Ted Gorski by Jim Bayless

TED Gorski’s Eulogy By Jim Bayless

Tina, Susanna and James, it is an honor to be with you and Ted’s former teammates, protégés, doubles partners, flummoxed opponents and other friends at this time and place. It makes me smile to remember and celebrate his life and his considerable impact on many, not least me.

When you’re a kid and the tennis bug has bitten you, you look up not only to the champions of the world but also to college players closer to home—and all the better if they play for the University of Texas.

If you work hard enough at it and measure up, you dream of becoming one of them yourself one day. (I see a lot of knowing looks in the congregation.)

For me at age 14, the UT tennis team of the mid-’60s, which included David Nelson; Bill Driscoll and Jim Langdon, who are here; Leo Laborde; and others, was Exhibit A: terrific players who also looked the part—clean-cut and sinewy, with Coach Wilmer Allison-mandated “athletic haircuts and no facial hair,” as his Freshman Instructions memo read, and with shirttails always tucked in.

But it wasn’t just their skill on the court that was striking. In the coming years, I would learn they were blood brothers off the court, too, with a camaraderie that would endure for life.

In fact, there may not be another sport at another university with the “glue” that characterizes Longhorn tennis, a trait that Coach Allison instilled, as Dr. Penick had before him.

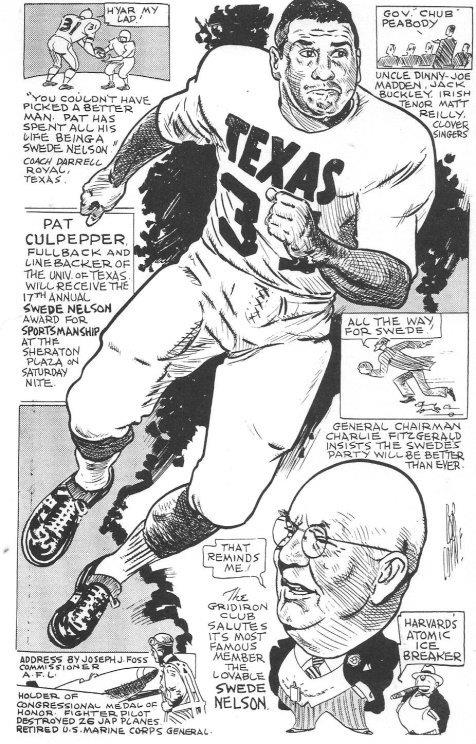

The leader of that pack was Ted. I saw him play for the first time in the Austin Labor Day tournament at Caswell Tennis Center a few months after he had won the Southwest Conference singles championship in 1966, upsetting Butch Seewagen and John Pickens, two Rice Owls with top national standing.

This accomplishment was spectacular. In his first year, he had been the low man on the totem pole on the freshman team. (Freshmen couldn’t play varsity at that time.)

Wilmer took a chance by keeping him on the squad; he vaulted up to second-to-last the following year.

When he won the Conference singles title his junior year, Wilmer, a father figure to Ted, told him, “Well, I just knew you were a late bloomer.”

Four years later, as UT freshmen, Dan Nelson and I heard much more from Ted (as had Marc Wiegand over the previous two years), then in his final year of law school and moonlighting as Wilmer’s assistant coach.

He had a dedicated work ethic and studied relentlessly. (Later, as assistant city attorney, he was at the office every day no later than 7:00 a.m.)

Ted was never at a loss for words, funny, and always with a quotable quip at the ready. (After popping in his contact lenses, he would declare himself a “man of vision.”)

His humor often carried a long needle, and no one was exempt.

He taught us a lot about the game the hard way; we rookies couldn’t take a set off him.

Ted had the world’s fastest bullwhip service motion and a piercing forehand volley he called his “harpoon shot.” He always barreled in, taking the net. “Charge the barrier!” he instructed.

Ted, who never owned a car until he was well out of law school, was then serving in the US Coast Guard Reserves.

To complement Tommy’s remarks, here’s the “Paul Harvey, rest of the story”: Ted had me be on call at dawn on Saturday mornings to drive him to the feeder road on I-35 to hitchhike to Fort Worth for his periodic meetings with “the Coasties.” (An odd military branch for him, given his propensity to get seasick every time he was on the water.)

He carried an enormous poster with “Fort Worth” written in Marks-A-Lot on one side and “Austin” on the other. Remarkably, he rarely had to wait long for a free ride door to door.

I’d ask how the session went when he returned on Sunday evenings. “Just another selfless act of protecting our shores from foreign oppressors,” he answered.

Ever since my early role as slave labor, Ted took me under his wing as a big brother well after we both had left Austin.

During my three years of law school in Dallas, I invited myself to spend practically every weekend in Ft. Worth with Ted and Tina.

The usual cast for doubles was Ted, Dr. Brown—always Dr. Brown—Willy Wolfe, Walter Williams, Tommy Roberts, or Doug Crawford (“Farah,” as in Fawcett, as Ted dubbed him, given his billowing blond locks), either at McLeland Tennis Center or elsewhere.

To help me relieve the tedium of law school and for our mutual mental health, Ted would agree to sneak away from the City Attorney’s office at midday for a different kind of “court appearance” for Ted, no matter how blazing hot or freezing cold it might be.

And that pattern didn’t stop for the next three decades I was in Washington. Chez Gorski always had an open door whenever I’d come to town.

The Gorski household was always a bit of a sitcom, with four extroverts holding forth at once, all on “Transmit,” none on “Receive.”

Ted was almost always playing defense. He had to sleep with one eye open as if he were Peter Sellers as Inspector Clouseau in The Pink Panther series, about to be jumped by Kato, his Chinese manservant.

When Susanna and James were young, he would observe, with “loving” exasperation, “To my kids, instant gratification doesn’t come soon enough.”

Ted was equally at risk with Tina, even on his birthdays, which you’d think would be safe harbors for the honoree.

I once had taken a picture of Ted as a spent force, lying prostrate on the court and pallid on a thermometer-melting day. The following year, Tina naturally used that same photo as the invitation to his upcoming round-numbered birthday.

To redeem herself (well, partially), the invitation she sent to his next round-numbered birthday party was a photoshopped Ted holding the Wimbledon singles trophy aloft.

The hospitality wasn’t always one-way. Ted showed up for Liz’s and my wedding in Washington three days ahead of schedule. You see, he and Tina were moving houses at that very time, and he sought to get out of as much blue-collar duty as he could.

Later on, they sent my goddaughter Susanna and James for stints in Washington, if only to try to even the score on free meals and entertainment provided.

Susanna’s timing of her fall internship in Congresswoman Kay Granger’s office could have stood improvement, though. It started (and could have ended) on that fateful day of September 11, 2001. Liz and I rescued Susanna from her Capitol Hill dorm to dine and bunk with us instead.

* * * * * *

My blood-brother friendship with Ted has been a rich and rewarding blessing for over half a century, from Penick Courts to Gorski guestrooms to member-guest tournaments to vacations from Hawaii to Bermuda. I will cherish the memories, always with a smile and a laugh.

Thank you, Tina, Susanna and James, for allowing me to speak as we celebrate Ted’s abundant and giving life. It is now game, set and match, Mr. Gorski, as he hoists the championship trophy on Center Court, this time for real.

End of Article