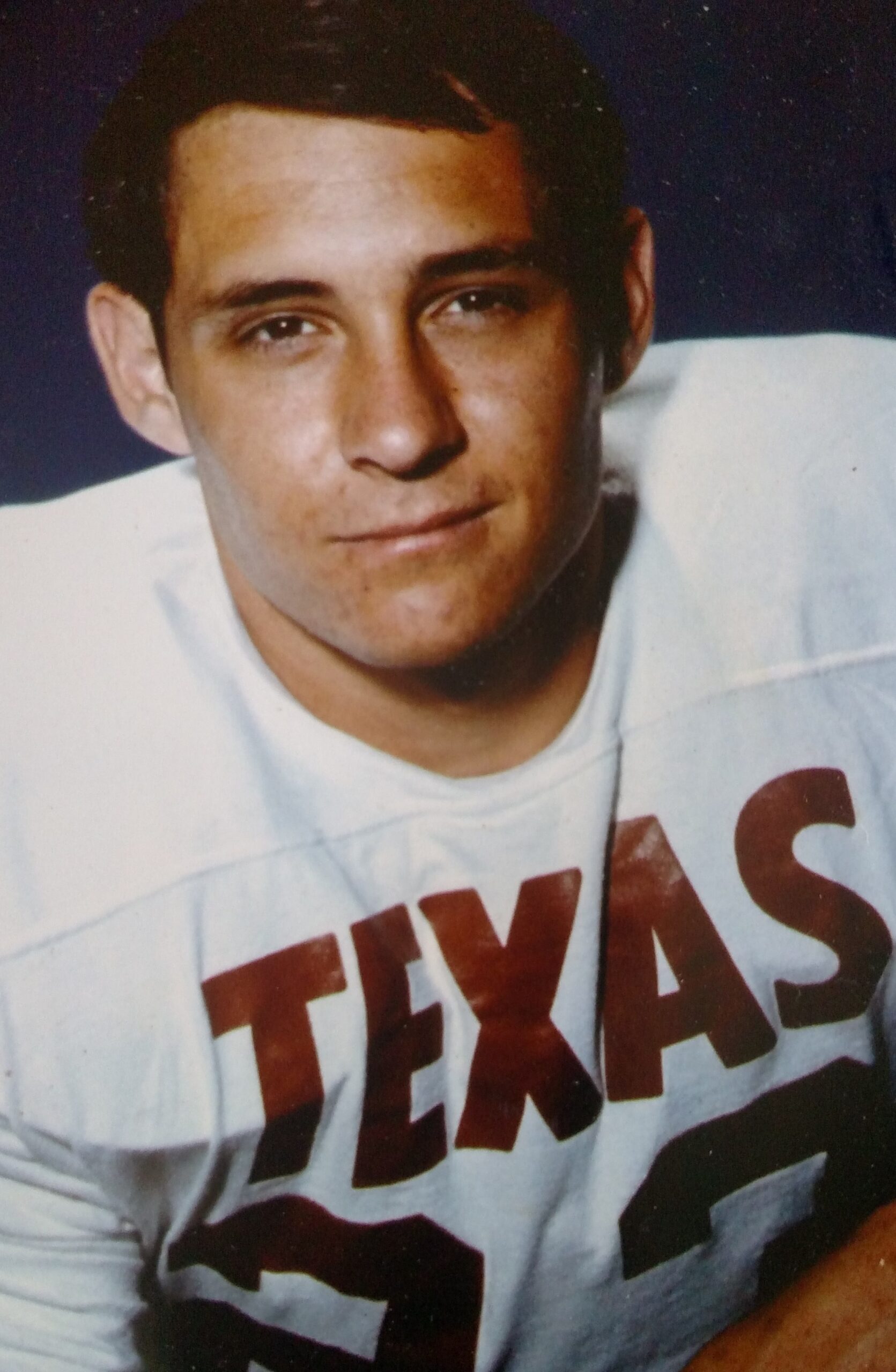

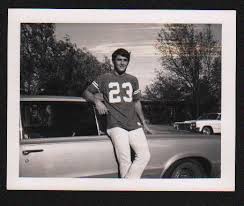

Danny Lester

A story by Cotton Speyer about Danny Lester

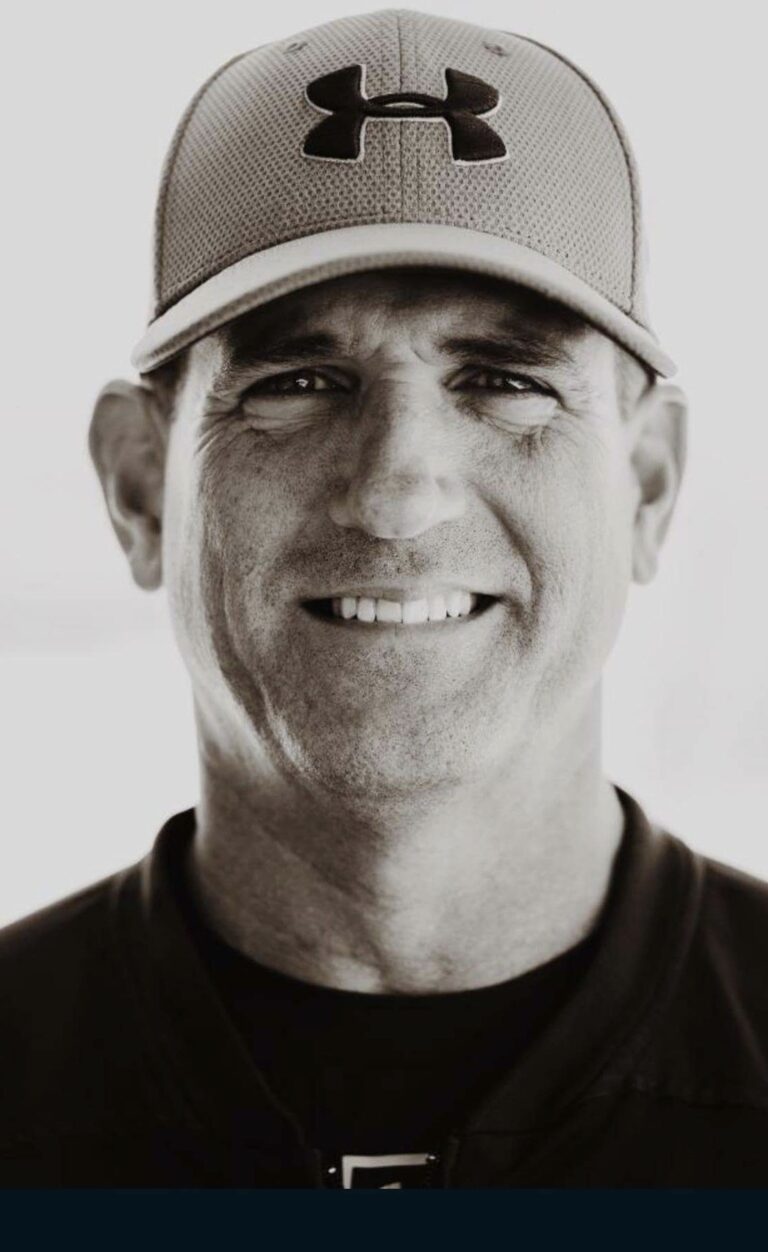

While communing with a small group of friends recently, I asked the birth date of a mutual friend that was coming up in late June. June 23 was the answer. Ok I said, “June – Danny Lester”, I’ll now always remember the date on June 23. Huh? was the unspoken look on their faces. I remember birth dates by using jersey numbers I said, and Danny Lester wore number 23. You’ve never heard of Michael Jordan or Lebron James someone incredulously asked, both number 23? So who is Danny Lester? The crowd, UT fans so they say, is a bit younger than me and obviously not up on vintage UT football. Danny Lester was a great athlete and football player on UT teams that won 30 games in a row I said, informing the grossly uninformed, and the best 23 in my book. Danny was quiet, gracious and one of the nicest people one could ever meet; look him up I told them. Was? someone asked. Yes, we lost Danny in his early 20s; car wreck.

Here’s To You Danny! Your Teammates Love You And Will Never Forget You, Nor Will Any UT Fan, Or Otherwise, That Was Graced To See You Play.

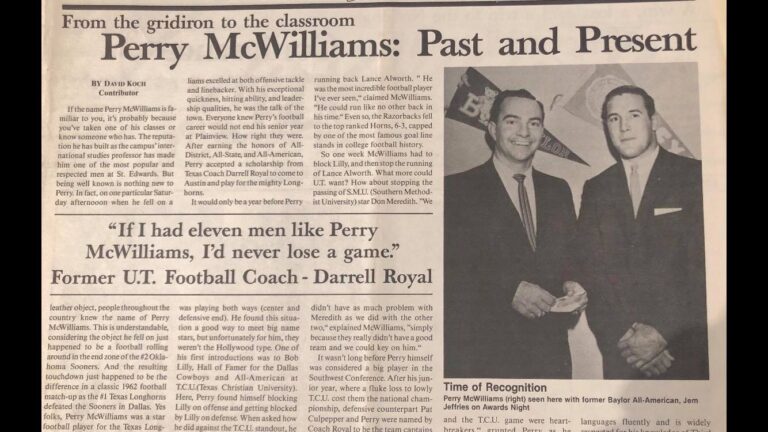

Bill Attesis

Billy – see attached paintings that were so graciously given to me by Anthony Rather who found them in a garage of a house that he had just purchased. He took the trouble to find and contact me and offer them to me. I then went on a mission to find a contact in the Lester clan to send Danny’s painting to. I researched his mother’s obit and found Shone Nix (a grandson), the Chief of Police in Pottsboro, Texas. I contacted Shone and he was tickled to hear from me and, in fact, had inherited all of Danny’s memorabilia. Such a great memory of such a special time in our lives.

Hook’em,

Bill Attesis

“When they had protest marches, sometimes we were out there harassing the hippies. Danny was probably a little more sympathetic to their cause. “

From Pat Kelly

Good story. Thanks for sharing. I do the same thing on remembering things by a jersey number. And I always know who wore the numbers 88 and 22…

FROM PAUL ROBICHAU- DANNY LESTER

Great story on Danny. I still miss him today. He was a great friend and an even better teammate.

Gennusa

I agree with you on the greatness- in every way- of Danny Lester. One hell of a good guy- But when he took jersey number 23, he had to uphold the greatness of that number , which he certainly did. Ragan Gennusa-23- is a hard fellow to follow-

Tommy Asaff

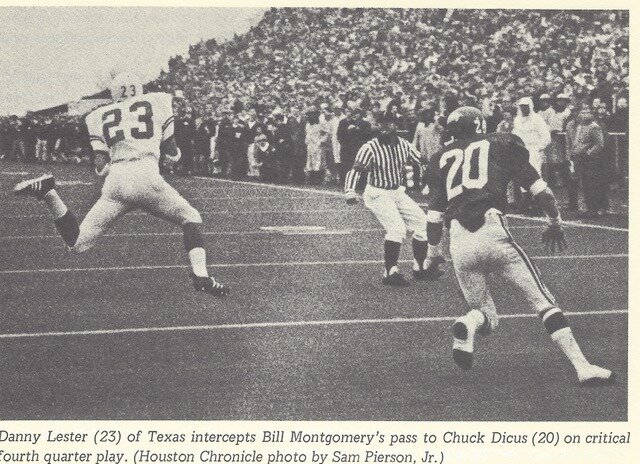

Danny made a crucial interception in the game against Arkansas in 1969 . He was a hell of a football player and even greater guy.

From Jerry Grider

What a really good testament to a very fine longhorn from a likewise good longhorn. “Lost but not forgotten” is a good thing to keep in practice. After all, our recall from our 20’s is much sharper than what we did last week.

From Bill Bradley

Danny and I were teammates at Texas and the Eagles of Philadelphia! He was a wonderful human being! Compassionate and decent! He never said a discouraging word about another teammate! A real friend and an even better teammate! I missed Danny and think about him often! RIP DANNY! BB

Glen Halsell

“Lester was a little bit sad and lonely. He was a deep person; some part of him looked like he had been hurt, and you didn’t want to violate it. There was a sincerity about him that kind of touched your heart.”

Fred Akers

“Danny was a tough-as-nails ranch kid. He was very quiet. I mean very quiet. After you got to know him, he was still quiet. But tough! Very, very tough.”

Steve Worster

“I had seen so much bullshit by then and so much plastic and so many groupies, and so many hangers-on, I appreciated that Danny was just such a real human being.”

Posted: Tuesday, September 07, 2004

Kevin Robbins

Austin American-Statesman

What will they say when they get around to Danny? What happens this weekend when they come to Danny’s part?

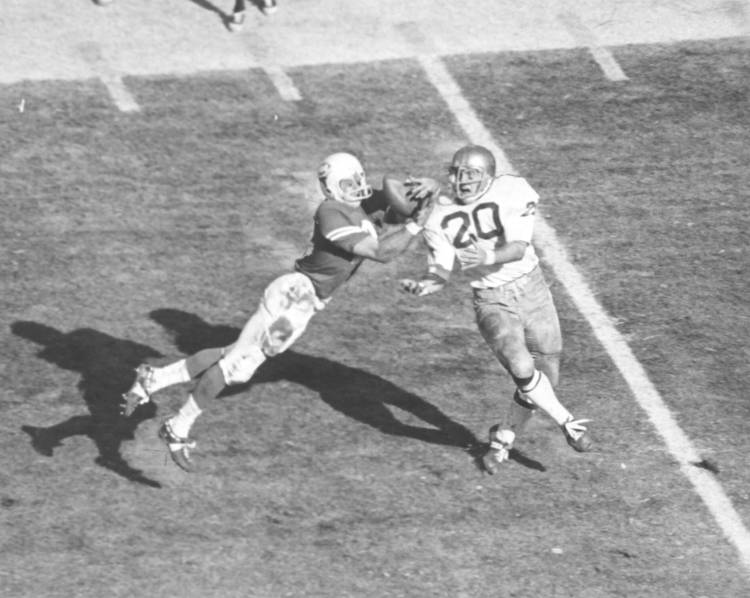

They’ll recall that it was third-and-goal from the Texas 7. That there were 10 minutes left in the ballgame. That the score was 14-8.

The men who were there will remember their disbelief, and maybe they’ll feel it again, because even after the fullness of 35 years, the play seems so reckless.

They’ll recollect that it was spitting rain the day that Danny Lester of Amarillo saved the 1969 national championship. If Danny himself were making the trip to Fayetteville, Ark., on Saturday for this year’s rekindling of an age-old rivalry, he’d explain to his old teammates and opponents how he was just doing what the coaches taught him to do.

Danny had a certain West Texas modesty. He never boasted much. Danny never said a whole lot at all. That was Danny, the old players will observe as they tell their stories about the Game of the Century.

They’re in their mid-50s now. Insurance men, real estate agents, entrepreneurs, lawyers, football coaches.

On Dec. 6, 1969, they were college football players for two undefeated teams in the Southwest Conference. Texas went into Razorback Stadium and melted the national championship hopes of Arkansas and its 44,000 rain-slickered fans.

The game has been chronicled in books, newspapers, magazine stories and pool-hall arguments from West Memphis to the edges of El Paso.

It’s the game that lives forever.

This weekend, many of those players will be back in Fayetteville, in body or in mind.

But Danny Lester is gone, buried in a country cemetery up in the town of Hereford.

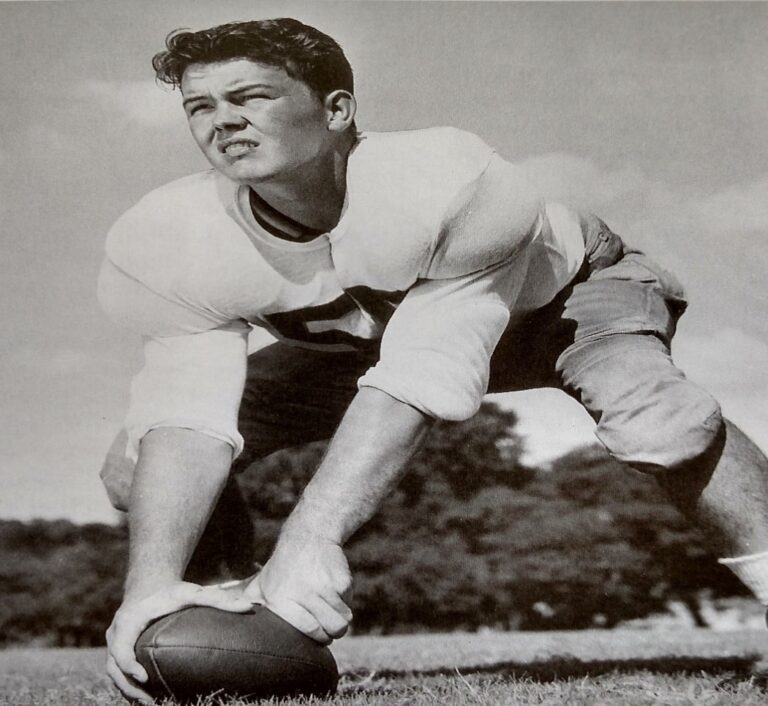

The nimble, quiet, dark-haired kid whose play enjoys everlasting life.

Who speaks for him?

The eyes that follow.

Danny Lester

The mother is on the telephone, walking through her house on Royal Road, telling what she sees.

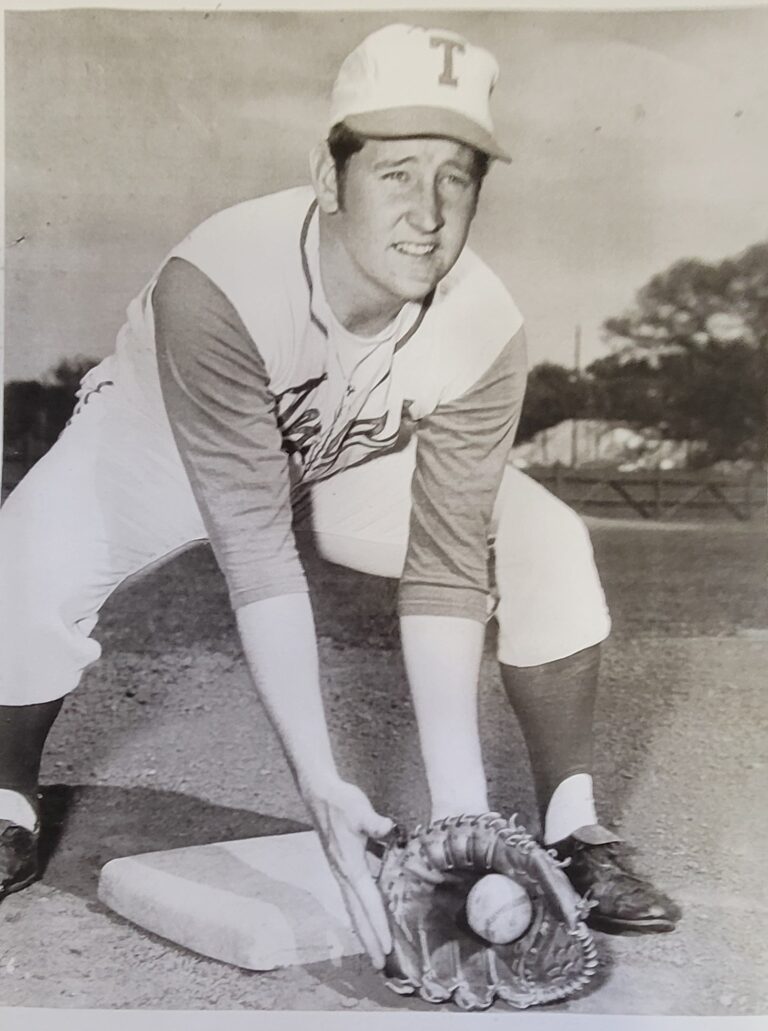

Kathleen Pulley still talks about her son in the present tense, not always, just now and again. Danny likes fishing in Alabama, where his people are from. Danny likes hunting quail and deer. Here’s a football from 1969, she says. The football team signed it, immortalizing the season. The ball now sits on a shelf in a small bedroom in Pulley’s home in Amarillo.

She sees an oil painting from the year before Danny died. She had it done when she was on a cruise ship in the Caribbean. She gave a photograph of Danny to a man doing portraits. Now it sits on that shelf with the footballs and the family pictures.

“It’s amazing what his eyes do to you,” Pulley says. “They follow you wherever you go.” Danny’s mother is 80, but her memories are fresh and vivid. She remembers how Danny liked the Boy Scouts, how he helped his friends by spreading feed for their cattle from a two-ton truck. She remembers how Danny was baptized properly in the church. She remembers how he liked to ride horses and go shopping and play cards, and she remembers how he especially loved to play football.

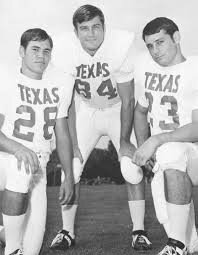

Danny chose UT as many Texas schoolboys did, but he could’ve worn any uniform in college football. Every school in the Southwest Conference recruited the 5-foot-11, 174-pound defensive back from Tascosa High School, the most feared team in the Panhandle. The Rebels went 31-4-1 the three seasons Danny wore their colors.

“He was one of the outstanding recruits in the state that year,” says Royal, who flew to Amarillo to sign Danny. “He was on everybody’s list.” Danny was on the Texas freshman team that lost no games. He played varsity beginning as a sophomore.Danny won the Blair Cherry award as Amarillo’s top college football player two straight years.

Royal used him at a receiver and defensive back. In 1970 after Cotton Speyer broke his arm, Danny played both ways and led the team in receptions.

Danny shared a room with Bud Hudgins, a defensive lineman. They and five other players bought Triumph 650 motorcycles their junior year and rode them out RM 2222 and RM 2244 when there were no mansions and strip malls, just cactus and canyons.

“We were just kids,” remembers Hudgins, now a developer in Fort Worth. “We were greener than short grass. But we were all about being a team and being together.”

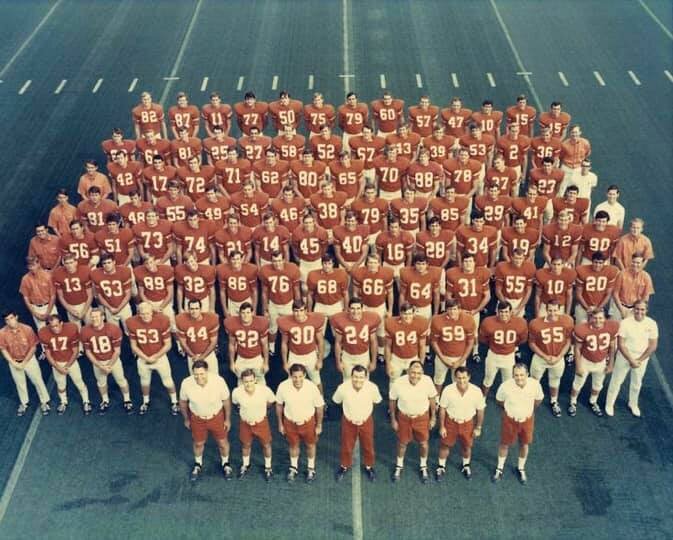

He and Danny were juniors in 1969, as Texas rode a winning streak that eventually spanned 30 games. By December, the Longhorns were still in the picture for the national title. The week before the Arkansas game stirred so much excitement in Austin that students couldn’t concentrate on school.

“Football was everything that week,” says Sharon Oxford. “It’s all we could think about … the game.” She and Danny were friends all four years of college. She was his Spook, the women who decorated players’ lockers before games. Now an anesthesiologist in Austin, she remains close with Danny’s mother, who comes to Austin at least once a year to go to a game with Oxford.

“When I walk into the stadium,” Oxford says, “I still feel Danny’s presence.”

She sat with the other Texas students that December day in Fayetteville. She always watched Danny every play of every game, so when Arkansas quarterback Bill Montgomery rolled left on third down and cocked to pass, “I knew he was in the right place.”

The play of his life.

Who expected it?

The Razorbacks had put the ball so deep in Texas territory they could touch the engraving on the Cotton Bowl trophy. They were up by six, early in the fourth quarter.

Had they simply run the ball on third-and-goal from the 7, as most every team in America did back then, the most they would’ve risked was a chance fumble. More likely they would’ve scored. A field goal. Even a touchdown.

Instead, Montgomery cocked and looked for Chuck Dicus, an All-American at split end.

On the Arkansas sideline, defensive end Bruce James watched Montgomery throw off of his back foot and thought, “Uh oh.” The ball floated.

“You could just see Danny breaking on the ball,” James said.

Danny stepped in front of Dicus, swallowed the pass, shook a tackler and loped out to the Texas 20 yard line.

Everyone stood. Fans sitting behind the Texas bench converged on Danny’s mother, whose seat was near midfield. The interception spun the momentum of the game so much so that Jerry Sisemore, a freshman offensive lineman watching on TV back in Austin, knew Texas was going to win.

“There were so many great plays,” recalls Sisemore, who played against Danny in high school.

“That one was like, This is it. This is going to happen today. Of the plays that swung the tide of battle, that might’ve been it.”

Texas won the game by a point.

They’ll talk a lot this weekend about James Street’s 42-yard touchdown run in the third quarter. They’ll talk plenty about the 53 veer pass that Royal called on fourth-and-3, and…….

They’ll recall that it was Jim Bertlesen who scored from two yards out for the touchdown, that it was Happy Feller who kicked the extra point, that it was Tom Campbell who made the late-game interception that sealed the 15-14 win in the presence of President Nixon and the college-football-loving nation.

But how will they describe what Danny did? How Danny gave them life?

“That was just his job,” his roommate Hudgins said. “He’d done it.”

The Longhorns went on to dispatch Notre Dame in the Cotton Bowl. There’s a picture in that bedroom in Pulley’s home of the Texas Tower, glowing No. 1. The players got Rolex watches. Danny already had one from the 1968 Cotton Bowl, so he gave his 1969 watch to his mother, who cried.

Danny kept his gold national championship ring, the one with diamonds in the numbers 1-9-6-9. He was wearing it the day he died.

The play was a part of him to the end. It’s his, forever. It’s everyone’s to celebrate, but no one else’s to claim.

Regrets and a loss

The mayor of Amarillo proclaimed Jan. 30, 1970, as Danny Lester Day. Danny won the first Blair Cherry Memorial Award given to the best college football player from Amarillo. The headline in the newspaper the next day said, “Danny Lester – Winner.”

The Philadelphia Eagles drafted Danny in the 13th round in 1971. He reported to camp at a small Methodist college in Reading, Pa., but got cut. The Eagles also drafted Bruce James, the Arkansas lineman who watched helplessly as Danny made the interception in 1969. But James blew a knee in camp.

Danny told James the NFL left him ambivalent, even disillusioned, about the sport. Professional football had none of the unity Danny loved at Texas. He missed the caring toughness of Royal.

Danny gave James a ride to the Philadelphia airport in his new yellow Porsche. Danny tried to persuade the old Razorback into going to Canada for a cross-country drive down the Pacific Coast. But James had a job waiting and no time to drive through the West in a new yellow Porsche.

“You know, I’ve regretted that, all these years,” says James, now an insurance agent in Little Rock.

Danny found work on an offshore oil rig in Louisiana. On Sept. 4, 1973, he and a friend from the rig had just passed Houston. They were on vacation. Danny was driving. They were going to Austin.

It was a Tuesday, 12 days before Danny would have turned 25 years old.

It was raining hard. Hurricane Delia was chewing through Texas. The winds were fierce as the friends made their way along Interstate 10.

A gust threw an eastbound tractor-trailer into their lane. The doors of the trailer were ripped away by the wind. Like sawblades, they sliced the truck Danny was driving in half. Danny and his friend died on the highway. His 1968 Cotton Bowl watch stopped at 4:15 p.m.

More than 1,500 people came to his funeral at the Paramount Baptist Church in Amarillo, where Danny had been baptized. Some in the pews had been to the funeral two years earlier for Freddie Steinmark, Danny’s teammate in the defensive backfield who died of cancer.

They had to scatter chairs in the vestibule to seat everyone who came to Danny’s service. There might’ve been more, but the remnants of Delia had made their way up the state, grounding the airplane in Austin that Royal and others from Texas were going to take. On the casket was a football bearing Danny’s number, 23.

It was raining the day they buried Danny Lester in the Panhandle dirt.

Kathleen Pulley still goes to Restlawn Cemetery on holidays and anniversaries. She finds the flat stone that bears her son’s name and places fresh flowers there.

“Nothing’s been on that grave but burnt orange and white,” Danny’s mother says.

She wore Danny’s ring for a long time. Then she locked it away.

She attended one of the reunions of the lettermen who played for Texas when there was no better football team in the land. She regrets that some of the men seemed hesitant to approach her, as if talking about her son might bring her pain. But it’s just the opposite, Pulley says. And now, when she visits with Danny’s teammates, they talk about Danny and smile.

She remembers something her son told her not long after the Game of the Century.

“I was the most fortunate person that ever was, to be at Texas at the right time, to be with that particular group of young men,” is what Danny said.

“It wasn’t just one player,” Pulley says. “They were a team.”

Who speaks now?

They all do.