, four NCAA Championships in men’s swimming, as well as numerous NCAA and Olympic track and field champions during his tenure with the Texas Longhorns.

1997

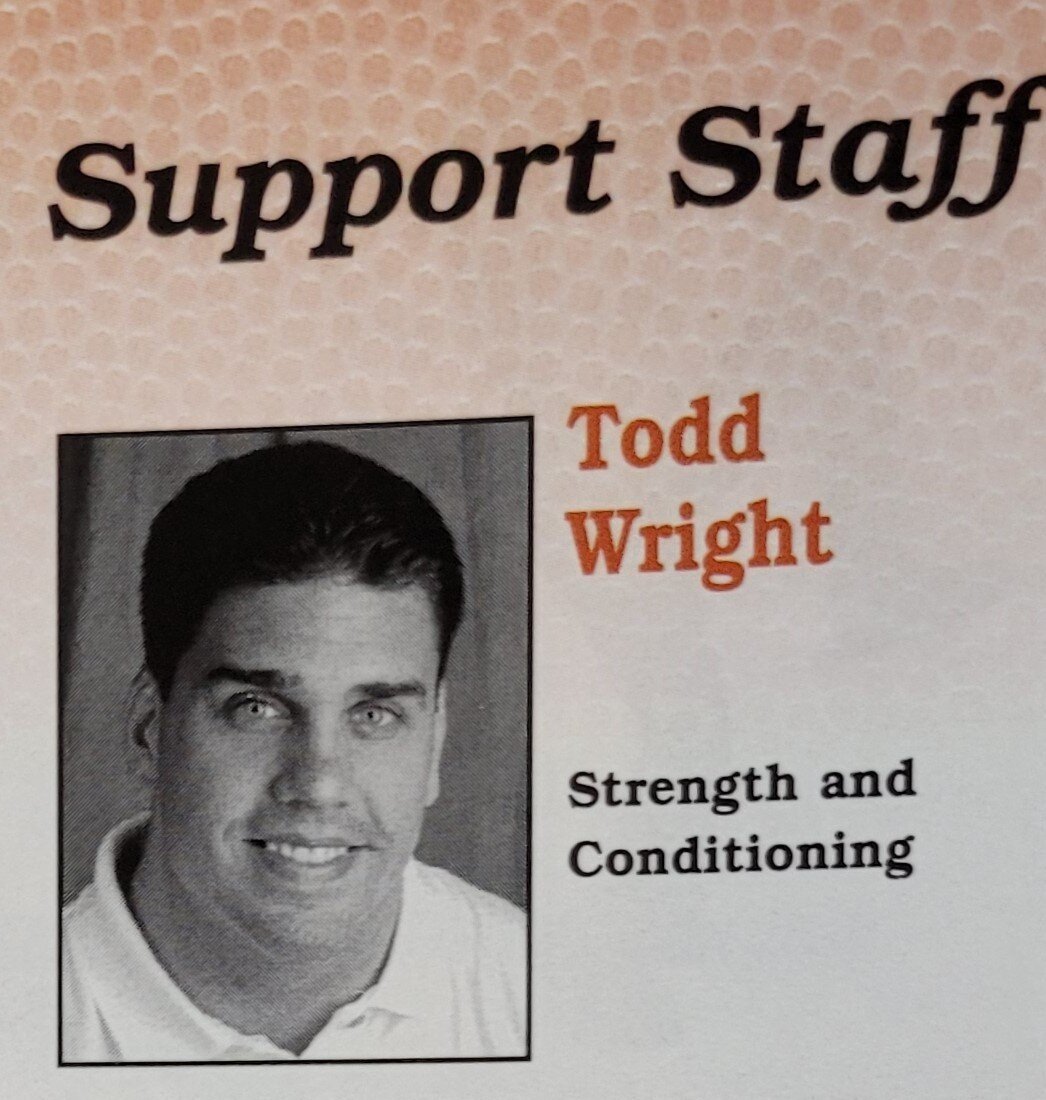

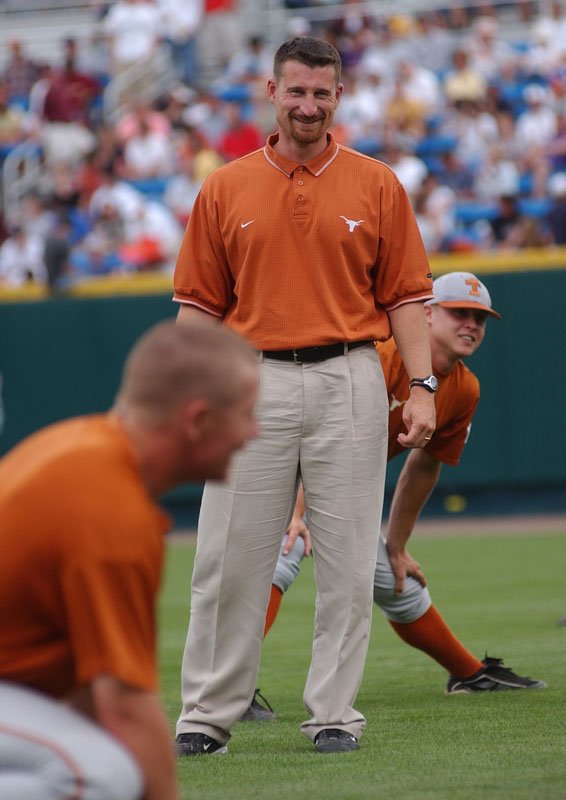

Todd Wright – 1998

Todd Wright worked closely with Coach Rick Barnes converting skinny tall guys into muscle with staminal.

Todd Wright has been part of the strength and conditioning staff at the University of Texas at Austin since 1998. Wright followed Coach Barnes to the University of Texas as the head of strength and conditioning for men’s basketball. His training technique develops the natural physical talents of his players through the use of sport-specific methods of conditioning.

Wright is known for the “Vertical Core Training System,” This system is incredibly productive for basketball players. Still, it is really “sport-specific” This process is used to improve the power and flexibility of the muscles used in their chosen sport. Wright says, “The will to win means nothing without the will to train.”

Todd Wright has been part of the strength and conditioning staff at the University of Texas at Austin since 1998. Although Wright played football in high school and at Springfield College in Massachusetts, he became more interested in basketball after he joined the Clemson strength and conditioning program and met Rick Barns, the men’s basketball coach at Clemson. Impressed by Barnes’ coaching skill and commitment to hard work, Wright followed Barnes to the University of Texas as the head of strength and conditioning for men’s basketball. Over his 13 years at UT, Wright has become widely admired around the country for his ability to amplify the natural physical talents of his players through the use of sport-specific techniques of conditioning.

During Wright’s last 13 years at UT, the men’s team was selected to participate in the NCAA Tournament every year, compiling 322 wins against only 123 losses, a standard never achieved before by a UT team. Moreover, only five other basketball programs in the U.S. went to the NCAA Tournament in each of those years. What’s more, Texas advanced to the “Sweet 16” during five of the last ten years, won a trip to the Final Four in 2003, and reached the “Elite Eight” twice—in 2006 and 2008.

These accomplishments were made possible by the outstanding physical conditioning and genetic aptitude for the sport exhibited by such notable UT players as T.J. Ford and Kevin Durant, who won Player of the Year titles—Ford in 2003 and Durant in 2007. In addition, 16 Longhorns were drafted by the NBA, and ten were selected in the first round. In fact, over three years, from 2006 through 2008, Texas was the only school with a top ten pick every year. Of course, some of this success is due to recruiting, but it would not have been possible without the sophisticated training programs and personal leadership of Todd Wright.

Wright is becoming increasingly well-known because of what he calls the “Vertical Core Training System,” which is his unique approach to training the muscles which link the pelvis to the rib cage in ways that will transfer to the basketball court. Many people use the phrase “core training,” but few understand how such training can enhance the power and flexibility of the muscles in ways that will improve any man or woman in his or her chosen sport. Wright believes that such training needs to be done with the body vertically, with the feet used to “anchor” the body and allow the target muscles to be properly “loaded.”

Watching Wright put his team through a session of Vertical Core Training is to understand why Player after Player will say, “I trained with weights and conditioning drills in high school, but I’ve never done anything like what we do here at Texas. I’ve never felt as quick and explosive as I do now, even though I’ve gained some weight since I arrived.” Of course, an average Todd Wright workout may include such classical barbell lifts as the power snatch. Still, it will probably also include exercises like speed push-ups, heavy ropes, loaded vertical jumps, medicine ball drills, expanding bands, dumbbell work, and lots of patterned agility sprints focusing on quick transitions and staying low.

One of the maxims Wright lives by is that “The will to win means nothing without the will to train,” and the intensity he exhibits as he puts his players through their paces is proof that he will give all he has to help them unwrap their gifts for this exciting sport and take their talent as far as they will let him. They realize this, and they respect him for what he can do for them if they’ll only listen to him when he says, “You’ve got to bring it every day.”

Nor is Wright only interested in elite athletes. The father of three school-age children, he worries that because some parents and coaches want to channel young athletes into just one sport, the boys and girls who go down that narrow path will fail to develop the basic motor skills they would get if they practiced more sports and the training exercises specific to those sports. “Back in 1992, physical education was eliminated from the Texas public school system,” he points out, arguing that just as reading and math promote cognitive development, the physical motor patterns are only developed if a variety of sports and exercises are done as they used to be done in public schools in basic physical education classes. “My recommendation,” he says, “would be for parents to urge their children to experiment with a number of different sports. They’ll develop more completely and be less likely to sustain injuries once they begin to concentrate on one or two sports.”

1998- Assistant Athletics Director for Strength and Conditioning Jeff “Mad Dog” Madden

His high school coach gave Madden his nickname “Mad Dog” due to his aggressive and persevering nature. After high school, Madden attended Vanderbilt University, earning a letter in football for three seasons. Madden spent time at the University of Cincinnati, Rice, and the University of Colorado, honing his skills as a strength and conditioning coach. At Colorado, he coached and trained two back-to-back national championship-contending teams, with one national championship team in 1990, three straight Big Eight championships, four bowl games, and one Heisman Trophy winner, Rashaan Salaam. In addition, he coached over 65 players who would go on to play professionally, several Pro-Bowlers, one Butkus award winner, one Thorpe award winner, countless All-Americans, and 1st-round NFL draft picks, all at the University of Colorado.

John Madden followed Mack Brown from North Carolina to Texas in 1998. He has been selected as a four-time National Strength Coach of the Year.

Mack Brown says of Coach John Madden, “Jeff has a gift in dealing out “Tough Love” that sends a message and builds a special bond between Jeff and the players.”

Madden’s first job at Texas was re-designing the Nasser Al-Rashid weight room. Like LeDuc, He emphasized speed and explosive power rather than only brute strength. He combines flexibility and Olympic lifting techniques to enhance the player’s performance.

Click on the link to see Madden’s mean and tough list.

https://www.texaslsn.org/maddogs-mean-and-tough-list

Madden then joined Mack Brown at North Carolina at Chapel Hill and became the associate head athletic director and head strength and conditioning coach. At UNC, the football team went to six bowl games, and he coached over 70 NFL players. Finally, Madden went to the University of Texas with Mack Brown in 1998.

At Texas he re-designed the Nasser Al-Rashid weight room, making this the fourth facility design of his coaching career. The facility encompassed 20,000 square feet of space with 900 square feet designated as a plyometric training area and another area dedicated to a three-lane, 70-yard track. Madden outfitted the facility with the purpose of making it state of the art and providing the best opportunity for Texas athletes to optimize their performance.

His goal was to emphasize speed and explosive power rather than solely brute strength. Some of Madden’s early work with UT athletes incorporated an aerobic base of fitness as the initial conditioning phase. Later, Madden shifted his athletes to interval training, ultimately having players progress from 4:1 rest to work ratios to a 1:1 rest to work ratio, in order to imitate the high-powered, fast-paced offenses in football.

Madden also employed a Bulgarian wave system, focusing on the power clean. As a result of his rehabbing experiences in Cleveland, Madden believed that “Olympic lifting” movements could enhance an athlete’s performance. Yet Madden did not stray away from variation for his athletes. He exemplified this by his use of machines to correct imbalances and rehab injured athletes. Flexibility and hand-to-hand combat training were also programmed by Madden, simulating a more “sport specific” realm for his players during his off-season sessions. Madden believed that using these various means of training “helped translate during practice and helped football coaches see these differences for a more efficient athlete during the fall.”

These aforementioned strategies produced results in only a year’s time. From his initial hiring in 1998 to the end of the summer in 1999, there were more than forty UT football players with a vertical jump of at least 30 inches and more than twenty-two athletes who could bench press more than 400 lbs and squat at least 500 lbs. Additionally, Madden also saw Dan Neil’s school record in the power clean broken by four of his athletes by an average of twenty pounds. Madden was also astonished by the physical transformation of his later athletes. Madden recalls seeing athletes such as Colt McCoy going from a “168 pound boy to a 210 pound man.”

Additionally, Brian Orakpo looked like a “basketball player” when he reported at 207 pounds his freshman year, but transformed himself into a 264 pound NFL first round draft pick able to bench press 525 lbs.

One central tenet to Madden’s training was his focus on mental strength. According to Madden, “strength training is transforming boys to men and getting them tougher and preparing them for competition.” He also emphasized strength and conditioning as “team building,” and stated that it establishes “team camaraderie; attempting to get 120 football players going in one direction.”

Madden’s tough mental preparation along with his grueling physical training for his athletes led to his idea that “allowing kids to get stronger [helps] them gain confidence—and confidence produces winners.”

Madden is also a large advocate for helping athletes realize their life-long dream of becoming NFL players. During certain training weeks, he emulated NFL combine tests in order for the athletes to test better during the Longhorn Pro Day. Madden said this “kept the kids from getting false hope so they could truly become the best they can be.” As a result, Madden has contributed to the training of more than 235 NFL players, with 34 of those being drafted in the first round.

Madden’s strength and conditioning body of work led to a long list of accolades. Two of his players were Heisman Trophy winners – Rashaan Saalam in 1994 and Ricky Williams in 1998 – and two were up for the award, Vince Young in 2005 and Colt McCoy in 2008. Madden also played a role in National Championship seasons in 1990, 1991, and 2005, and helped the Longhorns reach the national championship game in 2009.

He has also contributed to the success of other sports such as track and field; sixteen-track and field athletes competed in the Olympics while under Madden’s guidance. Overall, more than 40 athletes competed in the various sports in the Olympics under Madden’s guidance. In 2003, Madden was inducted into the USA Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association’s hall of fame. In May of 2009, Madden was elected as president of the Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association (CSCCa). He is among a small group of coaches that earned the title of Master Strength and Conditioning Coach, the highest honor that can be achieved by a strength and conditioning coach in the CSCCa. Other awards achieved by Madden include the National Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coach of the year in 2004, and the Culligan Holiday Bowl’s Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp Trophy in 2000.

Trey’s primary responsibility includes men’s track and field, men’s golf, and men’s swimming. He focuses on teaching the athletes what a lift is and how those movements apply differently to the body to find his athletes’ strengths and weaknesses. Once he has determined each athlete’s specific weakness, Zepeda uses his experience in Olympics and powerlifting and his functional movement science knowledge to enhance performance and adjust movement discrepancies for each athlete.

1998 and Beyond

Bennie Wylie- 1998

Wylie, a graduate of Sam Houston State University, was also a football letterman from 1994-to 1997 as a running back. He was selected “Freshman of the Year” in 1994 and All-Southland Conference honors during his senior season in 1997.

In 1998, Wylie was named Interim Head Strength & Conditioning Coach for his alma mater, followed by a three-year stint as Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach for the Dallas Cowboys under former Head Coach Chan Gailey. During his career in Dallas, Wylie coached players such as Emmitt Smith and Troy Aikman, and in 1999 the team earned a playoff appearance. In 2002, during his last year with the Cowboys, Wylie also worked as the head strength and conditioning coach for the Dallas Desperados arena football team.

Wylie returned to the collegiate level at Texas Tech University as the Head Strength Coach in 2003 under former coach Mike Leach. For the next seven years, Texas Tech accumulated a 46-18 record, with the highlight being an 11-2 record in 2008, and a trip to the Cotton Bowl. Following his career in Lubbock, Wylie became the Head Strength and Conditioning Coach for the University of Tennessee during the 2009- 2010 season under Coach Derek Dooley.

In January 2011, Wylie moved to another UT and to a darker shade of orange when he came to the In University of Texas. A believer in “hard-nosed work,”

Wylie is known to program high-intensity weight room sessions to better mimic a more game-like setting for the players.

In addition to his work ethic, Wylie has coached more than fifteen NFL draft picks, including Michael Crabtree, Keenan Robinson, Kheeston Randall, and Emmanuel Acho. He has also coached a Biletnikoff award winner in Michael Crabtree, an AT&T All-American Player of the Year, and a Heisman Trophy finalist in Graham Harrell.

Click here for a look at Bennie Wylie’s offensive line and defensive line specialty workout.

Click here for a look at Wylie’s wide receiver workout.

In January of 2011, Wylie replaced Jeff Madden. He has a “hard-nosed work,” ethic and participates with the players in weight lifting and conditioning workouts. As a philosophy, Wylie believes that participating allows him to fully experience what the athlete endures on a daily basis during the off-season. Wylie believes in game-like setting high-intensity weight room sessions to prepare the athletes for a game.

Donnie Maib-1998

Maib found his direction in strength and conditioning thanks to a former mentor, Dr. E.J. “Doc” Kreis.

Kreis had introduced Maib to Olympic lifting techniques before his senior season at Georgia. Maib realized how his athletic potential could be enhanced from his summer sessions with Kreis, and he attests that his explosiveness and athleticism changed on the playing field because of the similar movement patterns he learned from the clean, jerk, and snatch. In addition, Maib would follow his off-season training with his best season as a Bulldog defensive tackle.

Upon graduating from the University of Georgia in 1993, Maib accepted a six-month internship in Boulder and followed Coach Kreis to the University of Colorado. After just two years, his internship turned into a full-time assistant strength and conditioning position for Colorado. After working under Kreis, Maib accepted a position under Coach Jeff Madden at the University of Texas in 1998 as an assistant strength and conditioning coach.

Since 1998, Maib has primarily assisted in coaching the football team, but today, he is in charge of men’s tennis and women’s volleyball. During his coaching career, Maib has instilled the principles he learned from Olympic lifting and and what he calls “addressing weaknesses and improper movement patterns” using “functional training.”

Maib does admit that the evolution of strength and conditioning has changed from when he first began in the field. Specifically, he has seen changes in coaching philosophy, which is increasingly focused on injury prevention rather than bodybuilding. In addition, more teams and sports need individual treatment and coaching from strength and conditioning coaches rather than simply football teams having full access.

Maib’s view is that a strength and conditioning coach can “enhance work ethic, leadership, and physical and mental toughness,” which can grant “a team a major edge during competition.”

Maib’s influence in the weight room has helped guide numerous teams to successful seasons, most notably in 2008 and 2009, with the Longhorn men’s tennis and women’s volleyball teams earning runner-up honors in each of their National Championship games. In addition, Maib was a part of the 2005 National Champion football team as an assistant strength and conditioning coach. In 2011, as a credit to his positive influence, successes, and numerous accolades from the weight room, Maib was promoted to head strength and conditioning coach of Olympic sports at the University of Texas.

From 1999 to the present, Sandy Abney has been a strength and conditioning coach

As a high school track and field star, she was introduced to powerlifting early, which she considers beneficial to her performance in throwing and sprinting events. She earned a scholarship in 1993 to become a heptathlete for Southwest Texas State University (now Texas State University), where she competed in weightlifting. With the help of former Bulgarian strength coach Angel Spassov, Abney was introduced to Olympic weightlifting. After finishing her collegiate track and field career, Abney continued to train in Olympic movements. In 2004, she competed for a spot on the USA Olympic weightlifting team (although she was just short of making the team), and in 2009, she was crowned the 2009 Master Olympic Weightlifting National Champion.

Abney was hired as a strength and conditioning coach for the University of Texas during her training in 1999. She remembers the rigorous twelve-hour days of training multiple groups and finding time to train herself. Although female strength coaches were a rarity then, Abney believed her athletes could relate more to her coaching style because of her knowledge and experience.

She now attributes her past weight room achievements to “informing the athletes that I’ve been an athlete and a weight lifting competitor, so I know what they go through during a season.” In addition, Abney believes that being a strength coach is “like an art” and says she was drawn to strength and conditioning because of the ability to “manipulate the body to perform a certain way to optimize performance and get the athletes to adapt their abilities.”

Abney’s philosophy has allowed her to become the head strength coach for Texas’s softball, rowing, and women’s swim teams. Additionally, Abney has seen her teams compete for twelve national championships and won more than twelve Big 12 Conference Championships. Abney has also trained eight Olympians, four gold medalists, during her career as a Longhorn. Her success in male-dominated fields is a testament to her dedication and talent.

2004 Lance Sewell

Sewell began volunteering for Baylor Coach Rogers, and after two years under Rogers, he was offered a paid position as a strength and conditioning intern with the Chicago White Sox under former strength coach Vern Gambetta. Sewell’s relationship with Gambetta allowed him to experience various levels of professional baseball, from the Prince William Cannons in northern Virginia to the Bristol White Sox in Bristol, Virginia. After volunteering with the White Sox, Sewell was hired as a graduate assistant in strength and conditioning under former coach John Stuckey at the University of Tennessee.

After his time in Knoxville, Sewell reunited with Gambetta as the Director of Conditioning with the Cincinnati Reds. He began to educate professional athletes on the importance of strength and conditioning from an injury prevention standpoint, compared to that of bodybuilding. His experience in the ranks of Major League Baseball presented him with an opportunity to become an assistant strength coach with the University of Miami at the end of the 2001 season. Sewell was primarily assigned to train the baseball team, but he was also able to help with football, track and field, and swimming during his time at Miami.

In 2004, Sewell was hired as an assistant strength coach at the University of Texas. For the first four years of his tenure, he was able to assist Coach Madden. Throughout his time at Texas, the main team he has trained is baseball, however, he has also coached softball, women’s golf, and cheer and pom.

As a strength coach, Sewell’s philosophy consists of improving athletic performance through sport-specific exercises that supplement injury preventive movements. His emphasis on tri-planar (i.e sagittal, frontal, and transverse) exercises allows his athletes to become better prepared for competitions. Furthermore, Sewell’s training theory is to train athletes on their feet because “most sport is played standing,” which allows for a more functional athletic environment.

Part of his philosophy stems from traditional linear progression, while his main muscle movements are based around the central nervous response of the individual athlete. As a result of his coaching and training methodology, Sewell has helped the Longhorns to one National Championship in 2005, three trips to the College World Series in 2004, 2005, and 2009, as well as six Big XII Conference Championships.

Lance Hooten

2005 – Jan and Terry Todd’s dream comes true

After the UT Football Team won the National Championships in 2006, the Athletics Department decided to move forward with the construction of a new building at the North End of the football stadium. UT Athletics Director DeLoss Dodds supported the Todd’s proposal to move their collection to the new building and a 27,500SF space was allocated for the Center. The only caveat was that the Todds would have to raise the funds to build the Center. And so, the Todds turned to the Nelda C. and H.J. Lutcher Stark Foundation of Orange, Texas for the lead gift of $5.5M that covered the Center’s construction costs and named the Center in honor of former UT Regent Lutcher Stark. An additional $2M from Joe and Betty Weider and the Joe Weider Foundation to help with operations and exhibits, allowed the Center to move into its new home in the Fall of 2009 and to open the Weider Museum of Physical Culture and the adjacent sports galleries in the Spring of 2010.

The Center is now recognized by the Olympic Committee as an official IOC Research Center (one of only three in the United States), and it has played an increasingly important role in the preservation of the history of UT Athletics. The Stark Center now holds the UT Sports Media Relations Archives as well as personal papers and other memorabilia from many UT athletes and such UT coaching greats as Jody Conradt, Augie Garrido, Clyde Littlefield, Mack Brown, Harvey Penick, Pat Weiss, David Snyder, and Wilmer Allison.

International scholars from Canada, Italy, Iceland, Austria, Germany, Scotland, Australia, New Zealand, England, Norway, South Africa, France, Denmark, and Ireland have used the Stark Center for research since 2009. The Center has also assisted researchers working on a wide variety of popular books, documentary films, and other projects.

Lee McCormick 2002-2006; 2008 to

In 2002 He was hired as an assistant at The University of Texas and worked with football, basketball, softball, and baseball over the next four years. While in Austin, he also worked some with boxers and an AAU basketball team which led to an invitation to join the Spurs organization in San Antonio in 2006.

In 2008, however, McCormick received a phone call from Jeff Madden that changed his career once again. Madden invited McCormick to return and rejoin the staff at Texas.

Since returning to Texas, McCormick has assisted with football and track….

At Murray State University in early 1983, Lee McCormick tried out for the football team as a walk-on football player and ended his playing career two years later as the school’s all-time leading receiver. McCormick, who now works with football players as well as several other sports at the University of Texas as a strength coach, learned a lot from that experience. “It was a lot of hard work being a walk-on because I had to prove myself,” McCormick said. “I was new to the system but I adjusted pretty fast.” In fact, McCormick adjusted so well that he earned both All-American and All-Ohio Valley Conference honors during his senior year and he has since been inducted into the Murray State Athletics Hall of Fame. At the time of his induction, in 1996, McCormick held the career record for receptions (122) and receiving yards (1,837) at his alma mater.

Following graduation in 1986, McCormick played Arena Football for a few years, and attended several NFL camps but finally realized he wasn’t going to have an NFL career. So, for several years he worked in various aspects of the insurance industry and then, in 2002, decided to return to his first love and become a strength and conditioning coach. He was hired as an assistant at The University of Texas that year and worked with football, basketball, softball, and baseball over the next four years. While in Austin, he also worked some with boxers and an AAU basketball team which led to an invitation to join the Spurs organization in San Antonio in 2006. There McCormick worked with both the Spurs and the Women’s National Basketball Association’s San Antonio Silver Stars, before deciding to take another college job as an assistant at New Mexico Highlands University. However, McCormick was there hardly more than a year when he was invited to be the head strength coach at Indiana State University in Terre Haute, Indiana. For McCormick, who grew up in Indiana, it was a true homecoming and he reports that he thoroughly enjoyed his time working with the ISU Sycamores.

In 2008, however, McCormick received a phone call from Jeff Madden that changed his career once again. Madden invited McCormick to return and rejoin the staff at Texas. Said McCormick of the move back to Texas, “I want to thank ISU for the opportunity to work as a Division I strength coach and head up my own program. I will always be thankful for that opportunity.” However, he told reporters, the chance to return to Texas was just “a great professional opportunity for me. To be asked back to help with…their strength program was something that I could not turn down.”

Since returning to Texas, McCormick has assisted with football and track and additionally forged an unusually rewarding coaching relationship with Olympic diver Troy Dumais, who graduated from UT in 2006, but he still spends a portion of every year in Austin where he trains with McCormick and diving coach Matt Scoggins. Dumais, a four-time Olympian, was the subject of a pre-Olympic TV feature about his training with McCormick prior to the Games. Dumais is the only American diver other than Greg Louganis to make four Olympic teams, and in London, he finally won a bronze medal in synchronized diving. To see McCormick and Dumais talk about training click here.

2011 Shaun McPherson

Shaun joined Texas in 2011 and is presently the assistant strength & Conditioning Coach for women’s basketball. He is one of the reasons for the successful Baylor women’s basketball program and is a major reason for the success of the 2015-2016 basketball team. Shaun also administered strength and conditioning in Track and Field, Tennis, baseball, and football at Baylor.

-

Edwina Brown 1996

Former Texas standout Edwina Brown (1996-2000) joined the Longhorns staff as strength and conditioning assistant coach for Women’s Basketball.

“We are so happy to have Edwina on staff,” Goestenkors said. “She will bring her mental and physical toughness, along with her vast knowledge of the game, to our program. `Wink’ knows what it takes to be the very best player in the country, and she will be a vital asset to the future of Texas Women’s Basketball.”

Basketball weight room

2012

Rowing Work-out

Eating Right

2013

Page Elizabeth Bauerkemper, in her 2013 report titled Beyond Sports: A Guidebook for Potential Collegiate Female Student-Athletes, states that “female student-athletes are at risk for developing disorder eating patterns……….” “most estimates fall between 14 and 27 percent “. Men have the same eating disorders, but there is no data to quantify the severity of the problem. Regardless, the University of Texas dietitians understand the issue and are “diet active” in reducing the disorder.

The key to success for healthy nutrition is the responsibility of the student-athlete. “Nutritionists, strength, and condition trainers can offer eating guidelines, but it is the athlete who makes the final decision on food intake. Unfortunately, many athletes choose not to comply with the food regimen.

Eating Right

2013

2014