Bill Little Articles Part VIII

Bill Little articles For https://texassports.com–

-

The Best that ever was

-

The National Championship 1963 (part I)

-

Texas Second Sport

-

Memories, Milestones, Hopes, Dream

-

The Return of the Horns

-

The Eternal Spring of Dick Tomey

-

Voice of the Longhorns’ passes away at 86

03.25.2014 | Bill Little Commentary

Bill Little commentary: The best that ever was

The diving well at the Lee and Joe Jamail Swimming Center is named for a former Longhorn who many consider the greatest diver of all time.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

When the nation’s finest collegiate men’s divers gather for the NCAA Swimming and Diving Championships at the Lee and Joe Jamail Swimming Center this weekend in Austin, they will be entering hallowed ground—or hallowed water, if you will.

That’s because the diving well at the center is named for a former Longhorn who many consider the greatest diver of all time, and who was as good in his sport as was any athlete in UT history.

David “Skippy” Browning was born in Boston in 1931 and started diving when he was four years old. By the time he got to the university in the late 1940s, he had entered his first competition as a diver at the age of ten. By the mid-1950s, he had won a dozen AAU and NCAA championships, and he had dominated the 1952 Olympics.

At the 1952 US Olympic Trials in New York, Browning won the competition by 100 points.

Browning, who moved with his family to Corpus Christi when he was three, grew up in Dallas and began competing under the tutelage of his father. Legend has it that he was turned down for an athletics scholarship at Texas and he started his collegiate journey at Wayne State in Michigan. That was before, so the story goes, that a rising young Texas supporter named Frank Erwin arranged for him to get a scholarship at UT. Browning transferred, and the rest became history.

In a time when NCAA diving was dominated by Ohio State, Browning became the nation’s hope to break the Buckeyes’ lock on the podium at the diving events. As a sophomore, he finished second by .06 points to Ohio State’s Bruce Harlan, and there began an unmatched rivalry between the two. At most meets, they swapped first and second place regularly, leaving the rest of the field behind.

Harlan edged Browning for a spot on the team and won the gold medal at the London Olympics in 1948, but by 1952, Browning had surpassed him. Judges called him “No Splash” because of what they termed his “phenomenal ability to knife into the water without a splash.” Others credited his remarkable ability to adjust a dive in the air to a peripheral vision that was so phenomenal that diving against him was “no contest.”

It was at 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki, Finland, that Browning won the admiration of the world with his amazing gold medal winning performance. Browning was so impressive, some who knew the sport well said that the sport-crazed Russians actually trained seven cameras on his every move to study him in an effort to emulate his success.

“They watched everything from how he prepared before a dive to how he toweled off afterwards,” said a former coach.

During his Texas career, Skippy was named All-American in 1950, 1951 and 1952. In all three years, he won the Southwest Conference diving championship on both the one-meter and three-meter boards. He dominated the sport as no other had ever done. He went undefeated in every SWC dual meet. Included in his success were eight AAU national diving titles and four NCAA titles.

In the spring of 1952 at the intercollegiate competition at Yale, he was given a perfect score of ten on a cutaway 1-1/2 pike, rated one of the most difficult of dives. He made up his own special dives and the AAU rules committee officially adopted some of them.

Popular on the campus because of his good nature as much as his athletics skills, he was named a “Goodfellow” by the Cactus Yearbook in both 1951 and 1952.

The 1950s, however, were way before endorsements made it lucrative to be an athlete. Skippy graduated from UT with a degree in business administration in January of 1953. By then, he was married (to Corinne (Cody) Couch; Sept. 7, 1950), and he chose to enter the U.S. Navy. He received his pilot’s wings as a Lt. JG in June of 1955.

In the spring of 1956, he was two weeks away from beginning his Olympic training for the Games in Melbourne, Australia. Stationed in California, he was on a cross country training flight in his AFJS Fury, an aircraft carrier jet. In a field near Rantoul, Kan., Browning died when the plane crashed. He was 25 years old.

As the world mourned his loss, accolades began to pour in. He was named to the Helms Athletic Foundation Hall of Fame in 1957. In 1960, he was inducted into the Longhorn Hall of Honor in a class that included Dana X. Bible, Jack Gray and Ernie Koy. He was named to the Texas Sports Hall of Fame in 1962.

In a medium that Skippy Browning could have only imagined, there are actually clips on the Internet of a few of Browning’s dives. There is no record of what happened to the film from the seven Russian cameras, but despite placing three divers in the top nine in the springboard, the Soviets did not win a medal.

What Skippy Browning proved so long ago was that diving is an art. In its own way, it is the freeform of humanity, twisting and turning in time so as to create the perfect entrance into the bright blue water.

And as the young men of this 21st Century mount the board for their flight, it is not only excellence that they are pursuing.

In the diving well at Texas, it is the memory, and the image, of perfection.

07.22.2013 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The 1963 National Championship (Part 1)

Texas Football’s quest for a National Championship followed a star-crossed path.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations Editor’s note: This season marks the 50th anniversary of Texas Football’s first National Championship. The following is the first part of an excerpt detailing that magical season from “Stadium Stories: Texas Longhorns” by Bill Little, published by Globe Pequot. You can read part two here.

It was battleship gray, the door to the old press box elevator in the west side of Memorial Stadium, and fewer than five of us had keys to the solid padlock which guarded the door.

The elevator was hand-operated, and it stopped at the ground floor and at two of the three levels of the long concrete structure which sat atop the single level stadium. The only entrance, other than the elevator, was a single door at the north end, which exited into the top row of the stands filled with wooden seats.

Except on game days, the door was barred from the inside.

On game days, the stadium buzzed with excitement. But if you had a key on a moonlit night and you wanted a place to show your date the stars and the lights of the city, you could ride that elevator up and no one, not Darrell Royal or God Almighty–and no one was sure they weren’t the same–could make it come down.

In other words, in the autumn of 1963, it seemed the safest place on earth.

That press box and the Tower were the tallest buildings on campus. There was no Jester Center, no LBJ Library.

The “Moonlight Tower” which stood on the northeast corner of the stadium cast a glow over the quirky baseball field across the street to the north, and over the wooden roof of the tennis courts which were located on the northwest corner of the stadium.

And on the field below, with a black cinder track surrounding it, a dream came true that fall, that fateful fall of 1963, when all of our lives would change, and nothing would ever seem safe again.

Texas’ quest for a national championship in college football had followed a star-crossed path. For years it seemed that the Longhorns and The University were riding on a great merry-go-round, and each time they reached for the gold ring, it somehow eluded them.

A couple of their Southwest Conference brethren — TCU in 1938 and Texas A&M in 1939 — had earned the honor in the years since the Associated Press first began its poll in 1936. A loss to the Longhorns in 1940 even knocked the Aggies out of a second title.

The 1941 team, which was featured on the cover of Life Magazine as the best team in college football, had fallen from contention with a late season tie and a loss.

Texas would produce top ten rankings four times in the eight year period from 1945 through 1952, but it wasn’t until Darrell Royal’s third team finished ranked No. 4 in 1959 that UT returned to the national landscape.

All that appeared to change in 1961. Royal’s first SWC championship club was a powerhouse. With an innovative offense called “the flip flop” because the offensive line and wingback would flip sides so as to simplify and maximize running plays, Texas steamrolled its opponents.

In a day of single platoon football, Royal effectively used three different teams, and most folks thought his third team backfield could play for anybody. The starting backfield featured all-American running back James Saxton, and Texas averaged over thirty points a game and yielded a scant fifty-nine points during the entire regular season.

On November 4, the Longhorns shut out SMU in Dallas, and the results of the weekend left Texas ranked No. 1 for the first time in twenty years. Two weeks later, however, the carousel of dreams would turn into a nightmare. In a stunning 6-0 shutout in Austin, a TCU team which would finish 2-4-1 in league play and 3-5-2 overall ended the quest. Texas would go on to win the first of Royal’s eleven Southwest Conference titles, and would beat Ole Miss in the Cotton Bowl. The 10-1 finish, the school’s best since 1947, netted a No. 3 national ranking

Texas was right back in the hunt in 1962. Despite the tragic death of a player due to heat exhaustion on first day of fall practice, the Longhorns opened with five straight victories. They were never ranked lower than No. 3, and by the Arkansas game on October 20, they had moved to No. 1. In one of the most dramatic games ever in the stadium in Austin, the Horns drove eighty yards to score the game’s only touchdown with thirty-six seconds remaining in a 7-3 victory over the No. 7 ranked Razorbacks. A defining goal-line stand, led by linebackers Pat Culpepper and Johnny Treadwell, had caused a fumble which Texas recovered midway through the third quarter.

A week later, everything would change.

It was an unreal feeling that night when Rice played Texas in Houston. There was a murmur in the crowd before the game, and the whispers were not about football. The humidity seemed to hang, as it can in Houston, and it almost seems there is a ghostly mist that hangs even now as the memory returns.

On the football field, Texas was No. 1. The Longhorns had made sure of that with that 7-3 comeback win over Arkansas the week before.

But there was an eerie reality that night in Rice Stadium, as 70,000 people stood, their hearts pounding a rhythm, and their voices raised in a powerful singing of the National Anthem.

Those who were there will tell you that until perhaps the patriotic swell which accompanied the events of 9/11 and the War in Iraq, they had never — before or since — heard the National Anthem sung so proudly and defiantly.

Since Tommy Ford plowed over for that winning touchdown in the Arkansas game, football euphoria had reigned in Austin.

Two days later, the real showdown came.

Early in October, when Texas was busy winning football games, the Soviet Union, under Nikita Kruschev, had moved 20,000 crack battle troops, forty intermediate ballistic missiles, and forty bombers capable of carrying nuclear warheads into Cuba, less than ninety miles from Florida.

On Monday, President Kennedy ordered a blockade of Cuba, and by the time Rice played Texas, the world had edged closer and closer to World War III.

Historians will say that it probably was — at least to our knowledge — the closest the world has come to nuclear war.

Four hundred thousand United States troops were on maximum alert. Weapons of war were loaded aboard ships and planes. Somehow, a football game that risked a No. 1 ranking didn’t seem important.

What was important, however, was a nation’s pride. That is why they sang.

The game itself might as well have been played in the Twilight Zone. Rice Stadium had always been a tough place for Texas to play before the recent domination, but that year was beyond comprehension.

No one gave the Owls much chance, but as would happen often with the Owls’ venerable coach Jess Neely, he had whipped “his boys” to a fever pitch to play Texas. The Longhorns never were able to get back up after the incredible “high” from the win over Arkansas. Texas trailed early, 7-0, but scored twice to make it 14-7.

Rice tied it, 14-14, and on a night when nobody appeared to want to be there, that’s the way it ended. Texas would go on to an unbeaten regular season and the nation’s No. 4 final ranking. Rice would finish the year at 2-6-2, but the tie kept the Longhorns from a national title.

The game was only a brief distraction from the fear of the greater conflict, a conflict that threatened life as we knew it.

But on Sunday — the next day — the Good Guys won.

The Soviet Union relented and began removing its troops and dismantling the missiles. President Kennedy gave the order for the United States Armed Forces to stand down. The danger of the missiles of October was over.

That, however, was only a harbinger of the mixture of fate that would manifest itself in the lives of the young men of Texas football in the early 1960s.

What 1961 and 1962 had done was create a strong winning tradition, and with an all-star cast, Royal and his staff were ready for 1963. The Horns began the season ranked No. 5. They moved to No. 4 the second week, No. 3 the third week and by the fourth week of the season, they were No. 2 as they headed for Dallas and the annual meeting with Oklahoma.

Since Royal’s first season of 1957, the Longhorns had not lost to the Sooners, but the national voters, the writers and the coaches, had installed No. 1-ranked Oklahoma as a favorite. Joe Don Looney, the Sooners’ star running back, had even challenged the biggest name on the Texas defense, Outland Trophy winner Scott Appleton, by saying, “Appleton’s tough, but he ain’t met the Big Red yet.” Neither, he would find, had he met Appleton.

The annual showdown in Dallas was the biggest game, but it came on a weekend of irony. The Friday night before UT and OU met, SMU knocked off the power of the East, Navy, and Heisman Trophy winner Roger Staubach, in the Cotton Bowl Stadium.

Then the next day, No. 2 met No. 1.

It was an execution of precision. With Carlisle operating the Royal Winged-T offense to perfection and the defense hammering the Sooners, Texas won 28-7. A sportswriter from St. Louis perhaps told the story best when he wrote in his lead, “Who’s No. 1? It is Texas, podner, and smile when you say that.”

Texas then began the improbable gauntlet of carrying the mantle of the nation’s No. 1 team for six long weeks. It made it through tough wins over Arkansas (17-13), Rice (10-6), SMU (17-12), Baylor (7-0), TCU (17-0) and Texas A&M (15-13).

The Baylor game, matching the unbeaten Horns against a Baylor team led by Don Trull and Lawrence Elkins, had been the best showdown in years in the Southwest Conference, with a Duke Carlisle interception of a late sure touchdown saving the Longhorns’ victory.

Texas beat TCU, 17-0, the next week, and looked forward to an open date on November 23 before finishing the regular season at Texas A&M.

Darrell Royal was standing in his bedroom, tying his tie, getting ready for the events of the afternoon.

It was Friday, Nov. 22.

03.07.2002 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Texas’ second sport

Jones Ramsey spent more than 20 years at Texas and another 10 at Texas A&,M and when he retired two decades ago, he left a legacy of work with the media. Ramsey, Bill Sansing and Wilbur Evans, along with able assistants such as Orland Sims, were the benchmark for those of us who worked with and followed them in the field called “sports information.” In fact, until the day he left, Ramsey would answer the phone simply, “sports news.”

It was in that capacity Jones walked and talked with the media of the day, which generally focused on a group called “the writers.” Electronic media consisted of a few television stations, a radio or so and ABC Television, which did an NCAA Football Game of the Week.

Web sites, talk radio and cable television were only dreams in the minds of those who would eventually create them. “The writers” covered football, paid a little attention to basketball, swarmed to the Texas Relays and covered more football. In the northwest corner of the Villa Capri Hotel, which ironically sat where Frank Denius Fields are today, was Room 2001.

It was there that head coach Darrell Royal would come after a home game to visit with the media and it was there that Ramsey entertained “the writers” with stories. Ramsey’s one-liners were famous.

It was probably there that Ramsey uttered his best-known one-liner concerning sports at Texas. Asked by a young reporter about some small bit of trivia concerning a Longhorns athlete in a spring sport, Ramsey replied, “son, there are only two sports at Texas: football and spring football.”

History does not record when he said it, but it lives in legend. Ramsey, who first went to college on a basketball scholarship, loves all sports. He was one of the most knowledgeable people in the track & field world (even though he also quipped “the only thing I hate worse than track is field”) and he can be seen, even today, sitting in his wheel chair beside his son Paul at Longhorns baseball games.

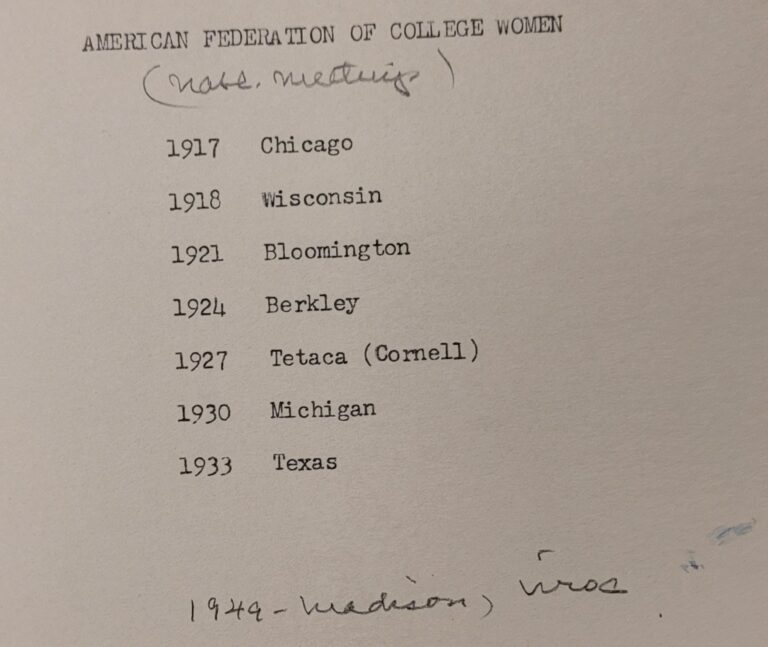

Since his utterance, basketball and the quest for the trip to the Final Four has become a national happening. Women’s sports, with Jody Conradt pioneering basketball’s popularity, have opened many doors and gained credibility throughout the country. All sports at Texas have grown and prospered. Men’s swimming coach Eddie Reese has won a eight National Championships. Rick Barnes, Augie Garrido, Bubba Thornton, John Fields and Michael Center continue to prove that men’s team sports are not only successful but nationally respected.

Eighty percent of the revenue for UT athletics is generated by football. Today, spring football is limited by NCAA regulations to 15 practice days over a 30-day period. Mack Brown has chosen to be the first team in the country to begin spring practice and that’s not because Ramsey would have expected no less.

As spring break begins next week, the Longhorns will be almost halfway through their practice sessions. Seven practices have been completed with seven more in addition to the annual spring game on March 30 to go when the team returns on Monday, March 18.

Brown’s philosophy is simple. Texas is a demanding academic institution. By conducting spring drills early, it gives the players a chance to concentrate on their classes and finals during the final two months of the semester without the distraction of having to practice. It also allows more time to heal any bumps and bruises and enjoy the Austin spring. In short, it allows student-athletes to be just students.

The Spring Jamboree, which will feature the Orange/White scrimmage on March 30, also will allow time to meet the players and collect autographs. Last year, more that 30,000 fans came and Brown and his staff are hoping for a lot more on this year. The price is right. It’s free and a pilgrimage that is becoming more and more popular in Austin.

The value of spring workouts come in the teaching. Those who come to scrimmages expecting to see polish won’t. UT is a work in progress and the 15 practice days in the spring are for instruction and learning. So if a pass is intercepted, don’t scream at the quarterback. Praise the defender. After all, this is the one time when you can cheer for both sides.

The work will be intense at times because competition can create that. The goals are to grow as individual so that your team will be better.

It is as coach Royal has said, “teams don’t quit, players do and if enough players quit, then the team loses. It works the other way, too. Teams win because players win.”

On a cold, cloudy day in spring 1963, a giant Longhorn named Scott Appleton stood on the sidelines watching a spring drill. Appleton took exception with an official, who failed to call something the big tackle thought should have been flagged against the offense.

“Come on,” Appleton yelled sternly at the ref and his teammates, “Get it right. We’re not out here for FUN!”

Games should be fun and that perhaps is why we play. But for this Texas team, the point is clear. The squad that finished ranked No. 5 in the country and ended its season with an 18-year best 11-2 record is looking to win two more football games. It is in the spring that the “second sport at Texas” lays its foundation for the fall. It is there that Brown and his staff see the effort from players who want to play like Appleton.

The record will show that in fall 1963, a few months after he was yelling at those officials as well as his teammates, Appleton received the highest honor available to a lineman when he won the Outland Trophy. It also was that fall when UT won all of its games and claimed the school’s first-ever National Championship.

So as this spring continues, cheer for all the Longhorns teams and celebrate their success and tip a Diet Dr Pepper to Jones Ramsey and remember that all games are a lot more fun when you win.

09.25.2008 | Football

Bill Little commentary: Memories, milestones, hopes, dreams

Sept. 25, 2008

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

In so many ways, Saturday’s Texas-Arkansas meeting is a classic example of everything that college football should be about. And in its own way, it is rare, because it brings the excitement of the present together with a proper recognition of history that is steeped in tradition.

On the one had, No. 7 Texas carries the flag of the Big 12 Conference into a match-up with old foe Arkansas, which now resides in the vaunted Southeastern Conference. The Longhorns are trying to finish their non-conference schedule with a perfect 4-0 record, and Arkansas is trying to see to it that they don’t.

That is all about the present.Mack Brown‘s Longhorns trying to play to a national standard, and new coach Bobby Petrino’s Razorbacks building their identity.

All of that is on the line Saturday in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium.

Then, there are the various salutes to history.

First, former all-American offensive tackle Jerry Sisemore will officially receive his on-campus salute for his induction several years ago into the National Football Foundation’s College Football Hall of Fame.

The weekend’s activities also will include a unique reunion of two vintage eras of Texas and Arkansas football. Planned by former UT quarterback James Street and his good friend and former team manager Bill Hall, the reunion weekend includes a salute to former coaches Frank Broyles of Arkansas and Darrell Royal of Texas, and the teams which played in the 1964 and 1969 games matching the two teams.

Because this year’s game had to be rescheduled in the aftermath of Hurricane Ike, the gathering has lost some of its folks who had conflicting plans when the two-week postponement came. But a dinner on Friday night will include members of the four teams, as well as Broyles and Royal. The two coaches are also expected to take part in the pre-game coin flip for the regionally televised (ABC-TV) game.

There is reason for celebration for both schools concerning those two seasons. Texas, of course, won the 1969 National Championship in the 100th year of college football in what was known as the “Game of the Century” in a 15-14 battle in Arkansas.

In 1964, things had gone in a different direction. Texas was No. 1 in the country when No. 8 Arkansas won, 14-13, snapping a 15-game Longhorn winning streak, and knocking the Longhorns out of a second straight National Championship. The Razorbacks would later be the beneficiary of the Longhorns’ work, however.

When Arkansas beat Nebraska in the Cotton Bowl game on the afternoon of January 1, the Razorbacks finished the season unbeaten. That evening in the Orange Bowl, in the first-ever night bowl game, Texas knocked off Alabama, 21-17. The Crimson Tide had already won the accepted National Championships awarded by The Associated Press and the Coaches Poll for United Press International, but the Longhorn win opened the door for Arkansas to grasp a small piece of the 1964 title, winning the awards given by the Football Writers of America and the Helms Foundation.

It remains the only national football title won by the Razorbacks.

While Royal and Broyles were great friends and held a unique place in college football in the Southwest, the Longhorns under Royal dominated the series. Royal’s Texas teams won 15 of the 20 games between the two during his career at UT from 1957 through 1976.

To complete the circle of history, the 1964 team will be featured Saturday when one of its finest players, linebacker Tommy Nobis, will be honored with the retirement of his No. 60 jersey.

Nobis, who won the Maxwell Award as the nation’s best football player following his senior season of 1965, is widely thought to be the best defensive Longhorn player of his era, and perhaps in Texas history.

Now an executive with the Atlanta Falcons, where he played professionally after leaving Texas, Nobis will be on hand and will be joined on the field by Alan Layne, the son of the late former Longhorn quarterback Bobby Layne, whose No. 22 jersey will also be retired.

The retirement of the jerseys of the two vintage Longhorns completes the current agenda for football jersey retirements under a plan announced this fall. Earlier, Vince Young’s No. 10 jersey was retired at the Longhorns’ season opener.

Later, basketball greats Slater Martin and Kevin Durant and baseball players Burt Hooton, Greg Swindell, Scott Bryant and Brooks Kieschnick will be honored.

In the midst of all of this, Texas and Arkansas will play the 77th game in a series which the Longhorns lead, 55-21. Originally scheduled as a home and home with a return trip next year to Fayetteville, the game was taken off the books by the Razorbacks, and is on hold for the foreseeable future.

With that, a series that dates all the way back to 1894 now goes dormant. With Arkansas beginning an annual series with Texas A&M in the Metroplex, both schools will likely look carefully at their non-conference schedules in the coming years before rebooking this one.

And so, as two young teams with hopes for the present and the future meet, it is particularly important to take a minute to salute the history of the games of the past, and those who played in them.

Darrell Royal and Frank Broyles are both in their 80s, and it is fitting that one more time, the two walk together on the green grass that is Joe Jamail Field at the stadium which shares Coach Royal’s name.

So too, is the overdue recognition of Sisemore’s induction into the College Hall of Fame.

But as we salute the late Bobby Layne and celebrate Tommy Nobis, eras of Texas football past are honored in a very special way. To be sure, you can make a case of other Longhorn greats whose numbers might one day join the three who this year were united with Earl Campbell and Ricky Williams in a special place of honor.

In his time, during the mid 1940s as a Longhorn, and carrying into the 1950s and 60s as a pro who was once recognized as “the toughest quarterback ever,” Bobby Layne carried the Texas banner to new heights in the years after World War II.

And Tommy Nobis had no peer as the best defender of his era from 1963 through 1965.

Memories and milestones of the past, hopes and dreams for today and tomorrow.

Collectively, they are all a huge part of college football.

And there will be no greater showcase of that than Saturday in Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium.

06.23.2014 | Bill Little Commentary

Bill Little Commentary: The return of the Horns

As the final curtain came down for 2014 Texas Baseball, eliminated from the CWS in the championship game of what was called “bracket one,” it wasn’t about what they had lost. It was about what they had won.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

As the final curtain came down for the 2014 Texas Longhorns, eliminated from the College World Series in the championship game of what was called “bracket one,” it wasn’t about what they had lost. It was about what they had won.

A team that came from nowhere in its own conference according to pre-season prognosticators left Omaha as the bronze trophy winner as the third place team in the tournament, forced from the CWS by Vanderbilt in a 10th inning that included the longest out and the shortest base hit in this year’s eight-team classic, 4-3. The Horns had beaten Vandy, 4-0, the day before to force the championship game. Saturday, they were only an out or a hit away from reaching their goal of playing Virginia for the National Championship in a best-of-three series that begins Monday.

They had fought to the last play, a weak ground ball with the bases loaded (which barely cleared the mound area sixty feet from home) that went for a base hit as a charging C. J Hinojosa somehow managed to actually turn it into a close play at first base.

In the top of the 10th, with the scored tied at three, Hinojosa had launched a deep drive to the wall in right center field. For a moment, it appeared that the Longhorns were about to take Augie Garrido to the CWS championship competition for an amazing fifth decade in a row. But a dramatic catch robbed them of that chance.

“I’m sorry I am late,” said Garrido as he sat down for the Longhorns’ final press conference following the game, “but I have 27 kids in there who have broken hearts, and I needed to talk to them.”

Tucked inside the visitors’ locker room, and later on a short ride back to the team hotel a couple of blocks away from TD Ameritrade Field, the team that everybody had come to love was crushed. They cried, not because they lost a game, but because there were no more games to play together.

This is the story of the 2014 Texas Longhorns.

It actually begins a year before, when the Longhorns had ended their season in last place in their conference. Nathan Thornhill had pitched Texas to victory that final day at TCU, and he stood in front of the dugout, talking in a radio interview about the future of the team, and how next year, “this team” would be better. It appeared, for all the world, that he had decided to try his hand at professional baseball.

As the media quizzed Garrido about the comparisons with the 1956 Longhorn team—the last time Texas had finished at the bottom, when the interview was over, he turned, and then said, “let me ask a question.

What happened the next year?”

Scouring the record books, the answer came and a call was placed to the Texas bus on its journey toward Austin.

“The answer to that question? They finished 20-7 and went to Omaha.”

“That,” said Garrido, “is what I wanted to hear.”

That was the beginning. Thornhill and leading hitter Mark Payton both chose to return to school for their senior year. Fall practice was rugged, as Texas shed the mantra of “We used to be Texas,” and set about restoring the program to its rightful place on the nation’s college baseball landscape.

To do it, each player had to buy in, to accept his role as a talented group of freshmen joined the returning upper classmen. Catcher Jacob Felts and first baseman Alex Silver maintained positive attitudes as freshmen supplanted them in the lineup. Madison Carter and Weston Hall, two junior college transfers who had played regularly in 2013, kept upbeat attitudes for the good of the team. Carter, in fact, stepped in midway through the conference season and became one of the squad’s leading hitters when opportunity came his way in a series at Texas Tech.

Perhaps it is trite to say they became a “band of brothers,” but that is what they did. An outfield that included Payton, raw but highly talented Ben Johnson and emerging junior Colin Shaw became “the sharks” who ran down almost everything in the outfield.

Second baseman Brooks Marlow was so good defensively he earned a Rawlings Gold Glove, and shortstop Hinojosa blossomed to merely spectacular by the NCAA playoffs. The final pieces of the puzzle came from three true freshmen, in catcher Tres Barrera, third baseman Zane Gurwitz, and first baseman Kacy Clemens.

The batting order shifted from time to time, but the core of the nine position players and the DH role remained the same for most of the season.

If the outfielders were the sharks, the infielders and Barrera were the “bandits,” robbing opponents time after time. And the pitching staff was the “tip of the spear.”

Dillon Peters, Parker French and Thornhill started the rotation, with Lukas Schiraldi a steady hand as a starter in the midweek games. Ty Marlow, who was in competition to be the team’s closer, went down with injury at the beginning of the season, forcing pitching coach Skip Johnson to recreate the role in a rotation that included everybody from Thornhill to a rehabilitated John Curtiss.

When an elbow injury ended Peters’ season at the end of Big 12 competition, Chad Hollingsworth moved from the bullpen duties he had shared in middle inning relief with freshman Morgan Cooper, and lefthanders Travis Duke and Ty Culbreth to become a starter. Pitching brilliantly in that role in the NCAA regional and the CWS, he quickly became another emerging star.

Meanwhile, Garrido and his staff of full-time assistants Skip Johnson and Tommy Nicholson, volunteer coach Ryan Russ and the rest of the support staff had settled into their second year together with tremendous stability both on the coaching and the recruiting fronts.

From the time youngsters first pick up a bat and toss a ball, baseball often seems destined to be a team game made up of individual interests. This remarkable team checked its egos at the door. That is how, game after game, a different player always seemed to shine. Payton’s amazing streak of reaching base 101 times certainly contributed mightily, but up and down the lineup, back and forth from the mound and the bullpen, stars seemed to align together.

Folks came to love this team for its spirit. It was never perfect, but it was perfect in its imperfection. Most of all, it had heart. From bullpen catchers such as Grant Martin and James Barton to the student managers and trainers and staff, this became a team with a common purpose. More than winning itself, it bought in and went all in for the purpose of team, togetherness, and an innate love of the game.

In an age where teams seem to be like sky rockets—blazing to the top and then fading—Texas has remained the constant. Its 35 College World Series appearances far exceeds its next closest competitor for the “most ever”—Miami with 23. The third place finish marks the 27th time Texas has finished in the Final Four in the CWS. Texas has played in a dozen championships games, finishing first six times and second six. As the legendary dynasties have fallen away in a scholarship-challenged environment (with only 11.7 scholarships in baseball) which seems to mandate parity, the Longhorns live in a world where missing Omaha for a couple of years is considered an upset of major proportions.

It should not be lost that Garrido in the postgame press conference said he thought that this 2014 team was the best Texas team since its 2005 National Champion. That is not to dismiss the 2009 runners-up, or the 2010 team which was knocked out as the nation’s No. 1 seed in a Super Regional in Austin.

In the formative years of the lives of the current college freshmen, Huston Street was pitching Texas to the CWS championship when they were six and seven. By the time they were ten and eleven, Texas was winning the series again in 2005.

All of that we know. What we also know is that the spirit and tradition of Texas baseball, which this team has restored, is one of continuity. This is a team which has done things right, on the field, in the classroom, and in the community.

Success is contagious, and it expected. In the early 2000s, Texas was a base hit away from beating Stanford in 2001 that would have meant the Longhorns under Garrido were in Omaha six straight years from 2000 through 2005. History has a pattern there. Cliff Gustafson’s team appeared here every season but one from 1968 through 1975, and again from 1979 through 1985. That’s not coincidence; it is the result of a built-in marketing bonanza.

So how do you win even when you lose?

Garrido has said that the 10 days of the College World Series is a “life-changing experience.” It is that because the purpose of a university is to educate, and there are no greater life lessons than those learned in the arena of competition. You understand about working together, you understand that there are wins and losses, joys and pains, and with each lesson learned comes an opportunity to grow.

The pain of loss is lasting in that you remember how it feels, and never want to feel that again. That is one of the many aspects of Omaha, but if to learn it you have to experience it, the next best thing you can do is “pass it on.” Each player, each person, has been particularly touched. And they depart with one common purpose: to get back to this city in the heart of America’s Midlands, where the boys of summer play and folks dream big dreams.

That was the challenge that Nathan, Mark, Jacob Felts and Alex Silver were faced with. Because they were freshmen in 2011, they were the only ones who could tell the stories of what it was like to walk on the field at TD Ameritrade, grab a burger or a pizza in the Old Market, get treated by their parents to a steak at one of the city’s legendary restaurants, or cross the Missouri on the pedestrian bridge to Iowa. Now, there is a new set of stories, a new collection of memories.

The most exciting part of all is that the Longhorns will return almost all of this team of 2014, including several young players who are waiting in the wings from last year’s freshman class.

Texas also expects most (if not all) of its talented recruiting class to be in school in the fall. In other words, the foundation is firm. Always positive, Garrido doesn’t live in the past; he respects it. He honors the present appropriately, and looks forward to the future.

The pain of the final loss will take a while. There is nothing more painful in sport than to be left standing in the field, with no chance to come back, no chance for one more at bat in a sport where you didn’t run out of time, you simply ran out of innings.

Time will accord these 2014 Longhorns their rightful place in history. The joy they brought will sustain. You loved their effort, you loved their fight. You marveled at some of the things they did, and you were chagrined at others. In the growing-up world of Omaha, sport really does mirror life.

Most of all, we will remember how they bonded together, fought for each other, playing a kids game with a stick and a ball. And in that space, what mattered most to all of us was the greatest gift they gave us.

They played with all their hearts. And you can’t ask anything more than that.

03.05.2014 | Bill Little Commentary

3.05.2004 | Football

Bill Little commentary: The eternal spring of Dick Tomey

He is a man of the Islands, this ageless wonder named Dick Tomey. But his love of the game and the kids who play it has brought him back to football, and his loyalty to, and belief in his friend Mack Brown has drawn him to The University of Texas.

Dick Tomey holds a rare distinction. He is the winningest coach in the history of two different universities. He is universally respected as a coach and as a mentor, a father figure whose players fought for him, and cried for him.

His adopted home sits in the Kahala area on the Hawaiian Island of Oahu, a place where the sun and the sand and the sea converge. It is there that morning rainbows dance across the sky after a gentle shower, and seemingly disappear into deep blue waters of the Pacific. Those who know him will tell you that the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow is actually Dick Tomey’s heart.

The image fits. But make no mistake about it: there is a firmness and toughness in the discipline of Dick Tomey. He will alternately drive you and hug you, and the legion of guys who have played for him love him for it.

He has the wisdom of your grandfather, yet the energy and enthusiasm of your buddy. Best said, he is a man for all ages.

Dick Tomey never intended to be a college football coach.

“I am one of those people who always loved athletics, and I admired a high school coach of mine,” he says. “I admired his lifestyle. When I got into coaching, I got into it with the idea of being an assistant high school coach and coaching all sports (football, basketball, baseball) because I thought he had a great life, and I admired him personally.”

Ironically, it was the sport of baseball that started Dick Tomey’s odyssey to the space where he is the new assistant head coach for defense and defensive ends coach at Texas. As a collegian, the native of Bloomington, Ind., led the Division III DePauw Tigers in hitting with a .333 average in 1958. Long after his collegiate playing days, his love affair with baseball has never waned.

In his years at Tucson as the head coach of the Arizona Wildcats, Tomey continued to play city league baseball.

“When I was 55 years old I played all nine positions and was the starting pitcher and got the save. I played until I was 64, and am hoping to play here,” he said.

But it is to the game of football that Dick Tomey has dedicated his life. Entering his 41st season as a coach, he still is enchanted with the game and the folks who play it. He bounces around practice with his cap on backwards, and his pervasive enthusiasm transfers easily to his players.

“To me,” he says, “the most compelling thing about the game is the relationship of coaches and players. Football is not fun to practice. It is not fun to work in the off-season. Most other games, baseball, basketball and golf, are fun to practice. A person gives so much, but he also gets so much out of it.

“It is not a complicated game. People are complicated, and it takes so many more people to play football than it does any other game. People play such distinct roles. There is so much difference in a right guard and a wide receiver and a corner back and a defensive tackle. Personally, there is so much difference, and yet you have to put all these hearts and minds together and make a team that’s unselfish and pursuing common goals. There are just so many different responsibilities and roles guys play. It makes it a fascinating management problem, and a fascinating problem to try to keep everybody going in the same direction.”

Tomey’s roots in the game were nurtured from the outset.

“When I got out of college, I went into the insurance business for like, three days. I hated it. They were starting to tell you what kind of shoes to wear, what kind of tie to wear, and, I wanted to be outside, and I wanted to be with kids.

“So I got a coaching job at a junior high coaching football, basketball and girls and boys track. One of the kids I was coaching had a dad who was an assistant coach at Butler University. He suggested I ought to look into becoming a college coach. So I did.”

Tomey picked the best school in the business for creating coaches, and was fortunate to get the only graduate assistantship they had. And it was there that he began an association with coaches that would read like a “Who’s who” in the profession. Halfway through his first year, Bo Schembechler became the head coach.

Coaching experiences at Northern Illinois and Davidson led him to Kansas, where he was part of a remarkable staff assembled by Pepper Rodgers. With co-workers such as John Cooper and Terry Donahue, Tomey made his first of 10 bowl trips when the Jayhawks won the Big 8 and represented the league in the Orange Bowl against Penn State after the 1968 season.

When Rodgers took the job at UCLA in 1971, Tomey joined Donahue as part of his original staff. Tomey stayed through the two-year tenure of Dick Vermeil and for Donahue’s first season of 1976.

“Then I got an opportunity,” Tomey said. “We had been on vacation many times in Hawaii, and I had a fascination with the Islands. A UCLA guy named Ray Nagle, was the Athletics Director, and J. D. Morgan (UCLA’s AD) thought he could help me. Everybody else turned the job down, and I got it. It was the greatest thing that ever happened to me, because Hawaii has now become home. I didn’t grow up there, I wasn’t born there, it just feels like home.”

And so, in the shadow of Diamond Head in the land between the sea and the mountains, Dick Tomey put down his roots. And in 10 seasons there, he took the program into Division I football and became the winningest head coach in the school’s history.

“It was a marvelous experience,” says Tomey. “When I got a chance to go to Arizona, I cried like a baby. I accepted the job, and when I went back and saw the players, I darned near decided not to go. I’d been there 10 years, and there was a big piece of me there. But I realized that if I was ever wanted to go some place, Arizona was about as good an opportunity as I was going to get.”

The love affair between Dick Tomey and the University of Arizona was a perfect fit. He took his teams to seven bowl games in 14 years, and he carved a 95-64-4 record competing in the tough Pac 10 Conference. He earned immense respect on the field and in the community. In 1999, he was awarded the Provost Award as Arizona’s Outstanding Teacher — the only coach in history to be so honored by the faculty. A year later, he resigned under pressure.

“It wasn’t the way I wanted it to end,” he said. “But it was the best thing that ever happened to me, and the worst. The powers that be wanted us gone, but the good thing about it was the outpouring of support from the team and the community. I never got so much mail or so many phone calls. My eyes were wet for two weeks because people just kept coming by, players kept coming by, so that was the best thing that ever happened. Leaving was painful, because I wasn’t ready to leave.”

But always the optimist, Tomey turned the negative into a positive.

“The opportunity I got,” he said, “was to go back to Hawaii and get involved in some television and very involved in their program. My son worked for the Arizona Diamondbacks, and ironically that fall, they were in the World Series. Rich calls and says ‘Dad, I get to go, and I get to take somebody. Let’s go.'”

The autumn of a football coach does not include time to watch the showcase of professional baseball, but it was a perfect fit for a guy hanging out on the outskirts of Honolulu.

Tomey followed that with a trip to Canada to watch the making of a movie based on one of his wife, Nanci Kincaid’s, novels.

“We got to do a lot of things,” he said, “and we’d go for a lot of walks and watch a lot of sunsets. The two years I was out of coaching were terrific. But I always thought I would get another head coaching job, and I would like to get back in a position where I thought I could really help a program that I believed in.”

The cast of characters running the San Francisco 49ers provided the first opportunity, as he was reunited with friends such as Donahue and Bill Walsh and Dennis Erickson. There, he coached the nickel backs on the 49ers defense.

“I was excited about the opportunity to work with the 49ers, because I had never done that before. All of the people there I knew and respected, and it was a marvelous experience with the players, as well as the chance to live in the San Francisco area.”

Then one morning, the phone rang, and it was his good friend Mack Brown.

“When Mack approached me with this opportunity, I was thrilled because I had been here several times at his clinic and a couple of years ago I spent some time with his coaching staff. I had had a chance to see first hand where Texas was. I am here because I believe in Mack Brown, and I believe in the kind of program he’s trying to develop, and hopefully I can be helpful.

“I am very, very fortunate in terms of the people I have been associated with, and I am more than fortunate to be here.”

And what is it, when it is all said and done, that keeps this silver-haired guy running with the kids?

“What keeps me young? I don’t know. I’m in good health. I enjoy sports, I enjoy working out, and I’ve always been an optimist. I enjoy a lot of things — movies, politics, the world situation. Nanci is such a wonderful person she has helped me be more multi-dimensional.

“On our first date, we went to the art museum, the Kennedy Library and a Boston Red Sox game at Fenway Park. A perfect day, although she says I surprised her with the museum. What I know is, if your outlook stays young, you have a chance to stay young.”

Bill Little commentary: Remembering Wally Pryor

‘Voice of the Longhorns’ passes away at 86.

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

For many, of an era that has passed, what will they will remember most about Wally Pryor will be a voice over the public address system — somewhere, some place. More significant, however, was the man behind the microphone.

Because, you see, as good as he was at speaking in public, it was with his heart that he spoke the loudest.

The record says that Wally was 86 years old when he died, troubled by a long battle with memory loss and the ravages of aging. But we never really knew whether that was true. Wally, you see, was a “leap year” baby, born on February 29. So he could only celebrate his birthday every four years. Perhaps that was the reason, during his many active years in Austin and around The University, that he seemed so forever young. Once, at a UT men’s basketball game in the early 1990s, the crowd serenaded Wally as he celebrated his “16th” birthday. It was, of course, on February 29.

His long association with football at what was then known as Texas Memorial Stadium began in the late 1950s, soon after the arrival for the 1957 season of an energetic new football coach named Darrell Royal. Even before that, however, Wally was busy volunteering his time, working for UT Athletics. He had been a swimming letterman in the late 1940s, and in the early part of the 1950s, he helped organized an event known as the Aqua Carnival at UT. He soon became the number one ambassador for all things Texas, but always in a behind-the-scenes role.

From his place in the production studios at KTBC-TV, he masterminded the original format of Royal’s weekly TV show. It was Wally who first used “Wabash Cannon Ball” as the show’s theme, creating an icon for the Longhorn Band that would become synonymous with Royal and the Show Band of the Southwest throughout his head-coaching career from 1957-76.

While his brother, Cactus Pryor, became famous as a humorist and a popular after dinner speaker throughout the country, Wally’s gifts were focused primarily on Austin and The University. When the first meeting of a committee to establish the Longhorn Hall of Honor was held in 1957, Wally was there. When the Texas Exes needed video for their Distinguished Alumnus Awards, Wally teamed with another local talent, Gordon Wilkison, to create the films.

When the Longhorn football banquet celebrated National Championships in 1963, 1969 and 1970, it was Wally who produced it. And it would be Wally’s voice you heard with special announcements — always, always off stage, away from the limelight.

For years, if there was a charity event, a rodeo, a fund raiser, or just a community celebration in or around the Capital City, Wally was at the microphone. Most of all, Wally would forever be linked as the voice of the Longhorns when it came to the football stadium or the basketball gymnasium. If there was a game, there was Wally.

In 1977, he made the transition with the Longhorns from historic Gregory Gymnasium, where Wally once swam as a fine water polo player in the pool beyond the stage, to the Special Events Center (now known as the Frank C. Erwin Center). He was courtside in 1979 when Abe Lemons confronted Arkansas’ Eddie Sutton on the court at halftime of a crucial Southwest Conference game. He playfully announced the arrival of UT’s first basketball dance team, known as the “Longhorn Luvs.” In his own way, he was every bit the showman that Cactus was, only as far as Wally was concerned, he was never the star.

He kept that place for the players and the coaches whose story he told.

When Jody Conradt was first getting the UT women’s program on a roll toward its 1986 National Championship season, Wally would retire after the game to the Fast Break Club, where the “Lady Longhorns” as they were called at the time would join adoring fans. Around Christmas time, Wally would coax the players on stage for a rousing basketball slanted take off on “The 12 Days of Christmas.” Complete with Santa hats, he had a hoops line for each verse such as “Five SWC Championship rings.”

Still his greatest legacy was the public address at the stadium, along with his relationship as the announcer for the Longhorn Band. For 40 years, he manned the mike, covering an era from Royal to Ricky Williams. It was a different time in sports, a time before structured scripts dictated every moment in the public address booth. Wally loved freelancing, and in a space where he had a captive audience of 65,000 people, he owned the microphone.

There, he could tell his friend, Hondo Crouch, that he needed to pick up his grandmother at some local drinking establishment, or delight the crowd with his weekly announcement of the score from tiny Slippery Rock College in Pennsylvania. In the early 1960s, when there appeared to be a confrontation between the Silver Spurs who were walking Bevo around the track into the midst of the Texas A&M yell leaders, Wally announced in his usual dead-pan style, “That’s a cow, Aggies.”

Most famous, of course, was his effort at crowd control after Texas’ upset of nationally-ranked Houston in 1990. On one of the rare occasions where Texas fans actually were moved to rush the field, a group surrounded one of the goal posts as the game ended, with one appearing to climb up the standard. It was then that Wally famously uttered, “Get that idiot off the goal post!”

By the end of that decade, however, things had begun to change. Marketing and a search for new revenue sources changed Wally’s role, and the structure soon became frustrating. Electronic scoreboards and ribbon boards brought the scores into the stadium that Wally had delighted in announcing. Sometimes, with an unintentional gaff included.

Basketball PA announcing at most games had followed the lead of the NBA, with shouting, bells and whistles. Wally by then had realized that his folksy style didn’t fit. After the 1999 season, with the changing times at the stadium, it had become harder and harder for Wally to enjoy. With the end of the 20th century, the guy who had been involved in UT Athletics for almost half of it, decided it was time to leave.

Veteran Austin radio personality Bob Cole was asked to handle the announcing with the Longhorn Band, and for the last 14 seasons has been a part of the PA presentation at Longhorns home games.

Alzeheimer’s disease robbed both Wally and Cactus of memories of current events before Cactus died in 2011 and Wally’s passing on Saturday. But for those whose lives they touched, they gave us all something to treasure.

In Cactus’ case, it was that of a legendary pioneer in broadcasting and public speaking. Wally, however, leaves with something else.

He touched a part of us that nurtured the soul from our youth to the gray hair and measured step that comes with the turning of the years. Wally was unique. He was never perfect, and he could laugh at himself. In fact, you never laughed at Wally, you laughed with him. Most of all, he was fun. We will remember the kisses on the cheek and the hugs for the pretty girls, the handshakes and smiles for the guys.

He was a part of the tapestry of UT Athletics — a voice now silenced, but a life well lived.