Tony Crosby

Coach Royal was once asked by the media how to coach a kicker. Royal said, “You don’t.” The writer then said, “Then how do you pick one? Royal responded, “You take the boy who kicks it the farthest.” Meet Tony Crosby, the guy who could kick it the farthest and, may I add ACC, accurately.

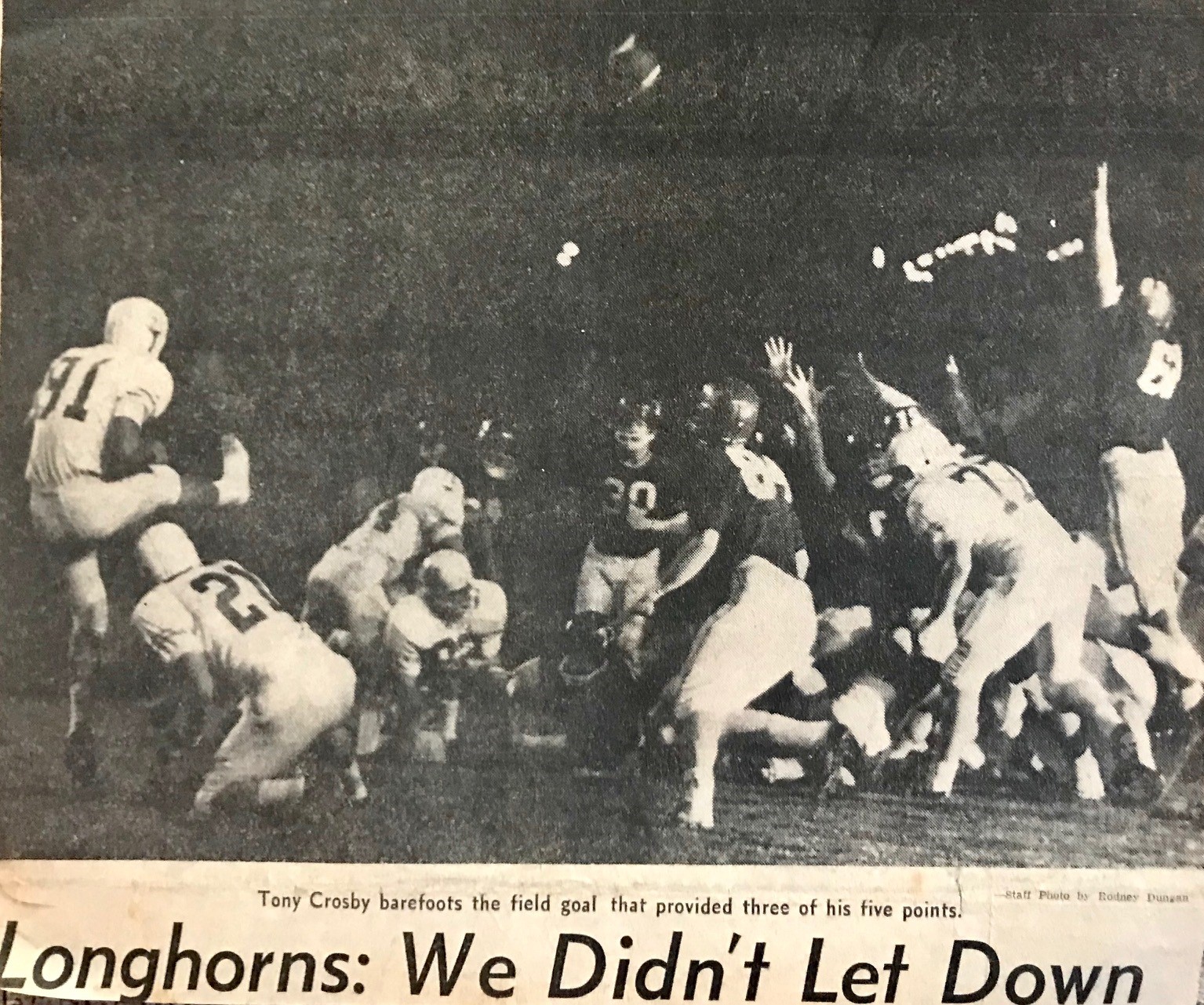

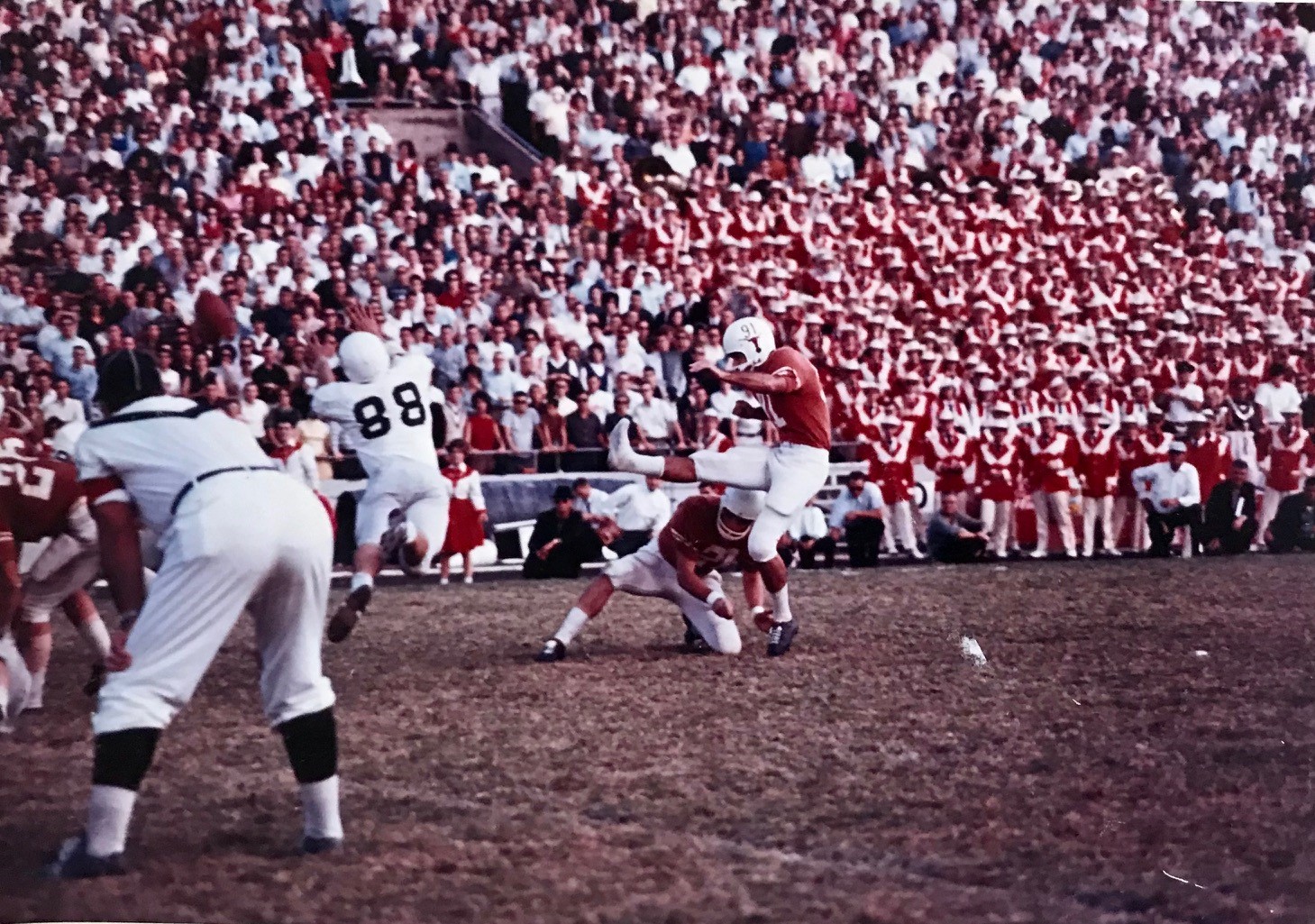

Tony Crosby- Shoeless/stockinged/barefoot kicker’ Crosby was an unsung difference-maker in 1963

By Gaylon Krizak

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1554322122608_21824 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid { margin-right: -20px; }

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1554322122608_21824 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid-slide .margin-wrapper { margin-right: 20px; margin-bottom: 20px; }

But before Gaylon’s article A special memory from from1963 student manager Roy Jones about Tony Crosby and Billy Schott.

Billy,

I enjoyed the article on Tony Crosby. We spent four enjoyable years at UT together. The article fails to mention what made Tony so unique as a placekicker.

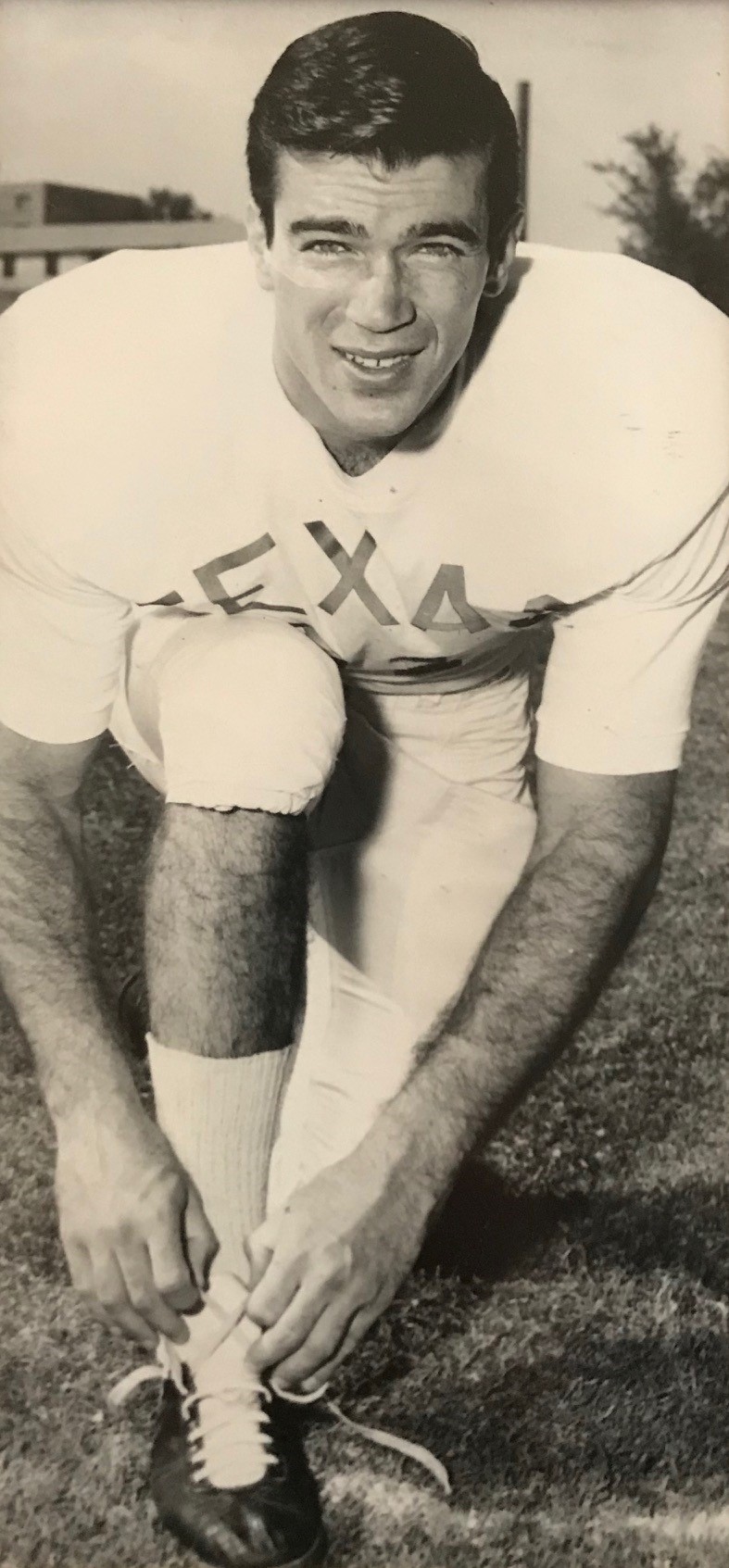

True, he kicked without a shoe, but he didn’t address the ball with his toe like all other straight-on kickers of the day (or with his instep like the soccer-style kickers do now).

Tony was able to get quicker height on his placement kicks because he turned up his toes and impacted the football with what is commonly called the “ball” of the foot. (For podiatrists I would say he impacted the ball with the sole of the foot approximately where the phalanges — the toe bones– and the metatarsals are connected.)

One of my jobs as student manager on game day was getting the kickoff and placement tees on and off the field. My freshman year I also had to keep up with David Kristynik’s kicking shoe — which had the toe box cut out so he could impact the ball with his bare toes.

A bit of irony about Tony. We managers spent a lot of practice time retrieving footballs that were kicked from the practice field into the “jungle” surrounding Waller Creek– and from the creek itself I caught poison ivy more than once.

So we were really glad when a young, enthusiastic kid came out every day and retrieved the balls for Tony. The kid was learning while he was watching. The “kid” was Billy Schott, who earned the nickname “Sure Shot” when he wound up as the placement specialist for DKR’s last two Cotton Bowl squads and a Gator Bowl team.

As a sophomore, he provided the winning margin as the ‘Horns upset

Joe Namath-led Alabama, 17-13, in the Gator Bowl (completing DKR’s record of never losing a game to Bear Bryant).

ROY A. JONES II

Senior Manager 1963

Tony Crosby

For most of his three years he spent on the Texas Longhorns varsity football team, the lack of a shoe on Tony Crosby’s right foot made as much news as the points it produced.

Rarely did a story that mentioned Crosby appear without use of one of the following adjectives: “shoeless,” “stockinged” or “barefoot.” Yet Crosby’s success as a placekicker was evident by the mere fact that, in 1962-63, stories were written about him – never mind the passing references usually accorded kickers in game stories.

“Well, I started kicking without a shoe in junior high (in Kountze) when I started formal football, but I remember when I started kicking in our front yard using crawfish mounds for a tee before that,” Crosby said during a recent email conversation. “A young man who worked for my dad set up a football and pulled off his shoe and kicked it. I tried it and never ever kicked a football with shoe on.”

His success reached its pinnacle in Crosby’s senior season, 1963, which happened to be the year the Longhorns won their first football national championship. Crosby was 24 of 24 kicking extra points and hit on 9 of 17 field-goal tries, setting or tying school records for each at the time; in addition, the points he scored in four key games provided the impetus for victory in those hard-fought contests: Arkansas (17-13), Rice (10-6), SMU (17-12) and Texas A&M (15-13).

“You know, we didn’t play many games on muddy fields,” Crosby said. “The most important exception was when the Aggies watered the field before the ’63 game such that we couldn’t kick extra points or field goals from the normal position, and I practiced kicking extra points from a hashmark. The field at the 10-yard line was so muddy that when the kicking tee was placed on the ground, it just disappeared in the slop. The game’s only field goal (a 27-yarder) was kicked from a hashmark and we didn’t kick the extra points.”

Crosby was the first Longhorn to letter in multiple seasons as a kicking specialist. As a sophomore, he did not earn a letter, having scored just 1 of Texas’ then-school-record 302 points in a 10-1 season in 1961 (that on an extra point in the season-opening 28-3 rout of California; he also missed four long-range field-goal attempts that season).

On the less-explosive (but still 9-1-1) Longhorns of 1962, Crosby was more productive, tallying 15 of 19 PATs in addition to 2 of 7 field-goal tries, including the game-winner in a 9-6 victory over Oklahoma. Crosby credits his improvement in ’63 to a staff decision to allow him to concentrate full-time on kicking.

“The difference was that that’s all I did in 1963 and other years I just worked out like everyone else [in 1961, for example, he is not listed as a kicker but instead as a backup end] and wasn’t able to practice kicking very much,” he said.

“Not any really stood out except perhaps the two against Tulane in the first game of the ’63 season and the field goal against Oklahoma in ’62. I do remember most of the kicks. I also remember the first kick I missed in ’63; it was against Rice when a Rice lineman grabbed Olen Underwood’s facemask and pulled him down so another Rice player ran through the gap and blocked the field-goal attempt. One extra point against Arkansas (in 1962) was memorable as Smokey the Cannon went off directly behind the goalposts as I was lined up to kick, rather than after the kick. Quite a shock!”

“‘Shock’ probably doesn’t sum up the emotion Crosby felt upon the Longhorns’ return to Austin as national champs the day after their 28-6 Cotton Bowl rout of Navy, in which Crosby kicked all four extra points on his 21st birthday. As recounted in the Jan. 3 Austin American:

“Dressed in a cream-colored leather jacket, sunglasses, dark slacks and two shoes, Crosby grinned and chatted and stood cheerfully signing note pad after pad offered by the youngsters.

“When a news photographer asked two pretty girls to plant kisses on the tanned and slightly reddening Crosby cheeks, the crowd cheered as happily as though the stocking-footed youngster had just kicked a 40-yard field goal.”

Those PATs against Navy were the final points Crosby scored in football. Instead, Crosby turned to academia, earning two bachelor’s degrees from UT – where he credits such influences as history professor Joe Frantz and architecture professor Roland Roessner – before returning there in the 1970s for his Masters’ degree in architecture. He parlayed that into a career in preservation architecture that he continues to pursue to this day; the email exchange took place days after Crosby, now 77, returned to Texas from a job in Egypt, where he does projects for New York University, Princeton University or New York’s Metropolitan Museum.

“I have worked in the preservation field since going back to school for my Masters’ in architecture in the early ’70s,” Crosby said. “I began to do some international work in the early ’80s and also taught internationally in Rome, France, and South America in the ’80s and ’90s. I did a lot of work on archeological sites in the states and South and Central America and began working in Egypt in 2000 because of my preservation work with adobe and earth buildings in general. The sites I have worked on in Egypt are all mud brick structures in various locations. I also worked and still work in California on adobe buildings and did quite a bit of consulting on the seismic strengthening of adobe buildings.”

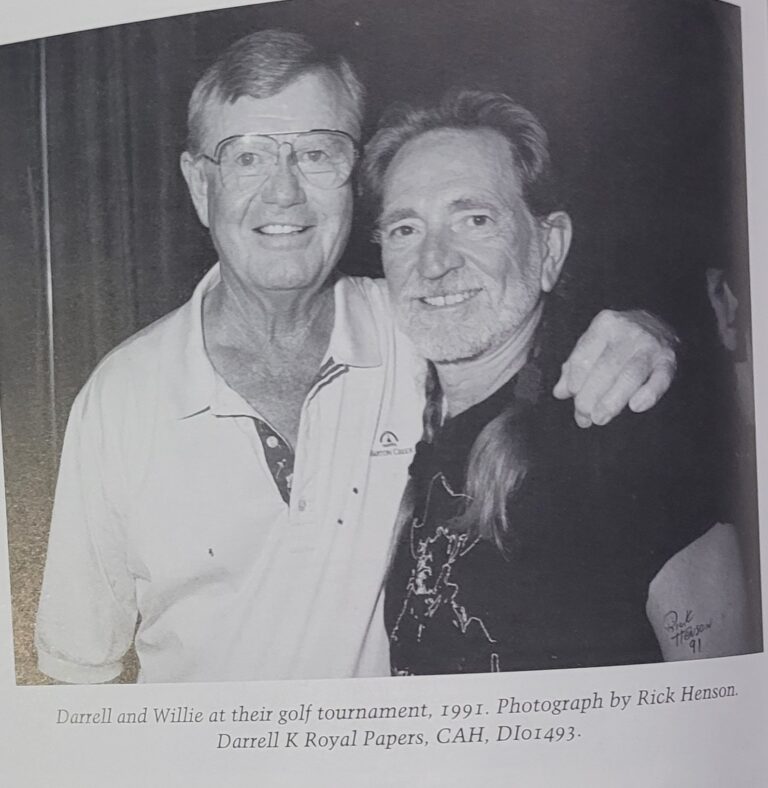

And, like countless other players who benefited from his guidance, Darrell Royal’s influence still sticks with Crosby.

“Two things Coach Royal said always come to mind that had a profound effect on me at the time and have stayed with me,” Crosby said. “One was after the Tulane game in 1963, the first game of the season, when we were in our dressing room. Coach closed the doors and didn’t allow the press in until he said this to us: “Boys, you didn’t play well tonight and when the press comes in you have a choice; you can complain about how terrible you played or you can make those Tulane players feel good about themselves by just talking about how well they played.” It was about validation – making someone else feel good about themselves. Such an important life lesson and I was struck by it even as a 21-year-old, and it has stuck with me and has been one of many guiding principles.

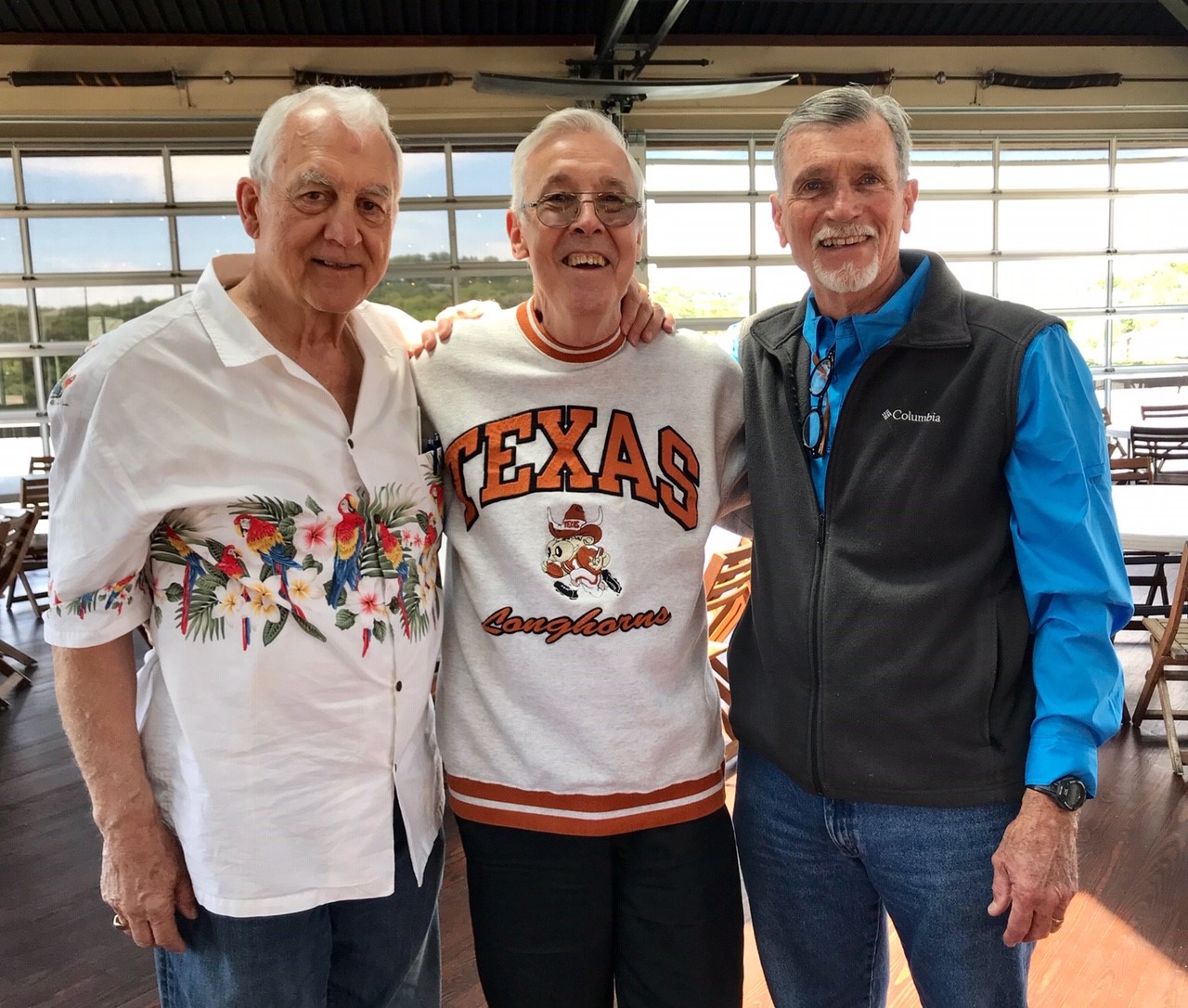

Tony with family and friends bonded by a shared experience.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1554321201841_55874 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid { margin-right: -20px; }

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1554321201841_55874 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid-slide .margin-wrapper { margin-right: 20px; margin-bottom: 20px; }

“The other was one of his humorous quips: ‘Boys, when you make a good play , don’t act like you’ve never done it before.’ Another important life lesson.

“Football is a team sport and you have to recognize the attributes and contributions of each member of the team and one thing I have done and am most proud of in my professional career is that I can put together a great team, rather than what I personally can do. And I have always been able to do that because I validate those people I come in contact with and then they will go out of their way to work with me.

“Validation can be a simple recognition such as a thank you.”

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX